It was surely intended as a paean to the dreams of public housing. There, on the walls of the community building lobby at Richard Allen Homes in Philadelphia, the artist had depicted what the New Deal planners had hoped life would be like in one of the first of the city’s public housing projects: a smiling mother, her baby in her arms, waving goodbye to her husband as he heads off to work, lunch box in hand; a woman sitting on the front steps reading a book while children play on the lawn with model airplanes and popguns; sleek youths in athletic uniforms, playing hard at baseball, football and basketball.

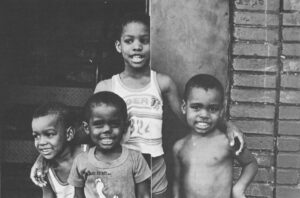

The mural has long ago faded. The paint has peeled off in huge chunks, leaving gaping holes in the human figures. What remains is a sadly ironic reminder of a dream that bears little resemblance to current life at Richard Allen Homes. These days, the only athletic facilities on the project’s grounds are the milk crates the kids have nailed to trees as makeshift hoops so they can play basketball on the cracked pavement. And mothers keep a vigilant eye on their young for fear they may get caught in the crossfire between drug dealers who frequently battle with real guns, not popguns.

The mural has long ago faded. The paint has peeled off in huge chunks, leaving gaping holes in the human figures. What remains is a sadly ironic reminder of a dream that bears little resemblance to current life at Richard Allen Homes. These days, the only athletic facilities on the project’s grounds are the milk crates the kids have nailed to trees as makeshift hoops so they can play basketball on the cracked pavement. And mothers keep a vigilant eye on their young for fear they may get caught in the crossfire between drug dealers who frequently battle with real guns, not popguns.

The fate of Richard Allen Homes is not unlike that of many of America’s public housing projects, especially those in the largest cities. Conceived during the Great Depression as a means of aiding the ailing construction industry and providing decent, low-rent housing for the families of unemployed blue-collar workers, the nation’s public housing program has burgeoned into a system that includes 1.2 million units housing more than 3.5 million people. This year the program will cost the federal government more than $4 billion for operating subsidies, construction debts and major repairs.

It is a system much of which was built three and four decades ago and that would be in need of major renovations even if it had been adequately maintained over the years, which it surely has not. It is a system that even its staunchest supporters admit has been plagued by mismanagement in some cities, often aggravated by local political interference and patronage. And it is a system that has become home to a permanent underclass of chronically unemployed and under-employed people who can ill afford to pay significantly more in rents to offset the skyrocketing cost of operations and maintenance.

Reagan Target

And, since Ronald Reagan took office in 1981, it is a system that has become a favorite target of the federal budget cutters’ ax. The Reagan Administration came to Washington vowing to get the government out of the business of building subsidized housing for the poor–a task the Administration, in its zeal for the free-enterprise system, maintains that government has woefully bungled and that can be better handled by the private sector. In the last 3 1/2 years under Reagan, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) has gone a long way toward achieving that goal. Not only has it opposed the authorization of any new federally-subsidized, low-income housing, but it has canceled the construction of more than half of the new units that had been authorized under previous administrations but had not yet been begun. Unless there is a change of administrations or the supporters of public housing in Congress force a dramatic change in policy, the construction of subsidized units for low-income people, begun under Franklin Roosevelt and continued under every succeeding president, will have virtually come to a halt by 1986.

But the advocates of public housing insist the Reagan Administration does not intend to stop there. The ultimate goal of this administration, these critics say, is to get the government out of the housing business, period. And, they contend, that means divesting the federal government of its responsibilities to the housing projects to the greatest extent possible, either by selling them to private developers or, in the case of those in the worst disrepair, demolishing them.

“It’s like a vanishing act,” said Gordon Cavanaugh, an attorney for the Council of Large Public Housing Authorities, an organization representing housing agencies in 34 cities across the country. “I don’t have any question in my mind that they (the Administration) are trying to keep cutting the program back and cutting it back until eventually they can get rid of it.”

In recent interviews, Administration officials denied those charges. Their immediate goal, they insisted, was to halt expansion and to maintain and upgrade the existing system, not eradicate it.

“We are not in the business of getting the government out of public housing,” said Warren T. Lindquist, HUD Assistant Secretary for Public and Indian Housing. “But with the billions and billions of dollars that have gone into public housing over the years, it hasn’t gotten better. It’s gotten worse…We’ve got to turn around our objectives.”

