Text and Photos by Maggie Steber

In Haiti, it is said that when you look at a man, you see death standing next to him. Personalities, dates and methods change, but there is always one sure factor–and that is death.

It is as much a part of life as living. Because Haitians have had to deal with so much death of so many natures, they have developed a sort of shared cultural psyche, borne of the frequent turn of political turmoil and the much misunderstood voodoo religion.

To understand Haiti, one must see the mystery that stems from this combination of paradise on earth and gateway to hell, and history is the key.

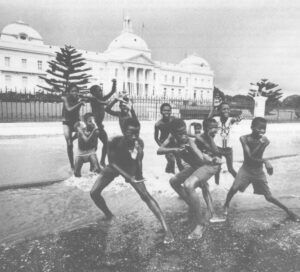

African slaves were ripped from their lands, beaten into servitude, and finally rose up in revolt in Haiti to become the first free black republic in the world. The significance of this one act alone, which terrified all colonial governments based on a slave economy, changed the course of world history.

For the first time, slaves, who far outnumbered their masters, rose against them and slaughtered them. It was big news in every paper in the United States and in Europe. But it also cost thousands of slaves’ lives and seemed to set the stage for an epic drama that was laced with violence and death.

Following a succession of more than thirty-four emperors, kings and presidents since 1804, violence has become a tradition in Haiti.

It is the one master from which the Haitians will never be free.

It was a Sunday like any other in Port-au-Prince as people arrived for mass last September at St. Jean Bosco, a progressive Catholic church, whose congregation was made up by residents of the nearby slum of La Saline. It was a Sunday like any other except that young people from the church youth corps stood at the front gates and checked everyone who entered. Inside, young men posted themselves at every window and door and kept vigil. And finally, as the mass be-an, instead of entering from the back of the church as he usually did, the priest, Father Jean-Bertrand Aristide, entered the modest cathedral through a side door. The precautions had been taken after the church had been attacked twice in the previous week by groups of rock-throwing men as the church youth corps held special mass services.

As was customary, songs about liberation preceded the mass. The notes of the final song still hung on the air. Father Aristide said a prayer and rang a small bell to signal the commencement of communion. He had lifted a gold chalice toward the heavens to receive a holy blessing when suddenly, a rush of commotion from the back of the church stilled the diminutive priest.

Outside, in front of the Church, a group of men were bashing parked vehicles with huge sticks and hurling stones through the windows, which burst with loud bangs. Inside the church, some people began to cry out in panic but they were hushed by young people in the center of the congregation who broke into a hymn and raised their fists into the air.

In the next moment, there was a terrible crash at the main door of the church as the gang of men broke through. Between twenty and thirty men ran in, waving pistols and shooting into the air. They began hacking through the crowd with machetes and clubs and knives. As soon as the men crashed through the door, a group of youths surrounded the priest, who stood frozen at the altar. They lifted him off his feet and ran out the door into the courtyard and towards his two-story residence.

Meanwhile, inside the church, there was tremendous panic as screaming parishioners scrambled to escape the bullets and terrifying blows of machetes. The attackers, who wore civilian clothes and red armbands to identify themselves from churchgoers, were “ti macoutes”, henchmen who carried out the murderous deeds of the “gros macoutes”, men considered to be evil powerbrokers who operated outside the law in Haitian society. The men swooped down on the people in the church, regardless of sex or age. The old wooden pews made loud crashing sounds as people clamored over them or tried to hide beneath them for safety. But there was no safety and the men worked their way through the church systematically slashing and beating and shooting.

The men killed as many as twelve people and wounded over seventy, including a pregnant woman who was stabbed in the stomach. As they reached the altar area, the assailants blocked all escape except through a small door where a crowd of worshippers seemed stuck by panic. People who couldn’t get out of the door were caught by the men. Four thugs surrounded one young man who they beat to the floor with clubs until his battered body lay still. A woman, in a panic, ran right into one of the attackers who wielded a machete. He grabbed the woman’s shoulder and raised the machete into the air but the woman pulled away with great force so that the man lost his grip on her shoulder. He held onto her dress, however, and it ripped down to the small of her back as she ran for the door and out of the church.

Even after the worshippers escaped the church, they were caught in the walled church courtyard. Outside the wall, more than one hundred attackers surrounded the compound, according to witnesses watching from the slum across the street. Some people who tried to escape over the wall were caught and beaten or slashed as they leapt to the street. The shooting continued, accentuated by small explosions outside the walled compound. The parishioners thought the explosions were burning vehicles until they spied a column of black smoke rising over the church.

