It does not look like anything especially impressive today. It sits on an out-of-the-way shelf, one of millions of volumes in a cavernous university research library. Its green cover has faded after 93 years of heavy use, occasional abuse and, ultimately, lack of use. It is mentioned in Twentieth Century America history courses on college campuses. But hardly anybody alive has read it from beginning to end, all 815 pages of dense type.

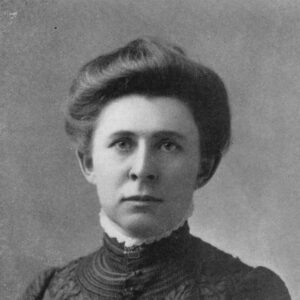

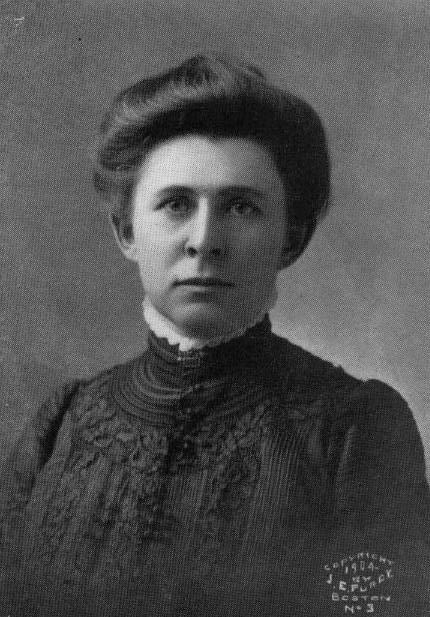

That is a shame, because the book is probably the greatest work of investigative journalism ever written. “The History of the Standard Oil Company” is the unprepossessing title. By Ida M. (for Minerva) Tarbell.

Born during 1857 in rural Pennsylvania, Tarbell was 43 when she started researching the world’s most powerful corporation and its chief executive, John D. Rockefeller.

By the time she started, Tarbell had won a measure of fame for her serialized biographies in McClure’s Magazine on Napoleon Bonaparte and Abraham Lincoln. Finding new material on those historical figures had been difficult. Rockefeller presented a different kind of challenge. He was alive, not dead, and at the zenith of his power. He had no intention of letting a mere journalist – and a woman, at that – assault his empire.

Tarbell’s biggest obstacle, however, was neither her gender nor Rockefeller’s opposition. Rather, her biggest obstacle was the craft of journalism. She proposed to investigate Standard Oil and Rockefeller by using documents – hundreds of thousands of pages scattered throughout the nation – then fleshing out her findings through well-informed interviews with the company’s executives, competitors, government regulators and academic experts.

In other words, Tarbell proposed to practice what today is considered investigative reporting. But in 1900, as she began her research, investigative reporting did not exist. Tarbell would have to invent a new form.

So who was this reporter willing to take on Standard Oil and Rockefeller? The biography of a woman born 140 years ago, who has been dead since 1944, might seem irrelevant today. But Tarbell’s childhood, adolescence and young adulthood actually yield timeless lessons about how to become a skilled truthteller.

Growing Up Curious

The development of a truthteller is a result of nature and nurture. Relentless curiosity is a primary requisite. The truthseeker is always wondering “why?” As will be seen, Tarbell possessed that relentless curiosity from a young age. The circumstances of her upbringing eventually focused that relentless curiosity on Standard Oil and Rockefeller.

That Tarbell grew up around the fledgling oil industry in northwestern Pennsylvania would influence her work, but she almost did not grow up there at all. After she had been conceived in Pennsylvania, her father Franklin Sumner Tarbell set out for Iowa to find land. He figured the income from land, combined with hoped-for earnings from his occupations as teacher and welder, would provide for the family. He expected to move his wife Esther Ann, a schoolteacher he had married after a six-year engagement, to Iowa before the birth of their first child.

Franklin Tarbell found his desired land in the southwest corner of Iowa, just north of the Missouri border. He arranged for the pregnant Esther to make the journey with their household goods in August 1857. If all had gone as planned, Ida almost certainly would not have become fascinated with the world of oil. Oil was not exactly abundant in Iowa. But an economic downturn during the summer of 1857 led to banks closing in Pennsylvania, Iowa and in between. Franklin and Esther could not retrieve their money; they were cut off from each other, about 1000 miles apart.

Amidst the confusion, Esther gave birth to Ida on Nov. 5, 1857, in Franklin’s absence. Penniless, Franklin began walking from Iowa to Pennsylvania. He stopped en route to teach in country schoolhouses so he could earn enough for food as well as replace tattered clothing and wornout shoes. It was the spring of 1859, when Ida was 18 months old, that Franklin finally reached Pennsylvania.

