Salmon culture is a phrase buzzing through the seafood industry, terrifying fishermen, titillating restaurateurs and seducing investors. Raising salmon specifically for harvest may change the way we think about these incredible creatures. The potential is there to produce low-cost, high-protein food. The potential is there but not yet realized. The smart money says it will be.

It was only a matter of time before the salmon’s instinct to return to its natal rivers was exploited. Why not ranch them? people asked. Rear them in a hatchery to smolt size, send them out to graze in the ocean and, when the adult fish come back in three to four years, harvest them. It makes more sense than chasing salmon all over the ocean as commercial fisherman do now.

Or maybe we can farm them, they continued. Raise salmon in net pens in saltwater bays as well as freshwater rivers and lakes until a restaurant or broker puts in an order. Harvest the fish and deliver them to the customer. Salmon on demand. Fresh, the right size and only hours out of the water. Farming Atlantic salmon is a big industry in Norway, Great Britain and even Tasmania, and has been for years. No reason it can’t be done with Pacific salmon.

Simple concepts, yes. Controversial, absolutely. The idea of ranching and farming salmon has exploded in debate.

Environmentalists claim the fish feces and feed debris from salmon farms will pollute the water and accumulate on the ocean’s bottom. Property owners with spectacular water views don’t want net pens right in the way. Commercial fishermen say large scale ranching might very well put them out of business. Sociologists question whether the public domain should be used for private profit. Biologists worry about disease contamination between farmed or ranched salmon and native stocks, and how the infusion of millions of ranched fish will affect the food supply in the ocean and rivers. Some go so far as to suggest interbreeding could mean the end of wild native salmon, currently found in decreasing numbers in the Northwest. Others say salmon culture will be the salvation of the stocks because it will decrease the commercial salmon harvest. Everyone has an opinion. But all agree salmon culture is here to stay.

“It’s not a matter of whether it will go,” said Connie Mahnken, aquaculture specialist with the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS). “It’s a matter of who’s gonna do it.”

And companies in the United States, Canada, Chile, Japan and New Zealand are all trying their hand at it.

It’s February in Southbridge, New Zealand, and the sun is hot. Mitch Cummings shields his eyes as he counts the salmon in the concrete holding pond. Next week they’ll be harvested. The water’s surface is fragmented by a garden sprinkler and tosses back ribbons of sun into his face. The transplanted Oregonian is somewhat embarrassed when asked the purpose of the sprinkler system. “We’re trying to cover all bases,” he said. “We don’t want to be caught by surprise.” The jury-rigged sprinkler is aimed at preventing fish sunburn.

This is the critical year for the New Zealand Salmon Company (NZSC), where Cummings is a hatchery manager. It is the largest of over two dozen New Zealand companies involved in salmon culture. Potential investors in the publicly held company, as well as its competitors, are keeping a close watch on the number of three-year-old adult chinook salmon that return this year. It will be one indicator of the young industry’s future.

No salmon run has been the object of such intense scrutiny since the return of New Zealand’s first Pacific salmon in 1879. Quinnats, as the chinook salmon are known in New Zealand, are just one of hundreds of species of fish, fowl, plants and mammals that European settlers introduced to the “land of the long white cloud.” Settlers formed regional acclimatization societies to speed this process.

Many attempts at introducing salmon failed. In one instance a ship carrying fertilized eggs missed New Zealand entirely. In another, a cage full of smolts, or young salmon, sank to the bottom of Christchurch’s Avon River where the fish reportedly “drowned.” The first quinnat salmon from the Sacramento River watershed in California was released in the Rakaia River near Southbridge in 1876.

The Canterbury Acclimatization Society waited hopefully for three years. Just as the acclimatization attempt was about to be written off as yet another failure, a hunter brought good news. A 15-pound, 21inch quinnat had been caught on the Rakaia. Shot actually. This was not exactly the idyllic, rod-and-reel image the society had envisioned, but the members were ecstatic.

Over a hundred years later and just a few kilometers down the road, attention is once more focused on the returning salmon. This time it’s not the survival of the species with which people are concerned, but the survival of a new industry: salmon ranching.

