Possibly “the most important revolution in human thought since the Renaissance.” William N. Ellis, who from his home in Rangeley, Maine, edits a “newsletter-directory” on appropriate technology groups and activities, made this immodest assessment of his subject in a recent issue of the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists. Ellis’ evaluation might be dismissed as a stab at self-fulfilling prophesy, but it is matched in kind — if by no means in kindness — by opponents of appropriate technology. A full issue of the bimonthly magazine of the Edison Electric Institute, an association of electric utility companies, was devoted last summer to challenging a main track of appropriate technology thinking, and this is a sample from that issue: “For the industrialized world to toy with such a set of ideas could be the beginning of an irreversible process leading downward, one from which recovery might be denied as problem piles upon problem and acrimony upon acrimony.”

What is this cause that seems to inspire the piling of hyperbole upon hyperbole? “Appropriate technology?” From an informal survey, nine out of ten people, far from thinking about appropriate technology as part of the beginning or end of a happy chapter in humankind’s history, have never even heard the term. Still, a quietly zealous band has gathered under the banner of appropriate technology, and their activities and thinking have been increasingly noted in the high councils of government and industry. “An idea whose time has come?” wondered Dun’s Review, a major business publication, a few months ago in headlines. And Congressman George E. Brown of California evidenced that the idea has at least come to Washington when he told a conference on energy the other day: “The emphasis on appropriate technology may well be one of the key cutting edges of beneficial change in our society today…” The possibility exists that, for good or bad, the appropriate technology movement and its philosophy have become a major social force in at least the last quarter of the Twentieth Century, a force, it would appear, of growing dimensions.

As Denton E. Morrison, a sociologist from Michigan State University who is currently on leave in Washington to explore the sociology of appropriate technology, observes, there has been a “mushrooming of centers, institutions, programs, personnel and publications aimed at implementing appropriate technology or its variants in developed as well as developing countries.” Mark Cherniack, co-editor of New Roots and an AT (as appropriate technology has become familiarized) activist working with the New England Appropriate Technology Network, says simply: “It’s everywhere, it’s all over the place, and it’s moving.”

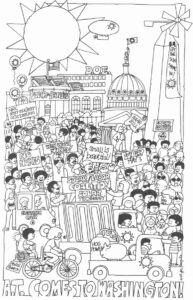

In the last two years, countless groups and government agencies, programs or projects have sprung up bearing the AT label or championing its gospel, including the National Center for Appropriate Technology, a federal agency under the government’s Community Services Administration; Appropriate Technology International, a non-profit organization set up and funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development; the Santa Clara (Calif.) Appropriate Technology Office, a country-level agency; California’s state-level Office of Appropriate Technology; the Long Island Appropriate Technology Group; the Paris-based International Network for Appropriate Technology; the Domestic Technology Institute, in Colorado; Intermediate Technology, Los Angeles; the Village Technology Center at the University of New Mexico; the Mid-Atlantic Appropriate Technology Network. The Department of Energy has been operating an appropriate technology grants program, the National Science Foundation has funded a survey of appropriate technology activities (one result, “Appropriate Technology — A Directory of Activities and Projects,” has some 200 domestic entries, 70 international), and, with Congressional urging, the NSF is considering formation of a full-fledged AT program.

Congress’s Office of Technology Assessment last year started a Task Force on Appropriate Technology. A group called Friends of Appropriate Technology, made up largely of government employees, now counts about 200 in its informal proselytizing network. Some of the stars of Washington have also declared themselves to be friends of appropriate technology, including Senators Kennedy and Percy. And some of the superstars of Hollywood, previously seen in anti-war roles, have recently appeared in pro-AT parts, including Jane Fonda, Robert Redford and Paul Newman.

