Text and Photos by Maggie Steber

…Then there is the mysterious something foreigners are always being told they can never fathom: "la psychologie Haitienne.". Deep in the psyche of Haiti lies a violence that goes beyond violence. That this is so is demonstrated by nearly five centuries of history dominated at every turn by death and terror. Some have written and analyzed that Haiti is plagued with the unusual extent to which paranoia, well-systematized delusions of persecution and grandeur…seems to afflict peasants and the elite alike…Haiti, in some dream, in some nightmare, is imprisoned in its past.

"WRITTEN IN BLOOD" By Robert D Heinl and Nancy Gordon Heinl, 1978

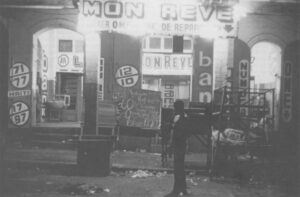

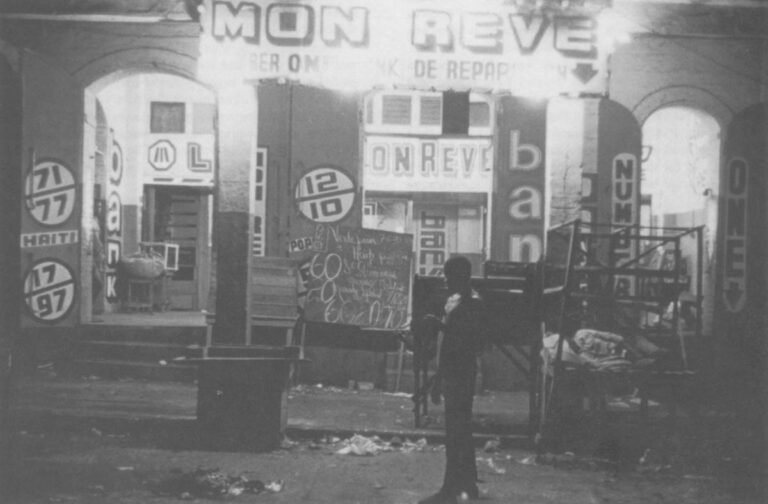

There is a lottery bank on the main downtown street in Port-au-Prince where Haitians will bet their last pennies against the numbers in hopes of winning fortune. It is called, appropriately, Mon Reve or My Dream, because the luckiest numbers come to betting people in dreams. In impoverished Haiti, winning the lottery is one of those communal desires shared by a gambling people. The bank is bustling all day. At night, shadowy figures sit in front of its wide-open doors, silhouetted against the bright lights inside which beckon Haitians in to take another chance at their luck. If the borlette–the bank’s vernacular name–doesn’t draw you in, the games of chance on the sidewalks outside will. A small crowd gathers round to watch some guy who has a winning streak. It is dark on the sidewalk, but light from small lamps attached to the wheels of fortune illuminate the crowd’s faces, which are frozen with intensity.

Gambling is a serious business here. People have put their last dime down on what they thought was a sure bet time after time. But the big win is rare in Haiti and many people have lost all they had.

Just as the dream-come-true windfall rarely comes to the gambling Haitians, so too has elusive liberty escaped their grasp. In a tiny nation where violence and terror rule, a favorite subject of conversation and of dreams–like the numbers–is liberty and democracy. For this, Haitians have gambled the highest stakes. It is the tragedy of this country that so many lives have been lost in so many violent periods, gambled away like chips on a roulette table.

Throughout Haiti, a visitor runs into the dream. It is painted–Mon Reve–across businesses, on the tap-tap buses that carry people to and from work, on slum walls scrawled as poetic one-liners. Haitian painters use the dream of paradise as a theme in the cheap sidewalk art they hope to sell to the few tourists who bravely venture into Haiti these days. Paradise is painted as a dream of jungles and forests filled with all the animals from Noah’s ark, animals that Haitians have never actually seen except in pictures. But they paint them with a trust, in acceptance of a fact that they cannot ever hope to see with their own eyes. A Haitian may not have visited paradise, but knows it exists because he has dreamt of it. Likewise, he may never have known true democracy, but he knows somewhere it exists because he has dreamt of it.

