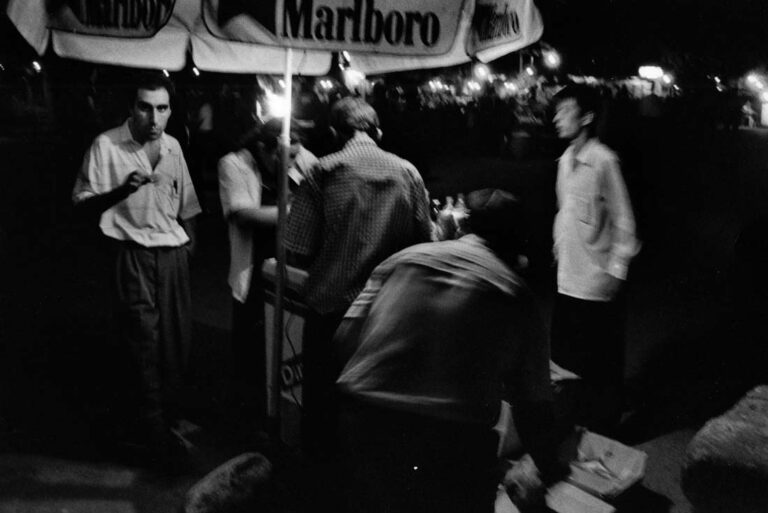

The first oil rush has attracted gangsters, spies and multinationals to frontier city Baku, Azerbaijan. At any hour in Baku you’re likely to run into Turkish “gangsters,” Chechen revolutionaries, Russian spies and oil men of every stripe, looking to make money any way they can.

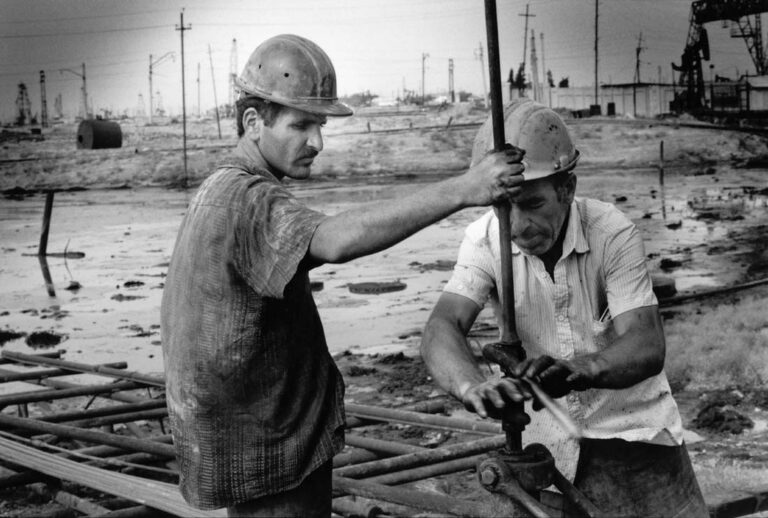

Azerbaijan is a former Soviet Republic located in a disagreeable spot just south of Russia and north of Iran. It is known for nothing except oil and the smell of it is everywhere.

I am spending time in Baku, not really focusing on the oil, but everything interconnected to it. The Hyatt Hotel is a central point for business in Baku, top business. I call it the great game 1998 style. Dick D’Amato, president of the Caspian Business Group USA, and Galib Mammad, executive director of the United States Azerbaijan Chamber of Commerce (“foreign agent for the Azeri Government in the USA?”) confer with Azeri deal makers. Americans lobby for oil and business concessions in Azerbaijan, and Azeries want money and better relations with the U.S. government, especially concerning the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

Azerbaijan is surrounded by enemies and the army is weak. The forces of Armenia and Azerbaijan, technically in the fifth year of a cease-fire, manage to shoot across the line virtually every day. They are building a pipeline a few kilometers from the border zone, but due to the tension in the region there is no ironclad guarantee that the oil beneath the Caspian will make it to the West.

