The October 1983 attack by U.S.-financed contra rebels on the northern Nicaraguan town of Pantasma was, militarily, a brilliant surprise strike, a classic town takeover, one of the few that the rebel forces ever achieved. It was also one of the single most destructive contra rampages in the entire seven-year war. Rebel troops razed an army garrison, police station, bank, sawmill, grain elevators, and a dozen government offices, burning several teachers alive in a rocket attack and executing prisoners before a massed crowd.

The Sandinista government called the attack a “massacre” and an “atrocity.” Busing hundreds of international visitors up from Managua to tour the town over the following years, government tour guides turned Pantasma into a premiere example of plunder and havoc that remained a symbol for the rest of the conflict.

Contra propagandists and the Americans financing and administering the rebel army, however, saw things differently. They saw Pantasma as a virtuoso performance.

The commander who led the attack was former Nicaraguan National Guard Lieutenant Luis Moreno, then a sandy-haired, baby-faced 24-year-old. Moreno’s father was the chauffeur for the administrator of dictator Anastasio Somoza’s sugar empire. At 17, Moreno had entered Somoza’s Military Academy. Intelligence and drive made him the top cadet in his class, and in 1978 he traveled to West Point on an annual exchange.

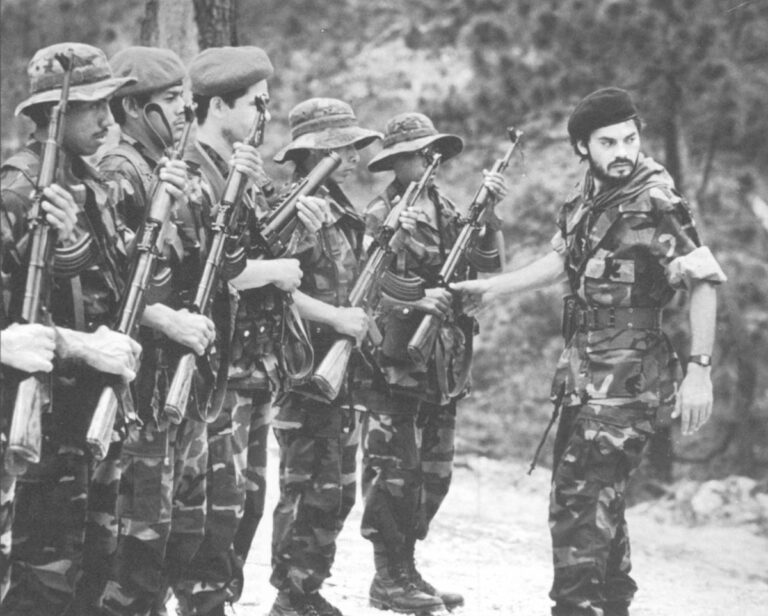

Back in Nicaragua during the final desperate weeks of the 1979 Sandinista insurrection, Somoza graduated Moreno’s class early, shoving the cadets into battle on a coastal highway. Wounded by shrapnel amid the final collapse, Lt. Moreno fell prisoner, broke free, took asylum in an embassy, and finally slipped out of Nicaragua and into three years of Central American exile. Then, starting in late 1981, the CIA began contacting former Guardsmen in efforts to build a rude officer corps for a counterrevolutionary force designed to confront the Sandinistas. Moreno signed on and took the nom-de-guerre “Mike Lima.”

As a contra, Mike Lima became one of the top rebel officers and one of’ the closest aides to the CIA-backed commander, Enrique Bermudez, himself a former Guard colonel, and a favorite of U.S. officials. In 1984, after Mike Lima lost his arm in a mortar accident in the Honduras base camps, U.S. officials flew Mike Lima to Washington, confined to a wheel-chair, for exhibit to lawmakers as a wounded “freedom fighter.”

“Highly regarded by his peers,” noted a glowing 1988 State Department profile of Mike Lima. In 1989, after the five Central American presidents called for the demobilization of the contra army, Mike Lima moved himself and his family to Miami. In a final press conference, he urged the American government to take responsibility for its Nicaraguan war by extending disability benefits to war wounded like himself. But even then, at the war’s end, Mike Lima looked back on his October 18, 1983 takeover of Pantasma as his highest achievement.

