The death of Daniel Teller in a 1983 contra ambush deeply shook colleagues throughout the Sandinista Front. He’d proven himself to be one of Nicaragua’s most brilliant and promising young political cadres.

During four years of revolutionary work in northern Jinotega province, Teller led the transformation of the Sandinistas’ guerrilla columns into regular army battalions, forged a Marxist strategy for backwoods class struggle, and pioneered the Revolution’s political approach to counterinsurgency war.

Teller’s work was meticulous, and despite his own middle-class origins, he sought to develop friendly bonds with Jinotega’s farmers. But the revolution’s collectivization and agrarian transformation policies infuriated many northern hill people, and Teller’s career unfolded against the ominous backdrop of peasant rebellion.

By 1982, dozens of CIA agents across the northern border in Honduras were working hard themselves to train and arm a counterrevolutionary army. Their efforts bore fruit, and in May 1983, a 160-man contra task force, newly-armed with U.S. weapons and operating under the command of a former National Guardsman schooled at West Point, marched down from a mountain redoubt and seized the main highway linking Jinotega’s provincial capital with border villages. Teller drove his jeep into the ambush and died in combat.

Teller had built a reputation for caution in his rural political work, and his death dramatized the contras’ alarming new strength, and the vulnerability of even high-ranking Sandinista cadres working all across frontier Nicaragua. Teller’s father was a middle-class engineer; Daniel was the fourth and last child. He was one of hundreds of middle-class teenagers who began collaborating with the Sandinista Front as a teenager; he was 13 when he began running messages between safe houses past the Guardia checkpoints. Teller went to a Catholic high school, then began studying architecture at the University. But the Sandinista-led insurrection was building, and he dropped out to fight. His developing intellect and bravery earned him quick recognition within the Front, and within weeks of their July 1979 triumph, the comandantes in Managua dispatched Teller as military commander to Jinotega, 100 miles north of Managua. The capital of a vast province, Jinotega was a market town of coffee growers and beef ranchers nestled in the shadow of timber-covered hills.

Teller was just 19, with a teenager’s face, when he arrived. His youth shocked many Jinotegans. “This is just a kid, with incredible responsibilities,” was the common reaction, a Sandinista colleague, Alonso Porras–today Nicaragua’s agrarian reform chief–recalled later.

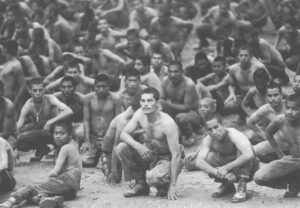

Teller found chaos in the military. There was no logistical system yet, and the guerrilla troops of the Sandinistas’ northern columns were camped on the hillsides. Food rations were intermittent. In Jinotega’s frigid northern climate, many troops didn’t even have ponchos. The troops were drinking. There were abuses. Worse, the guerrilla chiefs who had inherited command at the triumph had moved themselves into a mansion on the city’s outskirts, confiscated from a wealthy coffee farmer who had fled to Miami, and were celebrating their victory with a series of wild debauches.

Teller was fascinated with military theory and was developing a collection of sidearms and exotic automatic rifles. So, despite his youth, Teller was already a soldier’s soldier, and he imposed order. He demanded discipline from his officers, and moved, personally, out onto the hillside in a tent with his men. Then he began battling the fledgling Sandinista bureaucracy to get resources for the troops.

Within a few months, the effort to transform the ragtag columns into Nicaragua’s new regular forces began in earnest, and the regional command called Teller back to Matagalpa, 20 miles to the south, and ordered him to organize the first regional battalion. But the Sandinista Front had not fought its war merely to reshuffle Nicaragua’s state apparatus. The agenda called for radical transformation, and as soon as Teller had established a skeletal regional military administration, his superiors sent him back north to join the organizing for social revolution.

These were times of extraordinary exhilaration for the young revolutionaries, and many of the cadres were expressing it sexually. Teller himself raised eyebrows when he decided to marry a girl named Marta Veronica, a ravishing, if barely pubescent companera he met while overseeing Jinotega’s Sandinista Youth. The organization’s leaders objected, it wasn’t correct, Marta was too young, they said. But Teller insisted, and they realized he himself was barely post-adolescent, so it seemed OK for him to marry a young girl.

Teller’s first revolutionary task was to organize Jinotega’s “working class”–18,000 coffee workers and cowhands–into the Sandinistas’ new Rural Workers Union, the ATC. Teller had been in the Sandinista Front long enough to ground himself thoroughly in Marxist theory, and he exhibited a youthful confidence that its methodology held the answer to Jinotega’s injustices.

