SEATTLE–It was a disaster. The banks of Seattle’s Duwamish River were covered with carcasses of adult salmon returning to spawn. Jaws open, eyes intact, thousands of dead fish had been in the mud for twenty hours undisturbed by the myriad of birds which, under normal circumstances, should have devoured much of the flesh during that time. This was the first clue that toxic chemicals were involved.

The second came from eyewitnesses of the Saturday afternoon kill last September. Fishermen hip deep in the river’s tidal currents watched, bewildered, as fish burst from the water and beached themselves on the bank. A toxic reaction, said biologists.

Not knowing how to report the frenetic activity, sportsmen called 911, the county-wide emergency number, and the State Patrol. No one, neither private citizen nor state employee, called the Department of Ecology’s (DOE) toxic spill hotline.

Thirteen hours later, DOE personnel began their investigation. Evidence needed to ascertain the source of the spill had disappeared during those intervening hours. Whatever toxin might have been in the water had since been flushed downriver and diluted by the tidal action of Puget Sound. The salmon had been dead too long for an accurate chemical analysis of their tissues. The only indicators left were the eyewitness reports of crazy activity, a mucus substance found in the gills suggesting contact with a foreign substance, the start of the kill 50 yards below a sewage treatment plant’s outfall, and the uneaten eyes.

Months after the kill, little more has been learned. Officials know that a deadly chemical such as chlorine or ammonia, both by-products of sewage, was in the river below the sewage treatment plant outfall and for five miles downstream. They know the fish in that stretch were hit with this wall of poison within a relatively short time. They know the toxic emergency response system failed and they know that at least 2,225 salmon died. What they don’t know, and what they will never know, is why.

This is not the first nor will it be the last fish kill in Washington. In the past decade, 113 kills have been caused by a variety of reasons. In one case, manure spilled out of a containment pond and poisoned a salmon-producing creek. In another, the water level of the Columbia River was lowered during an experiment leaving 1.6 million wild chinook fry high and dry.

As tragic as these kills are, experts say they should not be the main source of concern. The cumulative effects of habitat destruction pose greater threats to the health of Washington’s Pacific salmon than any one-time loss of fish. “It’s an insidious problem,” said Yakima Indian Nation biologist Larry Wasserman, “the slow degradation of the resource over time.”

It will take time and billions of dollars to repair the damage. “Putting these systems back together will take as long as it took to tear them apart,” said Terry Williams, head of the Tulalip Indian tribe’s fisheries department.

During the last century the salmon’s habitat–cool, unpolluted, gravel-bottomed streams–has been haphazardly destroyed with little thought of long term consequences.

Hydro-electric dams block miles of spawning ground. Silt and woody residue from improperly logged mountainsides choke streams. Irrigation needs drain rivers, eventually returning the water heated and laced with chemical residue. Widespread development causes rapid run off, toxic contamination as well as changes in the course of some waterways.

Environmentalists, conservationists and biologists have warned of the incremental effects of uncontrolled abuse since the late 1800’s. Only recently have their cries been heeded. Gigantic breakthroughs have resulted.

In 1980, a federal court judge ruled that the Northwest’s dam-regulated rivers must maintain water levels in which salmon can maneuver. Some rivers had been drained for irrigation and power production leaving the migrating salmon stranded.

The United States-Canada Pacific Salmon Treaty, signed in 1985 after 20 years of negotiation, divided the amount of ocean-traveling salmon between the two countries’ commercial and sport fishermen. Just as importantly, the treaty emphasized an aggressive environmental improvement program.

The Timber, Fish and Wildlife proposal in Washington state, agreed upon late last year, stressed that all timber harvest plans for private and state land include consideration for water quality, land stability and the wildlife needs unique for each site.

Wide-ranging efforts certainly, but is it too late? Is the salmon’s habitat irrevocably destroyed? And do these solutions get to the heart of the problem? The people problem?

“The biggest problem that faces the fish is people,” said Bill Wilkerson, former director of the Washington Department of Fisheries. “And the way man treats the environment in which fish must live.”

The settlement of the Northwest was based on the belief that the resources were infinite. Who would doubt the validity of that tenet when viewing ridge after ridge of Douglas fir, Western hemlock, Sitka spruce and cedar, or watching millions of chinook salmon leaping over Celilo Falls on the Columbia River.

