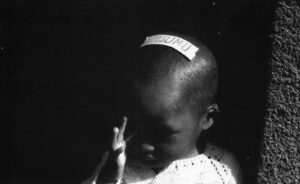

On a Sunday morning in June in the ravaged Rwandan town of Kabuga, on the outskirts of Kigali, the capital, tens of thousands of hungry and bewildered men, women and children wandered aimlessly amid the wreckage of their lives.

In the previous two months as many as half a million Rwandans, mostly minority Tutsis, had been systematically slaughtered after Rwanda’s president, Juvenal Habyarimana, was killed in a suspicious plane crash. Both the United Nations and the U.S. State Department have used the word “genocide” to describe the carnage.

(Photo by Mary Jane Camejo)

Among the survivors now living amid the looted ruins of Kabuga was Bonaventure Niyibizi, a Tutsi economist who lost his mother, sister, five nieces and nephews, four uncles and their families –more than 50 relatives in all. I asked him how Rwanda might overcome this tragedy. “There is only one way,” he replied. “That is to find the people who are responsible for this and to bring them to trial according to the law. People who have murdered have to be punished.”

Rwandans are still a long way from holding anyone accountable for the horrors that seized their mountainous central African nation last spring. But if they hope to do so they might look across their northern border at Uganda, which endured a comparable conflagration in an earlier era. In the 1970’s and early 1980’s, Idi Amin, and the less notorious but no less wanton Milton Obote, plunged the country into a nightmare every bit as dark and sinister as the one last spring in Rwanda. Perhaps a million Ugandans were killed in two decades of sheer terror.

Today Uganda is largely at peace. It is an extraordinary achievement, all the more so because of the murderous divisions now consuming nearly all of its surrounding neighbors. Yet there are doubts about whether the peace will last, in part because Ugandans have shied away from holding individuals accountable for the crimes of the past; a great many Ugandans who murdered have not been punished. Uganda’s experience, for better or worse, is a cautionary tale that Rwandans would do well to learn from.

The VIP lounge at The Nile Hotel in downtown Kampala, Uganda, is directly below room 311. In the 1970’s and early 1980’s Room 311 was a torture chamber. Beatings, whipping, electric shocks, burns on the chest and testicles — the cries emanating from room 311 may or may not have been audible down on the second floor, where Presidents Idi Amin and Milton Obote occupied rooms during some of their years in power. Today the Nile Hotel is metaphor for Uganda, a flourishing enterprise with a fresh coat of paint. Room 311 is a plush suite with crimson carpet, glass table tops and a super-chic bathroom, and Gideon’s Bible on the bedside table. “It’s a different story altogether,” the receptionist who showed me the room told me. “It has shed a bad name.”

Sitting on a sofa in the VIP lounge, sipping from a glass of passion fruit juice, was the man who ousted Milton Obote in a coup in July 1985, Major General Tito Okello Lutwa. Tito Okello commanded the force of Ugandan exiles who, along with the Tanzanian army, invaded Uganda in 1979 and drove Idi Amin from power. The forces under Okello’s command then helped Obote steal the 1980 general election. From 1980 to 1985 Okello was Commander of Obote’s army, the Uganda National Liberation Army (UNLA).

Under Okello’s command UNLA soldiers slaughtered thousands of civilians in Amin’s old stronghold known as West Nile. They killed tens of thousands more, possibly hundreds of thousands, in the region north of Kampala known as Luwero Triangle, where Yoweri Museveni’s guerrilla insurgency was based.

During Okello’s six-month tenure as head of state, Kampala disintegrated into Beirut-like fiefs controlled by warlords and murderous gangs. Museveni’s guerrilla forces seized the capital in January 1986 and Okello fled into eight years of exile. He was invited back in November 1993 with the promise of an amnesty — and armed protection.

Tito Okello would appear to be a war criminal. That he is back in Uganda now is a testament to President Museveni’s strategy to bring lasting peace to Uganda through co-optation rather than confrontation. Hundreds of soldiers and their leaders from the myriad erstwhile fighting forces, police and intelligence units, private militias, and bandit gangs, as well as numerous civilian officials from previous regimes, have been lured out of the bush or exile, and integrated into Museveni’s umbrella-like National Resistance Movement (NRM), and its army, the National Resistance Army (NRA).

