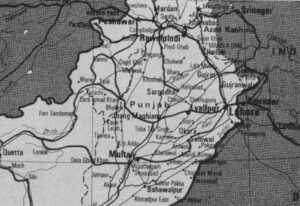

If any one place deserves to be called the birthplace of modern irrigation, that place is the Punjab, a sandy triangle of pancake-flat alluvium where India’s British rulers built the first of their 46 “canal colonies” in 1849.

The first colony consisted of only a few thousand Sikh soldiers dispossessed by the British invaders. But today, half a century after India’s four western provinces–including most of the Punjab–were torn off by fleeing colonialists and transformed into what is now Pakistan, 100 million people are coaxing sustenance out of the man-watered soils of the Indus River basin.

The first colony consisted of only a few thousand Sikh soldiers dispossessed by the British invaders. But today, half a century after India’s four western provinces–including most of the Punjab–were torn off by fleeing colonialists and transformed into what is now Pakistan, 100 million people are coaxing sustenance out of the man-watered soils of the Indus River basin.

No other nation has so many people who are so utterly dependent on artificial rain; four-fifths of Pakistan’s food comes from the irrigated Indus plains.

No other nation has more to lose if its farms are poisoned by the inevitable build up of natural salts from irrigation, and no other nation is trying harder to avoid that fate. Heroic drainage projects area tradition in Pakistan, and since the early 1950s, a dozen developed nations have sent plane loads of cash and advisers to lend a hand.

But the technological fixes that work in places like California aren’t working in the Punjab. Despite the foreign aid, from 15 to 20 percent of Pakistan’s irrigated farmland is too salted out or too water logged to grow a decent crop. Perhaps another 50 to 60 percent has a water-table within 10 feet of the surface and therefore is in serious peril.

The foreign experts know perfectly well how to do battle with the forces of nature. But in Pakistan, the enemy is more likely to be culture, politics, poverty, language, ignorance or fear.

Pakistan is a Babel of a nation; its 100 million inhabitants speak at least two dozen languages, and the simplest of communications can be a nightmare.

The two official languages are Urdu and English, but neither one is native. Few of the country’s peasants speak either of the “official” languages, so it was a surprise when two Americans heard a shouted “hello, hello” as they walked toward a Punjabi farmer near the little mud-brick village of Satiana, southeast of Faisalabad in the central Punjab.

The gregarious farmer was sitting under a tree; he had been taking turns with his brother plowing a half-acre of brown-gray earth. As the visitors approached he leapt to his feet and ran toward them, grinning broadly, his clothes flapping in the breeze.

I am farmer. This is my land,” the wiry peasant said, punctuating his speech with a proprietary sweep of his arm toward the tiny field. ‘I am farmer” wore the national costume of Pakistan, the shalwar kameez–a pair of light, baggy cotton trousers topped by a knee-length shirt. He had sandals on his feet. When he shook his visitors’ hands, the calluses were thick and as hard as the bark on a tree.

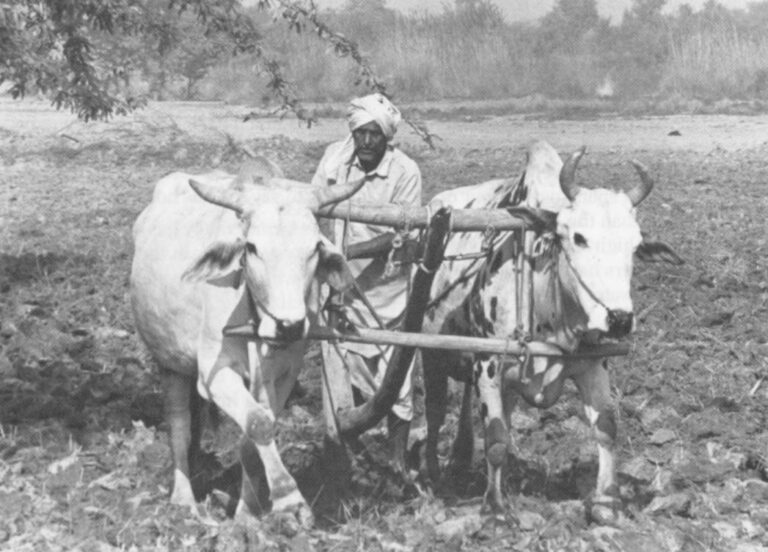

With one glance at the plow the brothers were using the reason for the calluses became clear. To call it a plow is to use the word recklessly; it was really just a few thick timbers lashed together and pulled by a pair of scrawny bullocks. Where that crude apparatus met the ground there was a heavy, pointed piece of steel–not a blade, but just a point. That plow was the state of the agricultural art in the rural Punjab, but unlike a conventional moldboard plow, it was not capable of turning over the earth; it merely gouged it and broke it up.