New Zealand is a nearly perfect location for salmon culture. The water is cool and clean. The introduced quinnats have adapted to pen-rearing and ranching. Labor costs are low. Few people complain about the sight of net pens or ranches because few people live in the country. The seasons are reversed from the Northern Hemisphere so the product doesn’t compete with Alaskan or Northwest salmon in the marketplace. And there is no commercial salmon fishery.

The industry has boomed since the first ranch was formed in 1977. Two years later 100 ranched fish returned to the country. In 1986, over 23,000 were harvested at four recapture sites, or approximately one-fifth the world total of ranched Pacific salmon. Five applications for salmon ranching licenses have been filed since last year. This increase is partially due to the good return of immature quinnats at Tentburn, New Zealand Salmon Company’s hatchery and ocean recapture site.

Tentburn is a $5 million state-of-the-art hatchery located on the plains of Canterbury south of Christchurch. Paddocks of wheat, oats, peas and rapeseed surround the facility. Lambs skitter across the road leading to its 60 concrete rearing ponds, which are capable of holding 160,000 smolts each. In this land of 100 million sheep, one ranched salmon is worth three lambs on the export market.

Salmon ranching is not without risk, however. Something as simple as a mechanical malfunction or as complicated as disease can wipe out an entire year’s production of fish and with it an entire year of income. Most companies have diversified.

The New Zealand Salmon Company is no exception. It produces kiwi fruit and tomato paste and operates a salmon farm on Stewart Island, the southernmost island in New Zealand. Farming has two advantages, according to Rob Lawrence, the salmon manager for NZSC. Salmon reared in net pens can be harvested at any time at any size, thus providing the consumer with fresh fish on demand. The scale of the fish also injects the company with “instant” cash while waiting for the ranched salmon to return.

“It takes a long time to develop ranching,” said Lawrence. “It takes at least two and maybe three cycles (of 3 years each) to get it up and going, whereas with sea cages you just pop ’em in the cage and harvest them as early as a year later.” All but one of the companies ranching also farm. Most of these operations are on Stewart Island.

Today six different companies raise salmon in pens in the island’s Big Glory Bay. When commercial fisherman in the Northern hemisphere hang up their lines and nets in November, the harvest begins at the saltwater pens. The farmers ship fresh fish to ports such as Seattle and Tokyo until March. Most of the 800 metric tons harvested annually ends up on the plates of restaurants at least 17 hours flying time from the island. To those who harvest the salmon, it is a world away.

At five a.m. the men have already assembled on the wharf in Oban. Outlines of the NZSC net pens are barely visible as the boat nears the farm. Four separate farms with 28 or 30 pens each are anchored to the bay’s bottom by a series of two-ton concrete blocks. This morning the water is undisturbed save for the wakes of yellow-eyed penguins and the boat. The vessel pulls aside the first of two pens to be harvested.

Salmon are herded from the eight meter diameter net into a smaller net pen. A blue plastic tarp has been placed under the pen, preventing the circulation of fresh water. Carbon dioxide is pumped into the water to stun the fish.

Within seconds the glass-like pane of water breaks. Silver scales scatter light. Splashing obliterates the sound of the portable radio. Gills working, mouths gasping, the salmon leap and dive.

For five minutes the splashing continues unabated. And then the activity in the water slows. Salmon float belly up, their tails occasionally powering a last futile attempt to escape. Torn Learmonth nods. “Let’s go,” the harvest manager for NZSC says.

The beauty of salmon farming is the efficiency of harvest. Two and a half tons are taken from the pen in less than two hours. Three hours after the salmon have been killed they are on a plane bound for the United States. Thirty-six hours later the filets are an entree on a menu.

Despite the jet-age efficiency, there are problems that may eventually sabotage the industry.

Many observers suggest that New Zealand people, nick named “Kiwis,” readily accept risky ventures. “The ‘kiwi into the wind’ trait runs deep here,” said Lawrence. “Unregulated development, a carteblanche approach, could have a negative effect. We just don’t know.” The number of salmon the waters of the continental shelf can feed is unknown, he added.

But this isn’t perceived as a problem at this time, Lawrence said. However, he added. if many more large hatcheries were established that pumped out millions of smolts each year, that could change.

The accidental catch, or by-catch, of salmon by commercial fishermen is another problem. Cod and barracuda fishermen cannot legally fish for salmon. However, their by-catch is at least 100 metric tons, an eighth of what the salmon culture industry harvests each year.

