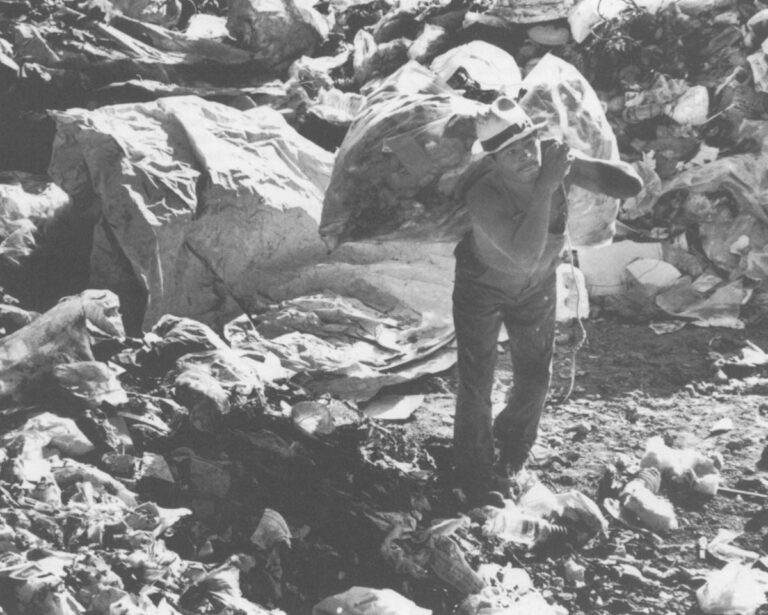

MEXICO CITY–Augustina Cruz lives in the western fringe of Mexico City in a one-room ramshackle house built of broken boards and cartons and a rusty strip of metal for a roof.

Each morning Cruz, 45, a widowed mother of five, walks the short distance to the Santa Fe garbage dump where she and hundreds of others pick through the city’s residue, scrounging for glass, paper, cardboard and a myriad of assorted metal and wire to sell for fractions of a penny per pound. On a good day she makes about $4.

Below the dusty hillside where Cruz lives, the Iberoamericano University sprawls. The low red brick buildings comprise one of the most elite institutions of higher education in Mexico. Nearby, another bastion of prosperity; the walled-in complex where former President Jose Lopez Portillo and his family live. The estate is popularly known as “dog hill” a reference to the former president’s ill-timed vow to defend the peso “like a dog” shortly before it was devalued.

The acute contrast illustrates one of Mexico’s most disturbing social dilemmas, and one of the biggest impediments in recent decades to development; a skewed distribution of income that analysts say is one of the worst in the hemisphere. Since Mexico entered a severe economic crisis in 1982, social disparity has become more pronounced because of the burden of the $106 billion foreign debt. In the last six years Mexico has made a net transfer of $48.7 billion in foreign debt payments.

“Before, unequal income distribution was compensated by a system of social benefits ranging from transportation subsidies to public health,” said an economist affiliated with the Autonomous Metropolitan University, in Mexico City. “An equilibrium was maintained. But with the debt this has disappeared.”

After six years of economic stagnation Mexico is poised to integrate into the world economy, a route viewed as the only way to pull the country out of depression and grow once again.

But as Mexico embarks on the difficult challenge of modernizing its economy, it is faced with deteriorating social conditions that many analysts say could jeopardize the program’s eventual success.

“The cost of modernization is that some will be entering the 21st century while others are left behind in the 19th century. Those that are living in the past have augmented in the last six years. This has occurred at a time when the economy is modernizing,” said Ugo Pipitone, an economist with the Center for Economic Research and Teaching in Mexico City.

The economic model Mexico expects to in some ways emulate is that of Taiwan and South Korea. Both Asian countries, however, evolved into export giants under different social conditions, analysts say. Both countries had implemented extensive agrarian reform programs as well as curtailed population growth, which resulted in a more even distribution of wealth.

Mexico initiated an agrarian reform program 50 years ago that for the most part failed, largely because of the government’s decision to abandon rural development in favor of urban industrialization. A population boom also overwhelmed whatever small gains were achieved.

“Those countries that have developed export economies don’t have as poor social conditions as Mexico,” said Lorenzo Meyer, an historian with El Colegio de Mexico, a graduate school and think-tank in Mexico City.

“Mexico is a fragmented country with high levels of illiteracy, malnutrition, with an abysmal difference in the level of life. Modernization begins and it aggravates these elements: it is collective suicide,” Pipitone said, adding that in Mexico the top 10 percent of wage earners earn some 36 times what the lowest 10 percent earn. In the United States the richest 10 percent earn only 10 times more than the poorest 10 percent, said Pipitone. In addition, the wealthiest 20 percent of the population in Mexico controls 65.5 percent of the capital while the bottom 20 percent share 2.4 percent, according to a study on income distribution by political analyst Miguel Basanez.