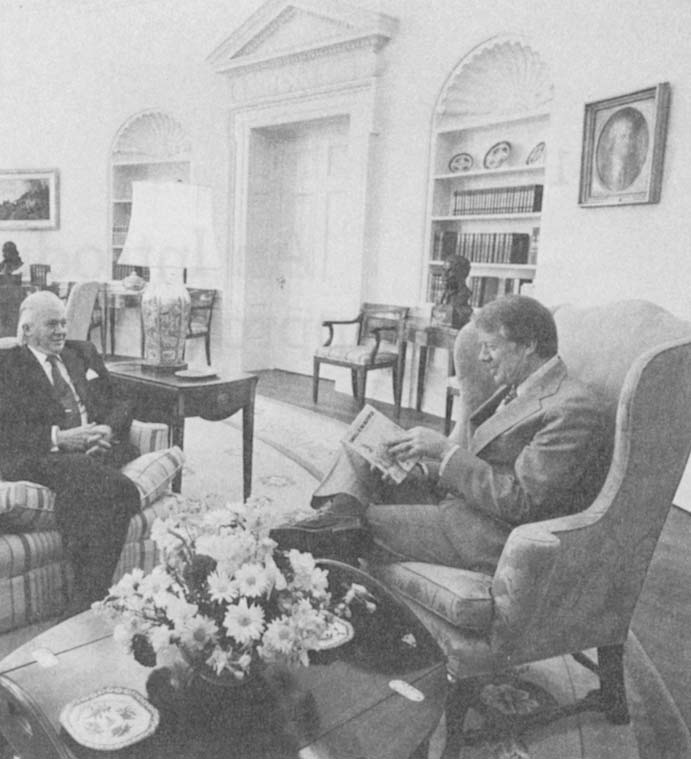

Perhaps the most dramatic signs of the growth of the AT movement were visible in the standing-room only audiences that greeted the late E.F. Schumacher, author of Small Is Beautiful and foremost philosopher of appropriate technology, during his six-week tour of the country last year. Governors and U.S. senators and other political leaders turned up to meet and introduce him as he crossed the country. And Schumacher capped his trip with an audience With President Carter, who echoed AT thinking a few weeks later in his energy message to Congress.

And perhaps the most visible current indication of the penetration of AT thinking is that the man who is generally regarded as a chief rival for Mr. Carter’s job, Governor Brown of California, is known as the foremost Schumacher fan in public office and is running for reelection to his own job largely on an AT — minded stand — against nuclear-energy.

On the surface, at least, it is highly unlikely and historically unprecedented, that anything like a mass popular movement should coalesce and advance in the cool name of technology. Nor can appropriateness itself be a very stirring rallying cry in a society that has so recently responded to invocations of freedom, equality, peace. Just what are the hopes and dangers, the causes and effects and implications of the appropriate technology movement and why does it seem to be sounding such a responsive chord at this moment in history? These are some of the broad questions I’ll be exploring in the course of this year, a year in which nearly everyone I’ve talked to who is familiar with appropriate technology feels a critical stage is at hand for the movement. III also be focusing on specific individuals, groups, activities and technologies themselves that are central to the movement and to an understanding of its appeals and significances.

But just what, to begin With, is “appropriate technology?” At the edges, the idea is vague and elusive, as vague and elusive as the terms “appropriate” and “technology” themselves. But there is an irreducible hard core to the phrase — the implication that much technology is inappropriate. That indeed is where the notion springs from and where much of its historical significance lies — in its challenging the desirability, even the long-range workability of much of conventional technology.

Not that technology and its predominant direction have not been challenged before. Social philosophers of one stripe or another have been worrying about aspects of modern technology and its social effects ever since the industrial revolution. Jean Jacques Rousseau and Adam Smith and Thomas Jefferson did so in the 18th century, Karl Marx in the 19th, and a host of culture heroes have so far in the 20th, including Henry Adams (who saw the cult of the Dynamo replacing the cult of the Virgin), Lewis Mumford, C. Wright Mills, Jacques Ellul, Paul Goodman, Herbert Marcuse, Eric Fromm, Ivan Illich. “A heavy and repetitious anthology could be composed of writings by all kinds of scholars lamenting the sacrifice of personality and freedom at the altar of technological regimentation,” writes Rene Dubos in joining the scholarly lamenters himself.

Still, modern industrial civilization as a whole has regarded technology as essentially benign and as virtually indispensable to humanity’s progress, the prospect of which was itself born with the surge of technological innovation in the 18th century. What’s more, the nature of technology, and its evolution in most realms toward larger scales and greater complexity, has generally been considered both desirable and inevitable, dictated by the laws of science and the marketplace.

It is the last supposition that is most profoundly challenged by the appropriate technology idea and movement. If some existing technologies are inappropriate and, as the movement asserts, alternatives are feasible, then technologies can come into use that are neither desirable nor inevitable; there may be other, better ways of doing things that for one reason or another have not been adopted. An AT premise is that societies have choices of technology to make and that such choices should be made consciously, democratically if possible, with society’s interest as a whole in mind, not accepted as givens or as being optimally guided by the interplay of private enterprise.