Throughout 1983, Mike Lima’s brand of warfare was exactly what the CIA had in mind for Nicaragua. CIA planners had assigned the vast farming region of lower Jinotega as his battle zone and his destructive campaigns closely reflected the Agency’s strategic dictates. Under the CIA’s 1983 campaign plan. Mike Lima was to maneuver through the zone, bloodying the enemy and destroying economic targets, especially farm machinery and road equipment. And he was to try to seize a town, even briefly, to publicize the mounting contra challenge to Sandinista rule.

Mike Lima carried out his marching orders in exuberant style. He named his task force the Diriangen, after an indigenous Nicaraguan warrior. He deployed his 400 men through valleys and ridges in a single, serpentine infantry column more than three miles long from point man to rear guard. Mike Lima himself, astride a white steed he’d rustled from a state farm, cantered alongside with a 30-man staff escort.

He came to love the burning of government trucks after a deadly ambush: the shattered glass, the blood on the pavement, the rush of flame.

By mid-year, Mike Lima had compiled a combat record–given the CIA’s strategy–that was the rebel army’s most distinguished. His campaigns were the most aggressive, his sabotage the most destructive, his ambushes the deadliest. His men, in jest, began calling him Napoleon. He just smiled.

By late September, however, he was short of supplies. For weeks, he had been radioing Honduras, calling for one of the new supply airdrops that the general staff had been promising. Finally, the drop had come: crates and crates of the wrong ammunition, shells for FAL rifles, while Mike Lima’s men were carrying AK47s. Nor were there any boots, nor cash to buy food.

Mike Lima decided to seize a town with a bank. Then he could buy supplies. In his operating zone, there were banks in only four towns: San Juan, Yali, San Rafael del Norte, or Pantasma. He marched his men in a vast arc, preparing to attack each of the first three, but chance combat alerted each town to the contra presence. Finally, Mike Lima feinted with a few contra platoons as though preparing to attack Yali anyway. Then he forced his men to march at double time through the night to the east, regrouping his entire task force at a hacienda he’d chosen as a staging area just 10 miles west of Pantasma. On the eve of the attack, Mike Lima called together his 25 top officers to discuss his objectives in the town and the importance of the attack. He didn’t have to introduce his men to the geography of the town; most were from nearby villages anyway.

Pantasma, a settlement of timber shacks and stores where cowboys and small coffee farmers rode mule-back to buy supplies, sat on the fertile floor of a broad valley 15 miles north of Jinotega’s provincial capital. Spruce-covered ridges loomed to the south and north. The town’s internal geography was linear; homes, stores, offices, warehouses and garrisons lined the gravel road for nearly four miles through the valley.

Mike Lima handed out targets. Most hugged the road. One contra detachment would throw up an ambush along the town’s southern approach – the side nearest the army brigade in Jinotega–to hit any arriving government reinforcements. Another company would attack militia posts guarding the bank and other government offices clustered at the town’s southern entrance. About a mile further into town, another detachment would strike at the 15-man Sandinista police outpost. A half-mile further, Mike Lima would set up his command post at the school in the main settlement. About two miles to the north, another company would assault the town’s principal defense, a roadside garrison serving as headquarters to an army battalion. Munitions stockpiled at the battalion could supply the Diriangen for months, Mike Lima told his men. Another unit would hit the Ministry of Construction yard on the town’s far northern edge, where a dozen dump trucks and other construction machines were parked. The government was punching a new gravel road north to the Honduran border, hailing it as a major contribution to economic development. But the road had a military purpose, enabling government convoys to move, fast, all the way to the border for anti-rebel operations. Finally, two companies of contras would move on two cooperatives near Pantasma, home to some 125 militias.

Pacing before his men under a harvest moon, Mike Lima outlined the stakes. He knew everybody was exhausted. But he wanted this attack to leave an impression on the Sandinistas, to say something about what kind of men were fighting in the FDN. The risks were high, very high, he said. If the Diriangen attacked, but failed to overrun an exposed town like Pantasma, it could get pounded by a terrible Sandinista counterattack. Retreat would be bloody. And after a month of combat, we’re down to about 100 rounds of ammunition each, he said.

