In 1983, leaders of the CIA-financed Nicaraguan contra army ordered the detention of four field officers accused of insubordination, graft and murder. Argentine and Honduran military officers interrogated the detained, and then the rebel general staff ordered them executed. With dozens of rebel fighters looking on, the men were strangled to death and their bodies burned and buried in a clandestine Honduran gravesite.

Rebel officials acknowledged the killings at the time, portraying them as military executions rather than as common murder and suggesting that they demonstrated rebel commitment to principles of law and the norms of military justice.

A CIA agent working with the contras also acknowledged the executions, saying they followed a “court-martial” of the accused rebel officers. But details of how the men died have never been known publicly.

Now rebel witnesses have for the first time provided a careful account of the execution, an important early glimpse into what U.S. and rebel officials considered acceptable military punishment within the CIA-financed movement. The details suggest that the forms and procedures used in the September, 1983 executions strikingly resemble the death-squad-style slayings which human rights organizations have long attributed to the contras-but which rebel officials have always denied.

The contra officer designated to oversee the executions was Jose Benito “Mack” Bravo. The choice was significant. Accusations of murder and brutality accumulated throughout the eight-year conflict against Mack, a former National Guard sergeant. Yet perhaps because of his close ties to Enrique Bermudez, the former Nicaraguan National Guard colonel recruited by the CIA as the rebels’ “supreme commander,” Mack was never punished for any of his abuses.

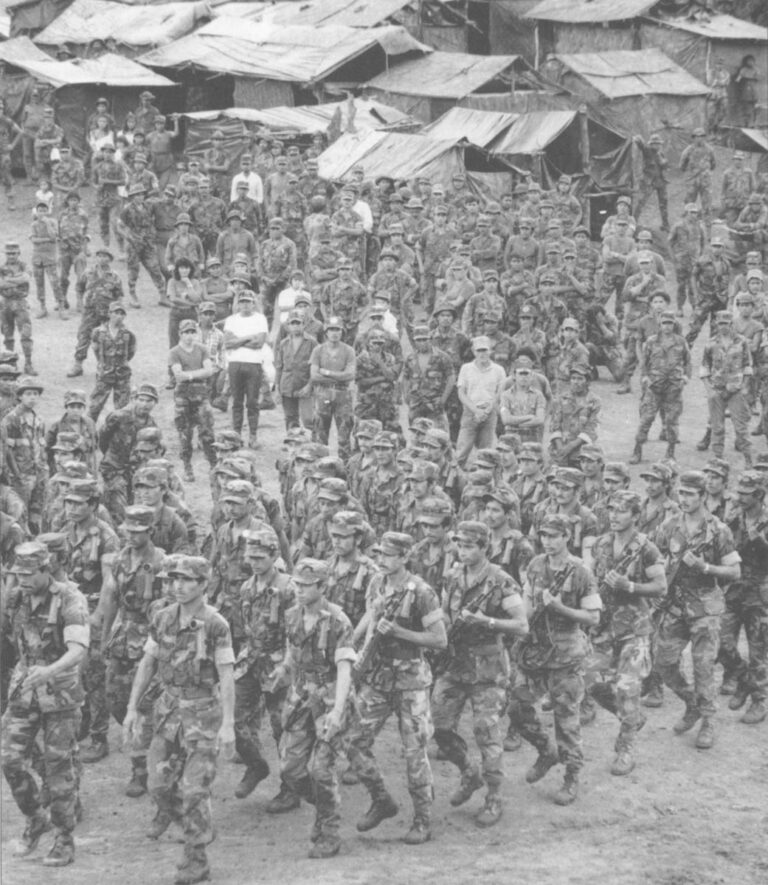

Mack rose to head the contras’ main U.S.-financed contra infantry training base in Honduras and, in 1988, became the contras’ top intelligence officer. During a sweeping investigation of suspected Sandinista infiltrators into contra ranks carried out in fall 1988, dozens of contra fighters were tortured and raped, and one young rebel was beaten to death. Mack was supervising the brutal investigation, and under intense pressure from U.S. officials, a contra tribunal convicted Mack of covering up the murder. As a result, Mack was briefly suspended from the rebel force. But three months after his conviction, with the war over and the contra army facing demobilization, Bermudez reinstated Mack to his intelligence post–a post he still holds.