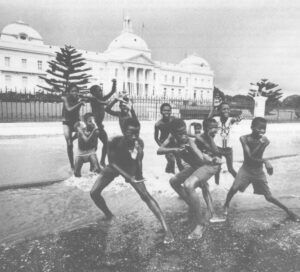

The dream of liberty was borne out of the desperation of African slaves whose miserable lives under the French colonial plantation systems were better spent in revolt than in pain and horror. They dreamt of liberty. In revolt, they won it. Haiti became the first black republic in the world in 1804 and the second independent nation in the Western hemisphere, after the United States. This one brave act of revolt made front page headlines around the world and changed history. When the whip was at their back, the Africans kept the dream of freedom at the front of their minds and communicated it from one plantation to another by way of voodoo drums.

This great thirst for liberty has made Haiti a land of serious dreamers, but traditionally, the dreams have turned into nightmares. Like a plague, nightmares have intruded on Haitians throughout the rule of more than 38 dictators, emperors and presidents. It is the dream-turned-nightmare that brought a dictator like Francois Duvalier to power and which kept his family in rule for thirty years. Each time the Haitians have dared to dream of freedom and gambled on it, the nightmare has intruded.

Liberated Haiti’s first three leaders–Toussaint, Dessalines and Christophe–were men anchored in the modern world. They did not share the freed African slave’s dreams of an African paradise lost. To create a modern black state, they had to be demanding and often cruel. In the attempt to put Haiti on the face of the map of modern times, many former slaves died in the transition.

Years later, when Francois Duvalier, a humble black doctor from the masses ran for president, he was elected on a noiriste platform. In a country run by mulattoes, a man from the black people was immensely popular. What began as a dream when he was elected increasingly became a nightmare when “Papa Doc” Duvalier turned out to be a maniacal leader who used murder and voodoo to maintain a tyrannical rule until his death. He kept his people poor, ignorant and isolated. When his dictator son, Jean-Claude, fled Haiti in February 1986, Haitians once again dreamed of democracy and let a military junta guide them. But the junta overstayed its welcome and turned its head when villains murdered voters at the polls. People who were desperate for change took the chance, gambled, went to vote, and were massacred with machetes and machine guns.

“The dreams Haitians had ten years ago centered around getting rid of Duvalier,” explains Lucien Pardo, a professor who ran for the Haitian Senate in the November 1987 elections.

“People thought when he went into exile, that would clear the path for their dreams. Now, they dream of taking even the smallest steps toward democracy, so treacherous has the path been.”

A Haitian saying sums it up universally: “We chase dreams but we never remember history.”