“I’m tired of fighting for hilltops. Let’s seize a real prize,” Mike Lima said. “We have to sacrifice. Take this town at all costs!”

He ordered his men into a second night of double-time march east across the mud of the valley floor toward Pantasma. To ensure that the Diriangen’s lightning move would raise no alarm, Mike Lima and a squad of his best men led the way–wearing captured Sandinista army uniforms–detaining every peasant that chanced across their path. The contra units slipped into positions in and around the town under cover of darkness. Mike Lima himself, along with a staff detachment of 60, penetrated right to the center of Pantasma, throwing up a radio command post in the town school to communicate with his company commanders. Then, just before dawn, October 18, Mike Lima’s men opened fire.

Much of the town fell within an hour. Surprisingly, the armed activists at the Sandinista Front’s Zonal headquarters put up the least resistance. Taken completely by surprise, they fled the town. The State-run Agrarian Development Bank offices were also a pushover. The eight militias on guard gave up without a shot. The contras forced them to lie face down on the bank’s tile floor, while somebody went to get the keys to the safe, pulling the bank manager from his bed. Within minutes, the contras were carrying off bags stuffed with 830,000 cordobas–then worth about $30,000. The rebels sent the prisoners from the bank to Mike Lima’s command post, then set the bank afire. Across the road at Encafe, the government coffee agency, and at the warehouse of the Agrarian Reform Ministry, the rebels encountered only minimal gunfire. Inside, they put the torch to more than a dozen tractors and jeeps. East only the road, at the government medical clinic, a doctor and three nurses emerged pleading for their lives. Mike Lima’s men ordered them to load all their medicines onto mules. By now, oily smoke was curling skyward from several points in the town.

Other offices weren’t so easily taken. The Sandinista Police fought fiercely from inside their sandbagged command post, and after a half-hour of combat made a strategic retreat, crossing the road through a culvert and taking up positions in a private sawmill. From there, they drew the first contra blood with sniper fire. Several dozen militiamen at a collective a half-mile away took up good defensive positions; only slowly, over several hours, were the contras able to overwhelm them. The attack on the army battalion headquarters came late, and from the start was tough going because of fire from a government machine gun nest. The most surprising early resistance came from ten Education Ministry employees who holed up inside their offices, a warehouse made of rough wooden planks, piled with bags of food. Seven were teachers, three were women. Armed only with Czech automatic rifles but with plenty of revolutionary zeal, they refused to yield to the contra calls for surrender.

“Eat shit, Guardia swine!” the teachers yelled from inside the building. “We’re not chocolate-assed militias–we’re Sandinistas!” They were totally outnumbered–some 35 contras had taken up positions around the offices with automatic rifles, a machine gun and grenade launchers. The teachers’ insults threw the contra company leader into a rage.

“Blast the bastards,” he shouted to his men. Moments later, a grenade slammed into the building, showering the teachers in burning phosphorus and setting the walls ablaze. Hundreds of Pantasma residents listened in horror to the teachers’ screams as the building collapsed in flames around them.

The wailing and explosions aroused emotions on all sides. One of Mike Lima’s squad leaders took fire from the Enabas offices, the government basic grains office. Enraged, the contra charged the office, killing two defenders, and seizing two prisoners, one of them wounded. These he dragged straight out into the road where dozens of residents could watch. He executed them both on the spot with a burst of automatic rifle fire.

Mike Lima, a mile to the northeast at his command post in the Pantasma school, ordered a shack-by-shack search through the town’s main settlement for arms, Sandinista documents, or government officials. Contra fighters ordered residents to the plaza in front of the school, separating those wearing combat boots or who for some other reason looked like Sandinistas. By 7 a.m., more than 500 terrified residents jammed the plaza, standing in silent rows facing the school. Mike Lima’s men were guarding 20 Sandinista suspects at one side.

Mike Lima was, intermittently, shouting through a squawking field radio to his company commanders, then stalking back-and-forth in front of the building crowd. His men, attacking the battalion and the police garrisons, were facing tough resistance. He didn’t know how strong the Sandinista defenders really were at either stronghold. He wanted his prisoners to tell him–right away. He decided on a public interrogation. It would produce intelligence, Mike Lima figured, and it would serve as a political demonstration to Pantasma’s people: The contras were not joking. They were ready to do anything necessary to prevail.

