Text and Photos by Maggie Steber

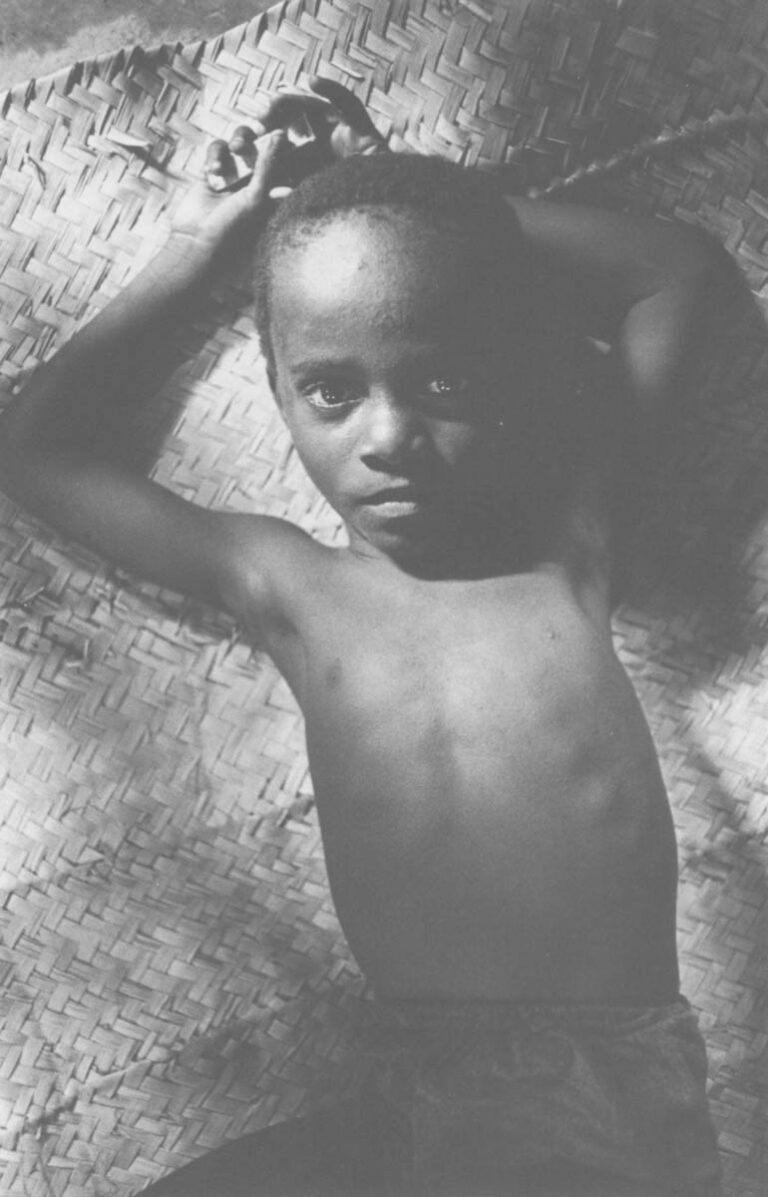

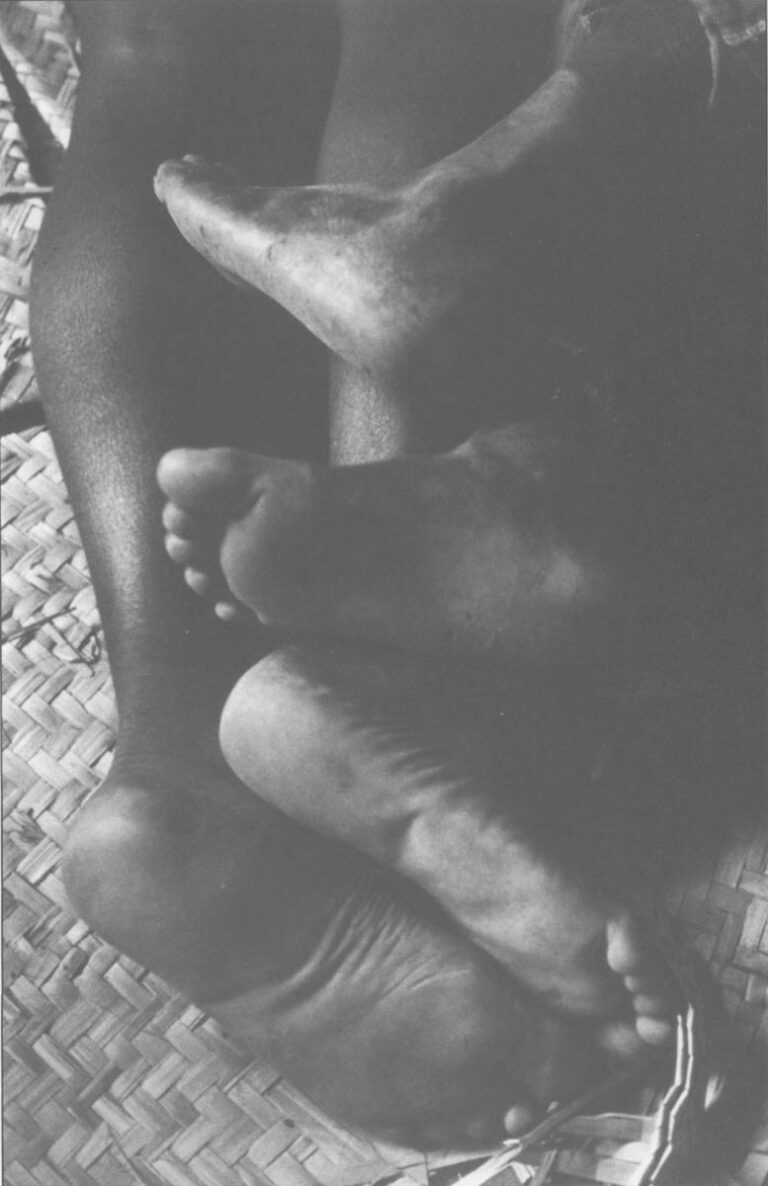

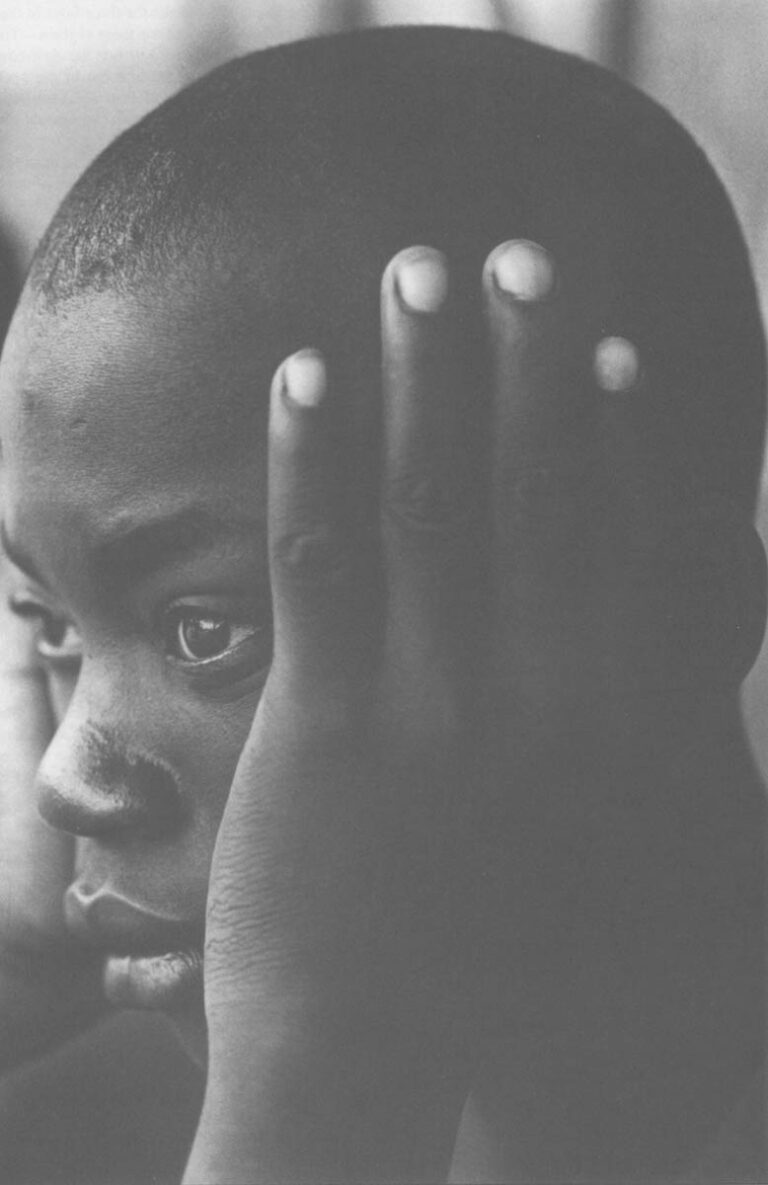

Life means these things to a street kid in Haiti: Sleeping on a hard concrete step or curb along the edge of a dusty road or rainy street; begging; washing cars for money; gambling at cards or dice; always trying to get a pair of shoes; fighting: being beaten; getting cut or having a toothache or fever; washing in sewers; hitching free rides on tap-tap trucks; sitting alone at night; hiding from bullets during shootouts by armed thugs; fleeing police; being thrown into the state-run reform school; being riddled with parasites; shaving your head with a bare razor to keep the lice out; playing kung-fu; being twelve and looking six; hair turning from black to red due to lack of protein; suffering from malnutrition; having no one to hold you.

Lesly’s eyes opened to the sound of the first pair of passing feet as a market woman with her wares hurried down the sidewalk toward the center of Port-au-Prince. He avoided opening them more than a crack so as not to disturb the escape from reality sleep had provided.

