MEXICO CITY-In the wake of last July’s controversial presidential election, center-left opposition leader Cuauhtemoc Cardenas could readily muster 200,000 supporters to fill Mexico City’s central plaza to rally against the ruling party.

But as the memory of irregularities and fraud charges stemming from the July 6 election faded, Cardenas and his followers drew substantially smaller crowds and shifted their strategy away from protests to the difficult task of ordering their own political house.

In an attempt to unite under one umbrella the numerous political factions that supported his unsuccessful presidential bid, Cardenas is trying to form a new political party.

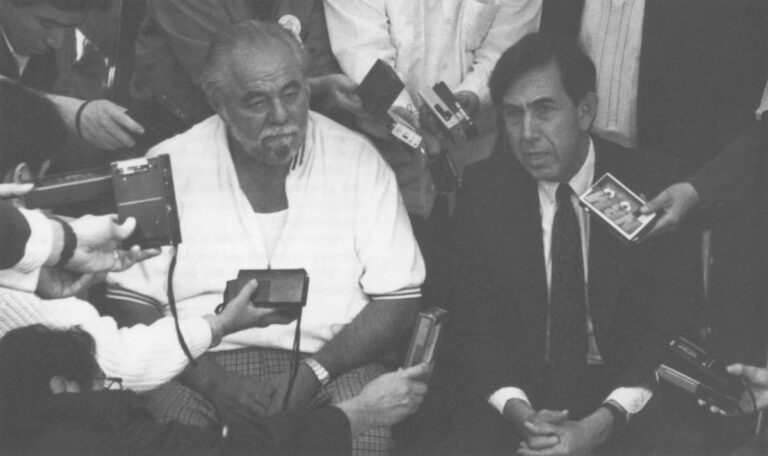

In the chilly days before Christmas, Manuel J. Clouthier, center-right National Action Party, PAN, candidate for president launched a brief hunger strike to protest charges of fraud in state elections in December.

The corpulent Clouthier held a vigil that bordered on the melodramatic in a tent pitched near the Monument to Independence on Avenida Reforma in the center of the capital.

Since July, the opposition has retreated to Mexico’s political trenches, waging smaller battles and publicity stunts, struggling to continue the challenge to the ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party, PRI, that erupted in July. Amid numerous irregularities and charges of fraud, PRI candidate Carlos Salinas de Gortari won that race with just over 50 percent of the vote. Cardenas came in second with just over 31 percent and Clouthier received 17 percent.

The opposition’s withdrawal from the political limelight comes at a time when national and international attention are focused on the policies of the Salinas government, particularly its management of the country’s huge $106 billion foreign debt and its moves to modernize the beleaguered Mexican economy.

Yet despite earlier predictions and historical patterns, the opposition has not gone away and the public discontent with the ruling party that emerged on July 6 has not faded.

“July 6 is behind us, we voted, now the real politics have to begin,” said Samuel I. del Villar, a former government official and political analyst who resigned from the PRI last year. Del Villar and other analysts say the political regrouping of the opposition is a long term process the success of which will be determined with time.

“I think the opposition will continue to grow. What is happening now is normal,” said Juan Molinar, a political analyst at the National Autonomous University, UNAM, in Mexico City. “It’s not as fast a process as some people would like.”

The immediate issue is to what degree Salinas, who took office on Dec. 1, will fulfill his promise to promote political reforms that could, in the course of his six-year term, transform his authoritarian one-party government into a more democratic regime. Salinas, an economist educated in the United States, faces strong opposition within the PRI to opening political participation to the opposition. The PRI has ruled Mexico without interruption for 60 years. Since Mexico entered an economic crisis in 1982, discontent with the PRI government has posed unprecedented challenges to the ruling party at the election polls, the most serious of which was the disputed July presidential election in which Salinas was elected with the lowest percentage of the vote ever for a PRI presidential candidate. He consequently took office with the weakest political mandate for a Mexican president since the ruling party was founded.

The initiative for political reform must come from the Salinas government. And in the early months of his administration Salinas has sent out contradictory messages on whether or not he will open the political process.

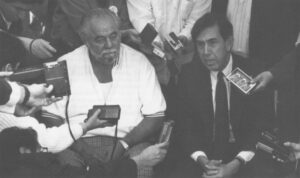

In what could become a significant move to modernize the political system, dozens of leaders of the petroleum worker’s union were arrested in January on charges of illegal arms possession and tax evasion. Among those detained were top union heads Joaquin Hernandez Galicia, known as “La Quina” and Salvador Barragan Camacho. They were considered untouchable because of the power they wield over the 125,000 member union which represents most workers at PEMEX, the state oil monopoly.

The move was praised as a potential step towards political and economic reform. By attacking the hierarchy of one of the most corrupt, venal and powerful unions, Salinas paved the way towards making PEMEX more competitive in international markets. Union corruption, particularly through lucrative subcontracting, contribute to PEMEX inefficiency.