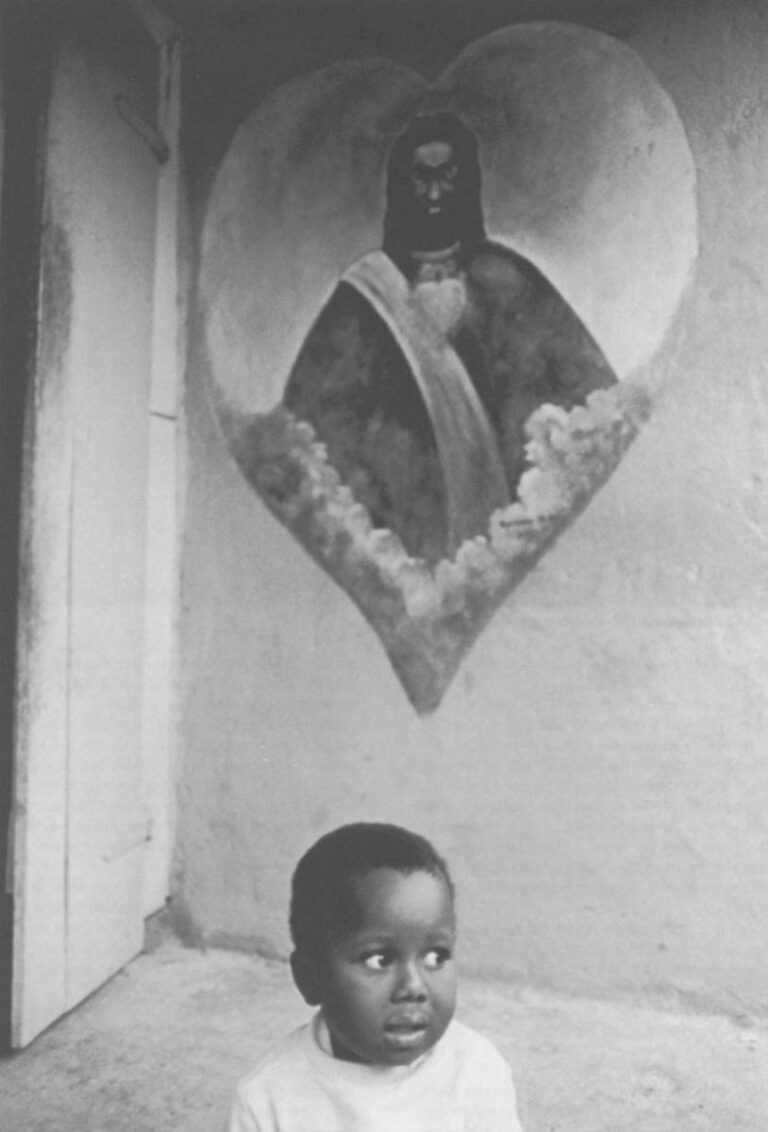

Still, in this land of extraordinary and brave beauty, there are havens for dreams. This is one reason the voodoo religion has maintained its dominant influence over the Haitian culture.

Voodoo is a dreamer’s religion. In fact, one of the most highly regarded spirits in the voodoo pantheon is Erzulie, goddess of love, who is considered to be divinity of the dream. In Erzulie, dreaming picks up where reality ends. She is the attainment of perfection, the realization of the dream. She is the mother of man’s myth of life. Through her, the Haitian is obsessed with the vision of a life that would transcend all the difficulties he must face each day, a dream of luxury.

“Dreams teach us what we know. Dreams of man are carried by the spirits and come from the soul. The spirits are guided by guardian angels.” Andre Pierre chants the words and they pour out of his mouth like poetry. He is an internationally known Haitian painter of voodoo and he is also an houngan or voodoo priest. He is considered by his countrymen to be an authority on voodoo. “The soul lives when one sleeps. The body reposes but the soul walks and talks with its friends.

“The function of dreams, he explains, “is to be the memory of the soul. The function of man is to carry the soul, but the soul has spirit, even when we die. Have confidence in spirits but not in man,” he warns. “That way you will see the truth. All men are one in their dreams. Everyone. Everywhere. All spirits work together to accomplish the mission of God. Each soul has a task to perform, to fulfill a mission for his country. If there is only violence, how can the mission be accomplished? The mission of Haiti? It has none, it has been destroyed since our independence. It is finished.”

In a land of dreams, what do Haitians, want? And why, after so much sacrifice and violence, have they not, as people or as individuals, been able to grasp many of their dreams?

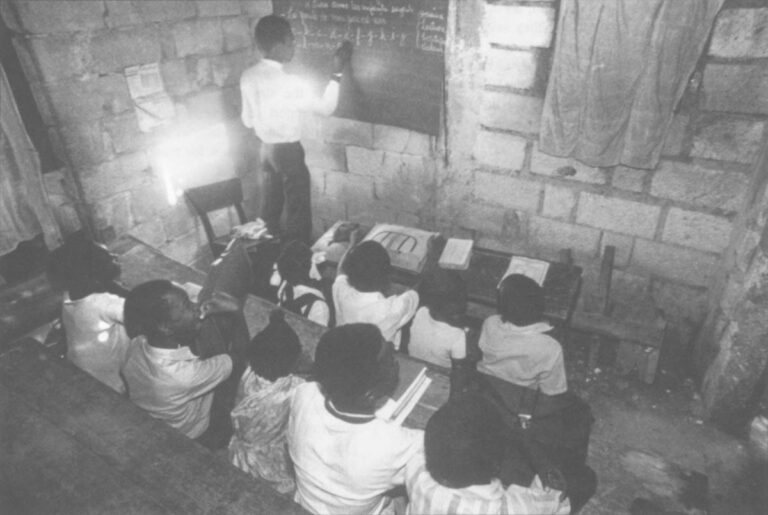

Father Reinald Clarisme, a Catholic priest in the Haitian liberation theology movement, explains that for the majority of people, the “most important dream right now is to have the minimum for living: work, a home, good health, security, liberty in expression, an education that would hold the value of the culture but which would also prepare people for a profession.