Everything was washed in the grey monochrome of the day’s first light. It was still soft, but rush hour was well underway at 6 a.m. and Lesly sat up at his curbside step without enthusiasm. He rose and walked over to a compact car parked by the curb and knocked hard on one of the windows. Inside, behind locked doors, five small boys slept. There was no air inside the car because the windows had been rolled up for safety. When one of the sleepy boys finally opened the door, a foul smell rushed out: the odor of sleeping boys mixed with the street.

Johnny was the first to fully wake and he stretched his small thin frame. His ribs stuck out, barely covered by transparent brown skin that revealed the most delicate veins. With his wide eyes and shaved head, he was a real attention grabber of a kid. It had worked for him and against him. He was at least twelve years old but he looked about five.

He sharply nudged the still-sleeping Alphonse Pierre with his elbow and Alphonse awoke with a start. Whatever complaints he wanted to register, Alphonse kept them to himself. He was a child of few words and the recipient of a lot of hard knocks.

The ensuing noise woke the three boys in the back seat to a fully conscious level and the three of them–Toni, Remy, and Cloris–sat up. They looked out the dust-covered windows that could not keep out the new day or the world that awaited them at the intersection of Portaille Leogane and J.J. Dessallines. There, at a traffic light, they would live by their wits washing windshields.