This idea began to take hold as a fully explicit, policy-guiding notion a decade ago, and it emerged in reaction to efforts to transplant “advanced” technologies from rich countries to poor ones. Appropriate technology thinking and activism was born in and has its deepest, firmest roots in developing countries where “technology transfer,” as the foreign aid people call it, has come in for increasing questioning, especially when the technologies being transferred are the massive industrial plants and complex processes of western technology.

Such technologies have been introduced with expectations of providing basic resources and impetuses for economic growth and betterment, but it is increasingly argued that many such introductions have served mainly to drain poorer countries of relatively rare resources, capital and energy, while ignoring or even contributing to an overabundant one, unemployed laborers. Some foreign aid examiners have also become concerned about such non-economic standards as “quality of life” and have started wondering aloud whether modern technologies did not in some cases do more to impair than to enhance life’s quality. Theodore Owens, who is deputy director of Appropriate Technology International, wrote a seminal book, Development Reconsidered, raising such questions.

But if “advanced” technologies are inappropriate and existing technologies in poorer countries are so crude as to offer little hope of improving their users’ lot, what technological course should be taken? Schumacher, after serving as an adviser to both Burmese and Indian governments, coined the term “intermediate technology.” (He may also have been the first to use “appropriate technology,” with roughly the same meaning, an etymological uncertainty I’m still trying to clarify.) In 1965, he also set up a private organization in London, Intermediate Technology Development Group, which designed and, in some cases, rediscovered intermediate technologies — “between the sickle and the combine harvester,” Schumacher used to say. A favorite example of his was an ITDG-developed machine that made egg cartons in relatively small numbers. Until then, the only existing egg carton machinery spewed forth many times more cartons than most rural areas could possibly use.

Designing and spreading intermediate technologies has been an increasing concern of many international aid organizations, both public and private, and AT-oriented organizations have blossomed in dozens of developing countries. Most notable among them is India, which in Ghandi’s exhortation to his countrymen to scorn foreign factories for cottage industries and spinning wheels has its own homemade philosophy of intermediate technology. The intermediate technology approach has not been universally accepted, to be sure. Some critics say that AT or IT is, above all, second-rate technology that developed nations are dispensing while keeping the best for themselves. A Soviet paper distributed at an international appropriate technology conference charged that AT was a western trick to keep poor countries from developing.

Still, appropriate or intermediate technology has taken a firm place in foreign aid circles, if it has by no means supplanted traditional large-scale “trickle-down” technology. And in the last few years, the idea that some forms of technology may be inappropriate began, in effect, to come home to developed countries themselves. The advance of AT in developed countries reflects, however, quite different currents of technological questioning. One stream was the broad challenging of institutions that erupted in the 60’s. Attacking the established institutional order as “the system” employed a peculiarly technological metaphor, in which there no doubt can be detected at least a subliminal antecedent to AT’s technological consciousness. Mario Savio, remember, carried the metaphor further when he urged Berkeley students to throw themselves on the machinery of the educational system. Indeed, some present day ATers define technology broadly enough to include social, political and educational as well as more purely technical systems, and it is clear that they are saying the same things as, but with only slightly different — and perhaps less inflammatory — terminology than the Savios, the Rudds. For that matter, there seems to be a fair number of 60’s radicals in AT ranks, including an oft-identified Schumacher fan, Jerry Rubin.

The mainstream of AT popularity in developed countries flows, however, not out of radical ranks so much as the environmental movement, Sociology professor Morrison, in fact, regards the AT thrust as basically a vigorous new direction in environmental thought and activity, “a revision of environmentalism,” he calls it. In the face of all the environmental ills that are attributed to the products and processes of a good deal of existing technology, appropriate technology seems to offer alternatives that amount to more than simply patching up the existing technology — attaching a scrubber to a polluting smokestack, for instance. Rather, as Morrison says, AT “attempts reform of the technological system as a whole.”

Most recently, technological questioning has been given a further substantial boost by prospects of increasingly scarce and costly supplies of petroleum, which fuels so much of our modern machinery. Whether we want to or not, it is evident that technologies designed to run on cheap fuel will have to give way to alternatives that are either considerably more efficient or, perhaps, profoundly different.