The men were burning down the church. They did more than that with their actions. By burning the church of the firebrand priest, who had repeatedly spoken out against government improprieties and violence perpetrated by the macoutes, they had effectively cut the tongue out of the voice of the people. The Haitians trapped inside the compound wept and cried out when they saw the smoke. Several young men ran for the church and managed to save a large wooden cross which they carried past bodies of several people who had fallen dead in the yard. Still others ran with a tall ladder to rescue people who had clamored up some stairs to escape into a storage room over the church. The people climbed down and several youths climbed up and began throwing schoolbooks and typewriters out of the windows until heat finally drove them away.

The attack continued for three hours. Those trapped inside wandered around in a daze or tried to help the wounded as the attackers peeked over the wall from time to time to shoot at the captive Haitians. Upstairs, in the priest’s residence, Father Aristide and several other priests were surrounded and guarded by the church youth corps, although there was no real way to lend protection. Downstairs, armed with a few stones, people prayed and organized themselves into small groups placed at intervals around the yard so as to see every part of the wall in case the attackers charged. The Haitians showed a courage that was stunning in the face of this death which threatened to be so violent and without escape. They had fought and they would die, some declared, for a dream. Saving it gave them a courage, at least for the moment, that outweighed the weapons that had been sent against them.

At last, the Haitian Army, which had stayed away during the entire attack, arrived at the church and demanded that the people traped inside open the church gates and allow them to enter. The Haitians did not want to open the gates because they feared their attackers were with the Army, but a priest arrived and convinced them it was safe. The gate was opened and the people were told to leave and go home quickly. Then the soldiers went upstairs and told all the youth corps and the priests, except Father Aristide, to leave. After reported torturous threats from some of the soldiers, Aristide was allowed to leave. He has remained in hiding and has received orders from the Vatican to leave Haiti. In December, the Roman Catholic Church issued an order expelling Aristide from his order of the Salesian brothers, accusing him of using religion to incite violence.

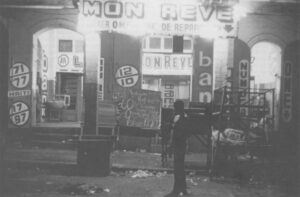

That week, two other progressive Catholic churches were burned in Port-au-Prince. The attackers went on national television to warn that they would be “reducing the congregations to a pile of corpses” in any church that took Aristide in or that preached against the government. The outlaws also raided the general hospital maternity ward in search of the pregnant woman who had been stabbed at St. Jean Bosco. They made all the women disrobe as they searched for the telltale wound. The woman and her unborn baby had been saved and hidden at a private hospital. The men came away empty-handed but with each action, the Haitian population was thrown into a desperate fear that made them cower behind the closed doors of their homes.

One week later, a coup d’etat staged by the lower ranks of the army deposed the government of Gen. Henri Namphy and replaced him with Brig. Gen. Prosper Avril. Gangs of citizens attacked the homes of the big macoutes, sending their owners into hiding. Some of the men who attacked the churches were caught and killed and their battered bodies were dragged to the street in front of St. Jean Bosco where they were burned until nothing was left but ashes. Violence begat violence. People in the slums said Death was watching from the sidelines as He collected the souls of the innocent and the guilty.