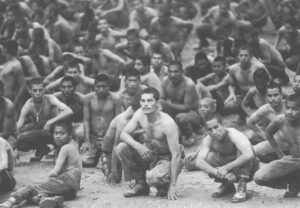

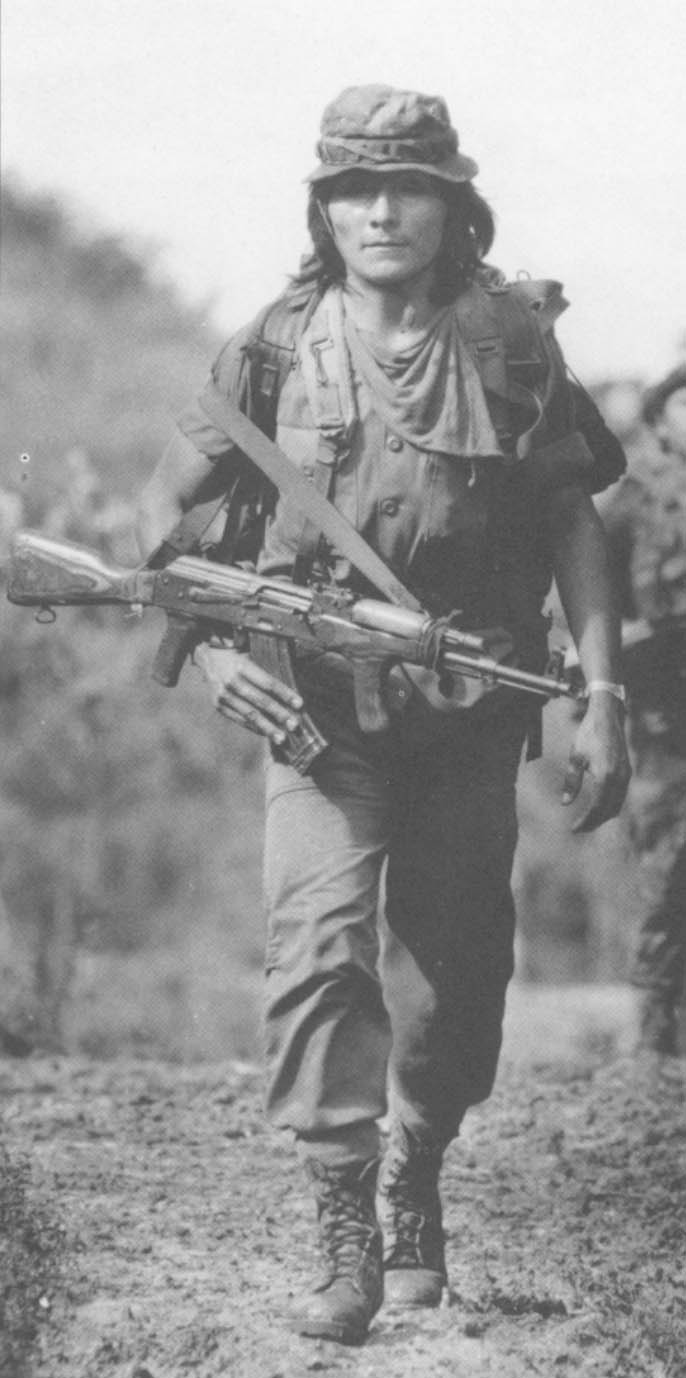

A dark-eyed peasant from the central Nicaraguan province of Chontales, Mack joined the National Guard during the 1950s, when he was a teenager. In his early career, he became dictator Anastasio Somoza’s personal house-boy. Eventually he scrapped his way up to sergeant, only to have his life fall apart, at age 35 in 1979, when the Sandinista revolutionaries defeated the National Guard. In exile, first in Guatemala, then in Honduras, Mack became one of the first contras, training rebel Miskito Indians when CIA funds first began to flow to the rebels in 1981. Later, Bermudez made Mack commander of the La Lodosa training base in Honduras’s pine-covered mountains near the Nicaraguan border.

At La Lodosa, Mack’s brutality flourished, according to rebel fighters and officials who served under him. A Nicaraguan doctor now living in Miami, then 27 years old, set up a CIA-financed clinic in La Lodosa in 1983. He learned of a dozen murders in Mack’s camp during one two-month period alone.

Mack had surrounded himself with angry ex-Guardsmen, men not only paranoid about Sandinista infiltration but who killed for lust, men whose weapons of choice were wire for strangling and heavy knives for slashing. In one case, Mack’s men captured three Sandinista peasants in Honduras, a 40-year-old father, his son, and a nephew, both about 20. Mack’s men accused them as Sandinista spies, lashed them to a tree, and beat them bloody. There was no “interrogation,” the Nicaraguan doctor recalled, Mack’s men “just took advantage of the opportunity” to torment the prisoners. The next morning, the prisoners were gone. Mack told the young physician they’d been sent back to Nicaragua. But three days later, a dog began clawing the ground near the clinic. It dug up a human foot. Investigating, the doctor discovered the three men’s bodies. They’d been hung. Mack ordered rebel fighters to rebury the men, and told the doctor to keep quiet about the case.