Put these impulses together with historic philosophic misgivings about the tide of industrial technology and you arrive at the definition of an alternative technological style that most ATers today subscribe to. There are distinct areas of emphasis among ATers which eventually may divide the movement, but for the moment this catalogue of characteristics is a generally accepted AT prescription for counter-technology: small scale, decentralized, subject to easier understanding and community control, environmentally innocuous, frugal in its use of resources, oriented toward renewable resources, involving creative work.

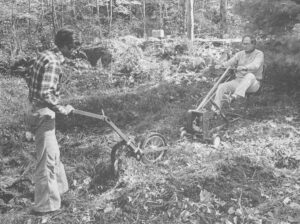

The actual technologies that appropriate technologists have been working to develop, have adopted or in some cases have revived to fit this bill range from elegant aquaculture and greenhouse techniques using minicomputers, to sail-powered freighters, to low pressure hydroelectric generators. At a far flank of the spectrum are even pedal-powered household and garden implements. The last are being developed on a commercial basis by what is probably the most successful of a growing number of AT-minded commercial operations, Rodale Press, publisher of Organic Gardening and Farming. Robert Rodale, the company’s president, isn’t sure that pedal power will catch on in the U.S. beyond, that is, the surge in bicycling in recent years, but he has a book out on the subject and the Rodale Resources Division has developed and is currently refining a multi-purpose power device called the Energy Cycle. ATers have also been tinkering for years with windmills and with devices to collect and store methane gas from manures and fermenting vegetation.

AT technologies tend to cluster around two areas — energy and agriculture — and two main examples of appropriate technology actually at work lie in “organic” growing, or “eco-agriculture,” and in solar energy, both of which I plan to examine closely later on. AT’s counter-technology in these areas comes in the face of their increasing centralization and mechanization of production and what is seen as a growing reliance on dangerous or potentially dangerous processes. In agriculture, ATers deplore technological “advances” characterized by ever larger scales of operation, more giant machinery and greater infusions of highly toxic pesticides and fertilizers. And in the energy field, most ATers see the epitome of what they are against in the nuclear power plant.

The attraction of appropriate technologists to agriculture and energy production also no doubt reflects the relative ease of understanding and working with some of the technologies involved in these areas compared to, say, producing steel billets or transistors. Another appeal lies in the prospect of self-sufficiency that comes, at least in theory, with being able to produce your own food and energy. For the same reason, homebuilding is another if not quite as dominant a focus of the AT movement and its movers.

The quest for self-sufficiency, in fact, is a primary one for many ATers who feel, in the words of Paul Devore, who runs the technology education program at the University of West Virginia, the need to “return to the individual and to the community control over their lives, their personal development and the ecosystem around them.” Because it pulls together many of the elements of such mastery in a model of self-sufficiency, the work of an AT group called the New Alchemy Institute, based on Cape Cod, perhaps comes closest to epitomizing the technologies of appropriate technology. At their Cape Cod site, and more fully in a government-funded structure they built on Canada’s Prince Edward Island, the New Alchemists have been trying to design and put together mutually supporting processes and equipment that would provide all the energy, food and shelter needs for a family under one roof for no more than it costs to build a new home today.

The New Alchemists call their structures “arks” — reflecting the cataclysmic ecological apprehensions that earlier were the main explicit motivations of the group. Now, like most ATers, they seem more positively oriented. Indeed, the general optimism and confident pragmatism of the movement is undoubtedly an ultimate, emotional basis for much of its appeal to a society that has heard recurrent, varying scenarios of doom or decay in recent years. In his energy-conference speech last month, Congressman Brown took note of this element in asserting that appropriate technology “has to be considered an encouraging, optimistic way to solve-problems of social development…” Bethe Hagens, an editor of a Chicago-based AT publication called Acorn, even confessed last month at a session on appropriate technology at the annual conference of the American Association for the Advancement of Science that a lot of ATers were in the movement because they found the work they were doing was actually fun, And in an issue of the Futurist magazine devoted to appropriate technology, Rowan A. Wakefield and Patricia Stafford speculate that “the most important contribution of appropriate technology may not be its technical innovations, but its creation of an optimistic social possibility…”