Before sowing their seeds, the brothers would spend days following their team back and forth across the field, wrestling that medieval tool into the ground until either they or the underfed animals dropped from exhaustion. Then, after they had turned the ground into a minefield of clods the size of basketballs, they would hitch their beasts to a huge, flattened timber and start dragging that around to pulverize the clods. Only after several days of this horribly brutal labor were the brothers ready to broadcast their seeds–they were planting wheat–and start irrigating.

A jarring contrast is apparent here, a contrast that lies at the very heart of the trouble in the Indus basin. The farmers of Pakistan are working their fields with Iron Age tools, but they are also served by one of the most technologically advanced systems ever devised for delivering water to the land. It is as though America’s interstate highways carried nothing more sophisticated than mule trains, except that in Pakistan, nobody seems to think twice about the contrast.

When the British brought irrigation to the Punjab in the mid-19th century, they built the first modern irrigation system in the world on what was previously just a bleak, arid plain overrun by bandits. With a huge infusion of foreign aid after it became independent, Pakistan expanded the British system. Today the nation owns two of the largest earthen dams ever built–Tarbela and Mangla–and its canals and diversion weirs are technological marvels.

But the system is imperfect. For one thing, it is chronically short of water. Bountiful as it is, the Indus River system simply doesn’t carry enough water to irrigate all of the land served by the system’s canals, so it’s not unusual for a farmer to find that his canal has run dry just as his crops have started to wilt in the 115-degree summer heat. When that happens, severe under-watering results, and the salt that ought to be washed downward by irrigation gets trapped instead in the surface soil, where it can poison crops.

To make matters worse, the system is also schizophrenic. Once the water reaches the mogha–the local term for a canal turnout that serves a cluster of small farms called a chak–the irrigation system changes abruptly from modern to primitive. The government steps aside, the farmers take over, and often they end up not under-watering but over-watering. They know that the canal may be dry the next time they need water, so when water is available, they give their crops far more water than they need, even though the excess simply seeps downward past the roots and is lost to the water table. Most of the world’s irrigated farmland is either under-watered or over-watered; Pakistan’s unfortunate distinction is that it is managing to be both at the same time.

The rudimentary tools used by the farmers only aggravate the problem. As water leaves the mogha, the farmers steer it into a shallow, weedy, leaky hand-dug ditch called a watercourse, and 22 percent of it immediately seeps into the ground. Then, the farmers irrigate their fields in the most wasteful way possible; they simply let the water flood over the land until everything is soaked. Since they don’t have real plows, they couldn’t create furrows if they wanted to, and since they don’t have any kind of grading equipment they can’t level their fields either. The high spots may be four or five inches higher than the low spots, so to make sure the high spots get enough water, the farmers have to give the low spots far more water than they need.

Pakistan certainly isn’t alone among nations in practicing Iron Age agriculture, but it is one of the few where such an ancient system of farming is served by such a modern water delivery system. While the government engineers work on computers in air-conditioned offices, the peasants work their fields with bullocks or water buffalo and haul their produce to town on donkey carts. They are not ignorant, but they are by and large illiterate, and their own government speaks to them indifferently, in a language that most of them cannot even understand.

They have too little water to start with, but for lack of better equipment and training, they waste much of what they have. Salt builds up in the soil where they under irrigate, and it builds up in the groundwater where they over irrigate, until the water table reaches the surface and brings the salt back up. The result is as frightening as it is inevitable: Beneath the feet of the peasants, the fertile ground of the Indus basin is slowly becoming a desert once again.

Pakistan inherited more from the British than just a common language and the custom of driving on the left. It also inherited a style of government, and more to the point, an attitude about the proper relationship between a government and its subjects–distant. If they wanted something done, the British just issued orders to their armies of native civil servants, whose loyalty was beyond question because their livelihood depended utterly on the British largesse.

In that sense, at least, nothing much has changed since partition. The English faces have been replaced by Muslim ones, but the imperial style remains intact. The average Punjabi farmer has about as much chance of impressing his views upon the provincial assembly as he has of getting an audience with the pope; that is to say, he has no chance at all.