One of Mack’s most vicious killers was Jose Espinales, known as “Zero-Three,” a muscular, 29-year-old former National Guard police sergeant. After the doctor discovered several murders Zero-Three had committed at La Lodosa, Zero-Three turned on the physician himself. The doctor fled the camp, reporting the assassinations to Col. Bermudez and other rebel officials. Nothing was done to Mack. Another assassin was “X-Seven,” a former Guard private. Another was Ramon Pena Rodriguez, “Z-Two,” a 45-year-old former National Guard police corporal who, as Mack’s “intelligence officer” interrogated screaming prisoners on a hill overlooking the La Lodosa camp. By fall, 1983, Mack had two base camps. Adjacent to both were clandestine graveyards.

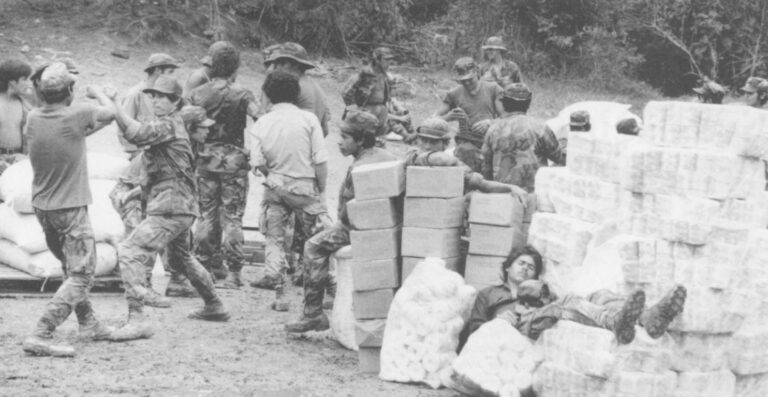

The violence that unfolded at Mack’s bases was not unique. Numerous rebel fighters have described extensive violence at each of the half dozen or so CIA-financed rebel base camps scattered along 250 miles of Honduras’ pine-forested border with Nicaragua. All the remote camps, without exception, were commanded by ex-Guards entrusted with life-and-death power over hundreds of rebel fighters.

There were murders of prisoners and recruits, murders of suspected spies and confirmed rivals, murders of rejected lovers and personal enemies.

Beyond the bloody, casual violence that surrounded the contra camps, however, rebel agents were ordered to participate in formal death squads that cooperated with Honduran authorities from 1981through 1984 in an anti-leftist extermination drive, according to a high-ranking former rebel officer who enjoyed access to rebel intelligence and counterintelligence files in a Tegucigalpa safehouse from 1981 through 1985.

According to the former rebel officer, Honduran and Argentine officers identified targets–mostly leftist Honduran student and union leaders–and contra hitmen carried out the killings. The contra officer said that the contra death squad arrangement was forged in a 1981 meeting between Col. Gustavo Alvarez, then chief of the Honduran security forces, Col. Jose Hoyas, an Argentine military adviser to the contras, and former Nicaraguan National Guard Maj. Emilio Echaverry, then the rebels’ chief of staff. After working out an agreement over the general concept, Alvarez turned coordination of Honduras’ participation over to an aide, then-Captain Alexander Hernandez. Echaverry and contra commander Bermudez turned contra coordination over to the rebel intelligence chief, ex-Guard Col. Ricardo Lau.

The rebel officer’s details amplify charges by the New York-based Americas Watch and other human rights monitors, who have also accused the contras as the triggermen in death squads orchestrated by the Honduran military. A 1987 Americas Watch report detailed the extensive evidence suggesting that contra henchmen executed Honduran leftist and other detainees turned over to them by the Honduran military during the period of mass Honduran disappearances, 1981 through 1984. Americas Watch also identified Capt. Hernandez as the Honduran military officer supervising the death squads.

One inside glimpse into the workings of the contra death squads came in 1986, when a former Nicaraguan rebel who said he was a member of a contra death squad described to a reporter for the Progressive magazine how Capt. Hernandez called him in 1982 to arrange the murder of two leftist student leaders. The contra described how he picked up the two detainees from a Honduran military jeep on a highway near Tegucigalpa, drove them south of the capital, dug a grave, and stabbed them to death.

