“Jerry Brown vs. Jimmy Carter: Taking Different Paths to the Future.” That’s the headline in a recent issue of an anti-nuclear periodical called Critical Mass Journal. A lengthy sub-head reads in part: “California’s Gov. Jerry Brown is leading his state down the soft path. Carter continues to rely on nuclear power…both men are watching the political winds, as the 1980 presidential election looms.”

“Jerry Brown vs. Jimmy Carter: Taking Different Paths to the Future.” That’s the headline in a recent issue of an anti-nuclear periodical called Critical Mass Journal. A lengthy sub-head reads in part: “California’s Gov. Jerry Brown is leading his state down the soft path. Carter continues to rely on nuclear power…both men are watching the political winds, as the 1980 presidential election looms.”

The intriguing political scenario glimpsed herein is seen these days by a growing number of energy conscious analysts and advocates. Come 1980, the two main contenders for the Democratic nomination are President Carter and Governor Brown. Nothing very original about that lineup, but the issue that most clearly divides them in this projection is a novel one for the splanchnic grand prix of American politics, which usually revolves around charisma and direct pocketbook issues. Carter and Brown are seen as tilting over “hard” vs. “soft” energy paths, with the main confrontation centered on the increasingly disputed pros and cons of nuclear power.

In this scenario, Carter is seen as the defender of nuclear power, Brown the rejecter, the advocate of alternative, softer, lower, more “appropriate” sources of energy, such as sun power. The pairings of men and position are projected from a reading of recent stances by the two men and their administrations, including a growing tendency of anti-nuclear advocates to find a relentless priority for nuclear power in the policies and pronouncements of President Carter and his secretary of energy, James R. Schlesinger.

How real, in fact, is the divide between the two men as reflective, perhaps of increasingly politicized and polarized schools of thought about energy and technology? To explore at least one pole of the alleged polarization, I recently talked to Governor Brown and several of his aides who are involved in shaping his energy and “appropriate technology” policies.

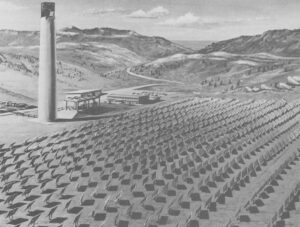

Signs of an anti-nuclear, pro-alternative-energy direction to Brown’s state energy program have been a main mark of the California governor’s administration in recent months. Brown proposed and, in late September 1977, signed a bill that gives that state the country’s largest tax incentive-a 55 per cent credit- for home solar installations. California now has a more ambitious solar goal, 1.6 million solar homes by 1985, than Carter has proposed for the whole country, 1.3 million. Brown has also pressed the cause of energy conservation, windmills (200-foot ones along the coast and in the mountains), use of biomass (including wood and woodchip burning), tapping the state’s geothermal resources.

Most significant perhaps was Brown’s threat to use a veto to prevent construction of a nuclear behemoth called Sundesert in the Mojave Desert. Legislation enacted last September decrees that no new nuclear power plant can be built until safe waste disposal means have been adequately demonstrated and approved by federal authorities. Because there are at least sizable questions about whether such means are at hand, the effect of the law, which was something of a sleeper, has been to bring a halt to nuclear power expansion in California. But the ink was hardly dry on the law when exemption was vigorously sought for the proposed 950 megawatt Sundesert plant.

“I blocked the Sundesert plant,” said Brown in one of the most assertive utterances during our talk in his office’s inaugustly homey visitor’s room. He spoke of “enforcing nuclear safeguard laws against the very strong opposition of business, labor and significant political forces.”

Brown also expressed uneasiness about nuclear power in general. “The question I think about and wonder about is what is the impact on the world progressively dependent on this radioactive material that lasts hundreds of thousands of years and can be converted into bombs.” Brown said his opposition to Sundesert “represents a recognition that the dangers of proliferation, sabotage, accident and waste management are serious problems that have not been adequately addressed in a public way by the governments of the world.”