“But how do we realize these dreams?” he asks. “To do that, we need a system of government which is disposed to guarantee the human rights that will profit everyone.”

Father Clarisme says that for the elite class, the dream is to leave the country for the United States or Europe to wait out what he calls the battle. “These classes are rich enough to escape the reality of the deviant behavior of other classes. As for the Haitian youth, they are looking. They have ideas but they don’t have the means or the freedom to do it. Whoever wants to help is accused of being leftist or communist so they are afraid to organize.

“In La Saline slum, lives are destroyed. People are abused by drugs. They are poor, abandoned and don’t even have the minimum to carry their dreams. We need to re-educate these people on how to work in a system created by a new government. All this is the responsibility of the state but the state does nothing. Perhaps they don’t share the same dreams as the people.”

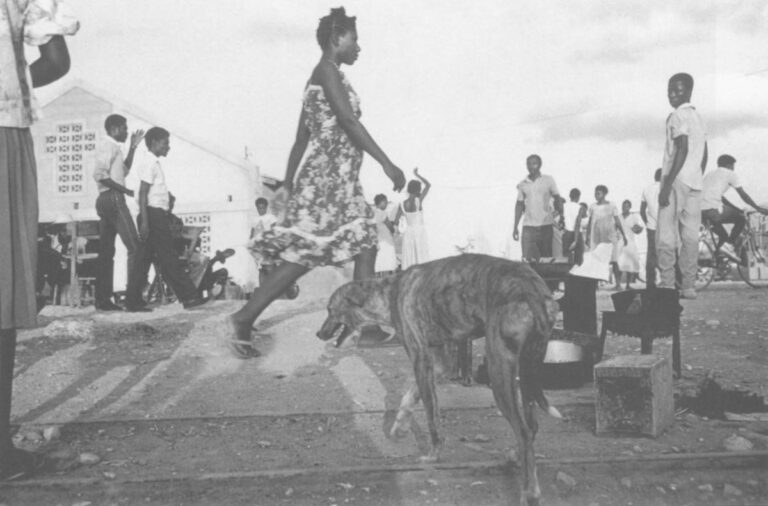

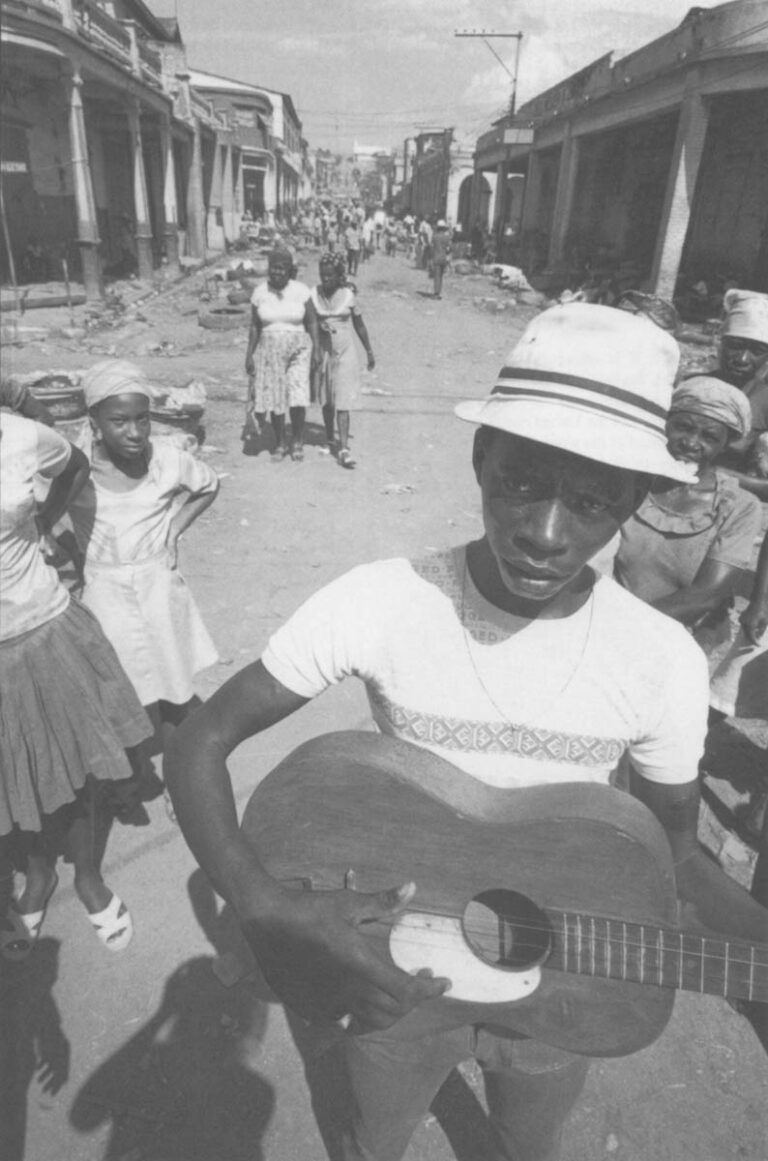

In the muddy slum of Boston, after a midmorning rain, people scurry down one of the main streets of the bidonville. Here and there, women sell small piles of charcoal or oranges or rice, spread out on plastic sheets to protect them from rain and the resulting sludge. Dogs yelp and run from rocks thrown by kids. The whole scene is one of complete frenzy, with a neurotic dailiness to business as usual as the people rush around trying to earn a few pennies.