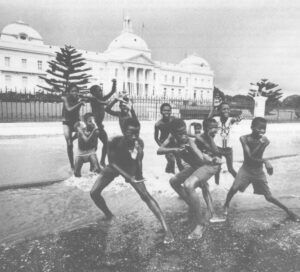

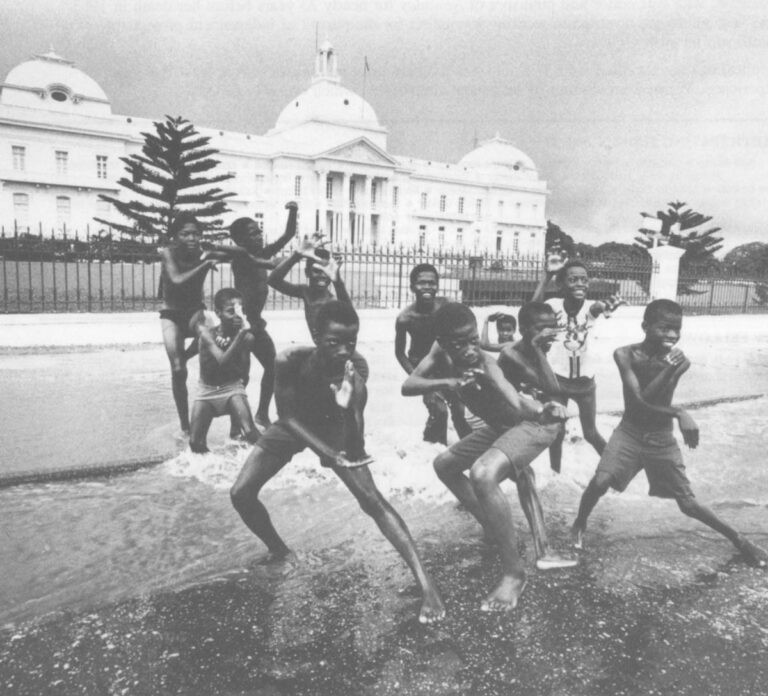

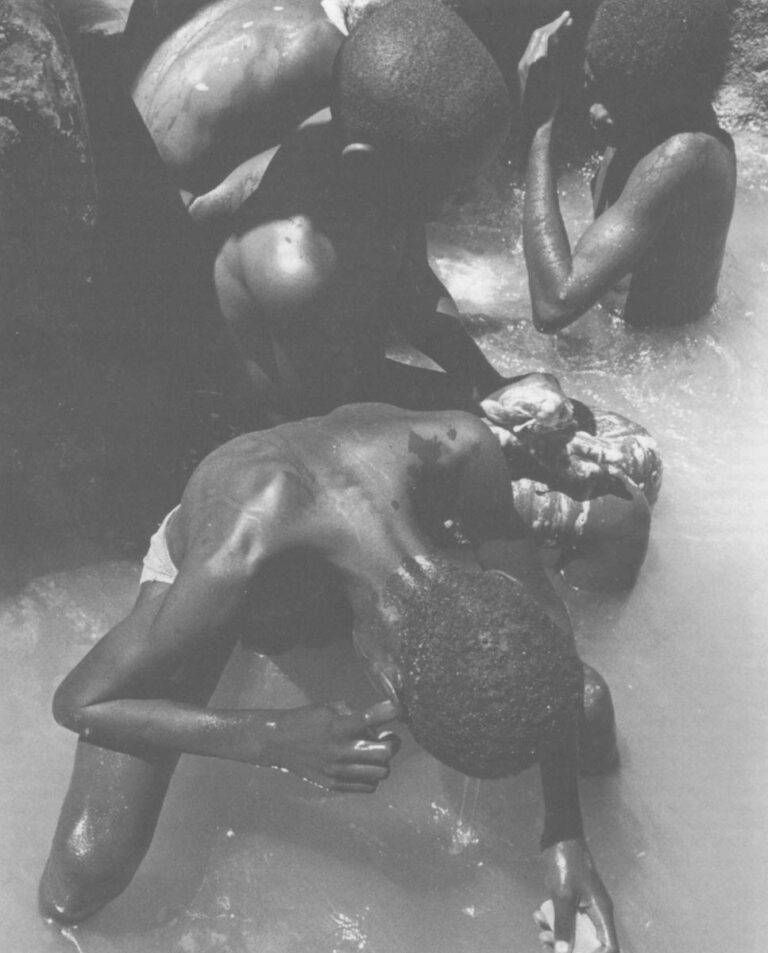

Johnny and Lesly had already pulled open the grating to the sewer and the other boys rushed to the corner where they all jumped into the running water below. They splashed water over their faces and bodies, shivering with the cold. They brushed their teeth with brushes and toothpaste that seemed to come from out of nowhere and pulled themselves back up to the street. Now they were ready for work.

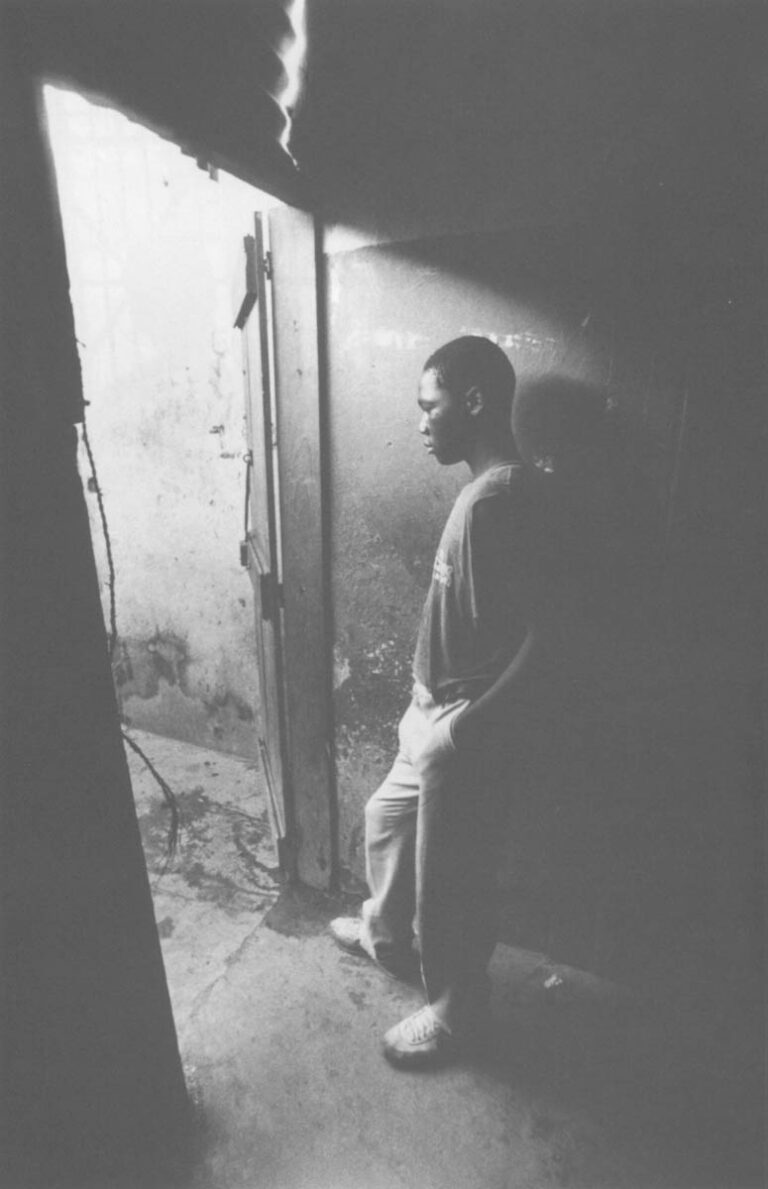

At the other end of the long main street of J.J. Dessallines, past several miles of markets, vividly painted buildings and the noisy business of downtown traffic, Dieucel stood alone in the doorway of a former voodoo temple in the slum of Tokio. He stared out at nothing in particular. Inside the building, it is dark and empty. Small holes in one wall allow only patches of light to pour onto the opposite wall. The 15-year-old boy-man was lost in thought, wondering what to do with himself this day.