In August, 1983, during a Nicaraguan army cross-border attack on Mack’s Honduran base camp, Sandinista troops captured an attaché case, full of documents that Mack had abandoned. Among the captured papers were photos of Mack with Argentine advisers, canceled receipts for gasoline, a letter received from his wife in Miami, and a small personal telephone list. It included a number for an interesting contact: Capt. Hernandez. Little other direct evidence ties Mack to other death squad activity coordinated with the Honduran authorities, but the routine manner in which he orchestrated the complicated September 1983 execution of three contra officers, on short notice, suggests striking similarities with the modus operandi linked to these squads. That’s why the 1983 killings provide an interesting case to study in detail.

The three prisoners executed were themselves rebel officers and, like Mack, ex-Guardsmen. One was Julio Cesar Herrera, 28, whose pseudonym was “Krill.” The other two are remembered only by their war names, “Cara de Malo” and “Habakuk.” The three had all been staff officers to Pedro Ortiz Centeno, the ex-Guard sergeant-turned-contra-commander known as “Suicide” who, posthumously, became one of the most famous insurgent field commanders after Washington Post correspondent Chris Dickey chronicled his rebel career in his book, With the Contras (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1985.)

Suicide and his three staff officers were accused of three crimes: the first, ironically, was that they had committed dozens of their own camp murders, with Krill alone killing more than 30 contra recruits over a period of months. The joint command of Honduran, Argentine, Nicaraguan and CIA officers then administering the war appeared even more upset about accusations of Suicide’s involvement in embezzling contra funds by padding payrolls and even, perhaps, selling weapons to Salvadoran guerrillas. Most serious to the contra leadership, however, was that Suicide and his men had challenged their authority. The last straw came when Suicide, clutching an M60 machine-gun, led his men in a brief seizure of the Tegucigalpa safehouse where the general staff was living. That frightened everyone.

For all this, top rebel leaders decided to set an example to other contra units. Suicide and his men were seized and held under extremely tight security, bound and confined for about a week in separate closets in an old farmhouse at La Quinta, an abandoned farm on Tegucigalpa’s western outskirts that in 1983 served as an insurgent training installation and offices for the general staff. Rebel special forces troops who guarded the four detainees later described how nervous Argentine officers at La Quinta ordered them to train their assault rifles, safeties off, on the prisoners every second when they were let out to go to the bathroom.

A CIA officer working with the contras at the time told then-contra spokesman Edgar Chamorro that Suicide and his men were “court-martialed” by a panel of ex-Guardsmen before their executions. But contra officers today express doubts that there was ever any such formality. Several accounts circulate of the execution of Suicide himself, but no eye-witness has ever stepped forward to confirm details. There were, however, plenty of eyewitnesses to the executions of Habakuk, Cara de Malo and Krill.

Those who watched would never forget.

The episode began with a radio message from the rebel general staff to Mack at La Lodosa, according to Marlon Blandon, a former Guard lieutenant now living in Miami who was Mack’s executive officer at the time and witnessed the executions. The general staff wanted to see Mack in Tegucigalpa.

With Blandon, his bodyguard and driver, Mack drove 80 miles west to the Honduran capital, finally pulling his U.S.-supplied yellow Toyota Land Cruiser into La Quinta. Mack’s aides waited in an outer room as he entered the offices to meet with the rebel general staff. About an hour later, Mack emerged with his orders.

From La Quinta, Mack radioed to Zero-Three out at La Lodosa, telling him to march with about 40 soldiers to an agreed-upon meeting place in the border mountains. Bring some picks and shovels, Mack said.

A Toyota Land Cruiser was brought up to the farm house at La Quinta, and the three blindfolded prisoners, Krill, Cara de Malo and Habakuk, were dragged out. Their wrists were handcuffed and their feet bound with rope. They could barely walk. Blandon said he believed they’d already been tortured, but that wasn’t clear, because of another problem: their mouths and noses had been bound tightly with adhesive tape, so breathing was nearly impossible. They were gagging.

Rodolfo Robles, a civilian accountant who had been a police informer under Somoza and worked in the contra army’s logistics department, shoved them into the back of the Land Cruiser. They were forced to lie down.

It was past dark by the time the rebel vehicles headed out for the border, driving in a virtual convoy: Mack and his aides in the lead Toyota, Capt. Leonel Luque, a liaison officer from the Honduran army in the second, the prisoners in a third, Robles in a fourth. A couple of other jeeps filled with contras followed.

