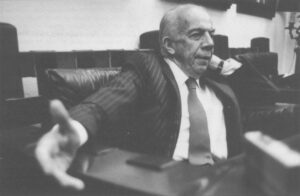

For most of his adult life Samuel I. del Villar, a former Mexican government official and prominent intellectual, was a member in good standing of Mexico’s ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party, PRI, and a staunch defender of the one-party system.

But in the aftermath of the controversial July 6 presidential and subsequent state elections, del Villar, who coordinated an anti-corruption program under former President Miguel de la Madrid, decided to resign from the party he had been a member of for 25 years.

In an acerbic letter of resignation last November, del Villar summed up his opinion of the PRI. “In fact the PRI has converted into the party of imposition and social injustice, totally corrupting its standard of democracy and social justice,” he said.

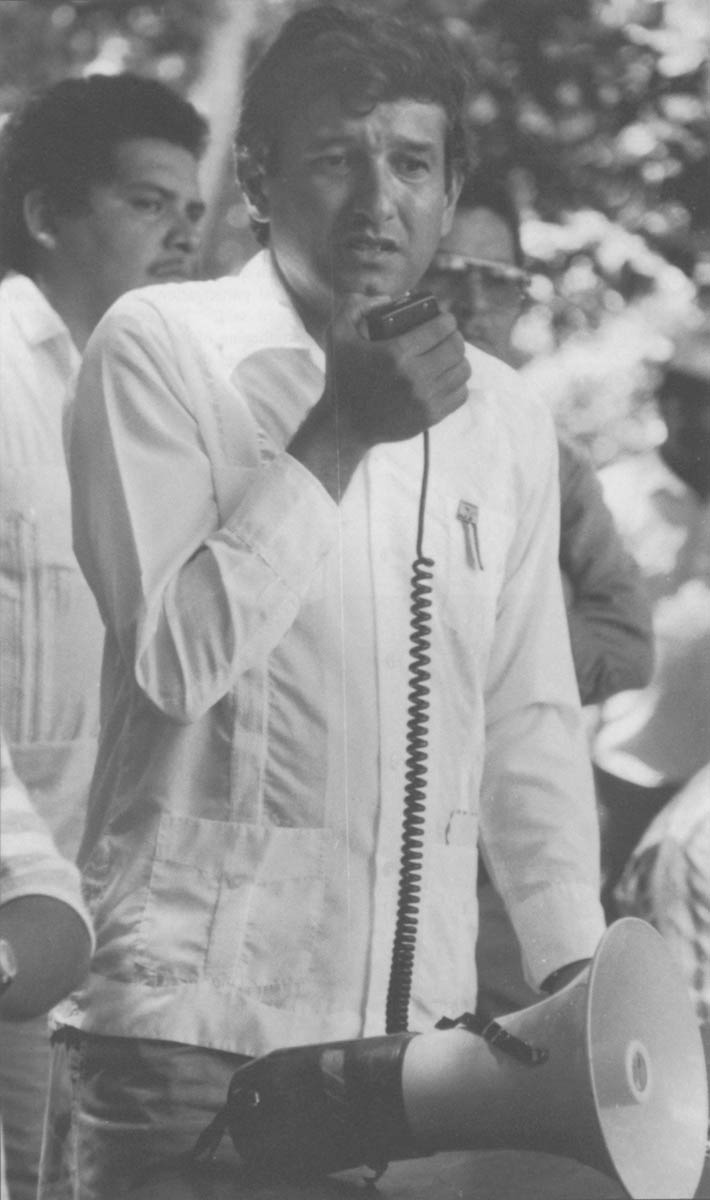

In the oil-rich state of Tabasco, site of controversial state elections last November, Jorge Rodriguez Hernandez, a 34-year-old petroleum worker was also, until recently, a supporter of the PRI.

Rodriguez and several dissident workers at a Pemex, the state oil monopoly installation in Cuidad Pemex, said they broke with tradition and voted for the center-left opposition in the November state elections.