Including the U.S. government? I asked, giving the governor an opportunity to cast a more singular aspersion toward Washington. But he pointedly ignored the question and at other points in the interview similarly avoided expressing criticism of or opposition to Carter on energy matters. He even suggested that interpretations of differences between the two men were media contrivances. “Well, people have to put a political handle on almost anything I do …You can’t talk a lot about California if you’re a journalist [for national or non-Californian publications] unless you link it to a national issue. There’s an institutional reason that whatever I do must be linked to Carter. Otherwise the expense accounts won’t be justified.”

Less combatively and more importantly, Brown seemed to be concerned above all with disassociating himself from zealous or ideological anti-nuclearism and with projecting an aura of reasoned pragmatism on the issue. “I like to take things case by case…I have devoted a sizable amount of time to carefully reading material on nuclear energy as well as other energy sources … There’s a lot of argument back and forth about what’s the risk, what’s the necessity. To the extent that the alternatives are attractive, to the extent that the risk is high, then the course is clear. To the extent that the risk is not all that clear and the alternatives are not all that clear, that leads you in the present direction of more and more nuclear power plants…In California, it seems to me that we have the space and the resources and the time to uphold our safeguards law and push alternatives…You want me to give a general view, but I’m learning as well as teaching…”

Brown suggested at one point that some of his aides may see the matter in less detached, more nationally contentious lights, and that was certainly so of most of the officials I talked to. Wilson Clark, Brown’s energy adviser since 1976-he worked for Carter’s campaign before coming to Sacramento- noted that Brown had recently met with Israeli officials about setting up a joint Israel-California solar research and development program. “You’d think the federal government would be interested, but the Department of Energy’s not interested in solar. They’re not interested in any of these [alternative] areas. It’s a crying shame. Their whole policy is designed to ignore lower technologies. Unless it’s a syn gas [producing synthetic gas from coal] plant or nuclear, they’re not paying attention to it.”

Why not? “The people that run it [the Department of Energy]. It starts at the top. Jim Schlesinger’s nuclear to the core…There’s no one in there that fundamentally has the philosophy that energy conservation makes any difference or that new consumer- oriented demand technologies are important.”

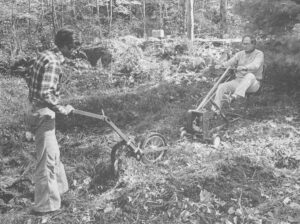

Sim Van der Ryn, California’s state architect feels much the same way and says so. Van der Ryn is currently planning three new solar-heated and -cooled state office buildings for Sacramento. He’s also chairman of the governor’s committee overseeing the state’s Office of Appropriate Technology. He and Clark are good friends and I talked to Clark at Van der Ryn’s own solar-heated house near the coast north of San Francisco. As it turned out, I talked to Van der Ryn himself in his Sacramento office whose clutter included a 10-speed bike and a stack of unassigned certificates saying: “In recognition for showing a way to live lightly on the earth, the Office of Appropriate Technology confers this award of merit.” Van der Ryn made it clear that he wasn’t planning to send any of the certificates to Washington. “At the federal level,” he said, “there’s no real commitment to conservation. What the hell are they doing? Nothing’s going on.”

Clark blamed Schlesinger for what he saw as shortcomings in national energy policy, rather than Carter himself. But Van der Ryn didn’t make intramural distinctions. When I suggested that the view of Carter as pro-nuclear and Brown as pro-alternative might be overly simplified, he said, “No, I don’t think it’s too simplified.” Then, echoing some of our earlier discussion about appropriate technology, he went on: “I think the reason the whole nuclear issue is so charged and so loaded is that pro-nuclear views [reflect] how people view the role of technology in society and where it’s going to take us . . . In the whole assumption that you have to have nuclear energy is the assumption that we are still on this upward curve, that there’s a direct correlation between income, productivity, capitalization per job, energy usage. And the reality is that that discontinued in 1973. The curve leveled off and went downward. To me, the writing is there on the wall. The society is falling apart and choking on too much energy use.

“If all [nuclear safety issues) were solved, I would still be opposed to nuclear power because I think our society is falling apart because of energy addiction per se. That’s my basic ideological position.”