“There’s no need for more theory,” he told subordinates in the ATC. “There’s Carlos Fonseca, Sandinismo, books, documents–the scientific theory is clear. Here the thing is to WORK, to put the words into practice.”

Teller wasn’t from Jinotega, but as he saw it, the province’s people fit well into Marxist categories. He sensed a contradiction between the province’s large coffee growers and cattle ranchers and the rest of the population. The revolutionary task was to organize the “agricultural workers” into farm unions, the “peasants” into production cooperatives, the “semi-proletarians” into collective forms of production, and medium-sized farmers into credit and service cooperatives.

He spent a few days with his staff studying Jinotega’s history, concentrating on the periodic conflicts between peasant workers and large farmers. Then they began to mark up the provincial maps, pencilling in some peasant communities and large farms for agitation. He worked closely with Oswaldo Loasiga, a peasant who had fought with Omar Cabezas’s guerrilla column. Loasiga knew Jinotega’s peasants like his own family, and Teller, together with Loasiga, systematically visited all those who had collaborated with the Sandinistas during the insurrection. Teller compiled a human inventory of potential leaders.

He taught his staff Marxist theory, as well as the nuts and bolts of organizing: how to make reports, to draw up organizational documents, to lead a meeting. Driving his jeep with his ATC staff into remote mountain areas, he was teaching his people how to analyze the population and its class composition, how to detect militant leaders.

Unlike many Sandinista leaders, who wielded their new revolutionary powers roughly, patronizingly, Teller, despite his urban background, found common ground. He would show up in a remote village to go shooting, to hunt deer with the companeros, to see some peasant’s new dog, the whole deer-hunting thing. Sometimes he’d carry farmers he was wooing out to a lake for duck-hunting.

Teller’s ATC organizing brought dramatic numerical results: in four years, the organization grew to include 14,500 of the province’s 18,000 rural workers. Many of the province’s coffee pickers and other workers were enthusiastic about the Revolution.

But after just one post-revolution harvest, large numbers of other northern farmers were already profoundly uneasy with Sandinista ways. As they saw it, even if the Guardia had been repressive and corrupt, Somoza’s Nicaragua had rewarded hard work with largely stable and independent lives.

Consider the landless peasants Teller called “semi-proletarians,” for instance. Before the revolution, renting crop and pasture land at generally reasonable prices from large landowners, many had forged adequate, if minimal, standards of living. With the triumph, the Sandinistas confiscated the lands of the largest ranchers, and in many cases, the former tenants were physically removed to ATC-run cooperatives. There they were expected to farm collectively, under the direction of Sandinista administrators.

In the same way, those who had been wage laborers on the Somoza-era haciendas found themselves working for new revolutionary administrators telling them that the lands were now “theirs.” This was a popular idea, because the peasants–accustomed to seeing their padrones wintering in Miami–assumed they’d get a slice of the farm profits they knew could make the good life possible. But they soon found that the new padron, the Agrarian Reform Ministry, was only marginally more generous than the last. And under inexperienced new managers–despite revolutionary rhetoric about better wages and conditions–workers watched “their” haciendas crumble into disrepair and confusion.

During the 1980 planting season many of the thousands of small, independent farmers were infuriated when Sandinista banks withheld credit to those refusing to join Sandinista co-ops. Gas stations were refusing to sell gas to those without a co-op card. Farmers were forced to sell their basic grains and coffee to the government monopolies, Enabas and Encafe–and they were paying farmers well below market prices for their crops.

By late 1980, mini-rebellions were breaking out across northern Nicaragua. The first, and most famous, came in July when Pedro Joaquin Gonzalez, a disgruntled Sandinista commander in the town of Quilali deserted, secretly trained an 80-man peasant band for a month, then briefly seized the town he had previously commanded. By September, another group of peasant rebels had gathered on the slopes of Kilambe mountain to the east. Sandinista army sweeps quickly crushed these two rebellions. But a third group had taken to the northern hills under the command of Encarnacion Baldivia, “Tigrillo,” a sharecropper who’d been a Sandinista soldier. Illiterate, Baldivia nonetheless had a shrewd intelligence and a persuasive speaking style–and he had dozens of cousins who were rankling under the Sandinistas’ patronizing ways just as he was.