Franklin Tarbell planned to earn enough money to move the family to the Iowa homestead. He did so by returning to the flatboat piloting from his premarital days. The summer water route proved lucrative enough that the Tarbell family planned to set out on a return trip to Iowa. It was August 1859. Before the Tarbells actually set out, however, oil entered their lives. Franklin learned as he visited along the start of the route to Iowa that a prospector named Edwin L. Drake had drilled for oil near Titusville, Pa., previously a lumber town. If the Titusville well struck by Drake on Aug. 27, 1859 indicated how much oil was in the ground nearby, Pennsylvania might take the lead in lighting the world. Within six months, hundreds of wells lined the 16 miles between Titusville and Oil City along the Allegheny River.

Franklin decided to explore money-making possibilities in northwestern Pennsylvania before making the move to Iowa. When he saw the wells first-hand, he started thinking what the producers would need that they lacked. Storage tanks. A welder, Franklin believed he could construct tanks in quantity, each holding at least 500 barrels. He talked to a well owner, received an order, built a prototype, and received orders for more. There was money to be made; the Iowa homestead would have to wait.

Franklin opened a shop, then built a house nearby. In October 1860, the Tarbell family moved 40 miles from Erie County to their new home at the mouth of Cherry Run.

Young Ida disliked leaving the log house in Erie County, with its farm animals, household pets, fireplace, wooded area, and summer wildflowers. Just past her third birthday, Ida told her mother she was running away, returning to grandma’s in Erie County. Unsurprisingly, a three-year-old did not know her way, so soon returned to her mother. Ida said later she always remembered two lessons from the incident – first, that she would never again experience defeat if she could help it; second, that she could always return to her parents after a revolt without fear of rejection.

A relentlessly curious child, she undertook to learn the oil business that obsessed the region and her father. She found science, including earth science, fascinating. Ida noticed early that the oil business did no favors for the earth. She wrote in her autobiography: “No industry of man in its early days has ever been more destructive of beauty, order, decency, than the production of petroleum. All about us rose derricks, squatted enginehouses and tanks; the earth about them was streaked and damp with the dumpings of the pumps, which brought up regularly the sand and clay and rock through which the drill had made its way. If oil was found, if the well flowed, every tree, every shrub, every bit of grass in the vicinity was coated with black grease and left to die. Tar and oil stained everything. If the well was dry a rickety derrick, piles of debris, oily holes were left, for nobody ever cleaned up in those days.”

The Tarbells had no idea whether the boom would be long-lived enough to sustain the family. It turned out that the oil in the ground was plentiful. During 1861, well after well came in up and down Oil Creek. The oil discoveries carried dangers, especially around inexperienced men and women. On April 17, 1861, Franklin Tarbell and other townspeople were discussing the coming horror of a civil war when they heard an explosion. A light handled carelessly had ignited gas trapped in flowing oil. At least 19 bodies turned up quickly. Later that night, Franklin and Esther Tarbell heard mysterious sounds outside their door. A man burned beyond recognition croaked out his name. When the Tarbells realized it was a friend, they hastily turned their home into a hospital. Esther served as a nurse for the gruesome injured man. The nursing continued for weeks; Ida recalled the courage and stamina of her mother as she saved a life in a town without a hospital.

A Teenager Finding Herself

Ida’s parents tried to combat ignorance by spending hard-earned money for reading material. Ida read the incoming issues of Harper’s Weekly, Harper’s Monthly, the New York Tribune and books as they turned up in the house. On a lower intellectual plane, Ida snuck moments reading the forbidden Police Gazette, the property of men who worked for her parents in one capacity or another. Some of those workers slept in a bunkhouse built by Franklin on the hillside.

Ida commented in retrospect: “I looked unashamed and entirely unknowing on its rough and brutal pictures. If they were obscene we certainly never knew it. There was a wanton gaiety about the women, a violent rakishness about the men – wicked, we supposed, but not the less interesting for that. One reason the Police Gazette fascinated me was that it pictured a kind of life I knew to be flourishing in a neighboring settlement where my father had shops run by a boss who, as well as his sister, was a family friend and where I was often allowed to visit. This settlement, Petroleum Center, had by something like general consent become Oil Creek’s sink of iniquity. “

Recognizing the seamier side of humanity helped prepare Ida for the deceit investigative reporters unearth and try to fathom. After Ida had become accustomed to her surroundings, seamy and pure alike, the Tarbell family, during 1870, moved from Rouseville to Titusville. The family’s new house was striking in its architecture and is massiveness. Ironically, though, it was not a sign of increased fortune. As the oil industry suffered a downturn, Tarbell closed his Pithole shop. The owners of the Bonta House, a fine hotel, had to do the same. Franklin Tarbell paid about $600 for the building, which at one point had been valued at $60,000. He tore it down, then shipped the materials – woodwork, French windows, iron brackets – 10 miles to Titusville, where he had chosen a site for the new family residence.

Like the Tarbell family, the oil industry was undergoing a change; the potential for wealth attracted corporations that meant to push out independents such as Franklin Tarbell. Those corporations knew the independents lacked control of a crucial element – using railroads for transporting the oil products beyond the region. Franklin began to bring home tales of the railroads and large oil companies squeezing small firms like his.