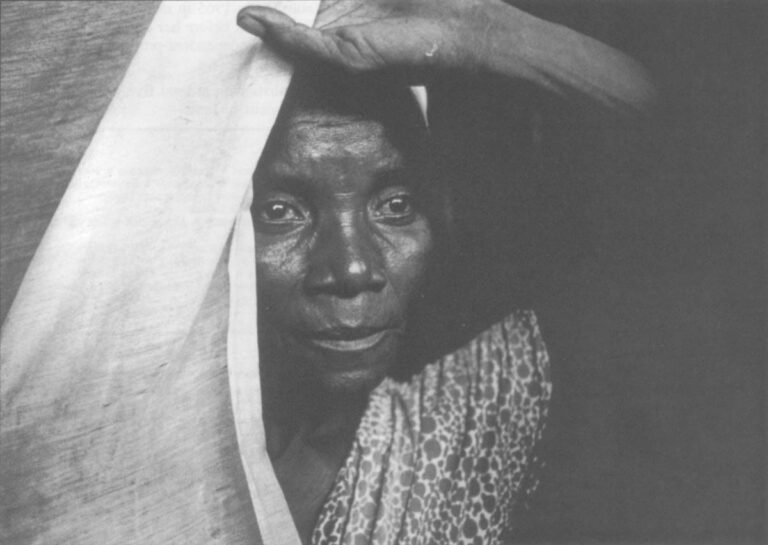

Where Boston slum meets Cite Soleil slum, a woman peers out the cloth-covered door of her shanty. She is unaware of her surroundings, completely lost in her thoughts. When a stranger speaks to her, it takes a few seconds to bring her back to reality. What is she thinking about? She is thinking about a dress she had when she was a little girl. It was bright color with ruffles and it was the only one like it she ever had, she says, because her family was too poor.

No light-skinned woman could ever wear these dresses and look as much like goddesses as Haitian women do. They begin wearing them when they are tiny girls. Even the poorest family will dress their little girls like dolls in these bright fantasies, and pierce their ears with tiny gold earrings and braid their black cotton-candy hair.

Every Haitian woman has worn this dress, even if she grew up to be a glamorous lady of the elite classes who buys her clothes in Paris and New York. And every Haitian woman owns a black dress and hat. During her lifetime, she has many sad occasions to wear these black mourning clothes. Among the poorer classes, it seems as if every woman owns the identical hat which she wears to funerals, weddings and on the plane flight from Haiti to New York when she visits her cousins in Brooklyn.