To compete in the international economy officials say Mexico will keep its low wages even lower.

“There is going to be an excess of supply and demand in the labor sector for many years that will put pressure for lower salaries for the Mexican economy to remain competitive,” said Carlos Bazdresch, an economist with the Banco de Mexico, the central bank.

In addition, spending for most social services has also been radically cut, reversing many social gains of recent decades. According to the Inter-American Development Bank, Mexico ranks last among Latin American countries in spending for health and is in 17th place out of 25 countries in spending on education.

According to a study by the Banco National de Mexico, 47 percent of the population was considered poor in 1981, earning twice the minimum wage which is currently about $3.50 a day. At the end of 1987, 60 percent of all Mexicans were classified as poor.

Pipitone and other economists estimate that at least 30 percent of the economically active population is under or unemployed.

“One of every two youths that looked for work between 1982 and 1988 did not find it,” an article in the newspaper El Financiero stated recently, “resulting in a generation without expectations and strong social resentment.”

“There is an economic cost to all of these policies,” said Jorge Castenda, a political analyst. “Between 1982 and 1988, spending for education fell from over five percent of GDP to below three percent in a country where 50 percent of the population is under the age of 15. What that does to your competitiveness is devastating. From a purely economic point of view if you are trying to make Mexico a world class competitor you can’t do it by dividing spending on education by half. Who is going to produce the stuff that will be sent abroad, a bunch of illiterates? It’s a very contradictory policy.”

Some analysts fear that a continued deteriorating of life in Mexico could provoke social frustrations similar to that which led to riots in Venezuela earlier this year.

“In any country where this is happening the potential for social strife is greater,” said Meyer. “There is a deterioration of expectations.”

At the same time, Mexico’s economic transformation is contingent, some analysts say, on domestic growth that would fuel an internal market.

“It is difficult for firms to have a market made exclusively of exports. You have to have some domestic base,” said Casteneda.

“How can you have an economy that doesn’t consume?” asked Meyer.

Theoretically, promoting an export economy would compensate for internal depression, some analysts argue.

“It is quite true Mexico has severe problems in income distribution but that simply means getting on with export success is even more important to help alleviate the distribution of income,” said William Glabe, of the Wilson International Center Scholars in Washington.

But few see any way Mexico can grow while it is paying an estimated five percent of its GDP in foreign debt payments.

“The current situation regarding the foreign debt is blocking economic recovery,” President Carlos Salinas de Gortari said in his inaugural address last Dec. 1, before an audience that included several world leaders. “We will not resume steady growth if we continue transferring five percent of our gross national product abroad each year as we have been doing to date.”

It is uncertain what effect a recent, new debt agreement between Mexico and its major bank creditors will have on the economy.

Salinas hopes the agreement, which should cut interest rates on debt payments, will give a much needed psychological boost to restore the confidence of foreign and domestic investors. Salinas also has said that lower debt payments could free resources to fuel growth.

The success of Mexico’s modernization program also depends on enormous investment from both inside the country and from abroad. The government also recently liberalized Mexico’s investment laws in the hopes of attracting more foreign investment.

The bankrupt Mexican government has sold off a number of state-owned companies and is, in general, assuming the private sector will be the principal promoter of industrial growth in the coming years.

“The success of the modernization program depends, among other things on the private sector resuming investment,” said Bazdresch. “The question is, ‘will the private sector invest in Mexico, yes or no?’ I think it will.”

“The private sector is fit to promote growth, it has an excellent financial position and I think it has awakened to the new challenges,” said economist Rogelio Ramirez de la O.

Some private sector analysts, however say entrepreneurs will remain cautious until there are signs that internal economic conditions improve, a condition many analysts say is inexorably tied to a reduction in Mexico’s debt payments.

“The risks and benefits are not clear,” said Fernando Gomez, of the Mexican Confederation of Chambers of Commerce, commenting on the potential for investment. “If I had an industrial project I would not give it the green light until the question of the foreign debt was resolved. The country is in recession. Until internal demand improves it will be difficult for the private sector to invest. The two key pieces are resolving the debt and reactivating the economy.”

The 1982 crisis was sparked by world recession and a huge drop in the price of oil, Mexico’s principal export, which came on the heels of a huge borrowing campaign that began two administrations earlier. Mexico initiated the world debt crisis when it could not make payments of then $80 billion in foreign debt.

In 1982, Mexico became a net exporter of capital. In the following seven years, the foreign debt has grown to $106 billion and the economy has stagnated. And while these events were the immediate causes of Mexico’s current crisis, the origins go back much further.

It became apparent in the late 1960s that despite significant development and social mobility of preceding decades and the emergence of a middle class, huge social disparities still existed.