Those days of infinite resources are gone. The only thing that seems to have remained the same is the attitude of the people.

“They still think this is the wild west where you’ve got another forty acres over the horizon that no one has ever seen and no one has ever touched,” said David Ortman of the environmental group Friends of the Earth.

Examples of what shouldn’t be done to the environment abound from the Columbia River’s source eighty miles north of the United States border to its mouth over 1,250 miles away. The river is old, created at least 15 million and probably closer to 100 million years ago. The Columbia and its main tributaries, the Snake and Yakima rivers, drain an area of 260,000 square miles in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Utah, Wyoming, British Columbia and Alberta.

The 2,700 foot elevation drop from headwaters to mouth makes the river ideal for production of hydroelectric power. Forging through high plains, deserts and forests, the waterway before development was a rapid, raging system blasting into the Pacific Ocean at a rate of more than two million gallons of water a second.

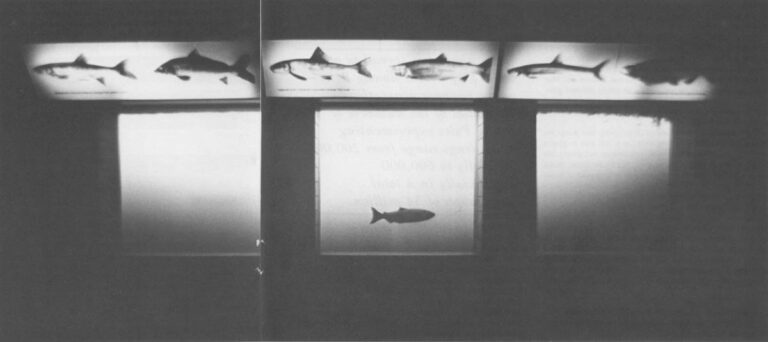

Home to the chinook, sockeye, chum and coho, the mighty Columbia was also a highway for the salmon who spawned as far as 1,200 miles from its mouth.

Today the river is a series of flaccid lakes formed by 13 major dams, monuments to the area’s desire for power, barge navigation and irrigation. Ironically, the Columbia’s only natural “reach” is located within the Hanford Nuclear Reservation, one of three proposed sites for a national, high-level nuclear waste repository.

Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal offered a proposition which the people of the Northwest found hard to refuse. Utilize the river as a massive source of hydro-electric power, he suggested. It would guarantee “cheap manufacturing, production, economy and comfort on the farm and in the household.” Public Works Administration employees began construction in 1933 of the largest hydro-electric and irrigation dam in the world at Grand Coulee, Wash. The 343-foot-high giant supplies water to irrigate half a million acres and can produce 6,464 megawatts of electricity annually, enough to keep Seattle glowing for six years.

Grand Coulee dam cut off more than a thousand miles of spawning ground. The Indians sadly noted that the famed spring hogs–50 pound chinooks–no longer returned to the river. This genetically unique run, produced upstream from the dam, was wiped out. The salmon could not get around Grand Coulee. It had no fish ladders.

Over 130 dams were completed in the basin destroying one third of the 12,000 miles of salmon habitat. The number of fish plummeted. In 1884, fifteen million salmon fought their way through the rapids of the lower river. In 1984, only 2.5 million made the same journey.

Dams are deadly to both returning adults and migrating juvenile salmon, known as fry. The fry may become “lost” in the large reservoirs, crushed by the turbines or, when flushed over the spillway, victims of the fish equivalent of the bends. Birds and fish eat the stunned juvenile salmon. As much as 30 percent of the run dies at each dam.