After looking at some of the horrid conditions afflicting the public housing system, the question arises: Is it worth saving? In cities like Detroit and Providence, RI, roughly one out of every four public housing units are vacant and have fallen prey to vandalism and neglect. In New Orleans, Newark, NJ, and other large cities, tenants tell of chronically vacant units that become hangouts for drug addicts and hoodlums, of apartments plagued with rats and roaches and hallways littered with trash and urine, of antiquated heating and plumbing systems that break down frequently and often go unrepaired for weeks or months. In Philadelphia and Camden, NJ, city inspectors say they routinely ignore safety violations in public housing projects because they know the housing authority will not make the necessary repairs and the tenants have no place else to go.

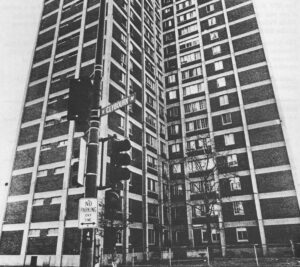

Roxanne Robinson, who has lived in Chicago’s Cabrini-Green Homes for the last nine years, knows all about how tough life can be in the worst of public housing.

For much of the past year, the elevators in her high-rise building have been out of service, so she and her three children have had to climb the stairs to their eighth-floor apartment. Just before last Christmas, when a bitter cold snap hit the Windy City, the pipes in her building burst, and the subsequent flooding knocked the heating system out of operation. It took several days before her landlord, the Chicago Housing Authority, made the necessary repairs. Less than a week later, the floor of her apartment was covered with water from busted pipes in the ceiling, and she and her children were huddling around the stove, trying to stay warm.

“It just doesn’t seem like it ought to take that much to make these projects livable,” Ms. Robinson said. “I just don’t think anybody really cares what happens in the projects.”

Yet, despite the problems, almost every housing authority has a waiting list of people eager to get into public housing. And even the system’s harshest critics acknowledge that the vast majority of the nation’s 2,800 local housing authorities, most of them located in small cities and towns, are well-run and are fulfilling their mandate to provide decent housing for the poor. HUD lists 21 housing authorities as “financially troubled,” nearly all of them in major cities, and Administration officials say about 100 others have serious problems in their management or housing conditions. But it is those authorities, where the largest number of tenants are concentrated, that have received the most attention from the press and from a public that historically has had little sympathy for public housing.

“It’s easy to beat up on the housing authorities that are in the major urban areas,” observed Robert E. McKay, executive director of the Council of Large Public Housing Authorities. “They’re doing a job that no one else in the city seems to want to do–and that is, housing the urban poor.”

To understand the current plight of public housing in America, one must go back to the beginning. The program had its origins in the Housing Act of 1937, a landmark piece of federal legislation that was never intended to serve the dire poor and that listed the provision of low-income housing only as a secondary purpose. The primary intent of the bill was to stimulate employment and help revive a stagnant construction industry devastated by the Depression. The government would enter into a long-term commitment with local housing authorities to finance construction costs; the authorities would be responsible for funding the operating expenses, primarily through rental income, and the residents would be working-class families, hard-pressed by hard times, who would reap the benefit of lower rents.

But by the 1960s, the picture of public housing had changed dramatically, just as it had in virtually all aspects of urban life. Many of the working-class families had moved out of the projects, often forced out by regulations that lowered the ceiling on residents’ maximum income. In their place came much poorer tenants, frequently black, single-parent families surviving on minimal wages or welfare. But while tenants were becoming less and less able to pay their own way, housing authorities were trying to cope with rising maintenance costs and mounting utility bills. As a result, needed repairs were deferred year after year, often until what had been routine maintenance work became a major renovation project.

The housing authorities’ already precarious financial position was exacerbated with the passage in 1969 of an amendment to the housing laws which limited the rent that could be charged to 25 percent of the tenant’s income. The legislation was intended to relieve a situation where some public housing residents were being forced to pay more than half their income for rent. But while aiding the poorest tenants, the new law reduced income revenue for the financially strapped housing authorities, which then turned to the federal government for help. The response was an influx of annual federal operating subsidies to local authorities, which has grown astronomically in the last 15 years. Between 1969 and 1971, these operating subsidies, which originally were never intended as part of the public housing program, rose from $12.6 million to $102.8 million. By 1984, they had ballooned to more than $1.2 billion.