Mitch Cummings, hatchery supervisor, is philosophical about the situation. “Maybe the by-catch is the price you pay for grazing in the public domain,” he said. Cummings discounts arguments that a private profit shouldn’t be made on a public property. He suggests that the large hatchery systems that most states and countries depend upon to provide fish for their commercial and sport fisheries are no different from ranching. “The Japanese and the Alaskans are basically doing ranching,” he said. “They harvest in the bays, but there’s no reason they couldn’t harvest right on the site.”

Japan is three thousand miles and a culture away from New Zealand. The first thing a visitor notices is the quiet. Cricket songs rise above the sound of 5,000 feet strolling toward Tokyo’s Meiji Shrine. The springs of a scale whisper as a worker carefully weighs salmon roe in a Hokkaido processing plant. American tourists with their noisy ways are politely tolerated in the soba-ya (noodle-shop) by other diners.

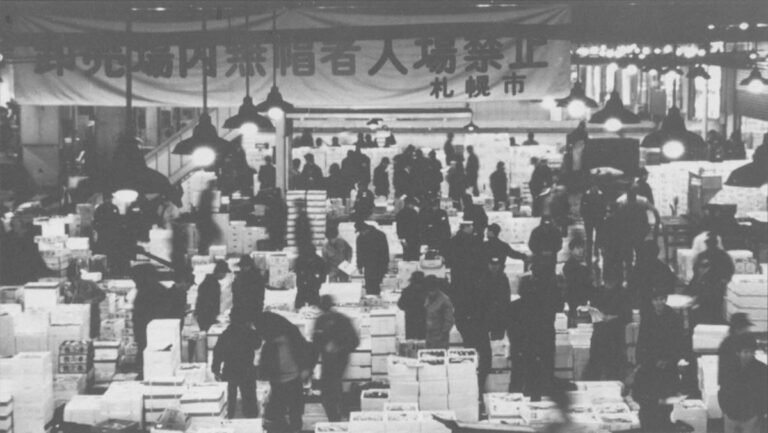

So it is a shock to wander into the fish market of Tsukiji at five a.m. and discover silence sleeps elsewhere.

Horns blare. Engines roar. Styrofoam squeaks. Voices shout. Look alive, step quickly, or run the risk of becoming a spot on the spotless floor.

Stacked on tables and stacked on floors are thousands of species of sealife: blue fin tuna the size of Honda Civics; crates of live crab in sawdust. Fish in boxes, fish in crates, fish in aquariums and salt-water tanks and freshwater buckets. When was the last time you saw live fish in a fish market in the United States?

Another auction begins. The laughter and the joking and the movement and the discussion all end as rows of men, numbers in hats, clipboards in hands, turn their attention to the auctioneer. He blasts out the prices and lot numbers, commanding the men to bid. Fingers pierce the air as brokers reply. No stopping, no slowing, the group moves from row to row of salmon or tuna or roe or squid until the section is done. Then the buyers disappear.

It is here that a person begins to get a sense of the importance of seafood to the Japanese. The Japanese have the highest consumption of fish in the world: 75 pounds per person per year. They raise shellfish and seaweed, octopus, eels, sea urchin and salmon and are known as the foremost aquaculturists in the world. But it isn’t until you see the acres of sample fish spread out in one spot that you begin to understand why the Japanese own 80 percent of the salmon processing plants in North America. Why they are involved in aquaculture in Chile, Canada and New Zealand. Or why some individuals risk going to jail and paying a fine for illegally importing Asian salmon laundered through the United States.

From the sashimi bars at Tsukiji to Aihara’s Restaurant in Ishkara, salmon is an honored guest. Twenty years ago that salmon might not have been a guest at all. But Japan’s production of chum salmon has increased ten-fold since 1965.

In 1955, the government began a series of five-year plans designed to increase domestic salmon production and reduce dependency on off-shore fishing. When the United States and Soviet Union extended their coastal zones in the 1970’s limiting that fishing even more, the Japanese were ready.

“We anticipated the expansion of the zones,” said Takeshi Yamamoto, a government fisheries official. “So we expanded our production.” The country’s domestic chum stocks now represent 38 percent of the world’s production of Pacific salmon.