“According to their politics, all of us Nicaraguans were real backward, real brutes, and so they sent ‘Cuban friends of ours’ to teach us all how to live,” Baldivia recalled later. “They acted like they were our new little fathers. That attitude didn’t sit well with me,” Baldivia recalled.

At the time of Baldivia’s first attack in late 1980, he commanded just nine men. Six months later his ranks had grown to 30. Though he was fighting with no outside help, he was proving that the remote northern farmsteads were fertile recruiting grounds for an anti-Sandinista guerrilla force. The Sandinistas knew from the intelligence reports arriving from the exile refugee camps in southern Honduras that the Reagan Administration was moving to take advantage. After Baldivia ambushed a jeep near El Cua in June 1981, killing seven Sandinista officers, the Managua leadership decided to send an elite combat brigade to the zone to test various tactics for fighting the counterrevolutionary enemy.

The leaders dispatched Teller to represent the Sandinista Front on its general staff. In El Cua, Teller and the rest of the Brigade encountered a hostile population; the revolutionaries began to feel for the first time like an occupying force.

“When we came, we didn’t trust in anybody, we saw in every person a potential ‘chilote’ (rebel). It wasn’t safe to trust anybody,” wrote Armando Zepeda, a Sandinista who worked with Teller there.

Teller’s first steps were obvious. There were government officials in El Cua who were inefficient and arrogant, and he got a bunch of them sacked early on. Finding consistent delays in deliveries of food and other supplies, Teller opened battle with bureaucrats back in the provincial capital.

But more important, Teller brought to the spreading war the same painstaking political research he’d applied to his revolutionary organizing. He understood the importance that careful study of the peasantry would play in the course of the conflict.

Teller organized a series of censuses and military reconnaissance missions into the surrounding hills, a micro-regional intelligence study aimed at answering the key questions: Who were the contras’ collaborators and why? What were the contras operating procedures, their routes through the mountains, their logistical practices? As the intelligence poured in, Teller struck on a tactic that was to become central to the Sandinistas’ way of waging war. He saw that Tigrillo’s people were moving through the hills along established corridors, stopping for food and to gather information at friendly farms along the way. Teller conceived the idea of establishing “self-defense” cooperatives along these routes.

“If we know that a given village is a crossroads for the Somocista gangs, political work is directed at the peasantry there to persuade them to group together for defense–or we apply the agrarian reform and OUR peasants are located there, with their weapons, in what constitute territorial military units,” a Sandinista colleague later wrote of the tactic Teller conceived.

Within a few months, the Brigade’s political work had helped to stabilize El Cua, and in 1982, Teller moved back to the provincial capital to coordinate application of the same approach in other northern war zones. But if the self-defense co-ops were impeding the contras’ movement, the rebel forces were causing severe problems of their own. Production on the state farms was plummeting as the tillers marched off for militia duty. Even so, the militias were having difficulties repelling rebel attacks. Over the course of the year, CIA funds poured into the contra organization effort, and the early, independent rebel groups Teller had been fighting were replaced by larger well-armed rebel units infiltrating down into Jinotega from Honduras.

Teller understood the building threat to the revolution, personally. His friend Loasiga, the peasant who had introduced him to all the historic Sandinista collaborators, died in a road ambush. He began to worry about his other staff people. One day in April, 1983, Teller passed by the office of Arquimedes Rivera, an old friend he’d recruited as a union leader. “He left me a piece of paper,” Rivera recalled. “Let me make a recommendation. When you go out, request information about the situation. Ask State Security. If it’s dangerous, don’t move,” Teller wrote Rivera. “With a cadre like you, we’re not going to be able to replace you immediately. Be careful, OK?”

It was a cautious procedure Teller followed himself. May 1, 1983, Teller was to drive to a meeting in Wiwili with three bodyguards, in his red jeep. He checked in with counterintelligence before leaving Jinotega, and again, 20 miles north at the zonal office in Pantasma. There, he was told a Sandinista army company was in control of the highway north to Wiwili. No problem.

In reality, the army company had withdrawn the night before, and nobody knew. Minutes after Teller left Pantasma, a soldier burst in to the Pantasma zonal office to report combat on the highway. Stunned, the Pantasma Sandinistas rushed to follow and warn Teller. But they lost 20 minutes looking for a vehicle.