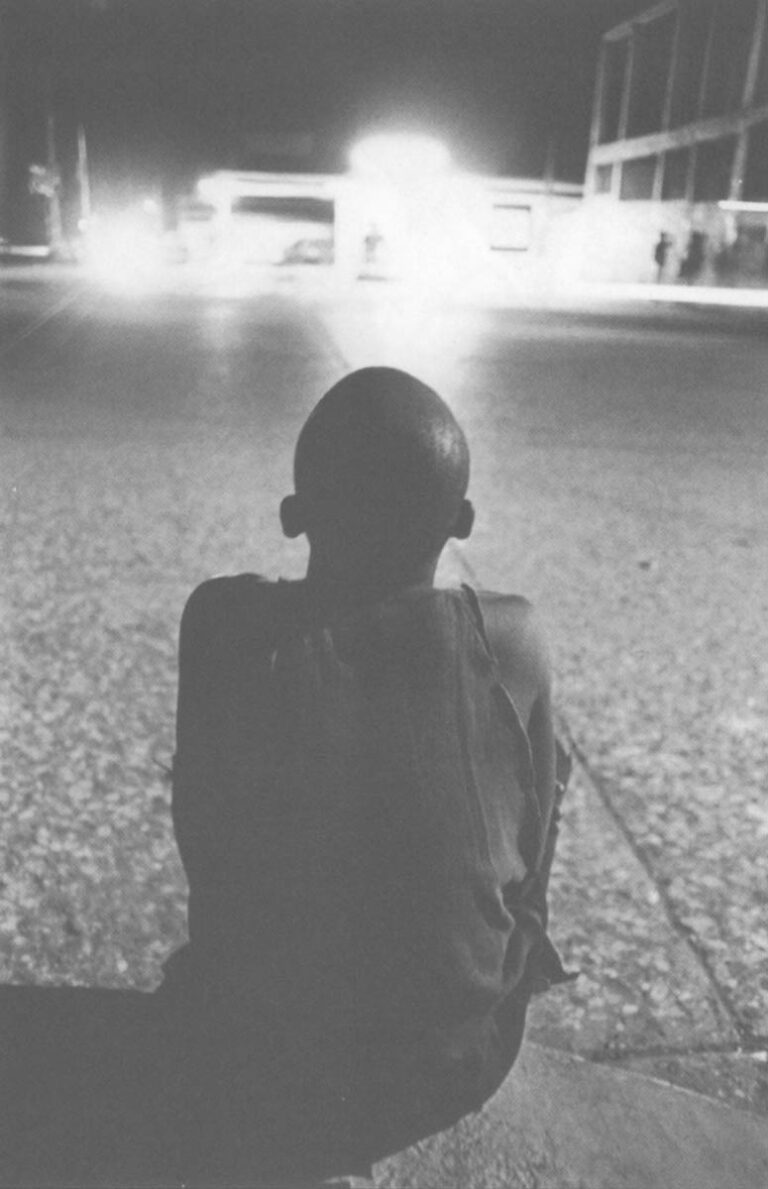

The other boys who share the slum house at night with Dieucel are already out at their traffic light. The light is a life-giving symbol in the boys’ individual and collective lives. At its feet, they can earn a living, begging from idling cars, washing windshields. Dieucel just doesn’t want to do it anymore. He would rather have a job. He knows he can no longer spend days begging and his appeal as a small boy vanished long ago. Physically, he is a man with man’s desires, but his emotions are still childlike. To forget his worries, he wanders through the slender alleyways between shanties of the slum and gets lost, finally, in the teeming streets.

Every day in Haiti, death, violence and finances cause at least 14 children to be abandoned, according to UNICEF. They are abandoned in the city and in the countryside, and most make their way to the nearest large urban center where there is more opportunity to earn a living off the street.

“The phenomenon of street kids isn’t unique to Haiti by any means,” says Ephrim Schluger, an urban expert for UNICEF, “but it has been nearly impossible to document. No matter how much we have wanted to, the institutional weaknesses in Haiti as well as the volatile political situation, has made the implementation of programs or studies next to impossible. Everyone knows there are thousands of street kids. You can’t miss seeing them on the streets.”

The only thing we have been able to determine is child labor in Haiti, where children are working in unsupervised situations. Their health and development are endangered and hampered. Our estimate is that the ratio of street kids to working kids is about 8 workers to 2 or 3 street kids.

Schluger reports that there also is a gender difference. Girls often tend to work or be put to work as street vendors, or placed in servitude with families as “reste avec” (French for stay with).

“The most interesting thing,” he continues, “is that child labor often means the exploitation, abuse, neglect and impairment of development for the younger workers. It’s worse than it is among kids who live on the street and learn to survive on their own through long-term systems or social groups. Very often the working child can only look at his day-to-day existence without envisioning any future for themselves outside of their confining work positions.”

Street kids also are not the vagrants they are accused of being, Schluger points out. “They work, as they must, to live. They are more independent in their work methods, more inventive in what they do and how they use their money. In a society like Haiti, they really are quite often better off, if one puts things on the very basic level of mere survival, than kids who are forced into labor at an early age. It’s a small microcosm of the Haitian society, embarrassing for the society and the government and because of that, research into their area has been practically nil.”

The Washington Office on Haiti reports that there are 40,000 homeless people sleeping on the streets of Port-au-Prince each night. UNICEF reports that 5,000 of them are the abandoned children that they know of, thrust into the streets to survive by begging, prostitution and petty crime.

Half the Haitian population is under 15 years of age and 50% of the death rate is made up by children under the age of 5.

More than 70% of children under 5 years suffer from malnutrition which affects their physical and mental development–and a nation’s future. Meanwhile, a square meal for a kid in the markets costs about 20 cents. Street kids suffer from little adult stimulation outside sex or abuse. Coupled with little book learning or practical sense, they are functionally retarded. It is such a dismal place for 90% of the Haitian population, that the United Nations has categorized Haiti as the “fifth world,” along with six other countries on earth where poverty is so institutionalized. The world body also has designated the lives of 50% of all Haitians as miserable.”