The mention of John D. Rockefeller and the Standard Oil Company brought forth special enmity. The teenaged Ida listened carefully to the talk at the anti-monopoly gatherings. She knew about the pleas by her father and his colleagues to state and federal legislators. She watched her father turn from an easygoing companion into a somber and even depressed man. She would later say, “There was born in me a hatred of privilege – privilege of any sort. It was all pretty hazy, to be sure, but it still was well, at 15, to have one definite plan based on things seen and heard, ready for a future platform of social and economic justice if I should ever awake to my need of one.”

At age 15, Tarbell underwent a transforming experience that cemented her status as a studious knowledge seeker: “I had changed from a very serious and well-behaved little girl into a very naughty one. Somehow, I must have discovered what fun it was just to have a good time. Certainly I was pursuing a good time with a zest that absorbed me. I played truant whenever I felt like it. Even when I went to school I didn’t study. I almost never knew my lessons – and I didn’t care!

One day, when I failed, as usual, the teacher walked down from the platform and simply read the riot act to me. I shall never forget Mary French! A quite wonderful woman, whom I secretly and deeply admired. She told me the plain and ugly truth about myself that day; and I sat there, looking her straight in the face, too proud to show any feeling, but shamed as I never had been before and never have been since.

From that hour, I was completely changed. I never was late or absent, unless it was absolutely unavoidable. I studied my lessons – not because I had then any desire for knowledge but because I wanted Mary French’s good opinion. When I entered high school, at the end of that year, I kept up my good habits for the same reason; I did not want to feel again the shame that had cut so deep. Up to that time I had not had any real ambition – merely a desire for approval. I hadn’t thought of any goal for my effort. When, at the close of the year, I found that I stood at the head of my class it was a complete surprise to me.”

Tarbell found the sciences especially fascinating – zoology, geology, botany, chemistry. She could relate her days of exploring around her various northwestern Pennsylvania homes to what she was learning in school: “Now I could justify my tramps before breakfast on the hills, justify, my collections, and soon I knew what I was to be – a scientist.” As she read geology, it dawned on her that the Bible’s account of the world’s creation could not be squared with scientific fact. Even though the authors Ida was reading tried to explain geology in the context of Genesis, her previously unquestioning faith had been shaken – an experience shared by many other investigative reporters.

She did not jettison organized religion, however. Science, its potential replacement, lacked guidance for conducting human relations. The message of Christianity that Tarbell could not surrender was this: “Do as you would be done by.” In her family’s household, the Golden Rule was in evidence regularly. Family members worked hard to do or say nothing that would injure another; when they lapsed, apologies tended to come quickly.

Not everybody in Ida’s family harbored the same religious doubts. In Titusville, the Tarbell family switched from the Presbyterian to the Methodist faith, because Methodists had the numbers to build the first church. The family worshiped on Sundays, during the middle of the week, and every night during revival meetings. Tarbell pretended to hear the call and go forward one of those nights – not out of conviction but because she wanted to show off her dress. She realized her hypocrisy almost instantly. She turned the hypocrisy to good use by wondering how many other people acted one way while harboring secret thoughts. The distinction between appearance and reality became clear, a distinction a successful investigative reporter can never forget.

The explorations with her microscope had a practical edge to complement the quest for religious truth. Ida understood that skill in the sciences might help her gain college admission, something she desired fervently in an era when many young women would not have dared act on such thoughts.

As Tarbell advanced through her teenage years, she absorbed not only science but also her mother’s feminism. Esther Tarbell lacked an outlet for her feminism until the move to Titusville. Ida recalled at least two nationally known women’s rights movement crusaders, Mary Livermore and Frances Willard, who visited the Titusville home during her teen years. Ida never forgot how those women ignored her, while male visitors tended to show an interest in her. She noticed, too, that not all women agreed on which issues to push, which tactics to employ or whether suffrage was even desirable. Her complicated, later-to-be controversial views about feminism were beginning to form. Ida’s exposure to the debate contributed to her understanding that few issues are simple – another vital realization for an investigative reporter.

From her reading, listening and observing, Ida decided marriage was almost surely not for her, even though she admired women who reared children. In the household of her religious parents, Ida prayed that the God she was unsure about would nonetheless help her attend college and find a professional calling instead of a marriage.

Her first choice for college was Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y. It had just opened its curriculum to women. As Ida was preparing her application to Cornell, she met Lucius Bugbee at her home. He was president of Allegheny College, affiliated with the Methodist Church; it had become coeducational just before Cornell. Ida was impressed. In 1876, at age 19, she left for Allegheny College in Meadville, Pa., 30 miles from her parents.

At college, Ida Tarbell would continue to develop the traits that would, unexpectedly, make her a muckraker.

©1997 Steve Weinberg

Steve Weinberg, a freelance writer from Columbia, Missouri, is examining the life and influence of journalist Ida Tarbell.