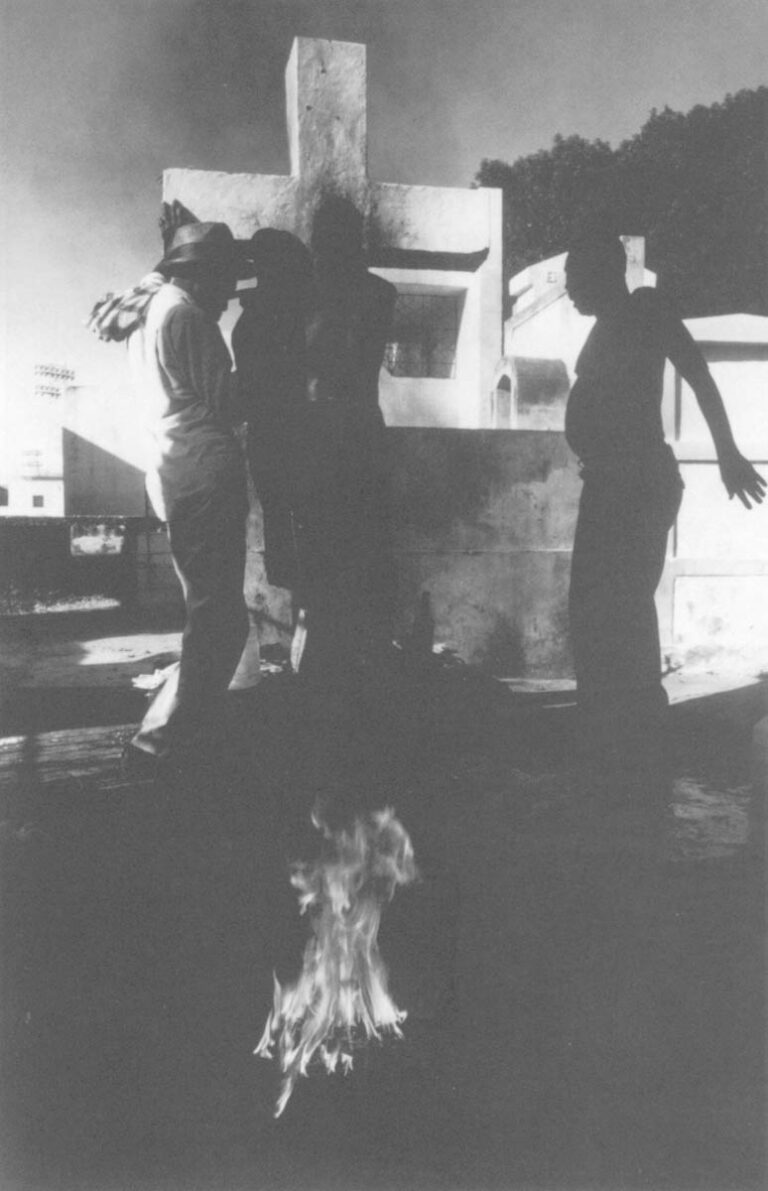

The soldier looked anxious as he paced back and forth in front of the tall cross of Baron Samedi, a voodoo spirit from the Ghede family which rules death in the voodoo pantheon of gods in Haiti. The cross of the Baron stood in a corner of the National Cemetery in Port-au-Prince and everyone in town knew of its existence because almost everyone in town had visited the place when they needed some prayer answered or some problem solved. Although he carried his rifle and wore his uniform, the soldier didn’t appear to be on duty. Instead, he awaited the arrival of an houngan–voodoo priest–whose aid he had enlisted to release him from some evil hand that held him gripped in illness.

The houngan was nowhere in sight but he had obviously been there earlier, because many offerings lay on the base of the cross that served as the altar to Baron Samedi. There was a gourd bowl filled with rum, holy water and a mixture of leaves from medicinal plants. Alongside that, a chicken stood with its legs tied so it couldn’t run away. Nearby, arranged very neatly, were two piles of charcoal and wooden sticks. Brightly-painted crypts surrounded the cross of the Baron and several paupers and gravediggers sat on them, watching the soldier pace and offering him words of comfort and assurance that the houngan would arrive soon.

And then, as if on cue, the houngan did appear. He was dressed in regular street clothes and wore a straw hat. He seemed quite normal except that his eyes were blazing red. He greeted the soldier and then sent him away, telling him to go buy a new pair of red underwear and to change his clothes so as not to offend the Baron. In the meantime, the houngan sang a song to the Baron and danced around the cross. Occasionally, he took a swig from a bottle of rum he held and poured amounts on all sides of the altar at the base of the cross until the soldier returned.

The houngan instructed the soldier to disrobe to his underwear. As the soldier did so, the houngan continued to dance and offer swigs of rum to the Baron, whose help he enlisted on the soldier’s behalf. Once the soldier had undressed, the voodoo priest poured the contents of the gourd over him and rubbed the leaves hard into the man’s skin. He took another swig of rum and spewed it all over the soldier who shivered and grimaced at the sting of the mixture. The priest picked the chicken up and rubbed it all over the body of the soldier as the chicken squawked a useless protest and flapped its wings.

Meanwhile, one of the gravediggers who was lending a hand in the ceremony had set the sticks and the charcoal on fire. The priest went into a total possession and his jerky dance took him all over the bare earth which surrounded the cross. He danced wildly and sang as he pushed the soldier against the cross, turning him front and back. The priest, possessed by Baron Samedi, ordered the soldier to remain there while he did his work. The soldier did as he was told but he looked scared. It was no wonder because the priest–as Baron Samedi–took on a new character. His eyes burned bright red from the possession and probably because of the amount of rum he had consumed. He sang a song that spoke of the Baron’s power over life and death and his kinship in the Ghede family.