“It isn’t that money to change these problems has been lacking,” Father Jean-Bertrand Aristide, a Catholic priest in Port-au-Prince, explains. “Millions of dollars from both public and private aid groups has poured in since the regime of Francois Duvalier, for over 30 years. That’s one man’s lifetime, 30 years, in the streets, when there was money to help him eat and learn and work.

“But it never was really meant for us and that kind of money teaches the Haitian to be a slave to a bigger master. Instead, the money went and always goes into the thick greedy hands of the people who still maintain the bad habits of the Duvaliers.

“No one here really cares about these kids,” he continues. “Everyone here is doing his best just to survive. Anyone can see that after ten minutes in downtown Port-au-Prince. Most people think these boys are thieves,” he gestures out his office window at St. Jean Bosco where a group of streetboys sit huddled over a card game in the church yard. “They can only learn what samples are set for them. What does that tell you about our government and society?”

Renan Pierre, head of the Defense League for the Rights of Children in Port-au-Prince, explains that Father Aristide is one of the few people in Haiti who has taken up the cause of street kids.

Aristide, a diminutive man of only 34 years of age, is a cherished figure for his outspoken. antigovernment views, his “liberation theology” has made him a rebel in the Catholic Church and he is blamed by the government for any civil trouble that develops in the country. As a result of his notoriety, several attempts have been made on his life. One such attempt, in mid-August, 1987. occurred when Aristide was traveling by car with several other priests. Men armed with 9 guns and machetes at a roadblock demanded Aristide and threatened to kill the priests. Aristide was hidden and his fellow priests managed to thwart any violence.

“When a kid arrives in the capital or is thrown out of the family here, he knows he can go to Father Aristide and get something to eat or have a safe place to sleep. He talks about them in his sermons and on the radio. Every Sunday at mass, the altar is covered by street boys in their rags. They are the wards of Aristide,” Pierre continues. “But the boys sometimes pay a price for his patronage.”

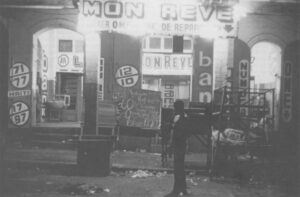

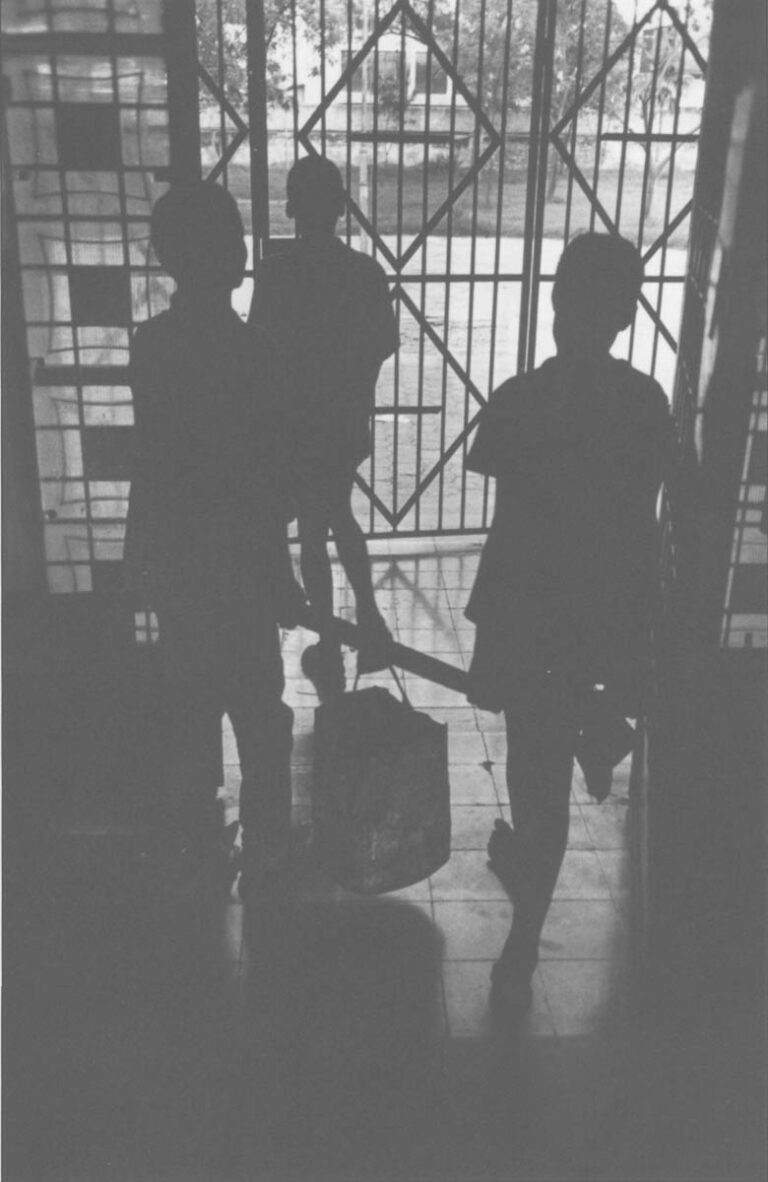

A few days later, on Aug. 17, 1987, in the afternoon, a large group of street kids was taken into police custody in downtown Port-au-Prince, rounded up for no apparent reason and beaten with belts or batons when they tried to run away. Renan Pierre had to go to the police and pay between $6 and $20 for each of the boys to gain their release. according to newspaper reports.