“There is a revolution going on inside the PRI,” said Rodriguez.

In July, presidential election PRI candidate Carlos Salinas de Gortari was elected with an historically low vote amid widespread irregularities that left the true outcome a mystery.

One of Salinas’ most important challenges in the next six years is to salvage the party and consequently, the system that has ruled Mexico for six decades, a task analysts from within and outside the party question how and whether it can be accomplished.

“It’s a party in agony,” Luis Javier Garrido, historian of the Mexican political system, said of the PRI. “They will have to create a new party because they can’t reconstruct the ruins.”

Salinas won the July presidential election with barely a simple majority of the vote. His predecessor Miguel de la Madrid captured 70.9 percent of the votes six years ago. In July, Cuauhtemoc Cardenas, candidate of the center-left National Democratic Front, FDN, who until last year was a member of the PRI, came in second. Manuel J. Clouthier, of the center-right National Action Party, PAN, came in third.

The election results were largely attributed to discontent spawned by six years of harsh economic crisis. At the same time years of neglect, corruption and flagrant abuses of power have also alienated Mexico’s ruling party from the citizenry more than at any time since the party was formed in 1929.

“In voting for the opposition Mexicans rejected not only the economic crisis but understood also that this was a consequence of the political regime,” says Garrido.

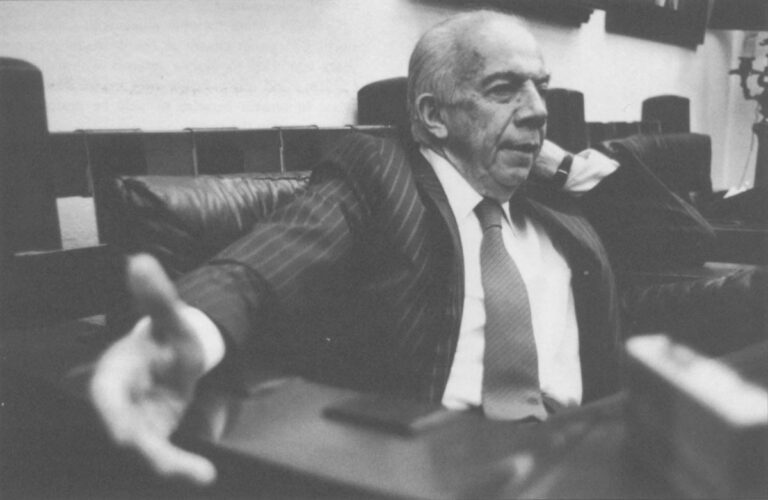

“Those that say there is no crisis in the party are terribly mistaken,” Rodolfo Gonzalez Guevara, a PRI activist who has held numerous posts in the PRI and the Mexican government, said in an interview.

A precursor to the PRI was formed by President Plutarco Elias Calles as a means to stop factionalism following the 1910-1917 revolution. Since then the party has, for the most part, been indistinguishable from the state.

Salinas, an economist educated at Harvard, and aides say they recognize the party’s failures and are committed to carrying out profound internal reforms to revive the PRI.

“For our part we will maintain our democratic posture and our will to reform,” said Manuel Camacho Solis, who until December was secretary general of the PRI. He added the party has to abandon its bureaucratic structure as well as practices of “supremacy, corruption and recuperate political practices that have characterized, in the best of moments, the life of our party.”

For decades the party’s failures have frequently been masked by fraudulent electoral results and an uncanny ability to co-opt opponents that leave many wondering where, if anywhere, the party’s true constituency lies.

“The PRI doesn’t have active members like other modern political parties,” said Roger Bartra, a Mexican sociologist. “There are no active citizens convinced by the party agenda.”

Numerous irregularities during and after the July 6 election cast doubts on the true outcome and tarnished Salinas’ and the new PRI administration’s image.

Officials in the PRI recognize the difficulty Salinas faces because of the scar left by July’s election.

