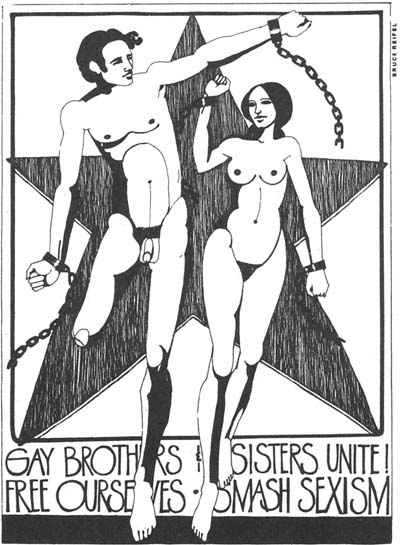

Note: One of the key issues in the debate over the psychological conditioning technology known as “behavior modification” is who should decide what behavior to modify, and on what basis. Critics of behavior modification say that when therapy reaches this point science dissolves into politics and the therapist becomes a coercive agent of the status quo. The following article illuminates this controversy as it applies to changing homosexuality to heterosexuality through “aversive” procedures involving electrical shocks. Until recently the only opposition to such goals and procedures came from militant gay organizations. Now, however, the issue has divided behavior modifiers within their own ranks.

San Francisco — The holidays were a busy time in Gay San Francisco. The city’s 80-some gay bars were preparing for a massive New Year’s Eve celebration to mark not only the advent of the Bicentennial Year but also the enactment of California’s new sex reform law. All private sex relations between consenting adults would become lawful at midnight.

Just a few months before, gay activists had won their long fight to persuade the Nomenclature Committee of the American Psychiatric Association to drop homosexuality from its catalog of mental disorders and issue a strong statement calling for an end to discrimination against gays. So this Yuletide gay Californians could anticipate being not only officially sane but officially legal — perfect gifts for men and women who might have everything.

Up on Nob Hill, there was little comfort or joy for Gerald Davison as he faced his audience in the Pavilion Room of the Fairmont Hotel. One year before, Davison had been elected president of the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy, the national organization of clinicians who practice behavior modification — psychological techniques derived from theories of reinforcement and operant conditioning. Davison had used the occasion of his inaugural address to issue a call for a complete halt to the use of behavior modification to “convert” homosexual men and women to heterosexuals.

Davison’s speech was unpopular, and all the more so because he could not be labeled a radical. Indeed, Davison had been the prime architect of “playboy therapy,” a method widely used to extinguish homosexual desires.

There are many variations of “playboy therapy,” but all of them are based on the idea of “aversive counterconditioning.” As opposed to positive reinforcement therapies, which attempt to change behavior by systematically rewarding desirable responses, aversive therapies use systematic punishment to suppress undesirable responses and build “aversions” or avoidance reactions, to stimuli which trigger the unwanted behavior.

Behavior modifiers dislike aversive methods because they create nothing new. Punishment only inhibits; it does not create new attractions. In a reward model, on the other hand, old habits die out naturally as new and more rewarding ones are implanted. The old is not beaten down; it is merely sloughed off.

But if the unwanted behavior is either highly rewarding — as in the case of deviant sex — or self-destructive — as in the case of autistic children who are mutilating themselves — behavior modifiers may find themselves powerless to compete with what is already going on. It is here that they resort to aversive methods. The first step in therapy is simply to bring things to a halt so that something else can happen. This is the stage at which one reads of cattle prods being used on autistic children, and “playboy therapy” being used on homosexual clients.

In “playboy therapy,” the client (usually a man) sits before a screen and views slides of attractive men, clothed and nude. He holds a switch which changes the slides, but the therapist has final control over the projector. While he watches the men, he receives an uncomfortable shock delivered through electrodes strapped to his legs. This shock is supposed to set up an unpleasant association with the sexual imagery before him.

After this association has been conditioned, he is given the opportunity to avoid the shock by changing the slide within a certain number of seconds. As he changes the slide, a picture of an attractive woman appears. Sometimes the picture of the woman will appear while the man is being shocked and then the shock stops. The idea is to develop an avoidance reaction to homosexual images and to make the man associate female images with relief. There are refinements to the procedure, but these are the basic features.

Davison had pioneered this therapy, and now he had renounced it. Not only that: he had declared that behavior therapists should refuse to help homosexual clients change their orientation even when they request it.

The controversy had not abated over a year, and now Davison was back to face his peers.