Museveni’s goal is reconciliation. The success he has achieved thus far has been widely hailed as a beacon of hope for a turbulent region that includes such devastated neighbors as Sudan, Somalia and now Rwanda. But co-optation rather than confrontation has had a price: a great many Ugandans have quite literally gotten away with murder.

Tito Okello is now 80-years-old. Carrying a carved gold and ebony cane, dressed in a dark brown suit and a blue necktie with a pattern of crossed Winchester rifles, Okello seemed fit, good natured, wily. It was “love of my country” that brought him back, and the lure of “15 to 20 grandchildren,” Okello told me. I asked Okello if he has any crimes to answer for. “Even up until now, people still like me,” he replied. “I am a man of peace.”

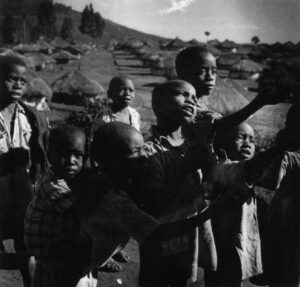

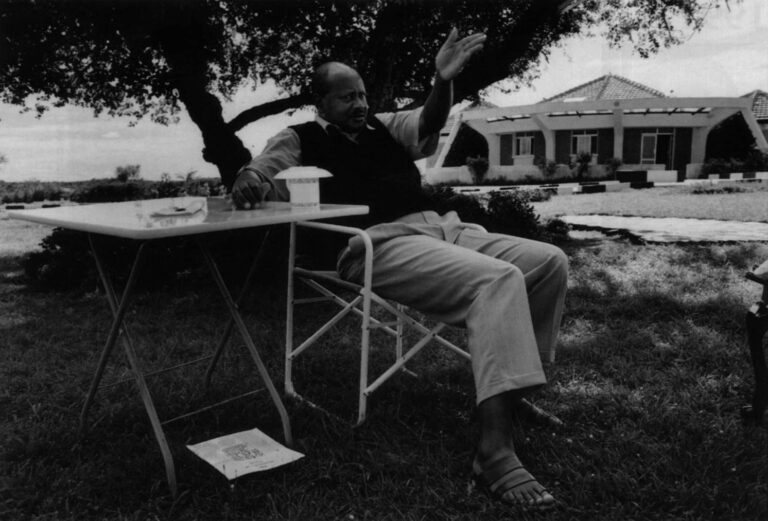

(Photo by Mary Jane Camejo)

At the time of my visit earlier this year, all of Uganda’s neighbors were in turmoil. To the south, both Rwanda and Burundi were convulsed by ethnic slaughter in which hundreds of thousands are believed to have been killed. Zaire, on Uganda’s western border, was in the throes of “ethnic cleansing” as Mobutu Sese Seko maneuvered to survive in power. To the north, thousands of Sudanese were in flight from the Sudanese army’s latest offensive against southern rebels as Sudan’s civil war entered its second decade. Even Kenyans, on Uganda’s eastern border, who for years had viewed Uganda’s agony with a mixture of horror and disdain, were beset by yet another round of state-inspired ethnic clashes that have shaken Kenya’s reputation for stability.

Uganda, of all places, seemed like a model of tranquility. A decade earlier I had felt a rush of relief as I exited Uganda across its southern border and entered what was then pacific Rwanda; this year I experienced precisely the opposite sensation.

