When several angry Nicaraguan contra field commanders last year challenged Enrique Bermudez, the rebel army’s “Supreme Commander,” their first tactical move reflected the dynamics of power within the anti-Sandinista movement: they called the U.S. Embassy in Tegucigalpa to request a meeting with the CIA station chief.

Several days later, Diogenes “Fernando” Hernandez, one of the dissident rebel officers, got a phone call at his rented home in the Tegucigalpa capital. It was a CIA official known as “Terry,” a dark-haired American of about 40 with a good command of Spanish whom Fernando had met a few times when the agent had helicoptered into the rebels’ border base camps. The American at first insisted on a one-on-one meeting with Fernando. But later he agreed to a group encounter.

The meeting came days later, one afternoon in April 1988, at the home of a U.S. Embassy political officer. With Fernando were two other rebel commanders leading the challenge to Bermudez, Walter ‘Tono” Calderon, 32, and Tirzo “Rigoberto” Moreno, 33. Terry and several other U.S. officials sat around in stuffed chairs listening to the dissident commanders’ complaints about Bermudez, scribbling notes onto legal pads.

Fernando, 29, a Protestant preacher-turned-rebel battalion commander, broke the ice with a summary of the complaints against Bermudez, accusing the former colonel in dictator Anastasio Somoza’s National Guard of military incompetence, financial corruption and political ineptitude. Tono and Rigoberto joined in, complaining that Bermudez had never once entered Nicaragua to fight during the contras’ entire eight-year war and that he had installed unsavory Guard cronies in the rebel army’s most important and lucrative posts. They listed several of Bermudez’s aides by name, accusing them as thieves, thugs and murderers.

The dissidents went on for a little over an hour. Then Fernando laid out the bottom line: they wanted Bermudez to leave Honduras and move to Miami, to join the contras’ political directorate. In his place, a junta of rebel commanders would run the army.

There was a pause. Terry glanced around at the other Americans, then leaned forward in his chair.

“We’ll be frank—we’re not going to support you. The position of the U.S. government is to support Enrique Bermudez,” he said.

The CIA agent stuck by his word. It was not the first commanders’ challenge to Bermudez the CIA had been forced to confront since recruiting Somoza’s one-time military attaché in Washington to lead the U.S.-financed rebel effort in 1981. This time, as on earlier occasions, the CIA weighed in heavily with thinly-disguised bribes and intimidation to bolster Bermudez’s shaky control, finally arranging the detention and deportation to Miami of the dissident officers.

Nonetheless, the rebellion tore at the cohesion of the insurgent movement for several crucial months when the rebels were negotiating over a cease-fire with the ruling Sandinistas. When it was over, Bermudez was in tighter control than ever—of a demoralized army facing a bleak future. Bermudez had broken off the talks, the only promising option left to the rebels after the latest U.S. aid cutoff. Several of the rebel army’s most influential commanders were gone for good. And tens of thousands of contra sympathizers inside Nicaragua, sensing rebel demise, were heading north to Texas in a mass exodus to seek political asylum.

It was a crippling upheaval, sudden and unforeseen. It came two months after the U.S. Congress’s latest military aid cutoff and three weeks after the signing of the controversial Sapoa cease-fire agreement. It underlined the myriad of mini-conflicts inside the rebel organization: former National Guardsmen distrusted former Sandinistas; front-line combatants resented rearguard logistical officers; unpaid soldiers envied the officers with their CIA-paid salaries and pickup trucks. The men in Honduras saw the rebels’ Miami office as a swamp of overpaid bureaucrats. The tensions had all been aggravated when the traumatic cutoff of U.S. military aid in February sent many rebel commanders trekking back into Honduras, angry and harassed, dragging their wounded. When they found Bermudez largely unavailable in Miami or holed up in his Tegucigalpa safehouse—he became a lightning rod for the criticisms of a frustrated movement.

Bermudez’s most powerful enemy was Adolfo Calero. The two had been rivals since 1983, when the CIA recruited Calero to leave his job as a Managua Coca-Cola executive to head the contra political directorate. Bermudez, who considered himself the contra army’s founder, resented his sudden subordination to Calero. The antagonisms deepened during the 1987 Iran-contra revelations, when Bermudez was surprised to learn how Calero had personally controlled some $32 million in Saudi and other funds channeled to the rebel movement by Oliver North during two years when official U.S. aid to the contras was illegal. The antagonisms flared into public in the weeks after Calero and two other rebel political leaders signed the Sapoa accord in March 1988. Bermudez denounced the accord as a sellout-even though several of his own close aides helped negotiate it—directing his blame at Calero.