In 1968, Mexico confronted a political crisis that culminated in the massacre of an estimated 300 people during a peaceful demonstration in Tlatelolco, the Plaza of the Three Cultures in Mexico City on Oct. 2. In the preceding months, thousands had taken to the streets to challenge the authoritarian government of President Gustavo Diaz Ordaz. And while the 1968 crisis was a manifestation of political discontent, many analysts argue that the underlying motives were economic.

The policies of subsequent governments were directed at defusing the political discontent manifested in 1968 and pre-underlying problems that Alejo said motivated Echeverria’s acserving, at all costs, Mexico’s one party system of government.

But instead of addressing the underlying problems, a series of policies were instituted that paved the way for the 1982 crisis.

The 1968 crisis “demonstrated that the country was confronting, on the hand, a loss of economic dynamics,” said Fransisco Javier Alejo, who as a cabinet minister under Echeverria was one of the orchestrators of economic policy during his administration from 1970 until 1976. “The economic dynamic that the country had benefited from for the preceding decades began to show signs that it was obsolete.” He is currently director of Mexico’s national agricultural warehouse system.

Social pressure, Alejo said, “demanded the direct intervention of the government in the economy with the intent of augmenting the capacity for employment.”

Echeverria served as Interior Minister in the Diaz Ordaz government and in that capacity was one of those responsible for Tlatelolco.

Under Echeverria the government’s role in the economy expanded as numerous bankrupt enterprises were brought up in an attempt to save jobs. His leftist posture both in the economy and in foreign policy alienated Mexico’s private sector. A more restrictive law on foreign investment was passed and at the end of his term he expropriated valuable farm land in northern Mexico.

In retrospect analysts concur that Echeverria’s economic policies never resolved Mexico’s underlying social disparity. Instead, he fueled the economy through government spending financed by foreign loans. The deficit and foreign debt burgeoned.

When Echeverria took office in 1970 the foreign debt was $5 billion. When his successor. Jose Lopez Portillo, came to power six years later, it had grown to nearly $20 billion. The conditions were never resolved and are worse today because of the weight of thc foreign debt.

“Echeverria realized that there was a time bomb and he increased public spending using foreign loans,” said economist Clemente Ruiz Duran. “The 1970s were not very fruitful years. A lot was spent but it did not resolve the problem of poverty.”

The economist noted, “The economy under Echeverria stopped being productive because of foreign credits. If there wasn’t enough corn, you could simply buy it with credits without resolving the underlying problem.”

Glabe added, “The orgy of foreign borrowing was by almost any calculation a bad policy, as was public spending which was widely out of control as well as the tolerance of burgeoning corruption.”

In many ways Lopez Portillo followed the same policies as Echeverria, analysts say, but the oil boom fueled Mexico’s capacity to borrow from abroad even more.

“Lopez Portillo saw that borrowing was the easiest way. He repeated what Echeverria started but in the extreme,” said the economist.

The public and private sector borrowed $60 billion during Lopez Portillo’s administration. One-third of that amount was borrowed in 1981 in a desperate attempt to try and keep the country going while revenues were falling and interest rates were rising.

During his last state of the nation address in 1982 Lopez Portillo nationalized the banks.

“Mexico under Echeverria and to some extent under Lopez Portillo was trying to accentuate an economic model that had been obsolete, protected industrialization based on heavy state spending with neglect of agriculture and exports,” said Glabe.

When Miguel de la Madrid took office in 1982, Mexico was a net exporter of capital. The administration faced the challenge of initiating liberalization of Mexico’s protected economic modernization. But De la Madrid’s promises were basically rhetoric until 1985.

“The government liberalized the economy very late in the administration,” said Bazdresch. “It didn’t foresee how far it would have to go to reach the point where these changes would be effective in attracting private investment.”

Still reeling from the bank nationalization, Mexico’s private sector refrained from investing in the economy as well.

“Why didn’t the private sector react in 1983? The solution to the debt problem at that time did not allow for a favorable perspective for growth. Besides, there was the problem of the nationalization of the banks,” said Bazdresch.

Seven years into the economic crisis Mexico still suffers the social disparities that first became apparent two decades ago and is worse off because of the foreign debt.

It is unlikely conditions will improve in the near future with government officials acknowledging that the country will not, even, under the best of conditions, grow significantly for awhile.

“This is a year of transition,” said the government finance official. He added that while the government is concerned about the social and economic deterioration of Mexico, there seems to be no immediate solution.

“The social deterioration could stop, that would be a major step,” said Ramirez, adding, “It is difficult to recover what has been lost.”

©1989 Suzanne Bilello

Suzanne Bilello, a reporter for Newsday, spent last year researching the effect the events of 1968 had on Mexico’s political future.