Forty-nine million chum salmon return to Japan’s northern coast each year, an area about one-third the size of California. Over 168,000 metric tons of fish are harvested. All of the 2 billion smolts released annually are raised in hatcheries. The statistics are staggering. The U.S., in comparison, released approximately 805 million smelts in 1986.

“Salmon culture has developed like a flower taking a hundred years to blossom,” said one government official. The technology is certainly not new: the Chinese propagated fish as early as 2000 BC and probably passed their knowledge to the Japanese. In 1716, samurai Buheiji Aoto divided a river into several channels to increase its spawning area and in 1888 the first hatchery was built on northern island of Hokkaido. Salmon are now produced in 16 northern prefectures or states, and Hokkaido by 313 private, prefectural and federal hatcheries.

The goal of the modern hatcheries is no longer to just supplement the number of fish in a run. It is to create and maintain those runs. After pollution and over-fishing destroyed most of the native salmon, Japan imported millions of eggs from North America to rebuild its stocks. Soon the hatcheries’ production eclipsed the production of the short coastal rivers. Fishermen happily filled their holds with more fish. They became dependent on the increased harvest and the Japanese were locked into an extensive hatchery system.

“If we stopped artificial propagation, fishermen wouldn’t be able to catch any salmon,” said Chikara Iioka, a spokesman for the Iwate Prefecture.

Unlike the Northwest and Canada, where sport, commercial and Indian fisherman all use the resource, salmon in Japan have only one purpose.

“The role of salmon is for the commercial fishermen,” said another fisheries official. The fishermen are protected by laws nearly a century old and have exclusive rights to the salmon.

Those rights have been controlled by various forms of government for centuries. In 1948, new regulations voided the old arrangements and replaced them with fisheries cooperatives.

The government subsidizes the co-ops. For example, the Iwate prefecture reimburses the co-ops 75 percent of the construction cost of new production facilities. In addition, it buys the smolts produced for approximately half a cent each up to a total of 300,000 fish. Since the government then owns the fish, it is illegal to capture them without authorization. Once a year the public has the government’s permission. For a little more than six dollars, a person can wade into an Iwate river and catch a salmon bare-handed. Only one chum per person, please.

Much more efficient than hands are the sea co-ops’ huge setnet traps. They are over 900 meters long and 60 meters wide. Fish swim through three chambers with one way entrances and become trapped in the third. The average harvest is 6000 fish per setnet. The record is 20,000.

Some of the salmon harvested by the fishermen will be sold to local merchants or shipped to larger markets like Tsukiji. The rest will be sent to processing plants.

Just one building away from the Miyako market is a rew processing factory run by the Federation of Miyako Area Coops. Almost everything is done by hand-from stripping the eggs to sorting them into different grades and sizes, from washing the roe to loading it into the large tanks of brine water.

The product, salmon roe, is eaten raw as well as cooked. It is used in everything from sashimi to Ishikari-nabe, a soup made of salmon and tofu. The Japanese have an appreciation of the delicate flavors of roe as well as the culinary appeal of each of the six species of Pacific salmon. “Our palate is very varied,” said Masaaki Sato of Zengyoren, a federation of fishery cooperatives. “The taste buds of our tongue have an increased sense.” It is because of this that the government is turning its attention to a second goal.

“We are changing our target from increasing the amount to improving quality,” said Takeshi Yamamoto of the Japanese Fisheries Agency. There are two ways to create higher grade fish, he continued. One is to emphasize hatchery programs featuring different species such as sockeye, coho or cherry salmon. The other is increasing the oil content of the flesh, making it more succulent. The government is attempting to reach that goal through egg transfers from one river to another and through genetic manipulation.

Many are concerned that the gene pool’s diversity is shrinking due to these egg transfers and the years of interbreeding. Negative characteristics that tend to be weeded out by nature may surface because of these practices, experts warn. These traits include a sensitivity to disease or a tendency toward smaller fish.

To prevent this problem, Hokkaido’s fisheries agency wants to set aside four island rivers which would act as gene banks. Stock in these streams would not be mixed with salmon from other waterways, thus keeping its gene pool unadulterated.