Across town, in a middle-class neighborhood of Port-au-Prince, three young Haitian women loll on a double bed in the upstairs bedroom of a stately two-story house. They are all close friends and at ease with one another like sisters.

Over the bed, a huge window stands open, allowing a wash of hot afternoon light to fall over the trio as they described their dreams and hopes for Haiti’s future.

“The realization of the country’s dreams are also mine,” the eldest one, 23 years old, said. “We need a change in everything, to make a beautiful house for Haiti, and step by step, we will have it.” She describes the thought as though it floated just in front of her. “Like the so-called revolution against Duvalier, it must he the majority changing things. It is we, the favored classes, who must effect the changes because we are in the position to do that. But we must have changes within the class structure to make things more equitable for everyone in the country.”

The woman whose house it is chimes in. “Yes, I also incorporate my dreams with the real liberation of Haiti. We have to make a revolution a la Haitienne. We don’t need to copy anyone else’s revolution: not the United States nor Cuba nor Nicaragua. People are afraid of the word. They associate it with negative things. They think it means taking freedoms away or taking up arms. But anyone who came here to see for themselves would agree that many things need changing.

“People are already so oppressed by the way they are forced to live–millions in the slums, peasants starving, we, ducking bullets in our houses at night–that it would seem impossible to make it worse. We must take our destiny into our own hands, no outside interference.” With that, she jumps up from the bed and goes to get refreshments for her guests.

Now the third woman, who was dressed in black mourning clothes because of the recent death of her grandmother, nods her head excitedly and claps her hands in affirmation of what her friend said.

“Our revolution will be really beautiful but no one else should be involved. The United States wants to dream for us. Haitians who go to the United States to study and then return to Haiti, come back with an American dream. But this is not our dream.” She sat up. “We want a system of our own for our country, something tailor-made, not something designed by foreign aid. Too many strings attached. Aid is a way of controlling our lives. The white man comes and offers what he has. He can be an aid worker, a minister, a businessman.

“The aid worker comes to kill our Creole pigs, the peasants’ bank, because of swine fever, so we have to buy American pigs that cost more to feed than the peasant’s family. The minister comes and tells the peasant that communism is bad and any thought of organizing is communist and that they should kill the communists, who may happen to be voodoo priests they want to get rid of. Then there are massacres in the countryside.”

The third woman was passionate in relating her convictions. Here was a bearer of the dreams of generations of Haitians, past and future. She paused to look questioningly at the visitor to be sure everything was getting through. “The businessman comes and builds a factory, and pulls the farmer off his land to work there. He now has a boss who controls his fate, and in the meantime, the large landowners just take over the land and own it all, by right or not.

“You can see why we must take our destiny into our own hands,” and she clutches her hands together as if they held the precious dream. “I think in my lifetime, we will have change. We must keep things in historical perspective, but it’s not too far off.”

In Haiti, a proverb claims that beyond the mountains, there are more mountains. It is the peasant farmer’s dream of never-ending land that will yield bounty to its owner. To own all he sees has always been the dream of the Haitian peasant. The African slave won it, and Haitians have been fighting for it ever since. But now the land is dying. Farm plots are small and usually rented, not owned. The land is overworked and the market systems in which the produce is bought and sold are poorly organized. When peasants do try to organize community cooperatives, the large landowners attack them, have them arrested, taxed or murdered. The landowners are suspect and accuse the peasants of being communists. The truth is that once the peasant, who makes up eighty percent of the population, realizes his strength, the landowners are finished.