After a 90-minute drive, the convoy reached Danli, a cowboy town 25 miles from the Nicaraguan border, where Robles pulled into a service station to buy gasoline in a portable container. Then the convoy drove five miles south through the town of El Paraiso, then some 15 miles further, across the Choluteca River, towards the village of Alauca. The jeeps finally pulled off the dirt road onto a mule trail. It was about 1 a.m.

Mack’s ex-Guardsmen were waiting: Zero-Three, X-Seven, Z-Two. As the rebels climbed out of their jeeps into the chill of the mountain air, Capt. Luque, the Honduran liaison officer, asked Mack if they were close to the Nicaraguan border. His orders, he said, were to bury the prisoners inside Nicaragua. But Mack said that was a full day’s march away. Luque relented.

There were no Honduran farms nearby, and the mule trail was little used. But Mack ordered his men to set up a security perimeter anyway, to order off any peasant that might chance by.

Capt. Luque gave the order for three graves to be dug, and Mack’s men set to it with picks and shovels about 10 yards off the trail. It was rocky soil, and the digging was tough. After at least an hour of grunting, the graves were only four feet deep. But Capt. Luque was impatient. He gave his OK.

“It’s time,” he said. “It’s late.”

There were several dozen contra fighters ringing the jeeps, standing silent in the night air. The prisoners were lying motionless in the Land Cruiser. Two of Mack’s contras opened the rear door, grabbing Habakuk first. They pulled him out like a sack of potatoes, and it wasn’t clear to witnesses how much life was left in him after the hours of gagging from the tape. He fell to the ground. When the contras pulled him to his feet, still bound, Robles came up behind him, tossed a length of rope around his neck, and yanked it tight. There was no noise. Robles said nothing. It took less than a minute.

When Robles released his grip, Habakuk fell limp to the ground. Two contras dragged him by his boots to the edge of one of the graves.

Cara de Malo was next, and it was much the same story. The prisoner couldn’t stand. When X-Seven pulled the rope tight around his neck, it was over quickly.

That left Krill. And as it turned out, Krill was still very conscious. Probably the tape over his nose and mouth was looser, because when the Toyota door opened, he heaved out a haunting plea that, if muffled, nevertheless rang through the night silence, stunning everyone. His words were just comprehensible.

“Shoot me, please, don’t stab me. Don’t make me suffer!” Krill pled.

“That’s what I always remembered when it was over,” said Lt. Blandon, the rebel aide to Mack who recalled the execution. “I’ve heard him say that again and again in the years since.”

Nobody responded. Instead, Krill was yanked from the jeep. Zero-Three hit him from the rear with the cord. Krill’s body slumped after about a minute’s worth of strangling. Two contras began dragging him through the underbrush toward the yawning grave.

Then one of the rebel officers burst out: “Hey! Wait! He’s still alive!” It was true, Krill was gasping for air, wheezing through the crumpled tape. “Please don’t kill me in this way!” Krill mumbled.

X-Seven shoved Zero-Three aside to climb on top of Krill, planting his knee on the prisoner’s chest and curling the cord tight again. After a longer time, Krill was completely limp. X-Seven climbed back to his feet.

But as the gravediggers began dragging Krill toward the pit again, the gasping sobs came back. Krill’s rib cage was heaving up and down.

“You son-of-a-bitch!” grunted X-Seven. “We’ll see if you survive this one!” He hurled himself back on top of Krill’s prostrate body, by now face down in the dirt. This time the former Guard seized Krill’s head with his bare hands, twisting it violently upwards and backwards, until Krill was practically looking straight backward, his spine apparently shattered. Finally, Krill was dead. The struggle had lasted at least 20 minutes.

At Capt. Luque’s direction, the gravediggers stripped the three rebel bodies of their handcuffs and boots, then slashed the bottoms of their feet with knives. Luque claimed this would permit the bodies to burn more completely. Then the bodies were pitched into the graves. Somebody fetched the can of gas from Robles’ jeep, and they were thoroughly doused. Ignited, the bodies burned like three torches for more than an hour in the Honduran night.

Then the smoking ashes were covered over. It was nearly 5 a.m. by the time Mack and his aides pulled out.

On the drive up to La Lodosa, higher in the mountains, Mack told Blandon that the general staff had ordered him to carry out the executions in front of his men so that they would learn, by example, the consequences of defying the central command.

©1990 Samuel Dillon

Samuel Dillon, on leave from the Miami Herald, is exploring the roots of Nicaragua’s contra war.