He ordered aides to pull out two men they believed were Sandinista military leaders, one an army lieutenant, the other a zonal officer for State Security.

“If you don’t cooperate, you’re going to die!” Mike Lima shouted at the two men. “Now, how many Sandinistas are at the battalion?” The prisoners stood mute. Mike Lima signaled to one of his soldiers, who dragged the lieutenant out and stood him up against a wall, a few yards away. Then he blasted him in the face with several shots from an AK47 rifle. Mike Lima turned back to the other prisoner.

“How many Sandinistas are at the police?” Mike Lima screamed at the State Security officer. Silence. A contra dragged him over and shot him, too, next to his comrade -in-arms.

At that, first one, then several other prisoners agreed to cooperate. They detailed what they knew of Sandinista troop strength at the two remaining strongholds. There were only a handful of police in the sawmill, fighting off dozens of contras, they said. Armed with that information, Mike Lima ordered a new assault. His commandos rushed the mill with knives drawn, stabbing the final handful of Sandinista holdouts to death. The wooden structure, already blazing, burned to the ground.

Most of Pantasma was in the hands of contras exhausted, ravenous and now, lost in the delirium of certain victory. They grabbed and slaughtered a pig; soon it was roasting over an open fire. Some townspeople began to bring out tortillas, beans–and beer. Many contras were soon feeling the drink. Some fanned out for mischief, stealing combat boots off residents’ feet, dragging teenage girls into the weeds. For a while, Mike Lima lost control of his men, but he thought they deserved a break. He was throwing back beers himself, buying boots, clothing and food from local merchants with the booty from the bank. He spent 430,000 cordobas that afternoon–the equivalent of about $14,000.

Meanwhile, two miles north, the battle still raged at the battalion. By early afternoon, however, Mike Lima’s men knocked out the machine gun, allowing them to storm close enough to fire a rocket-propelled grenade. The projectile crashed into the battalion’s main munitions stockpile, setting off an extraordinary blast that hurled men and metal hundreds of feet and sent a mushroom cloud of inky soot billowing skyward. Those Sandinista soldiers who survived, fled. It was a lucky shot; it ended the army’s resistance. On the other hand, it had utterly destroyed the arms stockpile that had been Mike Lima’s major objective. The only prize remaining was the construction yard. Unfortunately, militias there, too, forced the attackers to fight for every truck. But eventually the yard fell, and the Diriangen’s demolitions men went to work. They burned 10 government dump trucks and crippled six heavy road graders.

Finally, Mike Lima rallied his drunken troops and ordered a retreat to a nearby hacienda.

He left behind the bodies of nearly 50 dead soldiers, police, militiamen and residents–including the charred remains of seven teachers–strewn amid the ruins of every government installation in town. The government estimated the damage at $2 million to the road equipment alone. Pantasma was a town in ashes.

Mike Lima had utterly vanquished his Sandinista foe. But, ironically, he was still short of munitions, boots and other supplies. He marched his men north, radioing for another CIA air drop. A Sandinista battalion caught up with him just days later, forcing him to retreat, on the run for two weeks, all the way north to the Honduran border.

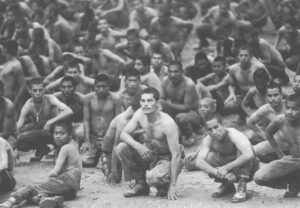

He and his men staggered in, exhausted and starving, to the FDN recruiting base at Banco Grande in mid-November. Back in the FDN rearguard, Mike Lima got a hero’s welcome. The CIA dispatched a helicopter out to Banco Grande to fly Mike Lima to Tegucigalpa. A CIA agent known as Alex clapped him on the back, and carried him to a laudatory tête-à-tête with the Agency’s CIA base chief in a Tegucigalpa safehouse.

“I was the CIA’s golden boy,” Mike Lima recalled later.

©1990 Samuel Dillon

Samuel Dillon, a reporter for the Miami Herald, is exploring the roots of Nicaragua’s contra war.