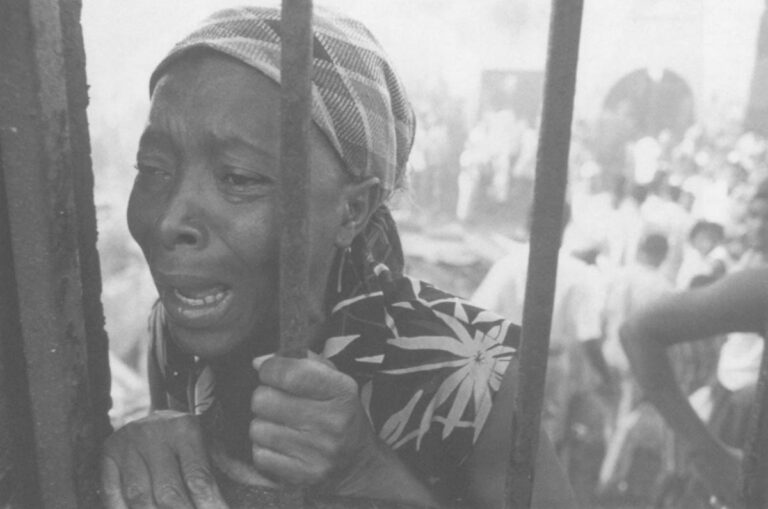

Peasant farmers in Jean-Rabel hoped to organize to prevent large landowners from taking their meager plots. In the summer of 1987, they grouped together and decided to march into town to address the landowners. More than three hundred of them gathered in the countryside. They made signs and sang songs about the land. They left their machetes behind so as not to pose any threat. But the landowners, hearing of their organization, formed their own workers into a force that attacked the peasants as they marched down the hillsides leading into the town. Over three hundred peasants were brutally massacred with machetes, clubs and guns. Their bodies fell into ravines and their blood washed the earth which had been long neglected by rain. Their hope of dialogue was killed along with their dreams. Families were left without fathers and husbands. A widow who described the event and the repression which followed shook her head in dismay as she recalled the tragedy. “The countryside for the Haitian,” she said, “is the cradle and the coffin of all our dreams.”

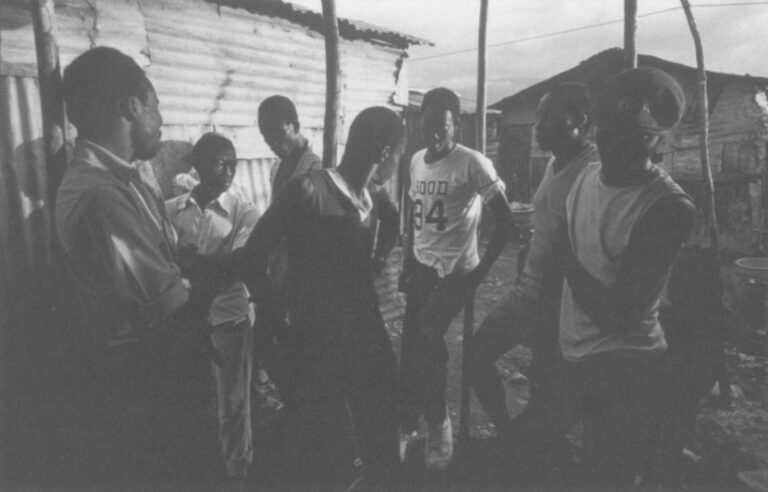

Maurice Milot, known as the madman of La Saline, sits in the same place every day, selling bits of wood. He stares into space and talks to himself. The residents of the slum, the capital’s worst, regard him as both mad and as a wiseman.

“A non-Haitian can never hope to understand what the Haitian dreams are about. Haitians have been shaped by extraordinary circumstances. But in their dreams. they see the reality of how things should have been for them,” Milot explains to a curious visitor.

“Their history has not allowed them otherwise. Understand if you can, that Haiti has been shaped by violence, treachery, a survival of the strongest. It has been kept ignorant and impoverished so that a few could hold onto the power. These few can buy people for a few dollars and make them do anything to each other.”

As he talks, a small crowd gathers and Milot’s eyes glance nervously from side to side, either from caution or from habit. “If you want democracy, you must kill at least half of the people and then start over because greed will never let liberty live here.”

He stops talking to the visitor and begins to ramble so that the crowd finally disperses. As the visitor reluctantly leaves, Milot whispers loudly. “We are our own worst enemy, the enemy lives here among us, we are the enemy,” he hisses, and then he is silent.

©1989 Maggie Steber

Maggie Steber, a freelance photo journalist, is examining life in Haiti after Duvalier.