With such staggering increases, it was not surprising that public housing was one of the costly social programs that the Reagan Administration came to Washington eager to cut.

In its first year in office, the Administration refused to seek additional funding to provide the full level of anticipated subsidies to local housing authorities. The authorities, some of which were faced with potential cuts of as much as 30 percent, filed a lawsuit, and eventually, after Congress initiated action on its own, most of the funding was restored. In subsequent years, largely due to additional appropriations by Congress, funding for major renovations in the public housing system has actually been increased. But even the most optimistic supporters of public housing do not expect the funding for repairs to reach the $6 billion to $10 billion that it is estimated would be needed to adequately rehabilitate the most severely blighted projects.

As an alternative to conventional public housing programs, the Reagan Administration is supporting a system under which low-income families would receive vouchers, the equivalent of Food Stamps for housing, which they could then use to find housing on the private market. The voucher subsidy would be for the difference between 30 percent of the family’s income and the fair market rent of a suitably-sized unit. Its advocates in the Administration argue that the voucher system would avoid the segregation and “warehousing” of the poor in housing projects and would allow low-income families to choose where they live–all at less cost than a new construction program.

The voucher system has been met with skepticism by Congress and by public housing advocates. For this budget year, Congress authorized less than 20 percent of the 87,00 vouchers being sought by the Administration. Critics of the program point to a shortage of decent, low-cost housing in the largest cities and question whether vouchers will provide real help to those most in need or whether they will simply encourage private landlords to increase rents because they know tenants have additional funds available. And since the vouchers are only authorized for five years, these critics say, they do not represent a long-term commitment to providing housing for the poor.

“Housing vouchers do nothing to stimulate new construction or to substantially improve the condition of occupied housing,” said Mary K. Nenno, associate director of the National Association of Housing and Redevelopment Officials. “The thing they do is help families already living in standard housing pay their rent.

“This Administration doesn’t believe in public ownership–that’s one, of their basic tenets,” Nenno added. “Many people, including myself, wonder if this (voucher system) will simply be used as a way to get the government out of public housing and then eventually cut off the vouchers.”

Disposing Of Housing

Under the Reagan Administration, HUD reports have cited the option of “disposing” of some housing projects, particularly those badly in need of repair and with large numbers of vacant units, either by demolishing them or selling them. In the case of the Washington Place project in Dallas, HUD has given its support to current plans to sell the 347-unit development to make way for the expansion of a local hospital.

HUD Under Secretary Philip Abrams said that while the Administration supports giving local authorities the option of selling or demolishing the most badly deteriorated projects, it has no intention of scrapping the existing public housing system, which is less expensive to maintain than any new construction or subsidy program. Much of the opposition to Administration policies, he contended, stemmed from resentment toward HUD’s efforts to improve management at the so-called “troubled” authorities.

“I don’t think public housing welcomes the amount of attention we’re giving them,” Abrams said, noting recent HUD audits and reports criticizing the operations of local housing authorities.

Obsessed With Failures

While not denying that serious problems exist in some cities, many public housing advocates say the Administration and the press have been so obsessed with the failures in the system, that they have ignored recent successes. Boston, for example, long considered one of the horror stories of public housing, has rehabilitated more than 1,300 vacant units and has turned a $2.3 million deficit into a $6.8 million reserve fund in the last four years. St. Louis, which became a national symbol of the public housing fiasco with the dynamiting of the infamous Pruitt-Igoe project in 1972, has since salvaged other problem-plagued projects by turning over the management to private and nonprofit groups, some of which are operated by the tenants themselves. Tenant management has also succeeded at the 464-unit Kenilworth-Parkside development in Washington, DC, where the rent collection rate has risen from a dismal 60 percent to better than 98 percent since a tenant-organized corporation, which trains and employs residents, took over two years ago.

“Sure, public housing has problems,” said James R. Alexander, executive director of the city housing authority in Mobile, Ala. “But you’ve got to remember, we’re housing the lowest-income, most deprived people in this country, people that private landlords just aren’t geared to providing any housing for.

“If there’s no real commitment to save public housing,” he added, “tell me, where are these people going to go?”

©1984 Roger Cohn

Roger Cohn, reporter on leave form the Philadelphia Inquirer, is investigating public housing in America.