Calero’s brother-in-law, Enrique Sanchez, and several other close aides were at the time working for the contra organization in Honduras. They included the rebel army’s paymaster. Orlando Montealegre, and its top lawyer, Donald Lacayo. As Calero nursed his anger at Bermudez, he began financing an anti-Bermudez campaign in Tegucigalpa, and his aides began meeting for anti-Bermudez bitterness sessions with Fernando, Tono and Rigoberto.

Fernando and Tono had both been members, with Calero. of the rebel negotiating team, and Bermudez had criticized them for their role in the negotiations, however limited. But other, older grievances played a larger part in their decision to challenge Bermudez.

Fernando was a soft-spoken leader with long eyelashes, evangelical Protestant sensibilities, and a long combat record as a battalion commander inside Nicaragua. But during much of 1987, he worked with Bermudez at general staff headquarters at Aguacate Air Base, the sprawling, CIA-constructed hub for night supply flights. At Aguacate, Fernando said he discovered the underbelly of the contra movement: thieving by Bermudez’s logistical officers, brutality by Bermudez’s military policemen, blind submission by Bermudez himself to CIA dictates. Fernando recalled a comment by Bermudez that stunned him during a 1987 meeting: “The CIA has never permitted me to make decisions. Always, what they say goes,” Bermudez had said.

