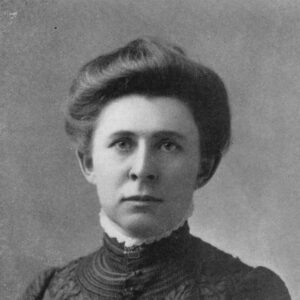

After rejecting an opportunity to expose the predations of the Standard Oil Company in the 1880s, Ida Tarbell decided to tackle a more limited, though still ambitious, topic. She simply did not feel prepared as a journalist to tackle the biggest trust on earth, the trust that twenty years later would make her famous when she eexposed its operations.

Many of her female friends had been pushing for universal suffrage. Tarbell, though a feminist in many ways—in deeds, if not words—doubted whether women could actually improve the world by winning the vote. She commented,

“There had been women in public life in the past. What had they done? I had to satisfy myself before I went further with my science of society or joined the suffragists. It was humiliating not to be able to make up my mind quickly about the matter, as most of the women I knew did. What was the matter with me, I asked myself, that I could not be quickly sure? Why must I persist in the slow, tiresome practice of knowing more about things before I had an opinion? Suppose everybody did that. What chance for intuition, vision, emotion, action?”

Tarbell lashed herself for her inability to make up her mind more quickly. Why were other women so much more decisive, she wondered. What if everybody deliberated as thoroughly as she did. But she found herself unable to change her ways—they were an integral part of her nature.

Tarbell was fascinated by Madame Marie-Jeanne Phlipon Roland (1754-1793, when she died on the guillotine), of French Revolution fame. Tarbell had published a brief profile of Roland in The Chautauquan [March 1891], but wanted to know far more. She understood that so long as she had regular duties at the magazine, she could never find enough time to research satisfactorily, just as she had never found enough time for her microscope while teaching in Ohio.

After an understandably indecisive stretch, in which she was both bolstered and hindered by the support and worry of her parents, Tarbell decided to leave for Paris, hoping she could support herself there through research and writing. Her friends and work colleagues tried to discourage her move. They told her she was too old for a career change, that she was acting superior. Tarbell determined, though, to expand her geographical horizons and her mind. Showing uncharacteristic aggressiveness, before departing she called on newspaper editors, some of whom agreed to consider her freelance articles at $6 each.

Freelancing did not go well at first. Just as she despaired, she started receiving more acceptances. Her most reliable newspaper outlets turned out to be the Chicago Tribune, Pittsburgh Dispatch and Cincinnati Times-Star. Tarbell tended to write about everyday life in Paris, which she was endlessly curious about. Why was the city so clean? How had the ruling classes decided to tolerate the beggar class? What did Parisians do for fun?

An unexpected sale of a short fiction story brought $100 from Scribner’s magazine. Tarbell based the story on her real-life French tutoring sessions with Claude, an elderly dyer in Titusville, and his mouselike wife. The story told about the couple’s desire to see France once again before dying. Tarbell handled her new-found cash horde conservatively.

Then she received an unannounced visit from a stranger, the American magazine editor Samuel Sidney McClure. At age 35, he was a novice at the magazine business, but had grand plans for a magazine named after himself. He certainly understood he needed as many outstanding reporter-writers as he could find.

Why Tarbell? While in his New York City office, sometime during 1892, he had by chance noticed and read her article from Paris, “The Paving of Paris by Monsieur Alphand.” When he had finished reading, he remarked to his partner, John S. Phillips, “This girl can write. I want to get her to do some work for the magazine.” McClure asked Phillips if he knew anything about the author. “No idea,” Phillips reportedly said, “but from her handwriting I should guess she’s a middle-aged New England schoolmarm.”