“Salinas is not going to begin his term like other presidents. He comes in weakened because of the electoral question, a lot of people have the impression the process was not clean,” said Maria Emilia Farias, until recently a member of the PRI’s National Executive Committee and one of the more outspoken promoters of party reform. “The first year will be very difficult.”

Moreover, continued pressure by the opposition and divisions within the ruling party over proposed reforms further complicate Salinas’ administration.

Concern within the party over the difficulty the Salinas administration faces was emphasized in an internal party document.

Salinas, who took office Dec. 1, will head “what could be the most difficult administration of the post-revolution era: lacking prestige…subjected to popular discredit,” stated the report, published by the weekly news magazine PROCESO a few months after the election.

In November, the United States granted Mexico a $3.5 billion short-term loan to deal with revenue losses caused by the drop in oil prices. Analysts say the loan, the largest ever to a debt-burdened nation, reflects a U.S. concern that if Mexico’s economic situation worsens it could affect Salinas’ ability to govern.

“The perception here is that anything that can be done for Salinas is necessary and he needs all the help he can get,” said Adolfo Aguilar Zinser, a Mexican political analyst at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, in Washington. D.C., and Cardenas sympathizer. “The overall concern is that a sequence of events could have undermined the political and social situation in Mexico.”

Analysts trace the roots of the current political crisis to 1968 when the government repressed a movement led by university students that challenged the authoritarian PRI government. The movement, which called for basic political reforms, culminated in a massacre on Oct. 2 when troops fired on a peaceful demonstration in Mexico City, killing an estimated 300 people. The system has never been able to recover the prestige it lost 20 years ago.

“The first manifestation against the PRI was in 1968,” said Gonzalez.

Fear of further repression following 1968 and the absence of an organized opposition hindered further immediate challenges to the government.

Since Mexico entered a profound economic crisis six years ago resentment and anger towards the system have mounted. In the more conservative northern border states, the PAN has gained support.

But since Cardenas separated from the PRI just over a year ago, he has gained unprecedented support for an opposition party, drawing people who do not sympathize with the conservative PAN and have repudiated the PRI.

The exodus of Cardenas and other PRI members “has caused tremendous damage to the party, it’s taken away a lot of force and this has profoundly affected the Mexican political system,” said Gonzalez, adding, “The party leadership should have done everything possible to prevent the (democratic) current from leaving.”

In the months following the presidential election several PRI members have deserted to the Cardenas camp. In turn, the PRI has captured a handful of Cardenas supporters. Political observers, though, estimate the PRI converts were paid a stiff price for their conversion.

State elections in the oil-producing state of Tabasco last November, considered the first test of whether the government is committed to political reform, cast doubts on the sincerity of promises for change.

Official results showed PRI gubernatorial candidate Salvador Neme Castillo sweeping the election with 78 percent of the vote amid numerous irregularities and charges of fraud by the opposition.

“The PRI is saying that we will only permit democratic concessions where we graciously permit them. That is not political reform,” said Aguilar in a telephone interview.

“What happened in Tabasco is proof that there is no desire for democratic change,” said Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, the FDN gubernatorial candidate who until a few months before the election was a PRI activist.

Analysts predict that if Salinas and aides are unsuccessful in their attempts to reform the PRI there will he more desertions to the Cardenas front.

Gonzalez was a member along with Cardenas of the dissident PRI group known as the democratic current that two years ago tried to initiate reforms within the party. When Cardenas and others broke with the PRI last year Gonzalez chose to remain because he said he preferred to fight for reforms within the party.

Until September Gonzalez headed a PRI committee designed to pursue political reforms. The so-called modernization committee “hasn’t functioned,” said Gonzalez, “because in the commission of about 50, I can assure you that not even five really want to change.”

More recently Gonzalez heads a new group within the PRI called the “critical current” of which he appears to be the only active member.