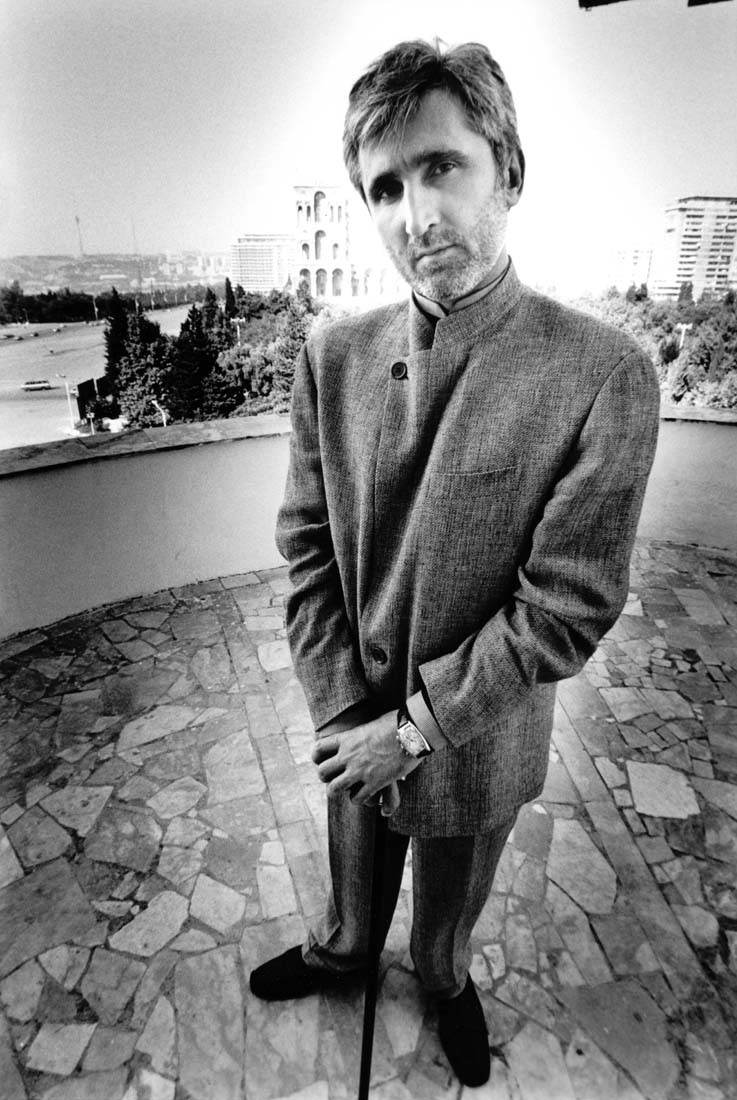

Players in the game are not only businessmen. I photographed the Minister of Defense, Safar Abiyev, in the secret Azeri war room in Baku: “Oil is our strategy. It is our defense. It is our independence.” And I photographed the minister of National Security, the former KGB. Also President Heydar Aliyev who protects the oil interests and the businessmen dealing with it. Through his presence at receptions in the Hyatt he shows the officials that they should leave the hotel alone. This way they keep hardcore gangster elements out, but a bribe here and there can open any door in Baku. You can’t directly bribe the president, but as someone said to me: “When you rule your country like a dictator you don’t need money in your pocket.”

Another player who may become important for the Caucasus is Khozh-Ahmed-Noukhaev, a former gangster and Chechen revolutionary and current head of the Caucasus Common Market. He wants to create a corridor from Chechnya to Azerbaijan, thus allowing business in these countries destroyed by various wars in the region.

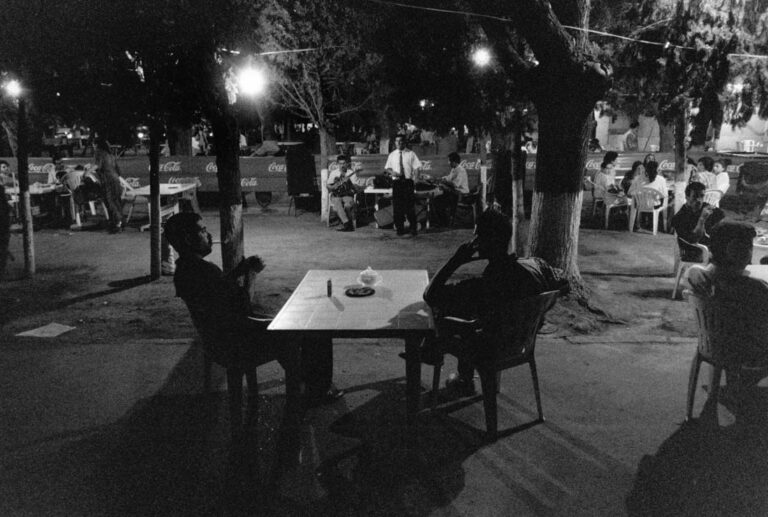

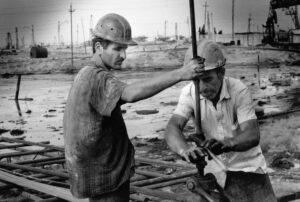

The streets of Baku show the thriving Turkish small businesses. Mercedes cars are everywhere for sale, even at night. This city is changing rapidly, but the oil workers are not getting anything from the cake. Their salaries didn’t rise with the prices of goods and food. At night you have two places to go, for those who have money and for those who don’t. The businessmen go to a disco. The real Azeri sit outside and drink tea and smoke a lot, participating or commenting on a game of Chess.

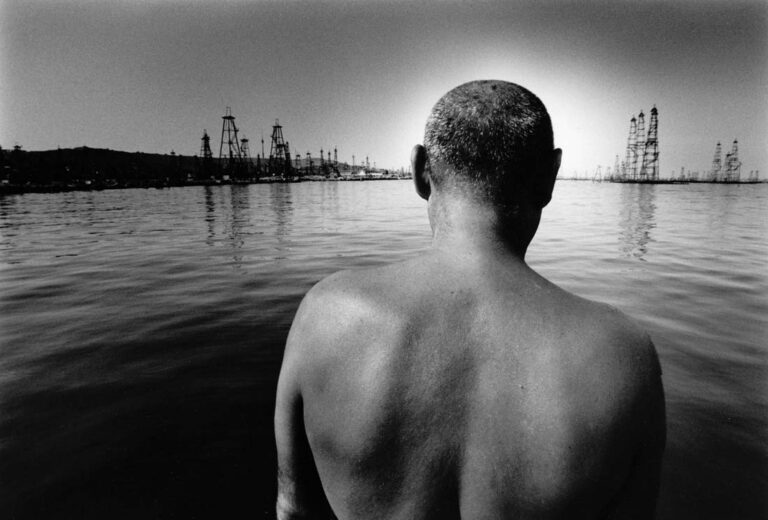

The people in Baku love fishing, even though they have the deserted old oil field behind them. They fish in the Caspian Sea. Children swim in oily sea water but have a lot of fun anyway. The ecological consequences are enormous and it is hard to believe that the health of these children and people who live with the oil day in and day out, will not be aggravated. On the other hand, outside Baku, you find health resorts where people apply oily mud all over their body and let it dry. They wash it off with salty water, coming from a natural spring. This oily mud is supposed to heal the sick body.

Meanwhile, a man overlooks his sea, the Caspian Sea, fishing for food, but knowing very well what the consequences can be.

©2002 Stanley Greene

Stanley Greene, who lives in Paris, is a photojournalism fellow.