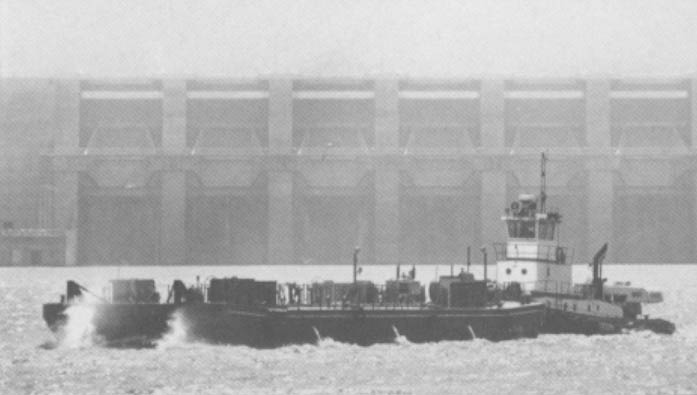

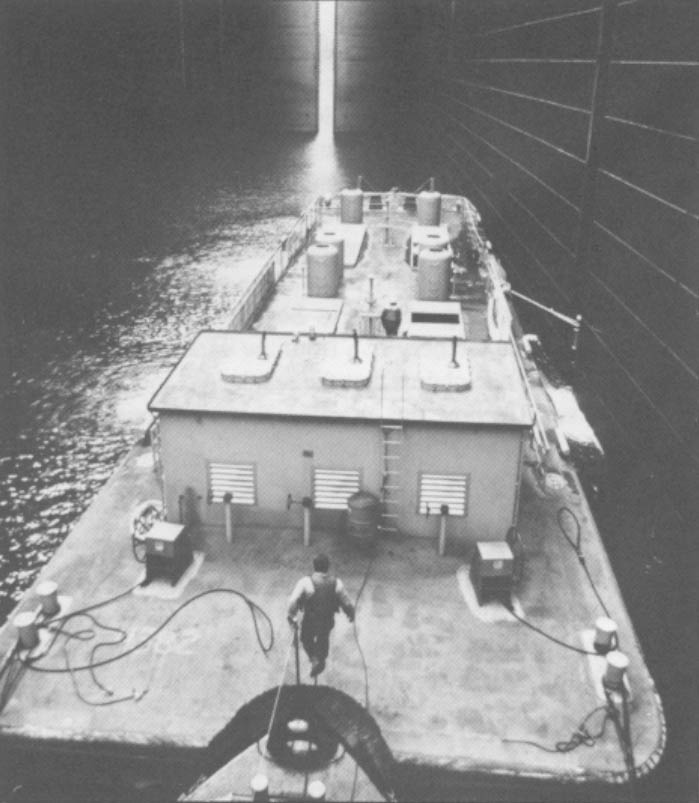

In an effort to increase the survival chances of salmon and steelhead trout, fry are trucked and barged around as many as eight dams. “Operation Fish Run” has been directed by the U.S. Corps of Engineers with assistance from various state and national agencies since 1981.

Fifteen million fry were transported in 1985, cruising 280 miles downriver in one of four Corps barges. The cost of mass transit for fish: $2.5 million to $3 million a year, a price project coordinator Jim Athearn feels is a bargain. “It’s very cost effective,” he said. Without the transport system, water would be diverted from the dams’ power-producing turbines to the spillways. “The spill needed to help the fish over the dams would cost $20 to 30 million in lost power,” he said.

The program has had mixed success. While adult steelhead returns have increased dramatically, chinook returns are greater by only one or two times. Reasons for this poor showing are not known. Some biologists claim the hatcheries are producing inferior fry. Others point to disease and say the practice of transporting thousands of salmon together contaminates the healthy ones. But, Athearn suggests, in a system where every fish counts, one or two times greater return does not seem like such a bad deal.

Twenty local, state, tribal and federal agencies affect Columbia River salmon. These include giants such as the Bonneville Power Administration, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission as well as county public utility districts with small hydro-electric dams. The Bureau of Reclamation channels Columbia River water for irrigation purposes. To date, 7.6 million acres of farmland has “’bloomed in the desert” with an annual increase of 53,000 acres.

Just how important is water to residents of Eastern Washington?

WDF’s Steve Keller discovered two irrigation diversion dams were taking too much water from a salmon-producing stream. Concerned, he decided to talk with the parties involved.

Keller found the owner of the first ranch in his field. After exchanging pleasantries he began to discuss different solutions to the problem.

The sun-etched rancher politely interrupted, looked the biologist up and down and said, “You’re not from around these parts are ya?” He went on not waiting for an answer. “Well, over here, we just might, we just might, let you fool around with our women…but we won’t let you fool around with our water.”

Without the water, the sage-brush flecked hills would not produce the apples, asparagus, onions and wheat which have become synonymous with Washington state. Thousands of farmers would be out of business. But irrigation practices can contribute to the demise of the salmon runs.

Water returned from irrigated fields is warm and may contain pesticides, phosphates, nitrates, sediments, increased salinity and fecal coliform bacteria from animal wastes.