In an editorial, Haiti Progres, a Haitian newspaper, stated:

"It isn’t pure coincidence that the street kids are arrested at the same time that the provisional government attacked and attempted to murder Father Aristide out in the countryside. Devoted to these street boys, he is trying to raise their social status and to integrate them into society. The police and the army have tried to torture these children when they failed to reach their murderous goals with the priest."

An obvious answer to the problem is orphanages. The Haitian Ministry of Social Affairs has approved about 60 orphanages and five adoption agencies but unofficially, the ministry admits, to the existence of hundreds more, run by private individuals or church organizations as well as the state. Many are operated by well-meaning people but many more are not. They dot the capital.

In the fancy suburb of Petionville, charming babies sit in chairs against walls, all scrubbed, ages one to four years. The older ones sing and dance for visitors and kiss the younger children in gestures they have been taught by the teachers or nurses who are their guardians. “Many of our children go to France,” one nurse volunteered, “but we aren’t sure what happens after that.” If you have the time. patience and money. you can find yourself a healthy adjusted baby here.

In another orphanage near the national cemetery downtown. there are no charming babies; no babies at all, but older children who sleep on dirty mats. On a recent visit, the whole house smelled of urine and there was only one man to watch over the children. This male guardian refused to give his name and threatened visitors with charges of trespassing. This orphanage is one of the unofficial ones, operating outside government sanction. Many of these unofficial orphanages, are supported by donations of well-meaning churchgoers in the United States.

When the street boys are picked up by the police, they are taken to the Centre d’Acceuil. a state reform school for boys in the southern slum suburb of Carrefour. It is an imposing building, huge, old, dilapidated, with a guarded front gate. Its young inhabitants range in number from 350 to 400 boys. The government provides a monthly budget for the Centre of $4,000–just about $10 a month per boy. to pay for food, clothes, medicine, education. The street boys hate it and escape as often as possible. However, some choose to stay “for vacation” for a few weeks, especially during political turmoil.

The boys’ tales of incarceration are colorful details of misadventures, but are hard to verify. If a street kid disappears for a few days, the safe bet is that he either went home to visit his family or he has been put into Centre d’Acceuil. If the idea for the place was reform, it is also the best place for boys to learn the ways of the streets.

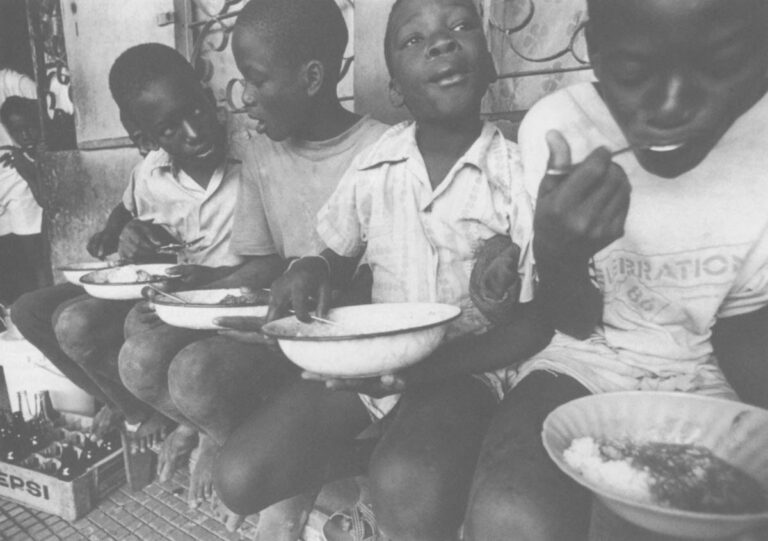

At a Baptist mission school on Delmas Road near Father Aristide’s church, street kids gather outside at noontime for a free lunch. The food is provided by the mission, which is supported by Baptist churches in the United States. The boys and girls are let into a foyer where they are made to sit still by stern matrons armed with hard rubber batons. Their presence quiets the wildness of the children, but two small boys continue to wrestle over a place in line. After a bell rings, the children file into a large dining hall which is filled with rough wooden tables and benches. At each place, there is a plate of food waiting: Rice and beans, the semblance of something meaty, and a glass of milk.

The children are seated. Some dive into the food without hesitation. Others pour the milk into bottles they have pulled from beneath their shirts or dresses and tighten covers onto them. The bottles are returned to their hiding place and then the children eat. The milk will be taken home for younger children or will be sold to someone for cash. All the while, the stern matrons swat the ends of each table methodically. This is to keep the children “in line” although the only sound in the hall is the click of spoons against tin bowls. For the children it is a frightening and humiliating experience. The women are there because they have no choice. One referred to the children as “wild animals who will slit our throats in the night.” But the operation does feed nearly 100 street kids four times a week.