Officials admit that the installation of the “gene bank” plan is many years away. First streams must be found where the stock is relatively pure. After a hundred years of aquaculture that may be easier said than done. And, once those streams have been chosen, the commercial fishermen must agree to the plan. The architects of the plan anticipate a three-to-four-year fight as the co-ops and government negotiate the necessary restrictions. Salmon culture is at best a precarious compromise.

Masakazu Yoshizaki doesn’t think the resource should be compromised. The anthropology professor of Hokkaido University was one of the founders of Sapporo’s Come Back Salmon Society, and is now its president. He is worried about the long-term effects of genetic inbreeding and concerned that one of nature’s miracles has been turned into an efficient production machine. Salmon should be enjoyed naturally, according to Yoshizaki, as the resource was 30 to 50 years ago.

“Then the Japanese people lived with the environment,” he said. “Now they don’t.”

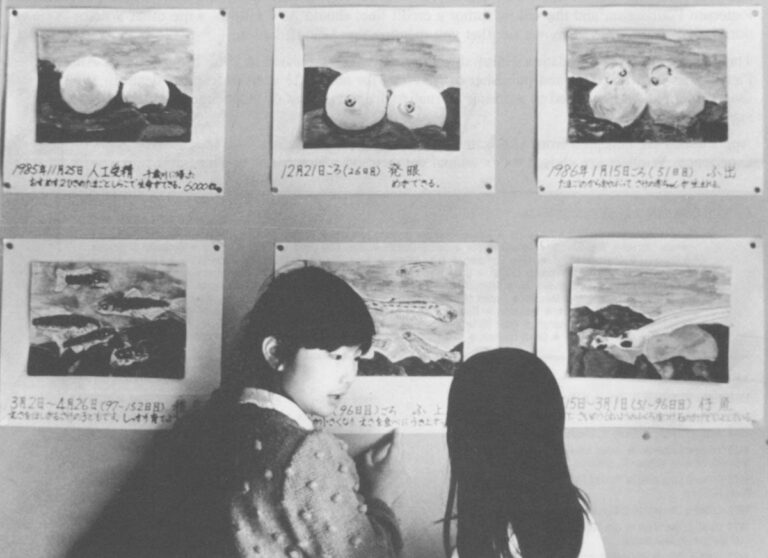

Come Back Salmon Society (CBSS) was formed to pressure the government into cleaning up Sapporo’s Toyohiro River. Once that started the CBSS began raising money for a museum. The Living Museum of the Salmon, finished in 1984, is likely the only facility in the world devoted entirely to salmon. It was founded to teach children about the resource and its importance within nature’s framework.

A hands-on hatchery releases over 300,000 salmon each year. Magnifying glasses highlight the intricate beauty of chum eggs hatching. Down the hall, all six species of salmon swim through aquariums. Thousands of schoolchildren tour the facility each year.

Through the years a partnership has evolved which unites the schools of Sapporo with those of North Vancouver, British Columbia. Last March, Japanese children visited Canada to study British Columbia’s salmon. These children from two countries, who couldn’t even understand the others’ language, had been brought together by their respect for the resource.

The future of Pacific salmon lies in the hands of many cultures: the Ainu and Yakima Indians, the Russians, the Americans, the Japanese and Canadians, the Kiwis and the Chileans. But no matter what policies these people adopt, one thing is certain, say most observers. The future will include salmon culture. It has to in order to provide enough fish for commercial and sport fishing.

All countries supplement their wild salmon runs with hatchery-produced fish. The United States releases approximately 805 million smolts annually. Japan pumps over 2 billion into the ocean each year, with Russia close behind. Canada’s hatchery system produces about 500 million a year. Even the Chinese are enhancing their stocks. The question that must be answered is how do these releases and the private salmon-ranch releases affect the well-being of wild stocks?

Few question the hypothesis that accidental interbreeding between native and farmed or ranched stock will weaken if not devastate the genetically unique wild salmon. What is not known is the impact that large numbers of hatchery-produced salmon may have on the amount of feed in the ocean, rivers and streams.

Scientists believe the ocean and watersheds have a finite amount of food. While the number of salmon now produced doesn’t begin to come close to historic levels, some ocean and river feeding areas may be “overgrazed.” In the food fight between wild salmon and artificially propagated fish the latter will win, experts say. Hatchery-produced fish, raised in high density situations, spend their entire lives competing for food.