Moreover, the dismantling of union power and corruption is considered essential if Salinas is to realize a modernization of both the PRI and the Mexican economy.

“If the PRI is going to modernize it has to get rid of the corrupt union structure,” said Gabriel Szekely, a political analyst at the Center for U.S.-Mexico Studies in San Diego.

It remains to be seen if Salinas’ actions will be followed up with concrete changes in the corrupt union structures at PEMEX as well as in other unions. Salinas had long been at odds with the PEMEX union hierarchy and during the presidential campaign La Quina is believed to have instructed his workers to vote for Cardenas, lending a strong undertone of political vengeance to Salinas’ actions.

At the same time, the detention of the petroleum workers in January was executed with military force, leaving many wondering, what other message Salinas wanted to deliver. The blatant show of force–a bazooka was fired into La Quina’s well guarded home in Cuidad Madero–was interpreted as a signal that the government is prepared to use strong arm tactics against the enemies.

Shortly after the PEMEX union leaders were imprisoned, Eduardo Legorreta, head of one of the most prosperous brokerage houses in Mexico, was also arrested and charged with fraud. The move was another political coup for Salinas.

“Salinas has the reputation of being a technocrat and he has proved to be the best politician since Lazaro Cardenas. He’s a tough one,” said Sergio Sarmiento, a columnist with the newspaper El Financiero, equating Salinas’ savvy of Mexico’s most revered president and father of political foe Cuauhtemoc Cardenas.

Doubts about Salinas’ commitment to political reform were raised when Salinas appointed to key government posts several old-guard political leaders known for their opposition to opening the system.

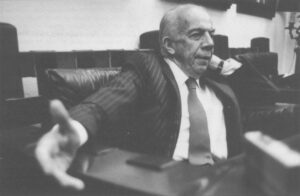

“Based on government appointments of people who are opposed to democratic measures we can interpret that they are not inclined to open the system,” said Lorenzo Meyer, historian and political analyst at El Colegio de Mexico, a graduate school and think tank in Mexico City.

Meyer and others single out the appointment of Fernando Gutierrez Barrios, a former director of the national security police, which in 1968 repressed thousands of demonstrators who challenged the political system to head the Interior Ministry which controls the electoral process. Gutierrez also headed an anti-insurgency drive in the 1970s during which scores of political dissidents disappeared.

“The opposition has come to the conclusion in the past months that there is no political opening, no intention for better rules of democratic participation. There is a clear indication that methods are in place to close the political process, not open it,” said Adolfo Aguilar Zinser, political analyst at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington and Cardenas sympathizer.

Continued pressure by the opposition and channeling of public discontent, however, is considered vital if any political reforms are to occur, according to political analysts and members of the PRI who Support an opening of the political system.

“The degree of change that will occur depends on the mobilization of the population. If there is no social pressure for change it would be the most unfortunate part of this process. Never have we been close as we are now towards pushing for democracy,” said one PRI official who asked not to be identified.

The immediate challenge to both the PAN and Cardenas’ coalition, the National Democratic Front, FDN, is to fight in Congress for a new electoral law that would promote fairer elections. Under the present law the PRI-controlled government conducts and qualifies the entire electoral process.

“With the current law we can’t have clean elections,” said Jorge Alcocer, a federal deputy for the Mexican Socialist Party, PMS, one of five major political groups that comprise the Cardenas front.

In addition, both parties are gearing up for 14 important state elections that are to take place between July and December this year. They will test their ability to rally support against the PRI and the Salinas government’s commitment to fair elections.

Turnout in local elections in Mexico is traditionally lower than in national races. Moreover, voter indifference may increase because of disillusionment stemming from the July 6 election.

“Most people don’t believe in the political process anymore. Fraud shrinks voter participation. If the government is not willing to make concessions, why vote?” says Aguilar.

The most important elections are in Baja California Norte, whose capital is Tijuana, and Michoacan, two states Cardenas carried in the presidential election. Voters will choose local officials in both states as well as the governorship of Baja California Norte. In addition, local elections in the PAN stronghold of Chihuahua also are to be held in July.

Since the pivotal July election the political opposition in Mexico has been cast in a new role. Historically the opposition, including the PAN as well as smaller leftist groups that now support Cardenas’ coalition, were obliged to negotiate small victories with the PRI government.

“Before if you gave up your struggle the system would show its generosity with you in other areas,” said Aguilar, explaining that capitulation would result in either increased government subsidies or recognition of isolated political victories.

“There was a general acceptance by the leadership that it’s better to recognize defeat even if there was fraud in order to consolidate other areas. There were terms of engagement,” Anguilar said.

But since July, the unwritten rules of Mexican politics have changed, say Aguilar and other analysts.