“I start with the premise that there’s no such thing as a neutral therapist,” Davison began. “The naturalness of what most of us agree to do with certain kinds of problems tends to blind us to the prejudices and biases that we exercise. I would suggest to you that our biases are most subtle, problematic, and insidious when we deal with people who are inclined to favor sexual contacts with members of the same sex.

“Now, you and I know that the rhetoric of behavior therapy holds that they’re just plain folks just like the rest of us and it’s all social learning. That may be so, but there is a troubling inconsistency in taking that view and then on the other hand being very ready — and eager, even — to change people’s sexual orientation.

If sexual preference per se is not supposed to be proof of a problem, he said, why is it that all the research and work in sexual adjustment goes in only one direction — from gay to straight?

“In other words, I think that what we do in research and the kind of clinical activity we engage in has to tell us something about where our values lie,” he said.

Davison asserted that the very fact of mental health professionals continuing to focus on converting homosexuals to heterosexuals “tends to validate the prejudice, tends to impede change, and tends to limit the options available to homosexuals.”

In addition, he said, “the availability of techniques encourages their use. So therefore I came to the conclusion after two or three years of agonizing and self-examination and reading and talking with students and just kind of reflecting on things, that we should stop offering therapy aimed at altering the choice of adult partners to whom our clients are attracted and stop giving treatment when people ask for it.”

Davison said that in the past year critics have accused him of practicing “coercive liberalism” by refusing to honor the wishes of clients who request sexual orientation change.

“It’s a very difficult position and it makes me very uncomfortable,” he confessed. “It’s very disquieting to me to say ‘no’ when somebody asks for help. But this is where I guess I’m getting mushy-headed as a behavior therapist because I guess I’m beginning to be skeptical of what people tell me. When people say, ‘This is what I want to change,’ I’m beginning to wonder.”

Everyone in American society is so indoctrinated to the view that same-sex relations are sick and undesirable that “to overlook, or to downplay, or to not take very seriously the coerciveness inherent in bearing a social stigma — to talk about people ‘voluntarily’ asking for change — is to be terribly naive and not to be good determinists, not to be good behaviorists, not even to be good scientists let alone good practitioners and good people,” he said.

Davison said he had reviewed all the literature on change-of-orientation therapy. “If you look very carefully at those data you will find that there are no cures,” he said. Follow-up studies on celebrated cases of “success” reveal that “they ended up in worse shape than before. The changes were ephemeral, they got themselves into heterosexual marriages — and a heterosexual marriage is a problematic situation as any clinician, anyone who’s alive and aware knows — and with all those problems plus the fact that they were still turned on and trying to suppress their urges, these people ended up in worse shape.”

Davison concluded that behavior therapy should address itself to problems common to clients of all sexual orientations, such as depression, irrational fears, low self-esteem, and sexual dysfunction, but leave the basic sexual preferences of people alone.

The Therapist as Sadist

Charles Silverstein, director of a New York-based gay counseling service called the Institute of Human Identity, took the position that therapists who offer sexual reorientation services are involving themselves in nothing less than a sado-masochistic drama.

“The people who present themselves as candidates for sexual orientation change are suffering from a number of severe problems,” he said. “As a rule, they are men — very rarely women — who have hidden their sexuality for many years. The years of loneliness and personal alienation have filled them with guilt about their sexual desires.

“They feel guilty about so many things. They have disappointed their parents by not having children. They have disappointed their fathers by not being the man he wanted his son to be. They have disappointed wives who do not understand the special secret or the reason for marital distance.”

But most disturbing, he said, is the fact that they are not angry. You would expect such men to be angry at a society and family structure which frustrates them and “defines their potential happiness as sin, social malady, or mental disorder;” yet they are not, he said.

“Our closeted patient has accepted the pejorative labels as true and, like the society around him, defines himself as a sinner. The patient asking for sexual orientation change perceives himself as guilty as charged, and his hidden agenda in therapy is punishment for his sin. He receives his therapist as an agent of society who will punish his wickedness appropriately.”

Therapy for sexual reorientation in present-day America is sado-masochistic theater, Silverstein asserted, “with the guilt-ridden homosexual playing the part of the humiliated and the therapist playing the role of the sadist punishing him for transgressing the rules.”

Aversion therapy, which subjects the client to electrical shocks while he contemplates the forbidden objects of his desire, is “violence in the name of science,” Silverstein said. “As long as therapeutic procedure is defined by attitudes of guilt and punishment, therapy will be a failure.”

The real problem, according to Silverstein, has little to do with sexual behavior but everything to do with rigidly enforced sex roles.