Biological concerns are not the only salmon-culture questions with which to wrestle. Who owns the privately ranched fish while they are at sea? Once in the ocean the fish become a public commodity, according to legal precedent. While salmon ranchers accept the concept, they claim that commercial fishermen prey upon the returning ranched salmon. This is unfair, say the ranchers, because the fishermen know when and where the fish are returning.

The fishermen respond that the salmon ranchers are making private profit from a public resource and ask if this is just.

Critics ask commercial fishermen if they, too, are not making a private profit from a public resource. Half of the salmon produced in Washington state are hatchery fish. General fund tax money supports these hatcheries. Therefore, the public subsidizes the fishermen.

Certainly these questions must be addressed before salmon culture can come into its own. But the day may come when all the salmon we eat is raised in a pen or harvested by ranchers. This thought is disturbing to many.

Pacific salmon mean much more to the people of Northwest than a great-tasting source of protein with low cholesterol. Salmon represent the underdog, always struggling and sometimes winning against great odds. They are a reminder that nature has a plan for all creatures, that the environment is indeed a series of interlocking spheres. The salmon symbolize an innocence lost when the vast forests were cut and the raging rivers dammed and when the views of the mountains were replaced by city skylines. And maybe a bit more of that innocence will be destroyed when salmon are raised like chickens.

“The lack of pure nature destroys the human mind,” said anthropologist Masakazu Yoshizaki. And pure nature is the essence of the Pacific salmon.

Salmon culture and you

Just where did that alder-smoked salmon filet with a hint of rosemary come from? Was it pulled from the sea by exhausted fisherman in the middle of the night in the middle of a storm? Or was it taken from a netpen in the early hours yesterday specifically for the restaurant in which you are dining? There’s a one in ten chance that the fish was from the latter. And, three years from now, those odds will likely triple. The gold rush is on. If you’ve ever had any interest in salmon culture, you better get your Atkins incubator tuned up and start making salmon babies. Some experts feel you may already be too late.

United States

Three main problems face salmon culturists in the lower forty-eight: the resistance of waterfront property owners, nicknamed NIMBY’s for “not in my backyard,” to farms and ranches which impede their views; water quality and bottom debris from farms; and the political clout of commercial fishermen.

California has one experimental ranch, Oregon has 12 ranches but no farms, Washington has no ranches but three companies with seven farms and Alaska has 15 private, nonprofit hatcheries which for all intents and purposes are ranches.

Canada

Salmon farming has exploded in the last two years on the largely uninhabited Sunshine Coast of British Columbia. When asked how many net-pens were operating in the province, Bud Graham of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans replied, “Which day of the week do you want? The number is growing exponentially.” As of’ March 19, 1987, a hundred farms were operating with 466 applications in the permit process. A year before, there were only 30.

Japan

Japan is the largest producer of farmed Pacific salmon. The country supplies 2,500 metric tons of the world total of 10,000 metric tons, the vast majority from Shizugawa-city.

Pollution from the last decade of farming may throw a wrench in the works. Tests indicate sediment build-up of 15 to 30 centimeters on the bottom of the 14- to 22-meter-deep bay.

The fishermen are trying to find an answer to the problem. They are considering solutions as simple as “crop” rotation to one as complex as coating the bottom with a charcoal based material. No one knows if either will work.

Norway

The giant of salmon culture, Norway raises only Atlantic salmon. The country’s production of’ salmon has been estimated at 43,000 metric tons per year. Three years from now it will be well over 90,000 metric tons. For perspective, the world’s natural production of wild coho and chinook is between 45,000 and 60,000 metric tons per year. Norway’s companies are investing in Canada, the U.S., Chile and Tasmania.

Chile

A half dozen companies from four different countries are producing coho, chum, chinook and Atlantic salmon. Jon Linbergh. a salmon culture consultant, is convinced Chile will be second only to Norway in tonnage of farmed and ranched fish in a decade.

Like salmon culture everywhere, the endeavors have not been without trials and tribulations. Only five chum out of thousands released returned in one experiment with ranching. That was bad enough, but to add insult to injury, the salmon returned 500 miles south of where they were supposed to.

©1987 Natalie Fobes

Natalie Fobes, photographer on leave from the Seattle Times, concludes her chronicle of the Pacific Salmon and their struggle to survive.