But is it Brown’s? Though he once did, Brown hasn’t had much to say of late about small being beautiful or about the “era of limits.” Has he in fact moved away from such thinking? I asked him. “I believe that change occurs over time,” he said. “It’s evolutionary and so it’s not an abrupt jump from one style to another. Society is organized around some very large technologies-automobile manufacturing or power generation or telephone communications. These are the realities that impact people. So that is, so that has to be faced. The important thing is to create space, to carry themes on different paths.”

I observed that Republican aspirants to his job-some of whom polls showed to be narrowing the wide gap Brown once commanded over any projected opponent-were chiding him for his small-is-beautiful thinking. They had also been trying to make a major issue out of Brown’s opposition to Sundesert, linking nuclear power to jobs and economic vitality.

“Well, the paradox is that California is growing, including jobs,” said Brown. “In ’77, job creation was 70 per cent greater than the national average excluding California. Corporate profits were twice as high in California. Our net population growth is almost twice the national average. And that’s the paradox. I think there’s more understanding of the small-is-beautiful approach and that we’re still a land that’s experiencing expansion.”

If that sounded a lot like large-is beautiful, Brown turned reflective and ambivalent again. “We haven’t learned to manage growth yet. We haven’t really learned. The pressure from minorities, poor people, labor unions, is to just push the growth machine faster, because they don’t see a viable alternative, and it’s very hard for some well-supported middle-class person to say, ‘Well, don’t worry, we’re just going to have a little cottage industry here.’ That’s really not a politically or even humanly tenable approach.”

Is there a limit then to how much alternative energy sources can be pushed? “The limit is that people have the right to have a job, and it’s untenable to say, ‘We will experiment while hundreds of thousands of poor people are out of work or uncared for in mental hospitals.'”

Significantly, Brown pointed out several times that in place of Sundesert he was proposing a large coal burning power plant. It’s not nuclear, but to many environmentalists and appropriate technologists coal generation’s air pollutions and economies of scale make it almost as bad. Brown is also, I learned moving to assure petroleum supplies for California as ardently as he is toward windmills and toward converting the state capital’s furnace to burning woodchips. “I have come to see, Brown has convinced me,” Van der Ryn said, a little plaintively I thought, “that if we’re going to make a transition we’ve got to have these back-up sources.”

The last Brown aide I talked to, at his magazine office in Sausalito, was Stewart Brand, editor of Co Evolution Quarterly, which is one of the foremost appropriate technology journals. Brand serves one day a week as special consultant to the governor. While a mouse scurried in and out from under bookshelves in the waterfront quarters, we talked about the appropriate technology movement in general (Brand felt it appealed to basically religious yearnings) and about Brown’s energy directions in particular. I said that while it seemed clear enough, after all, that Brown was emphasizing certain areas more than the Carter administration, I got the feeling that when it came right down to it he hadn’t totally closed the door on nuclear.

Brand said, “This is not a door-closing politician. I don’t know anything he’s closed the door on. He does not close his mind on anything.” Then he explained that Brown had privately ruminated on “how out of it the solar backyard goofs might be, and what are you going to do if all these little trinkets, that’s all they are, and meantime we’ve got an industrial society to keep going through the rest of the century and you’re out there not even able to make a stove work. He’s constantly questioning himself, particularly on things that he thinks are probably the case or that he’s got going as a policy.”

All of which suggests that if you apply pathway analogies, which a good many energy- conscious people are inclined to do ever since Amory Lovins’ anti-nuclear essay, “The Path Not Taken” appeared, Brown may be bending in one direction, but he seems determined as yet to avoid going down any roads that don’t allow for a U-turn. This determination no doubt reflects Brown’s education in the complexities and uncertainties of energy supply and demand since he has been governor. At election time, it also no doubt reflects a concern not to scare the voters or arm the opposition with specters of novel excursions along paths not previously taken or yet fully scouted.

©1978 Wade Greene

Wade Greene’s Fellowship study is on the “Appropriate Technology Movement.”