(Photo by Mary Jane Camejo)

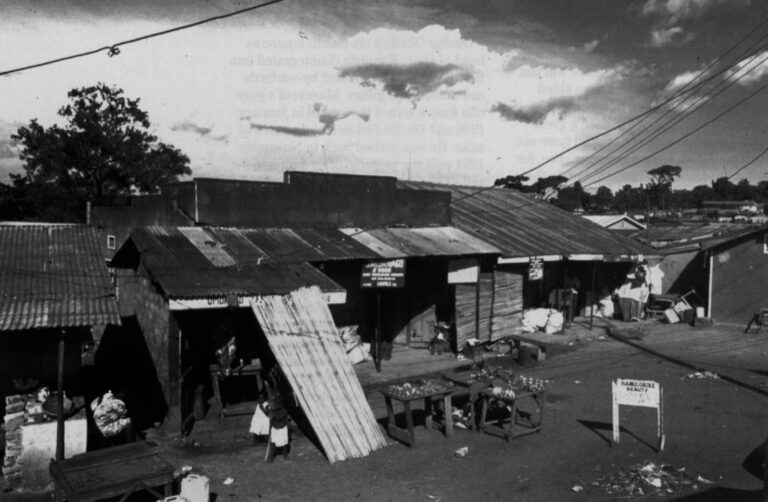

Most Ugandans are living in peace. The economy is picking up. Roads have been repaved. Refugees have returned. Hospitals and schools have reopened. An independent press is flourishing, and other independent civic and political associations are emerging. A Constitution is being debated, and Parliamentary elections are scheduled for next year. People walk the streets at night without fear of soldiers or criminals. Ugandans are living with hope.

“Let’s agree on the essential points,” Museveni told me, “Regular elections, universal franchise, free press, separation of powers.”

But for all this good news, Ugandans remain sharply polarized along ethnic and regional lines. After Museveni’s guerrilla forces took power in 1986, in a continuation of the cycle of fighting that had consumed the country since independence from Britain in 1962, remnants of Tito Okello’s defeated UNLA army went back into the bush in northern Uganda and waged yet another guerrilla campaign. Museveni’s forces have been battling a succession of insurgencies in the north ever since, by turns crushing and co-opting the insurgents and their presumed supporters. Though army abuses have not been on a scale comparable with those that occurred under previous regimes, hundreds of thousands of civilians have been displaced from their homes, and not a few have been killed.

Uganda’s continued polarization is worrisome not just because of the legacy of past ethnic conflict but because of the continued absence or weakness of the mediating institutions of civil society. Amin and Obote destroyed the rule of law in Uganda. Police, courts, the army — all were either politicized along ethnic lines or eviscerated. The law of the jungle obtained — the rule of the gun.

For years state crimes went unpunished. And in the absence of individual accountability for these crimes, groups were blamed –and groups were relied upon to achieve justice.

President Museveni, to his credit, has made it a priority to reestablish the rule of law. He virtually scrapped the discredited police force he inherited in 1986 and has hired and trained a new one. He is rebuilding a cowed and withered judiciary with the help of western aide — he told me their were only “three or four” high court justices left in the entire country when he came to power. He has also worked to diversify and professionalize the army. By all accounts (except in the north), the progress on these fronts has been remarkable. But there is still a long way to go, and abuses still occur.

Meanwhile, there remains the dicey problem of legal accountability for the many heinous crimes committed under past regimes. Uganda’s attempts to confront its ugly past have been disappointing. One of Museveni’s first acts when he came to power in 1986 was to establish a Human Rights Commission to document the country’s history of abuses and, it was hoped, identify and prosecute the culprits. The aim was to clearly identify his regime as a “break from the past.” Eight years later the Commission’s findings have yet to be published, and very few individuals have been successfully prosecuted.

There were logistical problems. Money and resources were limited. Evidence was poor. The continuing fragility and incompetence of the law undermined efforts to successfully prosecute even those individuals whom the Human Rights Commission recommended prosecuting. A few prominent individuals were arrested and tried, only to be acquitted for lack of sufficient evidence. These failures discredited the process and discouraged witnesses.

But the main problem was political. Inevitably, past regimes were closely identified with different regions and tribes; going after accused human rights abusers was perceived in those regions as persecuting their tribes. In some instances communities refused to cooperate with investigators, shielding criminals in their midst on grounds of ethnic solidarity. And there was concern that so many people had blood on their hands that settling accounts would be impossible. “Where will it end?” I was told.