Friends of the Earth/Tom Turner

If so, it will not be because the technical innovations in themselves are insignificant. It has become somewhat fashionable for ATers as well as their critics to declaim an AT emphasis on “hardware” and a supposed inclination to “technological determinism.” As in every movement, a vocabulary of sins has begun to sprout involving such terms. “Tech fix” is another one, which carries some of the same sense as technological determinism — the idea that if only the right technology can be found, social ills based on the wrong technology will be cured. Amory Lovins, main advocate of “soft” energy technology and the closest perhaps to being the successor of Schumacher as chief AT philosopher, is seen by some as the prime offender as far as technological determinism goes. Schumacher was ultimately equivocal in whether altering technology, in itself, would cure the ills of industrial societies. His last book, “Guide for the Perplexed,” as well as some of his earlier writings seemed to consider spiritual, metaphysical change as a prerequisite to substantial social betterment. But Lovins poses the prospect that if solar energy were widely adopted as a decentralized power source, political and economic power would likewise disperse *in the face of the autonomy of communities and groups that could fuel themselves.

But, wonder some ATers and their growing band of counter-challengers, can appropriate technologies themselves be widely adopted unless the powerful political and economic institutions that support and thrive on large-scale centralized technologies first become or are rendered agreeable. It’s a chicken-or-egg, which-comes-first kind of argument, in part, but, as III be later examining, it underlies a hesitancy and soul-searching that appears to be afflicting at least a sector of the AT movement and may affect the movement’s direction at this critical stage.

In any case, it may be that some of the technologies of the appropriate technologists are going to prove highly significant on technological and economical grounds alone. While many of their designs are amateurish and unrefined, the work of hobbyist tinkerers, some highly sophisticated, elegant devices and techniques may be coming out of their ranks. At least some rigorous technologists and scientists think so. Among them is Theodore Taylor, a nuclear physicist who spent much of his career designing nuclear weapons and now teaches at Princeton and is a member of the Center of Environmental Studies there. He calls the AT movement, “a remarkable explosion of creativity” — in areas, it might be added, where alternatives to existing technology are clearly going to be needed, where ATers, often as individuals and in small groups, seem to be doing much of the pioneering, and where practical wide-scale application, once considered truly dreamy stuff, seems to come closer and closer, like a zoom-in camera image, with each new expert assessment.

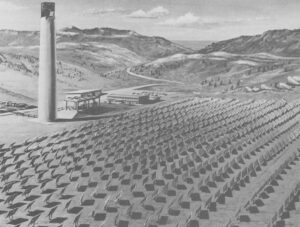

Solar energy, for instance. I plan to do a separate report on solar energy itself, because it is virtually the essence of technological appropriateness by AT standards. But, for now, it’s sufficient to note that the conventional wisdom has been and continues to be that the costs of collecting and storing solar energy are restrictively high and will be for a long time, too high to make solar energy more than a marginal element in U.S. or other industrial nations’ energy needs. A report prepared by a National Science Foundation — NASA group in 1972, for instance, saw solar energy as possibly providing in the neighborhood of 10 per cent of U.S. energy needs by the year 2020. A report on nuclear energy issues sponsored by the Ford Foundation last year speculated that solar energy “may provide a significant fraction of energy in the United States, but not until rather far into the twenty-first century, and with a price premium over nuclear or coal power.” But in mid-March Dr. Taylor, who is completing a study of solar energy for the Rockefeller Foundation, offered a radically optimistic new assessment to a review panel set up by the foundation. His finding, he explained to the panel, is that within the next half century, it is possible that “the whole world could come to depend entirely on solar energy” and that it would be available “at costs the same as or lower than [comparable energy sources] cost now.”

“That’s quite a mouthful,” said Taylor the other day. It certainly is. But evidence that he might be right can be found in the hardly ideological flocking of giant Corporations to solar energy, companies such as General Electric, Exxon, Alcoa, Grumman, and Dow Chemical. Some ATers are none too comfortable, to be sure, with such bedfellows, who they fear may co-opt and thereby undermine the social impact of their .technological pioneering. But that is another story, which I plan to get to next.

Received in New York March, 1978

Wade Greene, a freelance writer and author, is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner. His fellowship subject is “The Appropriate Technology Movement.” This article may be published with credit to Mr. Greene as a Fellow of the Alicia Patterson Foundation. The views expressed by the author in this newsletter are not necessarily the views of the Foundation.