Florida Congressman Claude Pepper huddled quickly with other colleagues after the U.S. House voted to exclude Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. on March 1, 1967. Powell was the first House member to suffer such a fate since 1919, when the House excluded Victor Berger, charged with violation of the Espionage Act. Powell immediately threatened to fight his ouster in federal court. Pepper suggested to House Speaker John McCormack that they go to New York City and talk with Bruce Bromley about handling the Powell legal challenge.

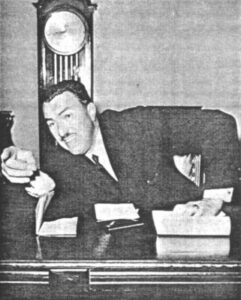

Bruce Bromley had credentials. He was one of the most prominent trial lawyers in America at the time. Bruce Bromley was Harvard Law. He was Cravath, Swaine & Moore, a silkened law firm, perhaps New York City’s most admired. Bruce Bromley had achieved prominence in American legal circles by simply working hard, much harder than the other lawyers around him. He found something almost soulful in drudge work. A colleague would say of Bromley that he “read documents and painstakingly studied and edited drafts of briefs, leaving the rest of us gasping at his continuing practice of phoning post-midnight changes to the printer.” The Bruce Bromleys of the world clawed their way to recognition. Ticking of clocks did not bother them; time was on their side. The law and legal work had a permanence all its own, and time would circle back, to them, for them, giving them youthful energy for a long time. The sophisticated cases at Cravath. Swaine & Moore would come across his desk soon enough: Westinghouse Electric, Bethlehem Steel, General Motors. He won the big cases for the big corporate giants. In 1949, Gov. Thomas Dewey appointed Bromley an associate judge of the Court of Appeals.

Bruce Bromley had a legend, but it was low-key, it was almost anti-legendary. He was fond of telling colleagues, in the heat of battle, when backs were against the wall, “No way we’ll win this case. It will take a miracle.” Then he would deliver the miracle, and wouldn’t fuss about it, because there was another case on the docket, another miracle to be offered.

Emmanuel Cellar, the brainy and streetwise chairman of the Judiciary Committee, sensed trouble early in the Powell legal battle, not for Powell, but for his House colleagues. Cellar felt Powell had a good case for taking his exclusion to court.

Powell would go to federal court first, then vowed, if that didn’t work, to go all the way to the Supreme Court.

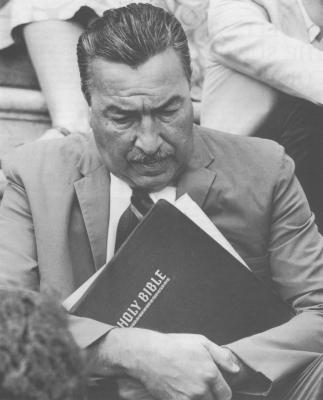

On the day Powell was excluded, Herbert Reid, a Howard University law professor, rushed to Powell’s office. Reid had first met Powell at Harvard Law School in the 1940’s, when he was a student. Powell was a young New York City Congressman at the time, everywhere in the news, always in the headlines. Now Herbert Reid was on the faculty of Howard Law School, teaching young minds, but never refusing to find the time to fight a civil rights case when he could. Howard Law School had a tradition to uphold. Howard had produced some great black legal minds, Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall among them. Powell asked Reid to take on his case.

The case suddenly had turned into a cause. Reid telephoned Arthur Kinoy, teaching at Rutgers Law School in New Jersey. Arthur Kinoy had a reputation as one of the most astute lawyers in the field of constitutional law. He was a short, rumpled man who wore thick glasses. He had seemed to love taking on the establishment, not to gloat after a victory, but to spread the boundlessness of constitutional law around. Arthur Kinoy had been involved in cases from the Rosenberg trial to the Montgomery bus boycotts, from the McCarthy hearings to Massachusetts labor disputes.

Kinoy recruited William Kunstler. Kunstler was a huge man. He read poetry. He settled his glasses atop his head. He let his hair grow long. He was old and he was young. This kind of case was his perfect cup of tea.

“The legal bidding was that we didn’t have a chance,” recalls Reid. The Powell legal team logic turned on one simple question: After a congressman had been duly elected, meeting the election requirements, could Congress determine him or her fit to be seated? The legal team thought not. “There was no way they could determine who could sit,” Reid said of the members of Congress.

Kinoy, Kunstler and Reid recruited Jean Camper Kahn, who at the time was on the staff of the Antioch Law School. Robert Carter and Frank Reeves, two other lawyers, came aboard. Many of them had recently been involved with the case of Julian Bond, in the lawsuit Bond v. Floyd, argued in 1966. Bond was a Georgia State Representative denied his seat by the Georgia House for his outspoken views against the Vietnam War. His case went to the U.S. Supreme Court, where it was won.

“We saw the case as part of the movement,” Kinoy says of the Powell challenge. “It was a fight that had to be made.”

So they gathered, to begin the drudge work of finding precedent after precedent. Their law school students gathered to help with the work. The students would be lucky in the future to come across a case of such complexities. They found case after case, showing the House of Representatives had no legal authority to refuse to seat a duly elected member. It was bigger than Powell, Kinoy kept telling everyone. The Constitution itself was at stake, he’d say.

Both sides were aware of the dimensions. “We were aware,” said Thomas Barr, who worked on the case with Bruce Bromley, defending the House’s actions, “that this was an historic case. One of the very few cases where two co-equal branches of government collided.” Another lawyer at Cravath would recall that the case was hugely popular. “All the young lawyers wanted to work on it,” recalls Jack Hupper.