After becoming aware of Tarbell’s skills, McClure looked her up next time he traveled to Paris. As he recalled the visit,

I called upon her at her little apartment on the river, taking with me some newly discovered information about the Brontes upon which I wished to get her judgment. I went to see her, intending to stay 20 minutes, and I stayed three hours. The following year Miss Tarbell wrote several articles for McClure’s, one on Professor [Pierre-Jules-Cesar] Janssen and his observatory on the top of Mount Blanc, and one on the [Alphonse] Bertillon system for the identification of criminals.McClure liked how Tarbell had learned research techniques and theory from French historians, and also liked the soundness of her judgments. Tarbell was pleased that she had impressed McClure.

McClure later offered Tarbell a job in New York City on his fledgling magazine, its first issue appearing during the summer of 1893. She was interested. By then, though, she had begun researching a planned biography of Madame Roland. She had discussed the book publishing arm of Scribner’s contracting for the Roland manuscript.

Unfortunately for her, that decision made life harder. Freelancing from Paris continued to be marginal—McClure had little start-up money for his magazine, and a national economic depression in the United States did nothing to make fundraising easy. At one point, Tarbell pawned her sealskin coat to continue eating.

When she received a paying assignment, she undertook it with relish. The articles about science requested by McClure took Tarbell back to her high school and college enthusiasm for the microscope: “I found that, little as I knew of all these things, I still had something of a vocabulary and knew enough to find my way about by hard work.”

Her article about scientist Louis Pasteur filled 13 pages of McClure’s in September 1893. She showed Pasteur at home as well as working at his scientific institute in Paris. Tarbell found nothing about Pasteur to criticize; the article is entirely upbeat. She wrote some of it in the first person, letting her wonderment shine through. Though there is no sign of muckraking, there is evidence of relentless curiosity, a prerequisite for successful investigation. She felt she knew Pasteur well enough to render what he was thinking at certain moments in the present and the distant past, a psychobiographical approach that she would use when she wrote about Rockefeller, even though he never spoke with Tarbell.

Despite the interruptions that slowed her Roland book, Tarbell never lost interest. Tarbell’s research on the Roland biography certainly did not go as expected, although what happened moved her along the path to the muckraking that eventually made her famous.

When Tarbell first read others’ accounts, she idealized Roland as a heroine, a role model for women living a century later. That idealization led to Tarbell’s desire to research the life more thoroughly, on her own. But as Tarbell learned about Roland through original research, the luster dimmed.

Tarbell, who avoided romantic attachment and discussion of sex throughout her unmarried life, began to believe, to her distress, that Roland had become a French revolutionist as much because of the man she loved as from ideology. In addition, even when considered apart from her man, Roland seemed not so much wise as she did ambitious and vain. The biography, when published by Scribner’s in 1896, had a debunking tone—unusual for biographies of that era, but not unusual for the muckraking era less than a decade hence. Tarbell’s Roland biography turned out to be both a precursor and a bridge. The narrative approach employed by Tarbell to make the life of Roland as interesting as possible had been uncommon to that point, but would become the standard later in Tarbell’s career.

The themes of individual and collective responsibility run through the book, as they do through just about everything Tarbell wrote. The book is filled with interesting information to buttress the themes; Tarbell was already a first-rate researcher intent on evaluating a woman’s life rather than uncritically celebrating a martyred revolutionary. Tarbell was able to go beyond Madame Roland’s romanticized prison memoirs to learn about her through her less self-conscious, earlier personal papers, which had recently been made available by Roland’s descendants at the Bibliotheque Nationale. Madame Roland’s great-grandson helped Tarbell obtain and interpret the letters, as well as well-preserved notebooks from the revolutionist’s childhood.

When Tarbell had finished researching, analyzing and writing about Roland, it was time for a new project. Although the connection might seem remote at first, Tarbell’s work on Roland prepared her for exposés of more contemporary figures. Writing the Roland book helped Tarbell explain human nature to herself and others, how in most societies the few hold the power, abuse it, and sometimes spawn revolution by the many without power.

©1999 Steve Weinberg

Steve Weinberg, an investigative reporter in Columbia, Missouri, is examining the life of journalist Ida Tarbell.