“To act unlike a man is to act more like a woman,” according to these rigid roles, “and therein lies the problem for our homosexual man. The request for sexual orientation change is an expression of fear that he has lost his manliness and become more like a woman. He fears the female status because it is lower than his own, and he indicates his contempt for women by fearing to become one.”

And the diagnosis?

“Our patient suffers deeply from his depression, from his deep-seated loss of self-esteem, from a rigid adherence to norms of gender-appropriate behavior, from a contempt for women, from a masochistic desire to be punished for his transgression of the proper masculine role, and from a very confused idea of masculinity and femininity,” Silverstein said.

“He does not suffer from homosexuality.”

As for the behavior modifier, Silverstein said, “I can see no way out of the logical assumption that the therapist is just as confused about issues of masculinity and femininity and would be just as depressed as the patient if he thought he were homosexual.

“The only important difference between them is that the therapist acts from a position of power, whereas the patient acts from a position of weakness.”

“Happy in the Head”

David Begelman, a bearded, burly professor from Kirkland College in Clinton, N.Y., attacked the thinking that behavior modifiers use to define homosexuality as a “problem behavior.”

You would think that if such an animal as the “problem behavior of homosexuality” existed, there would be an analogous “problem behavior of heterosexuality.” Yet there is not, he said.

“Just why do heterosexual clients come off no worse than having problems like ‘frigidity’ or ‘impotence’ but nothing as portentious as a ‘behavior disorder of heterosexuality,’ their occasional anguish notwithstanding?” he asked.

The reason, he said, is that the socially accepted standard of sexual adjustment is heterosexuality itself. Since heterosexuality is the standard, and not some independent measure of adjustment on which heterosexuals might outperform homosexuals, it is logically impossible for heterosexuals to be described as suffering from heterosexuality.

By the same logic, homosexuality has been classed as a disorder because “it is a significant departure from accepted standards of conduct, pure and simple,” he said. “Psychological inquiry has nothing to do with it.”

When psychological inquiry is made, Begelman said, well-adjusted homosexuals consistently show no difference in psychological functioning from well-adjusted heterosexuals. Thus the categorization of homosexuality as a special problem “is a sheer sociological creation.”

Many behavior modifiers defend sexual reorientation therapy with the argument that patients come to them troubled specifically about their homosexuality.

“Being ‘troubled,’ whatever that means, is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for defining a pattern as a disorder or maladaptive,” Begelman said. There are countless people living disordered and maladaptive lives who feel no anxiety about it at all, he said, and on the other hand there are countless people who are filled with guilt but whom no therapist would consider disordered.

Sometimes even the absence of guilt can be evidence of a disorder, Begelman said — for example, with war criminals like Lt. William Calley and Rudolf Hess, the Nazi commandant of Auschwitz.

What if a war criminal does feel guilty and comes to a behavior modifier for help?

“Undoubtedly, a heavy burden of subjective guilt can be lifted, modified,” said Begelman, “but the central question is: Ought it to be modified?”

“The notion that the ultimate criterion for behavioral intervention is to make clients ‘happy in the head’ is, in my judgment, a disastrous moral legacy,” he said. “I should have thought that the aim of any significant enterprise, therapeutic or otherwise, is to do what is right — not to make someone happy.”

Begelman took the position that the therapist cannot use either social whims or the wishes of clients as easy formulas for deciding what is proper in therapy.

If you use the guideline of clients’ wishes, how could you refuse someone’s request to be turned into a vegetable by lobotomy? he said. “The example is outlandish, surely, yet it establishes firmly the point that a client’s wishes cannot constitute a workable, exhaustive criterion of a behavioral goal.”

If you use the guideline of social tastes, you run into other problems, he said. For example, “generation-gap phenomena often consist in a youngster’s coming to believe he has a problem at his parents’ instigation.”

“I don’t see why dropping out, wearing long hair, and playing Elton John records continually are necessarily signs of a grave psychiatric condition.” Yet some parents do, and therapists are challenged to honor their values, he said.

For another example, “I see no reason, as Carl Gustav Jung once did, to provide treatment for a woman whose interest in graduate studies in mathematics had her convinced in that particular Victorian era that she exhibited ‘pathological masculine tendencies.”‘

“It’s interesting, isn’t it, how all normally equilibrated psyches just happen to coincide with external behaviors stamped ‘Approved’ by our ubiquitous friend out there, Society.” Begelman said.