Antonio Tenorio Adame was a PRI activist for nearly two decades, most recently as a federal deputy. Shortly after the July election he joined the Cardenas front.

“The PRI has stagnated and people have deserted,” Tenorio said in an interview, adding that since the July election the Cardenas front is a political alternative. The Cardenas front and the PAN won 240 of 500 seats in the chamber of deputies. In addition, the Cardenas front won four of the 64 Senate seats, marking the first time the opposition is represented in the Senate.

“There is an alternative. Now you can abandon the PRI and continue your political career,” said Tenorio.

In the months following the election, Cardenas has continued to muster support for the opposition. In December, he accepted several invitations to address think tanks and universities in the United States.

The results of the Tabasco election, however, were considered a setback for the Cardenas-led opposition. “Tabasco is going back to the notion that the PRI is invincible, that there is no opposition,” said Aguilar. “This is not good for the opposition and it’s not good for Salinas. It demoralizes the people, raises questions about the opposition and proves it is not an easy road. That certainly hurts opposition, their margin of credibility and confidence,” he added.

“The government and the PRI are doing everything possible to divide the opposition, the Cardenas Front as well as the PAN,” said Bartra, who added that any reforms within the PRI will most likely be carried out only if there is a continued threat from the opposition. “If Cardenas’ movement is weakened it will be difficult to achieve a democratic transition. The good will of Salinas and Camacho is not enough to move towards a democratic transition.”

The formation of the PRI did promote political stability in Mexico, but it also spawned a large network of patronage and hindered the development of opposition parties.

Analysts both within and outside the party say the PRI’s fundamental failure is that it has no grassroots organization, that it has been run more like a corporation with decisions imposed from the hierarchy.

“In the party there really is no internal democracy,” said Gonzalez.

Most PRI candidates are selected by the PRI leadership, a process known as the “dedazo.” Salinas was directly chosen by de la Madrid and the absence of broad participation in the selection of the PRI presidential candidate was the catalyst for Cardenas’ and the Democratic Current’s break with the party.

Perhaps the biggest hindrance to political reform comes from within the PRI, where many party officials refuse to risk losing the power they wield through corruption and patronage to lead the way for a more democratic regime. In PRI vernacular these old-guard members are euphemistically referred to as the dinosaurs.

“To reform the PRI would mean a loss of power and this would interfere with the interests of the dinosaurs,” said Garrido.

“There are politicians within the party who are opposed to change …political leaders who have power in municipalities and states and who for many years have taken advantage of the lack of democracy in the party to secure political positions,” Gonzalez said.

Often the only way to insure participation at PRI political rallies is to “acarrear” or haul people to events in return for wages or party favors.

Melquiades Cordoba Martinez, an unemployed oil worker and a group of friends attended one of Tabasco PRI gubernatorial candidate Salvador Neme Castillo’s rallies prior to the November election. He said attendance at PRI rallies was required by the petroleum workers’ union leaders to secure work in Pemex, the state oil monopoly.

“You have to participate to get the signature,” Cordoba said as he stood in the blazing 90-degree Tabasco heat, referring to the union’s sanction for employment. “Do you think I would come here for free?”

When asked if the PRI condoned union pressure to insure political participation, Roberto Madrazo. PRI Senator from Tabasco said, “The petroleum workers are helpful for the strengthening of the party.”

Neme said the petroleum workers union leaders are “untouchable.”

“People have belonged to the PRI for personal interests not for ideological reasons,” said Garrido. “With the electoral disaster they (PRI) realize that what they should have developed is a (grass roots) structure of citizens not ‘acarreados,’” he added.

In lieu of grassroots organizations the PRI is structured around three sectors that are supposed to represent workers, campesinos, bureaucrats and professionals.

Within the ranks of the sectors however, there are growing signs of nonconformity with the PRI.

At a meeting of the Mexican Workers Confederation, CTM, a pillar of the labor sector, a few months after the election workers chanted Cardenas’ name. At another meeting of the national teachers union several members also chanted Cardenas’ name in the presence of then President de la Madrid.