“The farmer really has very little to say in our system. He’s at the mercy of the people who run the system,” admitted Mohammad Badruddin, who was chief of a section of WAPDA, Pakistan’s chief water development agency, until he went to work for the International Irrigation Management Institute in Lahore.

In Badruddin’s opinion, the fact that Pakistan’s farmers are so divorced from their government explains a lot about the trouble Pakistan is having with its irrigation system. From the giant storage reservoirs far upstream on the Indus and Chenab, to the comparative trickle of water that ripples through the moghas and into the watercourses, Pakistani irrigation is a government operation all the way–top-heavy, centralized, bureaucratic in the extreme, and utterly unresponsive to the wishes of the peasants whose interests it is supposed to be serving.

In the United States, irrigation farmers are typically organized into districts, which either own the water outright or sign contracts for government water and then arrange for its distribution; at their best–admittedly an infrequent state of affairs–the districts are effective lobbyists for the farmers and, simultaneously, effective policemen for the government.

No such beast exists in Pakistan; in fact, until 1979, even the mere act of organizing an association of water users was illegal. By most accounts the government was terrified of what would happen if the downtrodden peasants–who represent 70 percent of Pakistan’s population–ever found a political voice, so it did its best to stifle them.

Still, the government’s monopoly on power might not be so bad if it were complete, which it isn’t. Pakistan’s bureaucrats have traditionally seen their job as being limited to developing water and delivering it, and once they move the water to the mogha, they walk away from it.

In the resulting vacuum of leadership, farmers merely make up their own rules. They stretch their limited supplies of canal water as far as they dare, and then supplement them where possible with well water. Since precise applications of water are pretty much impossible in bullock-team agriculture, the farmers simply slop the water around by guesswork. Crops dry up, the soil gets salted out, and whatever excess water is occasionally applied just seeps downward and accumulates until it builds up to the surface and destroys the land.

But things may be changing now, out of necessity if nothing else. In the 1960s and 1970s, Pakistan drilled thousands of deep wells in hopes of lowering the water table in waterlogged areas and using the well water on crops in under-irrigated areas. The wells failed to make a significant dent in Pakistan’s problems, but soon the government noticed that farmers were scraping together the money to drill wells of their own, simply to use the extra water on their fields. That led, in some cases, to more over-watering, but it also gave some government officials an idea. If the farmers of the Punjab were capable of organizing themselves to drill a well–no simple task–then what else might they be able to accomplish? Maybe the way to solve the twinned problems of water-logging and salinity was not to improve the physical structures in isolation, but to improve the farmers, help them modernize their farming practices and move from the Iron Age into the 20th century.

Mohammad Munir Chaudry oversees a section of WAPDA that runs a pair of agricultural research stations where the government, for the first time in anyone’s memory, is working directly with farmers to change the way they put water on their land. Groups of farmers are being organized to rebuild their own watercourses–filling in the old buffalo wallows and other wide spots that allow water to seep into the ground. Munir said that 12,000 watercourses have already been rebuilt; that leaves another 78,000 to go. Farmers provide the labor; the government provides the materials; and once the work is finished, the government hopes that the farmers will catch on and start maintaining the watercourses themselves, just as they have built and maintained their own wells.

“We did not particularly involve the farmer in the past,” Munir said. “But now we feel this is the only way. We want to convey a sense of participation, a sense of ownership to the farmers. Once they invest in the reconstruction of the watercourses, they will maintain them better because they think they are the owners.”

There may not be a lot of time left. At partition in 1947, what is now Pakistan contained some 30 million people; 40 years later, the population had passed 100 million and was growing at an annual clip of three percent, one of the world’s fastest rates of population growth. It’s still a well-fed nation, thanks to the adoption of the higher-yielding wheat seeds of the Green Revolution, the development of new water supplies from the big new dams and the wells, and–most importantly–the forced jettisoning in 1972 of Bangladesh, a net importer of food.

The serendipitous streak may continue, or it may end. Either way, a Malthusian day of reckoning looms unless Pakistan can find a way to keep its 35 million acres of irrigated land producing 80 percent of its food for an indefinite future. Nature never intended for 100 million people to live in the arid Indus basin, and unless they learn to husband the land instead of just farming it, Nature may eventually drive them out again.

©1990 Russell Clemings

Russell Clemings, a science writer for The Fresno Bee, is writing about salinity, selenium and the future of irrigation.