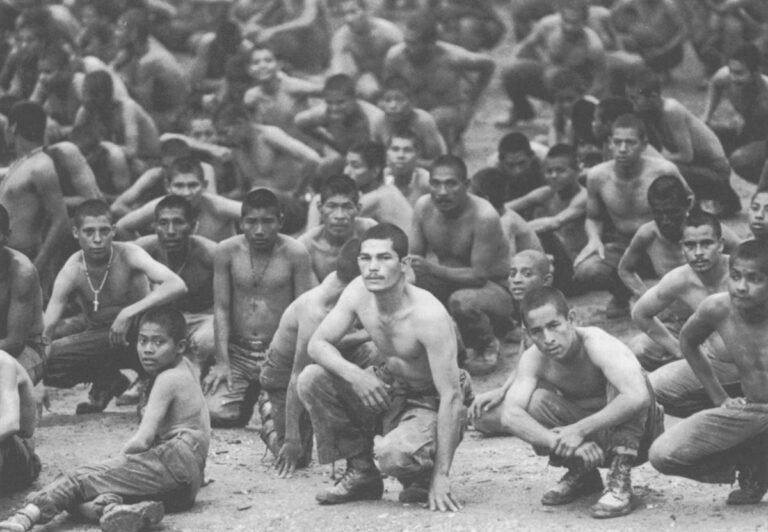

A group of contras from the Diriangen Task Force, under the command of Oscar “Ruben” Sobalvarro had mounted an ambush at the place called Zompopera. They were 160 men, heavily-armed: they were carrying FAL assault rifles, plenty of grenades, and nearly a dozen M79 grenade launchers. It was a hot, sunny day, little wind. Ruben was emboldened by the size of his force.

His ambush was well-mounted: He picked a flat 200-meter stretch of highway cutting through a long, low hill, with curves at each end. The remains of the excavated hill formed walls at each side of the road, so there were no shoulders, no place to throw yourself once inside. Ruben ordered his men to pile stones in the center for a barricade. He numbered the ambushes’ key positions along stretches at each end and atop the rocky outcropping overlooking the road from one side. The way he set it all up, any driver on the road would round a curve and be trapped well inside before he knew it. By then there was nowhere to go.

The combat reported at Pantasma had been a truck that had driven south from the Wiwili side. It carried 13, including two West German doctors, several nurses, and some armed Sandinista soldiers. They’d blundered up to the barricade and had rejected contra shouts to surrender. All 13 died. Ruben’s men crept down from above to set the truck on fire and recover five M 16s, then returned to their positions to wait, hidden.

When Teller left Pantasma, that first ambush was already over-and there was no noise on the highway.

Just before Teller’s arrival at the ambush, a bus filled with Sandinista border patrolmen also drove down from Wiwili. When they got to within 70 meters of the barricade, they saw the burning truck and realized they could neither advance nor retreat. They leapt from the bus, but were completely dominated by the contra fire. Right at that moment, Teller’s jeep arrived at the other end. A contra nicknamed “Pony,” the squad leader hidden at the far end of the ambush, watched the jeep approach from Pantasma.

When Teller’s jeep entered the ambush zone, the border patrolmen, pinned down, couldn’t see what happened. But they said later that suddenly they heard fierce combat at the other end. By the thunderous fire, they thought reinforcements had arrived. They sensed that the contra pressure eased for a moment allowing them to race for better combat position. There, encouraged by the reinforcements, the border patrolmen began to shout revolutionary slogans. Then, from their new combat position they were able to see the other end; there were no reinforcements, just one red jeep.

Teller and his bodyguards had hurled themselves from their jeep, shooting, running, as the jeep careened on and hit the barricade. His three comrades were hit immediately, and then a bullet slammed into him, too. Wounded, he kept on running, looking for better combat position. Pony, the contra squad leader, saw Teller round the curve and race across the face of the opposite hill, some fifty meters away. “My people shot him, and he fell,” Pony recalled later. Minutes later, a contra raced across the road to recover Teller’s adjustable stock AK47. He also stripped him of his Seitz watch.

Three weeks after Teller’s death, the Sandinista Front posthumously decorated him with the Carlos Fonseca award–the revolution’s highest prize–for his pioneering revolutionary work. A surer sign that Teller’s legacy would live on however, came in the speech by Commandante Victor Tirado discussing the award. The government has confiscated from pro-contra farmers lands crossed by the rebels when mounting the Teller ambush, Tirado said. Self-defense co-ops, modeled on Teller’s ideas, would be established not on only those properties but in the future, throughout zones of contra sympathy throughout rural Nicaragua.

©1989 Samuel Dillon

Samuel Dillon, on leave from the Miami Herald, is investigating Nicaragua’s Contra war.