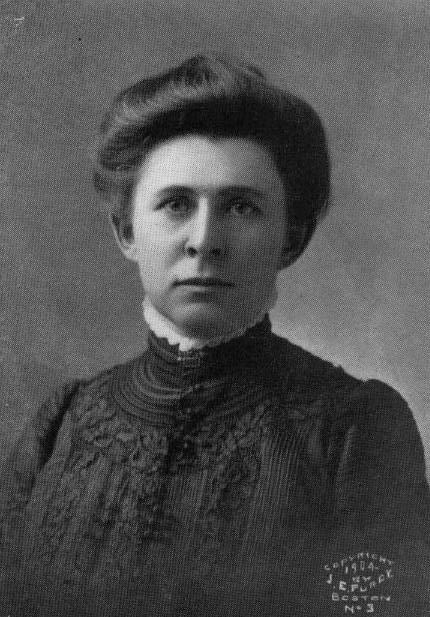

When Ida Tarbell left home in 1876 to attend Allegheny College in Meadville, Pa., she was doing more than advancing the independence of women during an era when most were denied higher education. Tarbell was also preparing herself, unwittingly, to produce the most significant work of investigative journalism in history — her exposé of the Standard Oil Company and its executive, John D. Rockefeller.

Tarbell’s relentless curiosity, the most significant trait of great investigative reporters, developed during her years at college and on her first job, as she built on the intellectual foundation of her youth and adolescence.

Allegheny College was not the ideal atmosphere for a female student, but Tarbell refused to be put down. She was the only female in her freshman class of 41. The sophomore class also was devoid of women. The junior class had two, as did the senior class. Ten women had graduated by the time Tarbell arrived, but they had failed to make much of a mark in the college’s atmosphere.

For example, every professor still was male. No boardinghouse had been readied for her arrival, and living in a male dormitory was out of the question. So Tarbell moved from faculty home to faculty home. Finally, a seven-room boardinghouse for the few female students, called the Snow Flake, opened behind an all-male dormitory.

Tarbell, with her positive outlook, decided to make the best of an awkward situation, finding knowledge and inspiration that would surface in her later career. Although sometimes chafing under the gender-based restrictions, Tarbell usually stayed away from the portions of campus designated as all male. In hindsight, she compared her experience on the college green with Virginia Woolf’s description in “A Room of One’s Own” of her own frustrating experience 50 years later. Tarbell read that book avidly in her old age. She found its theme in synch with her life — that women will reach equity with men in the intellectual realm when they have adequate independent incomes and rooms of their own for the solitude needed to create.

Tarbell suffered, as did many other students female and male, through long freezing winters in the campus’s unheated classrooms. The fires of learning kept her warmer than expected, though. What she learned in the science class of professor Jeremiah Tingley inspired her to label herself a Pantheist as she continued to wrestle with how to meld religion with the natural world. She reveled when invited to the apartment of Tingley and his wife, a childless couple who collected beautiful objects and loved new knowledge. Tarbell had never known anybody else who so openly gloried in the love of knowledge, who approached a vocation with such undisguised enthusiasm.

Other faculty members taught Tarbell other life lessons. Of her Latin professor George Haskins, Tarbell wrote that his “contempt for our lack of understanding, for our slack preparation, was something utterly new to me in human intercourse. The people I knew with rare exceptions spared one another’s feelings. I had come to consider that a superior grace; you must be kind if you lied for it. But here was a man who turned on indifference, neglect, carelessness with bitter and caustic contempt, left his victim seared…If it had not been for George Haskins I doubt if I…[would] ever have become the steady, rather dogged worker I am. The contempt for shiftlessness which he inspired in me aroused a determination to be a good worker. I began to train my mind to go at its task regularly, keep hours, study whether I liked a thing or not. I forced myself not to waste time, not to loaf, not to give up before I finished.”

She did well in her studies; upon graduation in 1880, she accepted a job as the lead teacher at a private, 32-year-old, Presbyterian-affiliated school in Poland, Ohio. Although she realized she might marry someday despite her independent cast of mind, she had nobody particular in mind. A salaried job would provide the independence she wanted, Tarbell hoped. But Poland Union Seminary turned out to be less than a liberating experience.

The founder, B.F. Lee, was still active enough to hire Tarbell. She had no hint at first she would be replacing the experienced and beloved Miss Blakeley. Her devotees found it difficult to welcome anybody trying to fill those shoes. Tarbell quickly determined that Miss Blakeley was worthy of the admiration. Within two weeks, Tarbell, not normally a quitter, wanted to leave. Quiet verbal support from Robert Walker, a local banker who served on the school board, kept her going as much as any other factor.