The recurring insurgencies in the north also created problems. Many northern insurgents, ex-Obote fighters, were motivated by fear that they would be brought to accounts by a government dominated by southerners. In 1987 a general amnesty was declared in hopes of luring northern rebels out of the bush. This was Museveni’s strategy of “buying peace.” He offered rebels a chance to come out of the bush and be integrated into the national army. Many took it. “We thought that trying to punish everybody — it would be an endless process,” Museveni told me.

(Photo by Mary Jane Camejo)

The downside, of course, is that a great many people — Tito Okello among them — have never had to answer for their crimes. “A government has given an amnesty, but the people against whom these crimes have been committed didn’t give that amnesty — the people have not forgiven them,” said Joan Kakwenziri, a historian at Makerere University in Kampala who is a member of the Human Rights Commission. “Amnesty is really a just a cover-up of the problem. It’s like pushing dirt and dust under the rug. Eventually it begins to smell. It doesn’t work.”

Justice Arthur Oder, who chairs the Commission, underscored the dilemma Uganda faces in balancing the need to punish and the need to reconcile. “As a judge, I believe that the law should take its course, but in the final analysis the decision is political. Between politics and law — it is a difficult choice, but they are intertwined. To have reconciliation, you may have to sacrifice certain principles, like justice. On the other hand, punishing individuals may be an instrument for building a civil society.”

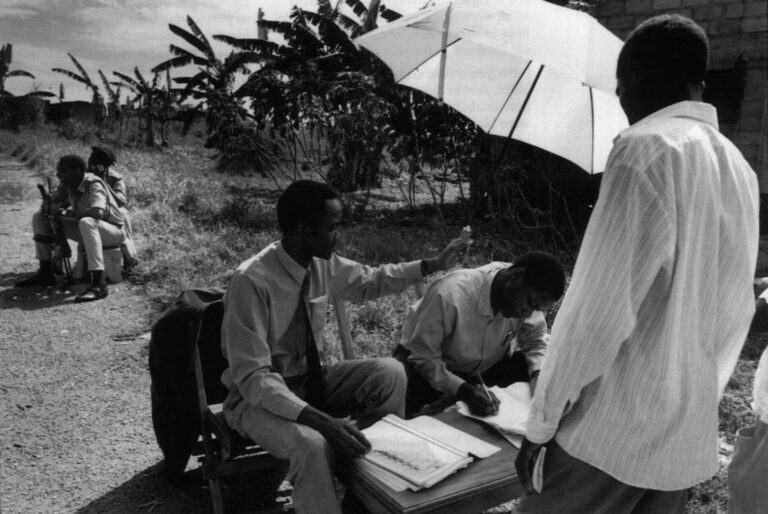

“Buying peace” has deprived Ugandans of the kind of official records that could have emerged from systematic Nuremburg-style prosecutions. The country lacks a common version of its own history. People living in different regions of Uganda know little of what occurred in other regions, and they are vulnerable to the machinations of revisionist historians such as Amos Kjube, Editor of “The People” newspaper, a mouthpiece for the Milton Obote’s old Uganda Peoples’ Congress. Earlier this year, Kjube published a series of articles purporting to prove that in fact Museveni’s forces –not those under Obote and Tito Okello — were responsible for most of the 300,000 civilian deaths in Luwero triangle during the early 1980s. “There is no way the NRA could have defeated the UNLA if they didn’t kill more people,” Kjube told me.

(Photo by Mary Jane Camejo)

In fact, the NRA did kill many civilians in Luwero — accused collaborators, government agents and such. The NRA did engage in psychological warfare, deploying “agents provocateurs” to commit atrocities that would alienate communities from the government.

In the flurry of charges and countercharges, people are free to believe what the want to believe, or believe what others want them to believe. And if all sides are to blame, no one is to blame. In the meantime, the NRM has had its own crimes to answer for in the north. Observed Joan Kakwenziri: “I think they feel quite inadequate to be the judges.”

@1994 Bill Berkeley

Bill Berkeley, a freelance writer from New York City, is investigating ethnic conflict in Africa.