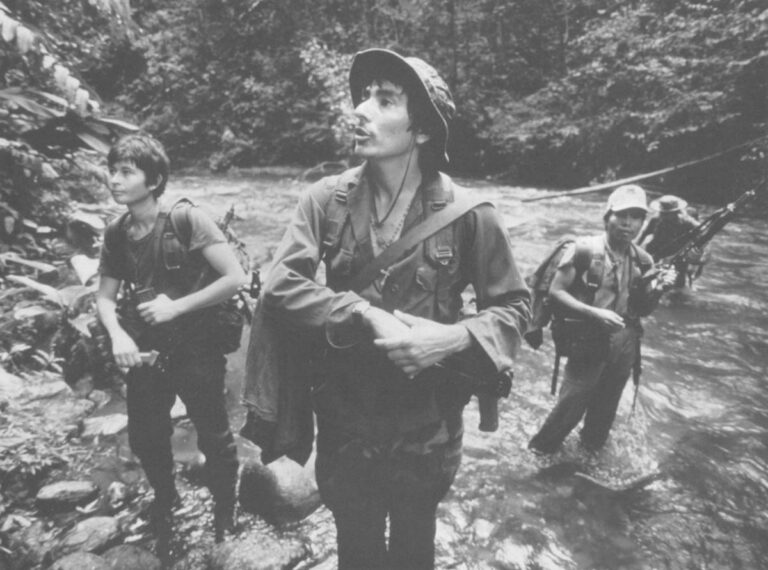

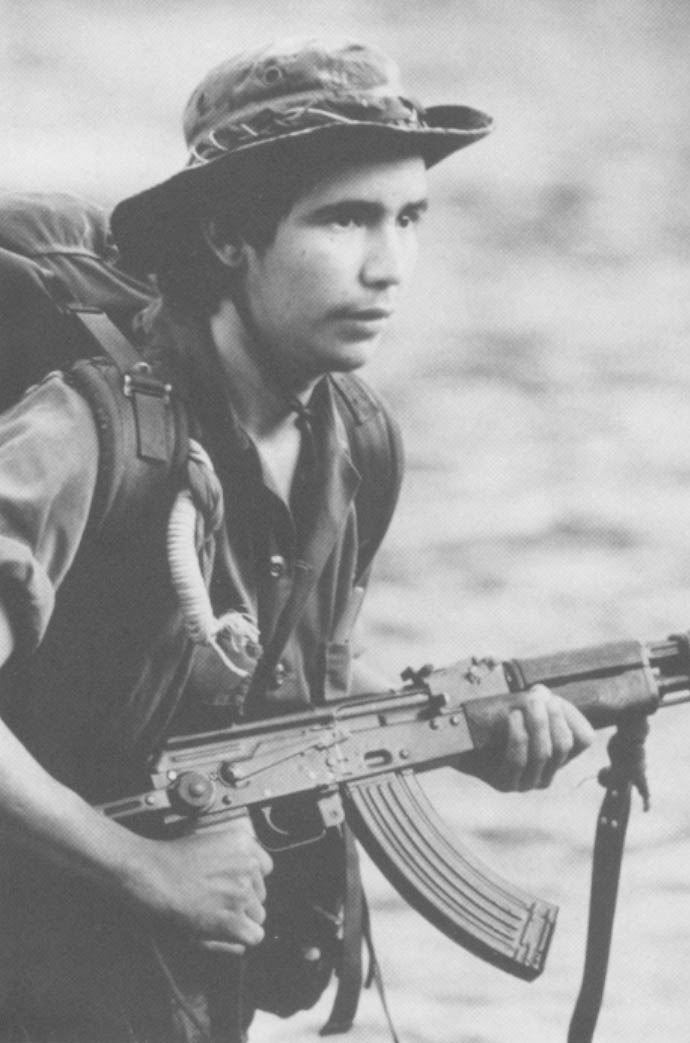

Rigoberto, a muscular onetime cattle merchant, turned against Bermudez watching the ex-colonel repeatedly brush aside rebel commanders returning from long incursions into Nicaragua, uninterested in their wartime experiences. Instead of probing for intelligence data, Bermudez left the debriefing of returning commanders to CIA agents. For Rigoberto, a dedicated commander who had led a 1987 attack on a mining****

The seeds of dissent for Tono, a dark-haired rebel officer with chiseled features, were planted in the fall of 1987, after he joined the rebel negotiating commission. Tono was thrust into a jet-setting lifestyle of hotels and restaurants, airports and interviews. He said later that his experiences opened his eyes for the first time to the way Bermudez’s background as an ex-Guard colonel tarred the rebel movement with an outdated, Neanderthal image.

As an ex-Guardsman himself, however, Tono was not well-positioned to hurl stones, and his detractors explained his sudden insubordination as an expression of the sudden vanity that gripped him, moving as a rebel negotiator through the international spotlight. Overnight, Tono seemed to prefer jacket-and-tie to combat fatigues. He began lifting weights in a Tegucigalpa health club.

And when the rebels’ 30-man Commanders’ Council met in February to elect a new general staff, Tono was stung when his colleagues elected a former subordinate instead of himself as chief of staff. Rigoberto and Fernando were also disappointed by the staff elections. Rigoberto was made civic affairs chief, the post charged with attending to rebel refugee families. It offended his commander’s pride. “I’m going to be delivering milk?” he asked. Fernando was forgotten entirely in the voting.

Joining these dissident commanders was a fourth, Encarnacion “Tigrillo” Baldivia, 31. He had been a bandit-guerrilla in northern Nicaragua before there was U.S. aid and had brought hundreds, perhaps thousands of recruits into the rebel army. Tigrillo’s anger at Bermudez traced partly to his belief he was being cheated in the allocation of war supplies. Fighting inside Nicaragua, Tigrillo recalled, he would radio for an air drop, then watch for weeks as CIA planes passed overhead on their way to dump supplies to Bermudez’s favorite ex-Guardsmen.

Before challenging Bermudez’s authority openly, the dissidents sought his cooperation in a face-saving “restructuring” plan under which the supreme commander would, with army backing. move out of Honduras to Miami to join the rebel political directorate. They first floated the idea in early April in a Tegucigalpa meeting with three top contra officers close to Bermudez. Whether the three aides ever voiced support or not—the dissidents claim they did—their first move was to report the encounter to Bermudez, who immediately launched his own counter-offensive. Bermudez boosted his three top aides’ U.S.-paid salaries in return for their continued loyalty, and offered, through representatives, to cut a financial deal with the dissidents, too. The dissidents refused. The rebellion was on.

But instead of proclaiming their rebellion Latin-style, from the base camps, entrenched behind their troops, the dissidents adopted a remarkably un-military strategy, based on petitions and persuasion. This probably reflected the influence of Calero’s aides, all civilians. who were meeting with the dissidents and drafting many of the documents.

With Calero and associates paying the bills, the plotters rented a suite at Tegucigalpa’s Alameda Hotel to set up an informal headquarters and on April 16, hammered out a 5-page manifesto on a borrowed typewriter. The document compared Bermudez to Somoza, blaming him for “autocratic” leadership and abuses against rebel fighters in Honduran base camps. It concluded with a call for Bermudez’s replacement by a commanders’ junta.