On February 28, 1968, the U.S. Court of Appeals in Washington, D.C. ruled against Powell. The Powell attorneys positioned themselves to carry their case to the Supreme Court. On November 18th of that year, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear arguments in Powell v. McCormack.

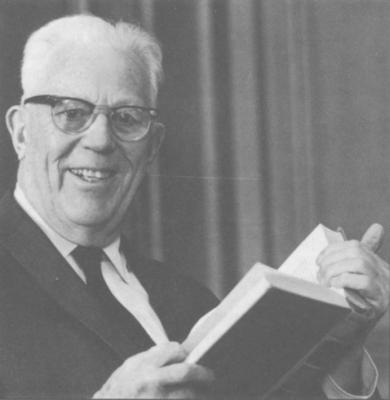

On April 21, 1969, the case began before a packed Supreme Court. Chief Justice Earl Warren presided over the court. Also on the bench were Hugo Black, William Douglas, John M. Harlan, William Brennan, Potter Stewart, Byron White, Abe Fortas, and Thurgood Marshall. The Warren Court had been one of the most activist courts in history. It delved into social issues with an alarming degree of regularity. It was the court that outlawed school desegregation in the Brown vs. Board of Education case; it expanded the rights of criminals in the Miranda ruling. It also was a much-maligned court. There were, in many pockets of America in 1969, huge billboards that said, “Impeach Earl Warren.”

“We rise this morning,” Kinoy said to the court in his opening statement, “to argue this case with a sense of grave responsibility. This is, as Chief Justice Marshall said of Marbury against Madison, a case of peculiar delicacy.” Kinoy went on to tell the court that the issues raised in the Powell case, of how much power Congress has to discipline one of its own, “strike at the very heart of representative government.”

Few were better than Arthur Kinoy in the courtroom, turning on his heels, reciting from memory facets of constitutional law. Kinoy placed Powell and the Congress not in terms of personality clashes, but in terms of the Constitution, its stated goals and protections. Facing the justices, Kinoy said, “This question was first answered in 1787 at the Philadelphia Convention. The power was grounded on no technical word interpretation, but upon a profound conception of fundamentals of representative government, for the founders determined that the legislature was to have no power to ignore, to alter, to add to, to change in any way the fixed qualifications in the written Constitution, for to give such a power to the Legislature was, in Madison’s words, ‘improper and dangerous.’” To ignore the precedent, Kinoy argued, would “turn history on its head.”

Herbert Reid went on to point out another step made by Congress, that there were differences, tiny as they might sound, between the words exclusion and expulsion. Expulsion might have been a legal remedy, Reid told the court; exclusion, he said, clearly was illegal.

Bruce Bromley was the oldest lawyer in the courtroom. He was savvy enough to have tricks up his sleeve. Bromley’s argument was that the judiciary had no business in the affairs of the United States Congress, that “each house shall be the judge of the elections, returns and qualifications of its own members,” and furthermore, that “each house may determine the rules of its proceedings, punish its members for disorderly behavior, and, with the concurrence of two-thirds, expel a member.”

Then Bruce Bromley told the court a telling admission: “I recognize that it has a strange sound coming from any lawyer to tell this Court that something unconstitutional may have occurred, and yet you have no power to intervene, but I make that contention in this posture and I rest it squarely on the speech or debate clause as interpreted by at least three cases decided here under that clause.”

Bromley aide Jack Hupper detected a shift in the case almost from the beginning. The justices’ questioning of Bromley seemed particularly harsh to Hupper. Justice Hugo Black asked Bromley, point blank, if he thought Powell was excluded because of race.

On Monday, June 16, 1969, the Supreme Court issued its landmark Powell v. McCormack decision in favor of Powell.

For those who had argued the Supreme Court had no business involving itself in the affairs of Congress, Chief Justice Earl Warren said, “It is the responsibility of this court to act as the ultimate interpreter of the Constitution.” The Warren opinion went on to say that to allow “power to be exercised under the guise of judging qualifications, would be to ignore Madison’s warning, borne out in the Wilkes case and some of Congress’ own post Civil-War exclusion cases, against ‘vesting an improper & dangerous power in the legislature.’”

In perhaps his most revealing passage, Warren said, “Our system of government requires that Federal courts on occasion interpret the Constitution in a manner at variance with the construction given the document by another branch.”

Powell’s legal team flew to Bimini. There was champagne and corks popped.

Bruce Bromley did not accept the defeat with any particular pain. He had been around long enough not to let defeats sink into his chest. The losses had to draft away like sawdust.

“The Supreme Court in this recent action has created a very dangerous confrontation between the two branches of Government,” Florida Congressman Samuel Gibbons said. “And I would hardly think that the House will bow to the wishes of the Court on this most important question.”

Republican Gerald Ford, of Michigan, was appalled at the decision. “This is an unfortunate transgression of the court on another branch of the Federal government.”

“It is not important that I won,” Powell said from the island of Bimini. “It is the American people who have a stake in this.”

Powell v. McCormack would be Chief Justice Earl Warren’s valedictory ruling on the Supreme Court. He would spend the rest of his life traveling and lecturing about the judiciary and the federal government, about ethics and responsibilities. President Dwight Eisenhower had elevated Warren to the high court, believing he would practice judicial restraint. Of all his high court appointments, Eisenhower often would mention that he regretted Warren’s the most.

©1989 Wil Haygood

Wil Haygood, a writer for the Boston Globe, is examining the life and times of Adam Clayton Powell, Jr.