Poland Union Seminary was a combination high school/junior college by today’s standards, with continuing education for area teachers thrown in. Tarbell had to become knowledgeable about and teach geology, botany, arithmetic, geometry, trigonometry, English grammar, Greek, Latin, French and German. That variety built Tarbell’s confidence that she could learn about anything — an important mindset for a future journalist. As she began in August 1880 at a salary of $500 a year, she hoped the school would be a way station for a career as an eminent biologist, one who might solve the puzzle of life’s beginning, and thus of God. Journalism was not part of Tarbell’s plan at that point.

Living in rural Mahoning County, Ohio, taught Tarbell other lessons that would influence her later muckraking. Poland was only about four hours of non-motorized travel from where Tarbell had grown up, but in some particulars it was a world away. Poland itself was agricultural, almost barren of industry, but nearby cities were dependent on kinds of industry unlike the oil towns Tarbell had known.

She saw what happened to previously self-sufficient farmers when industry intruded. As Tarbell wrote in hindsight, industry brought “the destruction of beauty, the breaking down of standards of conduct, the growth of the love of money for money’s sake, the grist of social problems facing the countryside from the inflow of foreigners and the instability of work.” She visited sheep and horse farms and coal mines; she descended one mine shaft to see what it was like. Tarbell saw the beginning of slum housing areas in Poland and in the larger Youngstown, 10 miles away. Those areas surprised her: “Strange that [one such area] should be in a place such as Poland, but here it was — a disreputable fringe where a group of men and women had long been living together with or without marriage. You heard strange tales of incest and lust, of complete moral and social irresponsibility, and they were having a scandalously jolly time of it. Why I was not more shocked, I do not know; probably because incest and lust were almost unknown works to me in those days.”

She learned about unsafe factories — which would later become a major journalistic interest of hers — when a nearby iron furnace burst, spewing molten metal that burned workers to death. Tarbell did some of her exploring with Clara (Dot) Walker, the banker’s daughter, who was determined to see that Ida got away from the arduous teaching schedule as often as possible.

So the teaching job, including its geographic locale, had current and future benefits. But Tarbell realized most of them only later. In 1880, the drawbacks seemed to overshadow any benefits. After two years of relentless teaching at poor pay, she quit.

She still wanted to start a career as a biologist. She was rusty, though; her teaching schedule had left little time for microscope work. Returning to college to a graduate degree entered her mind as a path to a science career. She had almost no money, though, and her parents, hurt by an oil industry downturn, also had little money. In June 1882, at age 24, she returned to her parents — without a career, without any romantic attachments, without a plan. Tarbell found her home “open, wide open.” How easily her parents welcomed her influenced Tarbell for the remainder of her life to place family first.

Ida enjoyed many aspects of being in her parents’ home, but knew it could not and should not last. It was a meeting at the house with guest Theodore L. Flood that led to her departure for what she thought would be part-time, temporary employment on the magazine of the Chautauqua Assembly. Chautauqua was originally a summer camp stressing Bible instruction that had grown during the 1870s into a year-round hotbed of continuing education emphasizing science, history and literature. The group’s 10 times per year magazine had been expanding. Circulation grew to 15,000, then to about 50,000. Flood, the editor making the job offer to Tarbell, doubled as a temporary minister at the Methodist church attended by the Tarbell family; he had become a sometimes lodger at the Tarbell home.

Tarbell was not particularly excited about working at the magazine. But she had not held a paying job for about six months, believed she could handle the duties Flood outlined, and retained fond memories from participating in the Chautauqua movement growing up. “Indeed, it had been almost as much a part of my life as the oil business, and in its way was as typically American,” Tarbell wrote later. In other words, she had no compelling reason to reject the offer. The magazine, headquartered in Meadville, announced Tarbell’s hiring like this:

“This unique little paper will be enriched by the pen of Miss Ida M. Tarbell, a young lady of fine literary mind, endowed with the peculiar gift of a clear and forcible expression…Her wide ranging and versatile brain, together with her love for children and lively sympathies for Christianity, will make her services of rare value to young people as an editor of this paper.”

©1998 Steve Weinberg

Steve Weinberg, a freelance writer in Columbia, Missouri, is examining the life of muckracker Ida Tarbell.