Then the dissidents fanned out to all the rebel enclaves in Honduras, seeking signatures for the manifesto. The campaign climaxed on a weekend in April at the Hotel Granada in Danli, a Honduran border town heavily populated with contra families, where the. dissidents rented several rooms; and lobbied wavering commanders with liquor and cash payments. Twelve of the army’s 32 regional commanders and a few dozen other influential fighters eventually signed the anti-Bermudez petition.

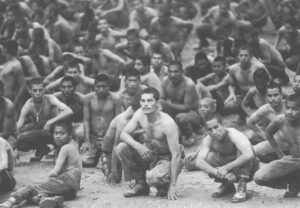

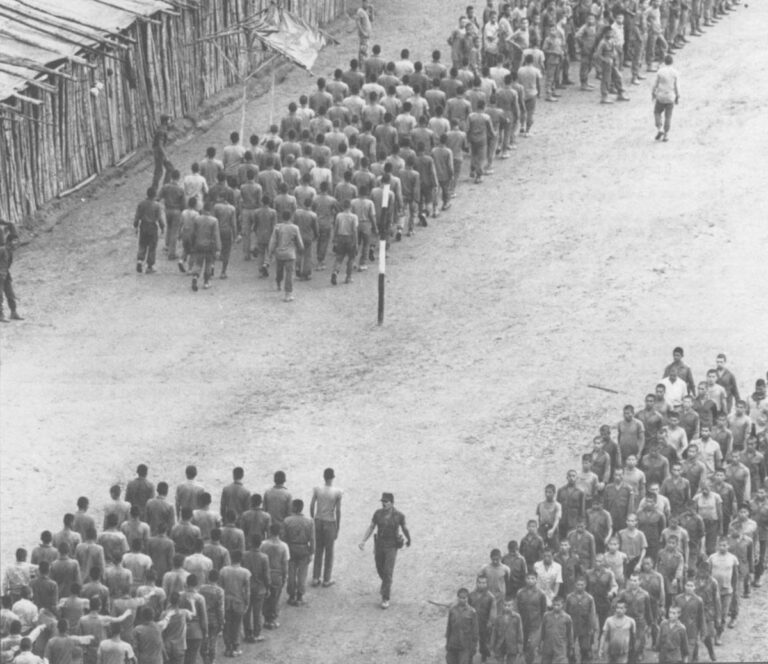

But Bermudez and the CIA were organizing a counterattack. Bermudez seized the dissident’s CIA-paid vehicles, cut off their U.S.-paid salaries, and expelled Fernando and Tono from the rebel negotiating team. The same weekend the dissidents were in Danli, U.S. officials arranged a pro-Bermudez rally at Honduras’ Sixth Army Battalion, a pine-shaded base to which several hundred rebel fighters and their families were trucked for an afternoon of speeches and free food. With several CIA agents watching on, Bermudez warned that the dissidents had been “turned” by the Sandinistas in the peace talks, holding up to the crowd poster-sized blowups of a photo taken at Sapoa showing Tono chatting with several Sandinista officials. In another massed meeting of 100 rebel officers in Tegucigalpa the following week—also attended by several CIA agents—Bermudez formally relieved the dissidents of all rank.

Circulating their own petition denouncing the dissidents for “favoring Sandinismo.” Bermudez’s people were also distributing cash to signers. Several officers later reported that the size of their monthly officers’ salaries had come up for discussion before they signed for Bermudez. Eventually, 19 regional commanders inked the Bermudez petition. Two regional commanders took advantage of the sudden cash flow to sign both petitions.

By the last week of April, Tono sensed the way the winds were blowing. He called together several journalist friends. and, for the first time publicly, on-the-record, denounced Bermudez.

“He’s a dictator just like Noriega or Castro,” Tono told the reporters. The dissidents were going for broke. They moved from the Hotel Alameda to the much more expensive Maya, preferred by journalists. Two days after Tono’s first sensational interview, he was joined by the rest of the dissidents for a virtual press conference with correspondents for Newsweek, the Washington Post and other reporters.