Some of the boys from Portaille Leogane began sleeping in the slum of Cinquieme Avenue, where Johnny Clegy’s mother has a small shanty, after the police arrested and beat some of them during recent political turmoil. The boys sleep on the floor of the shack, all entwined like kittens, and Madame Clegy sleeps on the only bed. The boys wake up early and groom outside with water from a nearby well. A visitor comes by the house to see Madame Clegy. Lesly, one of the street boys. stands behind Madame Clegy as the two adults talk. He pretends to drink from a bottle as he weaves around like a drunk behind the women’s backs.

Madame Clegy is a thin woman, worn and with the same big eyes that her son, Johnny, inherited. She is a sick woman. She has back problems. She is too thin. Lesly obviously thinks she is an alcoholic and he plays the cruel jokes of children on her behind her back. Her tiny son is her only salvation–with the money he earns begging or washing cars. But she repeatedly begs visitors to take him with them, to send him to school, to save him.

There is no breakfast so the boys finally work their way down the hill after causing a little havoc in the market along the way by stealing a piece of fruit. They reach their life-giving traffic light where other members of their loose-knit group have already gathered. Among them is King Kong. He wears a new pair of trousers and the other boys admire them and ask where he got them. From a tourist, he says, and he pulls a broken pair of dark glasses from one pocket and dons them. He seems to have a little money today.

While the other boys wait at the intersection to make money, King Kong wanders off to another corner in the downtown area where men are gambling with the throw of the dice. He tries his luck but after losing on three throws, he wanders on until the late afternoon brings rush hour and another chance to earn money.

King Kong is an angry child. His father beat him. He rarely speaks and the other boys think he is sullen and bossy, hence his name. He seems disappointed and often sits alone at night at the intersection, staring off down Dessallines into headlights of oncoming traffic. Only after weeks of attention will he sing a song for a friend. He is reaching puberty but one suspects that he has known about sex for some time. What does he think about when he sits alone, staring into night? Women, money, gambling, his family, soccer, where he will sleep, the future?

In the former voodoo temple at the other end of the long street, twenty boys are gathered into a dark corner around three candles. The electricity–two bare bulbs–has been cut off because the bill was not paid. The boys must pay a neighbor $3 a month for electricity that the neighbor steals from a main electrical wire running through Tokio slum. This theft is an old Haitian tradition referred to as a “cumberland.” In the center of the group, Wildek Filibert holds everyone’s attention with his tale of the day’s adventure–a visit to the city morgue at the university hospital. This reporter had watched Wildek and now listened to him relate his experience.

Wildek’s Tale

Upon reaching the hospital, Wildek had followed signs written in Creole (Haiti’s main language) toward the “mog” until he spied the entryway. It was at the very back of the grounds. A hearse was parked in front of the concrete slab that served as a staging area for corpses and coffins. He approached cautiously, fascinated and frightened. From behind a second parked hearse, Wildek watched as a corpse was wheeled out of the dark hallway of the morgue on a wagon. It stopped next to a coffin, which was open and on the ground. Two men picked the body up and placed it gently into the coffin. But the arms stuck over the edge and the men had to coax them into a bent position so they could close the lid. A crucifix with the body of Christ adorned the casket and one of the men crossed himself after the lid was lowered into position.

The coffin was loaded into the hearse and the long black car pulled out. A lone man stood on the staging platform. He wore a black plastic apron and a black bowler hat, like Baron Samedia, the voodoo spirit of death, or so Wildek thought. The man smoked a cigarette and stared out into the afternoon. Finally, he went back inside and when Wildek heard the door close, he timidly approached the entryway. He jumped up onto the platform where moments before he had seen the corpse, and peered down the hallway.

On one side was a large aluminum door. This must be the door to the refrigerator room where bodies were piled high, according to people on the streets. It was not until he got further down the hallway that he spied a small body laying on a cart. It was a baby girl. She wore a pink dress but no diaper and she looked asleep. It was the closest Wildek had ever been to a dead body except for his own father. It was something he never spoke of but wanted to understand and that is why he went to the morgue. The sight of the baby, so natural but so quiet, frightened him and he ran out and away from the morgue until he reached the hospital gate. From there, he walked the long distance to St. Jean Bosco Church. He was dazed and his eyes remained downcast, never leaving the ground, until he finally reached an isolated wall. He threw himself into its most private corner and cried without shame.

What sad memory had been sparked by the boyhood adventure? The other boys would never know he had cried. Instead, he gave them a version of the story laced with a bravado completely typical of Wildek. The boys loved the story and for a few minutes, they idolized the young adventurer. One boy gave him a marble and another let him wear his wool hat, for which the weather was far too hot.

That night, Wildek cried himself to sleep, his face turned toward the wall and stuffed into the crook of his arm so the others wouldn’t hear.

©1988 Maggie Steber

Maggie Steber, a freelance photo journalist, is examining life in Haiti.