Sri Tirtha Mahanta, the 74-year-old spiritual leader of the Bor Alengi Satra, a Hindu monastery on Majuli Island, in Assam’s Brahmaputra River, remembers the moment in 1950 when the island’s destiny changed forever. “I was in boarding school, eating my dinner. Suddenly the house started shaking like it was made of grass. All the ground was shaking. Then the land split open and muddy water came pouring out of the ground. Everyone started screaming and I got very scared. All the students were taken to a shop where we spent the night, sleeping on the floor. There were aftershocks all night. In the morning, there were dead bodies floating by in the river. Huge trees and wild animals washed up on the island. After that, the river was never the same. I think it went mad.”

Ever since, the Brahmaputra has been acting like a river with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, taking out much of its anxiety on Majuli Island, which is the largest freshwater river island in the world, a fifty-mile-long, pollution-free sanctuary of satras, primitive villages, and rice paddies. Majuli once comprised 400 square miles, but it is now only one-third that size, and the remainder is going fast.

For centuries, Majuli has been the spiritual center of Assam, a subtropical state in India’s northeastern corner, between Tibet and Myanmar, that is comprised primarily of the vast Brahmaputra River floodplain. Five hundred years ago, the Hindu saint Sankardeva introduced Majuli to Vaishnavism, a monotheistic form of Hinduism that emphasizes the use of prayer, dance, and ritualistic performances to attain awareness of God and eternal peace. By the time of the 1950 Assam earthquake, 65 Vaishnavite monasteries, known as satras, occupied the island, some holding more than 400 monks. In addition to prayers and contemplation, many satras developed a specialized craft. The monks of Samaguri Satra make elaborate masks used all over Assam for reenactments of scenes from the Mahabarata, Ramayana, and other sacred texts during festivals. The monks of Kamalabari Satra build fine wooden boats. And the monks of Benegenaati Satra teach sacred dance to pilgrims from all over India.

The 1950 Assam earthquake caused landslides throughout the uplands, liquidating entire hills. The river turned black and sulfurous for days as all that dirt washed downstream, settling in the river channel, raising it by six or seven feet in places, and forming giant sandbars that deflected the force of the now-raised river toward Majuli’s southern bank. And the deranged river began to gnaw on the edges of the island.

Today, Majuli in the dry season seems as peaceful as ever. Satras and villages mingle harmoniously in the raised areas, surrounded by a sea-like expanse of rice paddy. The islanders practice de facto organic agriculture, because they can’t afford pesticides. Mornings are filled with the sounds of chanting, drums, and cymbals. In some of the satras, the prayer rituals have been continuously performed, day and night, for more than 350 years. Reachable only by a small passenger ferry twice per day, Majuli remains an island of sandy bicycle paths overhung with bougainvillea and hibiscus trees, of world-class bird life, of tribal villages with bamboo houses raised on stilts, of open-air markets where men sell live river fish by candlelight as the inky evenings descend, and of nights so suffocatingly black and quiet that it feels as if a gigantic iron pot has been lowered over the place. The few tourists who find Majuli whisper conspiratorially when they cross paths: How do we keep it quiet? Yet that is hardly the concern. True, the Indian government has nominated the island and its culture for UNESCO World Heritage status, which will raise Majuli’s profile, but the honor may have to be awarded posthumously. Before the backpacking hordes discover Majuli, the island may have ceased to exist. Barring some dramatic intervention, Majuli and its ancient culture will disappear in a few decades. “The erosion is getting faster,” says Dulal Debnath, Circle Officer for Majuli Subdistrict. “If it is not prevented somehow, then after 50 years …” he shrugs fatalistically.

Every year during the summer monsoons, the Brahmaputra rises spectacularly, and huge chunks of Majuli wash away. The old road to the ferry dock ends in a crumbling sandy cliff. Barely visible on the horizon three miles away are the trees that mark the ridge where the dock used to be. Everything in between has been turned to river and sandbar. The ferry dock has been moved downstream, but every year it has to be relocated. Trees lean precipitously over Majuli’s fifteen-foot-high undercut bank, their exposed roots dangling in the air. At least 5,000 acres disappeared in 2011. When floodwaters began to excavate the footing of the tower that carries electrical lines to Majuli, islanders rallied and managed to pack enough sandbags to keep the tower upright, but it is sure to go in this year’s flood.