Both the PAN and the FDN so far seem unwilling to capitulate to the government in exchange for limited victories. The PAN has met privately with Salinas but calls the meetings “dialogues” to pressure the president directly for political reform.

Some members of the Cardenas camp have criticized the PAN for meeting at all with Salinas.

Earlier this year a photograph of Salinas reaching out to embrace Clouthier’s hand adorned the front pages of national newspapers.

“The illegitimacy of the origin of this government doesn’t prevent it from being the government,” said PAN official Carlos Castillo Peraza, defending the party’s meetings with Salinas. “It would be absurd for the only role of the opposition for six years would be to say the government is illegitimate. We have to find a way to change things.”

The PAN wants to be realistic,” said Meyer. “Their position is that Salinas is the one that controls the political apparatus and it doesn’t make sense to ignore it. They saw in July that they are clearly the third political force and in the fight for influence, negotiation is better than confrontation.”

The PAN also decided this year for the first time to accept government funds. Castillo said the party previously refused the subsidies because it feared depending on a precarious source of income and chose to build its coffers with independent resources.

The two opposition fronts, although representing diametrically opposed constituencies, have agreed to join forces against the PRI in efforts to secure a new electoral reform law this year in the Congress.

“We are going to fight for a significant electoral reform,” said PAN leader Luis H. Alvarez.

At the same time the opposition is rallying support for a new electoral law and gearing up for the July elections, Cardenas faces the daunting task of forming a new political party.

It is unlikely Cardenas will be able to convince the five political groups that currently comprise the FDN to abandon their independent registration and join a new party. What’s at stake for these parties, some of which have reputations for being easily coopted by the government, is the loss of control of government funds provided to them under the current electoral law.

In fact, only two groups are actively supporting the formation of the new party, the PMS and the Democratic Current which is comprised of Cardenas and other renegade “Priistas” who abandoned the party in late 1987.

“Our first task is to create a new party,” said Alcocer.

“There is a lot of infighting but the party will be created,” says Aguilar.

The disagreements within the FDN over the movement’s future illustrate the divisions within the Cardenas front. Infighting among the left in Mexico has been one of the obstacles that has prevented it from becoming a viable political force. And it is uncertain what the outcome of the current disputes within the Cardenas front will be.

“The opposition could be in a period of reconstruction or in a stage in which the internal strife becomes so strong that they could lose everything,” said Meyer.

“The opposition has weakened because of its internal disputes. Divided they are not going to advance,” said Raul Trejo, a political analyst at UNAM. “The first thing Cardenas has to do is refine his internal structure.”

“The only solution is to try and form one party. There are many conflicts,” said Cuauhtemoc Sandoval, a Cardenas activist. “We need more organization and we need to work harder.”

Cardenas, the son of Mexico’s most revered president, Gen. Lazaro Cardenas, was a member of the PRI until a group of dissident PRI members broke with the ruling party because it disagreed with the economic policies of the PRI government. Since Mexico entered a profound economic crisis in 1982, first President Miguel de la Madrid and now Salinas have pursued a drastic reordering of the economy that has come at enormous social costs. Cardenas’ political position, however, has yet to advance beyond his ideological opposition to the PRI government policies.

“It is urgent that the FDN come up with programs,” said Luis Javier Garrido, a political analyst at UNAM. “They have organizational problems that make them look like rookies.”

Analysts agree, though, that what Cardenas has amassed is an opposition movement that is without precedent in modern Mexican history.

“No opposition has ever represented such a diverse, large cross section of the country,” said Aguilar. “The rules of the game changed because of the sheer size of the opposition.”

“Cardenas is a political actor that can’t be ignored,” said Meyer. “Cardenas is saying, ‘Give us time and with time we will create a movement that will prevent the government from functioning and fraud will be more difficult.’”

Meyer notes that previous attempts to challenge the PRI by groups that broke off from the official party were unsuccessful and the movements themselves disappeared after electoral defeats.

“Cardenas is not disappearing,” says Meyer.

At the same time the PAN, which this year celebrates the 50th anniversary of its founding, has, since the July election, consolidated its membership.

While the opposition wages its own internal struggles and plans future strategy, it will be looking for signs as to whether Salinas and his government will promote political reform.

“The government will have to prove with action that it is willing to change. It’s too early to say if they are going to act in good faith,” said Castillo of the PAN.

What the opposition fears more than anything else, is that the government will resist opening the systems for fear of losing its hold on power, potentially leading the country to confrontation.

Aguilar noted, “There is clamoring for change. You have a growing discontent and you don’t see how the opposition will be able to transform this into political participation if the government is preparing to build a repressive wall.”

©1989 Suzanne Bilello

Suzanne Bilello, a freelance writer, is researching the effect the events of 1968 had on Mexico’s political future.