Tweaking his audience slightly, Begelman suggested that behavior modifiers should be the last people to worship social convention since their own persuasion runs heavily against conventional wisdom about free will and the causes of behavior. The fact that they stick to their guns in the face of heavy attack “indicates that perhaps you are not so impressed with what is socially acceptable, despite what you say in those textbooks on abnormal psychology,” he said.

Begelman concluded that behavior therapists should withstand social pressure as strongly with their clients as they do for themselves. He urged the audience to cease sexual reorientation therapy.

“To administer these programs is to further reinforce the prevailing belief system about homosexuality,” he said. “The meaning of the act of providing reorientation services is another element in a causal nexus of oppression.”

“I am not recommending that we desert clients in distress,” he added, “I am recommending that we work with them in every way short of sexual reorientation.”

Backlash

The audience at the Fairmont had not been modified.

A man stood up. Given all the bias against homosexuals, he said, isn’t it cruel to rule out therapy absolutely? “Aren’t you robbing the client of the dignity of making the decision?” he asked. “Aren’t you jumping back as quickly as you can into a dynamic model where the therapist defines what the problem is, what the appropriate solution is, and what the appropriate language is?”

There was loud applause. Davison replied:

“At Stony Brook where I work and train students, the trend at the clinic has been very much away from people seeking reorientation to heterosexuality in the last five years. I think we have to ask why. If it is generally the case, I would suggest that the growing militancy of homosexual groups has something to do with it and the growing acceptance of homosexuality and lessening of legal pressures against homosexuality has something to do with it. I suspect that when the social pressures that have existed diminish, and it will certainly take some time, there will be fewer and fewer people who will define themselves as having that problem.”

Until that day, Davison said, “continuing to act as if people are able after a few sessions to say, ‘Yes, I want to change,’ and then going ahead, is retrogressive and condones the societal pressure, I believe.”

The questioner persisted.

“Don’t we face a situation where we might say, ‘Well, let’s not do dentistry because the drilling of cavities is sadism in the name of science?’ Or take marriage counseling. There’s no question that society and therapists have a preference for relationships that have the sacrament of marriage. Shall we stop counseling people to stay together because of our ‘irrational’ bias in favor of marriage?”

“Or, why not stop dealing with psychotics? The problem is mostly that society can’t handle deviant behavior. I say sure, work with society — but why relegate somebody to a life of pain because of what’s going on around them?”

Silverstein replied:

“I hear the same liberal attitude that is used to oppress any out-group — that we’re a group of healers, and we’re going to respond to this person’s pain.

“What I’m suggesting is that you’re going to have a person who’s going to have more pain because of what you do. When we tell people they’re going to get better if they take this treatment, we’re lying to them. A large percentage of them are going to be unadaptive.

“As a matter of fact, people have been treated much better by therapists who suggested that they get in touch with other gay people. Sufficient role-modeling by other gay people can be a much quicker cure for some of their problems than any other kind of treatment.”

Of Fruits and Vegetables

Another therapist rose. “Listen, society puts trips on people other than being straight,” he said. “One of them is being achievers. I’m sure everybody here knows something about that or we wouldn’t have the degrees we do. It certainly is a societal trip.”

“But if somebody came to you and said, ‘I’m having trouble in school, I’d like to function more effectively, I’d like to change from being a poor student to being a good student,’ would you really question the need to change society rather than offering help?”

(“That’s right,” a woman in the audience said.)

“The degree to which I would or would not go along with it would reflect the bias that I would hold,” Davison replied. “Which is precisely the point I am trying to make.”

Silverstein added: “The reason I find this problem so fascinating is that it kind of flaps between two extremes. If someone came to you with a phobia and wanted treatment for that kind of thing, I think there would be little basis for raising a moral issue about whether the phobia should be treated. I think there’s a consensus on that.”

“I think there would also be consensus that we would not provide the modalities for someone who came to us and wanted to become a vegetable.”

“In the middle of these two extremes there are discussions about homosexuality. I believe that these discussions in 10 or 15 years will move in the direction of the kind of attitude we take toward turning people into vegetables. That is, there will be a value consensus on that.

“Part of the reason we’re taking the position we are taking here, which is a moral one, is to move things in the direction that homosexuality will be viewed on the model of what we would all do with respect to changing someone into a carrot.”

“Are you saying that being straight is like being a vegetable?” someone called out.

Silverstein just smiled.

Received in New York on February 19, 1976.

©1976 Ron McCrea

Ron McCrea is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Capital Times (Madison, Wisconsin). This article may be Published with credit to Mr. McCrea, The Capital Times, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation. The views expressed by the author in this newsletter are not necessarily the views of the Foundation.