Of the 65 satras that once graced the island, 44 have washed away. Hem Chandra Goswami, third-generation master of Samaguri, the maskmaking satra, displays snapshots of priceless masks swept away during the 2007 floods. In Salmara, a village on the edge of the island that has been making pottery using a special river clay and driftwood-fired kilns, in a technique unchanged since the Bronze-Age Harappan civilization, the riverbank where the people dig their clay is so undermined that the government has told the villagers to leave the island and learn to make terra cotta pots somewhere else. Dozens of villages have washed away entirely, and now more and more of Majuli’s 150,000 residents live in ramshackle huts along the elevated roadsides. Nearly 10,000 families have been displaced since the 1960s; those who haven’t taken refuge on Majuli’s roadsides have left the island to join India’s great mass of impoverished migrant laborers. Islanders are grappling with new legal conundrums such as: If the land beneath your house melts into the river and reforms a mile downstream as a sandbar, is it still your land?

Although the effects of the 1950 earthquake were beyond anyone’s control, humans have exacerbated Majuli’s problems. Deforestation in the hills has removed the trees that used to hold the banks of the Brahmaputra’s tributaries in place, allowing too much sediment to wash downstream, where it acts like a sandblaster. And miles of levees upriver, designed to protect fields and villages from the annual floods, prevent the floodwaters from spreading out and dissipating, ensuring that the river hits Majuli with unnatural force. One-hundred-year floods have become every-year floods. And over everything hangs the specter of climate change, which scientists believe is intensifying the monsoons, concentrating the year’s rains into a shorter and more destructive window.

In 1996, the government of Assam tasked the Brahmaputra Board with halting the erosion of Majuli and other river communities. But fifteen years and $10 million later, there is no sign of progress. The edges of the island bristle with concrete “porcupines”—rows of giant spars, resembling the backbone of some sea monster, that sit along the riverbanks and are intended to induce siltation by slowing the flow of the water, thus rebuilding the banks—but in many places the porcupines seem to be having the opposite effect: banks are viciously eroded, and the porcupines themselves are collapsing into the river.

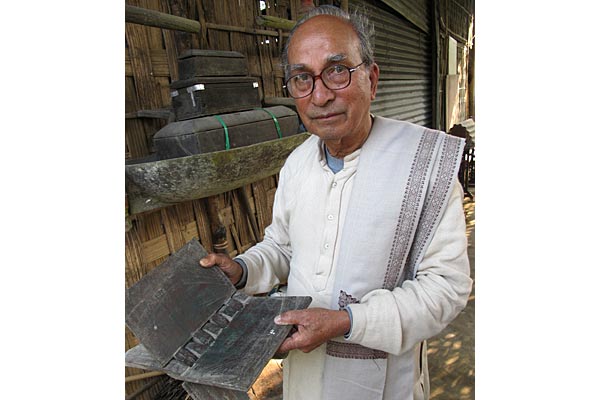

The latest victim of the river was Bor Alengi Satra, Sri Mahanta’s monastery. Unlike many of the satras, which are peopled by male, celibate monks, Bor Alengi was more like a church; the villagers who live around the prayer hall would attend morning and evening prayers each day, led by Sri Mahanta, and followers from all over Assam would show up for holiday services. So it had been for 176 years, all under the tutelage of Sri Mahanta and his ancestors. But on June 6, 2011, that all came to an end. That June the monsoons were well underway, and the water level had been rising dangerously. “But the morning of June 3,” Sri Mahanta says, “it began to drop, and we breathed a sigh of relief. Then all of a sudden, that afternoon, it reversed course and began to rise very fast. For two days it rose.” As the water began to carve away the land beneath the village, Sri Mahanta and the villagers worked desperately to salvage what they could. “We barely had time to rescue our holy books, offering plates, and other relics before the river took the entire prayer hall.” By June 6, the entire village was gone. The beautiful promontory where the satra had stood is now the Brahmaputra River. The only remaining signs of Bor Alengi are a cement well sticking out of the crumbling riverbank and the cement footing of a squat toilet. “I just cried,” Sri Mahanta says. “I couldn’t eat for a month, I was so heartbroken.”

Today Sri Mahanta and his wife stay one village inland in a temporary dwelling constructed of tin roofing panels, where he leads daily prayer service for his followers, who have settled wherever possible in the village. He has asked the government to find them some land on the mainland to rebuild. “For a monastery, it has to be the right place,” he says. “It has to be somewhere peaceful.” Yet, in a country with 1.2 billion people, which will soon surpass China as the world’s most populous, the kind of peace Majuli has known for 500 years may be a thing of the past.