Ghede is a dark figure who attends the meeting of the quick and the dead. He is the god of the dead but because he also attends the passage of all souls into the cosmic cemetery of the voodoo religion, he is considered to be the god of life as well. He is the repository of all the knowledge of the dead and thus, has great healing powers. He is also considered to be a sexual rascal and the lord of eroticism. He is implored on behalf of those suffering from love problems. He dances the dance of copulation and at ceremonies, often embarrasses the participants with his aggressive sexual behavior. Finally, Ghede and his cousin, Baron Samedi, are the ones who weigh the good and the bad of a man as he passes from the living to the dead. He is the one spirit no one wants to offend and so, he is lavished always with gifts and honors.

The singing of the possessed priest continued for some time until he shouted to the soldier to change underwear. The soldier quickly took off the old wet underwear and put on new red briefs. Baron’s preferred color is black, but red was required for the healing process. The soldier still stood next to the cross and shivered as the rays of the setting sun grew weaker. Finally, the priest told the soldier to get dressed. The soldier did so quickly. The priest, who was still possessed but in a calmer state, told the soldier to walk backwards away from the cross, to go and not to look back or he would drop dead. The priest handed the man a small ounaga–a charm bag–to hang around his neck. In return, the soldier handed the priest some folded money. Then he walked backwards until he disappeared.

The voodoo priest was still possessed by Baron Samedi and he spun wildly around until he bumped into a woman who stood nearby watching the ceremony. He grabbed her and spun her and danced the Baron’s sexy dance of copulation. The woman threw her head back and laughed because it was an honor to dance with death and it might mean that the Baron was giving her a blessing. The paupers who had sat on the nearby graves watched the earlier ceremony spellbound. But at this action by the Baron, they laughed and cackled and took great delight in the dance. Finally, before he released her, the houngan, still possessed, peeked into the breast pocket of the woman’s blouse and pulled out a few Haitian dollars. He cackled and released the woman from his grip. He turned and swooped his hat from the ground, put it onto his head and bowed, tipping the hat to the woman before he danced out of the cemetery and down the road.

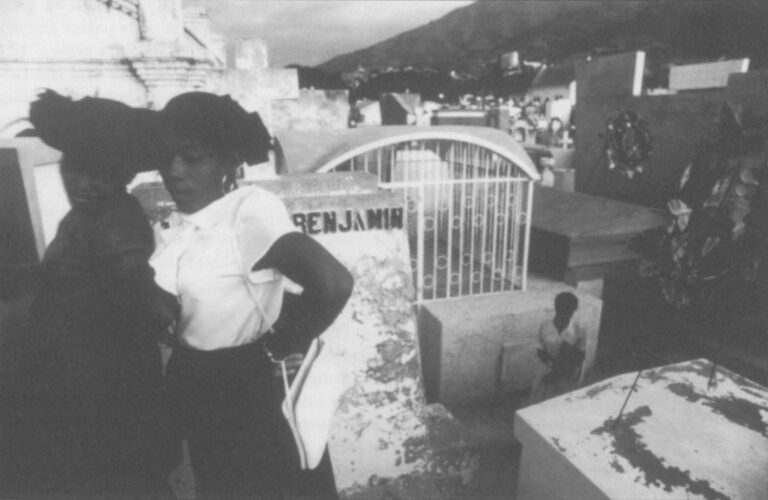

The family of Asson Vital gathered around his open coffin as the afternoon sun poured in through the open doors to lend some light to the cavernous St. Anne’s cathedral in Haiti’s capital. His widow wore a black dress and hat that is part of every Haitian woman’s wardrobe. His children–two daughters and four sons–sat next to their mother and shook hands with people who had come to pay last respects to their father.

Asson Vital was an unemployed carpenter who had been killed on election day, Nov. 29, 1987, at a polling station in Port-au-Prince when efforts to hold the first presidential vote in thirty years were halted by attacks from armed thugs.

A mulatte woman who identified herself as the employer of Madame Vital, a domestic worker, clucked her tongue as she told an observer about the man’s death.

“He had told his family he was going to vote in hopes of changing the country and changing life for the family. It was especially sad,” the woman continued, “because the school where Monsieur Vital had gone to vote was located on Ruelle Vaillant. It means street of the brave, you know. In Haiti, it is always the vaillant who are killed. The rest of us cowards hide in our houses because we have too much to lose. He had a lot to lose too, his family, his life, but he had no future if things didn’t change. He tried to change the future,” she said as she shook her head and smiled faintly.