The public declarations violated the rules imposed by Honduran authorities on all contra leaders—no Honduras-datelined interviews. The following morning, May 4, Honduran security agents detained all the principal dissidents except Fernando and Tigrillo in their Maya Hotel suite. Hours later, they picked up Tigrillo in Danli. (The same day, Bermudez. Calero and other contras were meeting in Washington with Secretary of State George Shultz.)

Two days later, the seven dissidents were deported to Miami. Fernando escaped. Warned by a young rebel just as he was arriving at the Maya Hotel May 4, he drove east to the border camps, skirting several Honduran military checkpoints, and visited the units once commanded by him and the other dissidents. He was received with abrazos. He radioed staff headquarters with a message: dissident units would no longer obey Bermudez’s orders and Bermudez loyalists were barred from dissident camps. He said he wanted members of the rebel political directorate to travel to Honduras to hear the case against Bermudez.

The standoff lasted three days, and brought the only bloodshed of the rebellion. Troops loyal to Bermudez fired on several dissident troops bumbing along a road from one camp to another in Fernando’s jeep, wounding two.

In Miami, the dissidents’ deportation had aroused considerable sympathy among staff employees at the contra offices on the north edge of Miami International Airport, and with two other members of the five-person directorate, Azucena Ferrey and Pedro Joaquin Chamorro, the son of Nicaragua’s martyred newspaperman. Ferrey and Chamorro fled to Honduras to mediate. They encountered a predictably hostile reaction from CIA and other U.S. officials when they outlined suggestions for conciliation. Chamorro told one CIA agent that he believed the civilian directorate enjoyed the institutional power to replace Bermudez if it so decided.

“I admire your idealism, but let’s be realistic,” the agent jeered back.

CIA and Honduran authorities used the directors as bait to entice Fernando away from his troops and definitively end the rebellion. Three Honduran military officers drove to the base camps and told Fernando that the contra directors were waiting for him at the 6th Battalion base. Fernando climbed into their jeep—and soon realized he was under loose detention.

The next morning at the 6th Battalion, Fernando was led into a meeting with Ferrey, Chamorro, two Honduran colonels, and two sympathetic rebel officers who had driven to the base on their own to participate in the meeting. The Honduran officers reacted icily to all suggestions for compromise. One of the other rebel officers pulled out his own reform plan. The atmosphere was sufficiently tense that Ferrey looked with alarm at the document: “Hide that or they’ll deport you too!” she whispered.

After the meeting, Fernando was taken to Tegucigalpa, held for three days, and deported to Miami. He was never even allowed to change his clothes.

The deportations effectively ended the rebellion, but the CIA’s heavy-handed tactics brought further embarrassment to Bermudez and the CIA in Miami. The intimidation particularly angered Chamorro, whose feelings deepened when a CIA agent called him to complain about visits by the dissidents to the contra’s offices.

“They kicked you out of Honduras, now they want to kick you out of our offices,” Chamorro told the dissidents.

Chamorro drafted a proposal to remove Bermudez and presented it to the directorate May 14. Bermudez’s main political ally, Aristides Sanchez, left the room, phoned a veteran CIA agent known to the contras for several years as “Jorge.” A speaker phone was set up in the meeting room. Chamorro’s proposal was read aloud to the agent over the phone.

The CIA agent lashed into an angry diatribe against the directors, especially Chamorro. He called Chamorro “stupid…an imbecile,” and said that the contras deserved no more U.S. aid. The directors sat speechless while the agent blasted away for more than 20 minutes. Chamorro slumped into a couch, trying to keep his cool.

“We don’t respond to insults,” Calero said when the Agent finally paused. The meeting broke up.

The dissident rebel officers had arrived in Miami virtually penniless. Tigrillo’s situation was hopeless: illiterate, his knee stiff from a war wound, he limped Miami’s mean streets for a time, then got work picking lemons as an illegal on a south Florida migrant farm. Months later he returned illegally to Honduras and at last report was in Honduran detention. Tono found work as a surveyor; Fernando took a factory job. Rigoberto applied for political asylum, but a year later found that his application—routinely approved for Bermudez loyalists—was stalled. He still couldn’t work. Months after the dissidence, the three dissidents got the number of the Miami CIA station and a young, blonde agent came out to their bleak apartment block to talk. He listened to their complaints about Rigoberto’s asylum petition and requests for economic help getting started, then said he’d be calling back. He never did.

©1989 Samuel Dillon

Samuel Dillon, on leave from the Miami Herald, is exploring the roots of Nicaragua’s contra war.