In November rival unions clashed in a dramatic shootout in the lobby of one of Mexico City’s most exclusive hotels in an argument over which group had the right to a labor contract there.

Two people were killed in one of the biggest public displays Of union violence in recent years. Members of the CTM stormed the hotel, set fire to carpets, broke windows and attacked members of the Revolutionary Confederation of Workers and Campesinos, CROC. Gunfire was exchanged.

Just a week before the shootout at the Hotel Presidente Chapultepec, two were killed in another union clash in Acapulco.

The violence is interpreted as a message to the new government that the union interests cannot be ignored.

“What’s at issue is the fight for power in the next six years,” one PRI official who asked not to be identified, said of the labor dispute. “The unions are saying that they have people capable of doing whatever is necessary to protect their interests. It’s going to be more and more difficult to maintain order in the CTM ranks.”

Elections results inevitably show sweeping PRI victories in the countryside. But a closer look at the rural Mexico show the PRI’s support there is limited, according to analysts.

“Politically the PRI has stopped attending to the interests of the campesinos and the foothold of the PRI in the countryside has deteriorated,” said Bartra, who has studied political participation in rural Mexico. “Without fraud the PRI can’t win in the countryside,” he added.

“The countryside is passive and their votes are hijacked,” said former PRI member Tenorio. “The bal1ots arrive in the communities and they are all returned in favor of the PRI. It’s just a transaction,” he added.

In many ways, analysts say, Salinas is a hostage to the PRI old-guard, because they secured his presidential victory and assure participation, one way or another, at PRI events.

“Without the dinosaurs Salinas would not have won the election,” said Bartra. “Primarily because they are the ones that organize the fraud and control the population.”

The dinosaurs have hardly disguised their disdain for the political reforms Salinas and aides propose. The opposition victories in July over PRI candidates was viewed unfavorably by many old guard PRI members who are not used to losing.

“Instead of battling the opposition (the PRI) has been turning over power little by little,” said labor leader Fidel Velazquez in an acerbic speech while then PRI leader Camacho stood at his side in September. “From now on we will…attack the enemy as best suits our interests and not as it suits certain politicians in the country,” he added in a thinly disguised attack on Camacho and PRI members who want to reform the party.

Gonzalez and other PRI members who support party reforms say the old guard will simply have to accept change in order to salvage the party.

“A lot of Priistas have to learn the rules of democracy. There will be resistance to reform within the party but I don’t see any choice,” said Farias. “The party will have to change…We can no longer select candidates because they are someone’s friend. From now on we have to have qualified candidates. It’s quite a shaking up for us.”

Also at issue is whether the PRI leaders recognize the extent of the party’s crisis.

“To hide the facts or ignore them in the analysis hinders taking the necessary decisions to correct decisions and get back on the right path,” Gonzalez said.

Some fear that to prevent further party losses the government will again resort to fraud that could spark violence and ultimately lead to a far more authoritarian government than Mexico has seen in recent decades.

“It’s possible that the government could opt to close off possibilities for democratization and to clean up the electoral process,” said Bartra.

Analysts and PRI members, such as Farias and Gonzalez, admit the resuscitation of the PRI is an awesome task.

“The PRI has a lot of work to do. A lot of people voted against the PRI, against the ‘dedazo,’” she said.

“The crisis in the party is so profound that at times I think that it’s too late to attempt a democratic change,” said Gonzalez, pausing in a moment of reflection, then adding abruptly, “However, I haven’t lost my optimism and I’ll continue fighting for change.”

Others are less optimistic about the PRI’s future.

“What Salinas would like to accomplish is contingent on whether or not he has a real party,” said the PRI official.

“The PRI is going to fall like a house of cards in many places,” said Bartra.

© 1989 Suzanne Bilello

Suzanne Bilello, a freelance writer, is researching the effect of the events Of 1968 on Mexico’s political future.