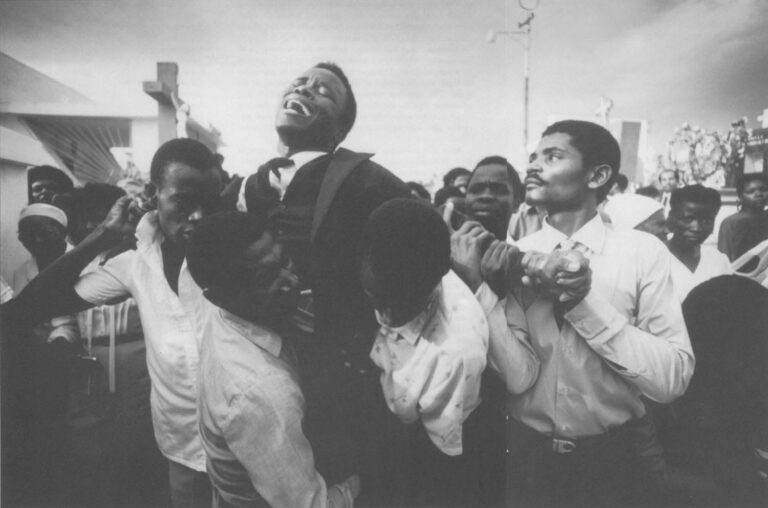

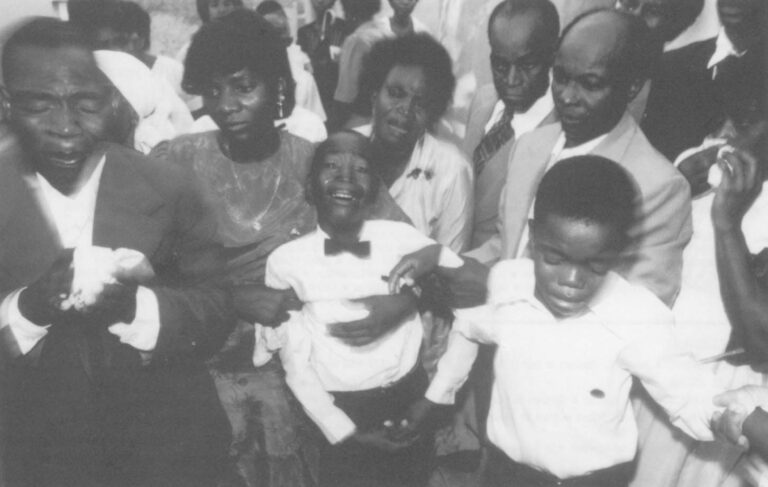

The church bells sounded and the coffin of Asson Vital was carried by his friends and family to the altar of the church where the priest held a funeral mass. Afterwards, the coffin was carried out to the front of the church and carefully placed into a black hearse. His family formed a parade behind the hearse. Preceding it was a funeral band of musicians, dressed in white shirts and black pants. They began to play funeral dirges as the parade marched slowly down Rue L’Enterrement–Burial Street–and finally, through the gates of the National Cemetery. As the funeral party passed through the narrow corridors between the above-ground graves, Madame Vital was suddenly overcome with grief and she flew into a fit. Friends grabbed her and held her tightly as she jerked and screamed. Her teenage daughter, affected by her mother’s emotional outburst, also fell into a fit that resembled a possession. Friends of the family carried the two women out of the cemetery and put them into a waiting car.

The rest of the family continued behind the casket of their father. Their cries were heart-wrenching. The youngest children–two boys and a girl–led the family to the crypt where an empty black hole gaped, waiting to be filled. An uncle picked each child up and swung them over the coffin in a farewell to their father and to prevent the father’s spirit from returning to haunt them.

After that, the family was led away. Several men dressed in dark suits stayed to smoke cigarettes and talk as the gravedigger put the final touches of cement over the hole that now swallowed the coffin of Asson Vital.

The gravedigger left and one by one, so did the men. Only one man remained and he knelt before the freshly-cemented crypt. He placed a small cake and a candle, which he lit, in front of the grave. “Food for the journey and for Baron,” the man said in Creole as a visitor watched from a few feet away, and he winked. He walked away and left the candle burning as the sky and the cemetery beneath turned black with the night.

©1989 Maggie Steber

Maggie Steber, a freelance photojournalist, is examining life in Haiti after Duvalier.