If screens are not placed at outlets of diversion channels salmon become confused and enter the irrigation system. The trapped fish die.

Wasserman is discouraged by the ranchers’ and farmers’ apparent lack of concern for the salmon habitat.

“Creeks are just conduits of water for most people,” he said. “It’s a classic resource battle, and water is more valuable to the valley.”

“The whole habitat business is one of incremental loss,” said Yakima Indian Nation fisheries head Lynn Hatcher. “It’s insidious loss that over time causes the destruction of the runs. If we lose one creek (out of 100), it’s no biggy…two more, not that big a deal. But if we lose 90, that’s 90 percent of the streams. Why there’s a fish left in this basin is beyond me.”

No coordinated set of rules or regulations oversees agricultural techniques in Washington, unlike forest practices. Many problems have resulted. The ground’s ability to absorb and release water evenly has been destroyed by years of overgrazing. Shade-producing vegetation which keeps the streams cool and provides food and shelter for the salmon has been eaten by livestock. Silt from the five to ten tons of topsoil annually lost per acre has choked the waterways. Four hundred tons of silt washes into the Yakima River per day.

Most of Washington’s rivers begin in one of two mountain ranges that traverse the state. The Yakima is no exception.

Born high in the Cascade Mountains, the river takes its time traveling 220 miles to the Columbia. At first glance the area appears untouched, pristine with golden-leafed aspens and cottonwoods bowing over the water. Douglas firs drip lichens from their branches and shelter deep-hued ferns. Upstream, tributary Cabin Creek wanders past an ancient trading trail, still covered with snow late in May. Indians and explorers trod from the high plains of Eastern Washington to the coast using this path.

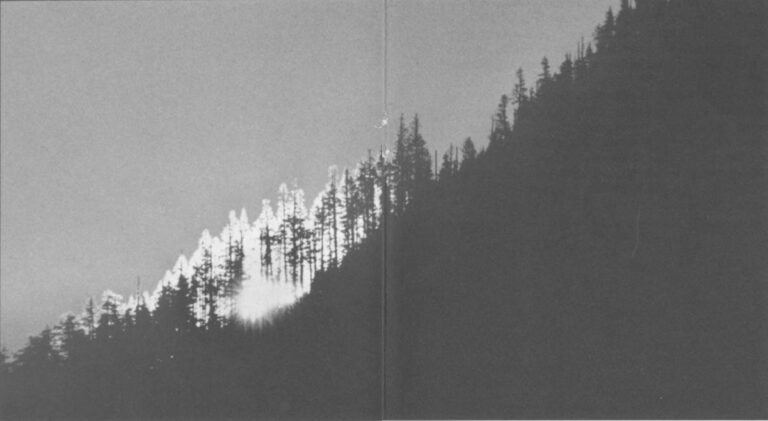

Just over the ridge, the scene changes. Stumps and bare earth greet the horizon. Hundreds of acres of once forested land bear the unmistakable mark of clear-cut. Streambanks are denuded of vegetation, hills are developing landslides, river channels are splintering indicating heavy loads of silt. This is one of the most shocking examples of what is referred to by resource managers as “improper logging techniques.” And it is legal.

The Forest Practices Board, which governs logging on state and private land, devised rules and regulations regarding the harvest of Washington’s 17 million acres of commercial timberland. Those guidelines, now in the process of being updated, had been criticized because there were “loopholes you could drive a loaded logging truck through,” said Terry Williams.

Early last summer, environmentalists, tribal leaders, timber industry representatives and officials from state agencies sat down to revise the Forest Practices rules and regulations. They began with one basic concept. “No two rivers are alike. Even within one river system no tributaries are alike,”’ said Williams. “’A blanket management plan doesn’t work. River systems tend to be dynamic and alive. Regulations are not.”

The coalition agreed on a comprehensive management scheme shortly before Christmas 1986 which, when implemented, will bring rational and realistic management to private and state forests in Washington.

Nicknamed the Timber, Fish and Wildlife proposal, it is unique in many ways. For the first time the timber industry publicly negotiated private land use with non-industry people. For the first time the state and tribes discussed joint management of land. And for the first time the guidelines put forth included language concerning water quality, cumulative land use impacts and wildlife provisions.

The number of trees cut under these new guidelines will be determined in one of two ways. Timber companies can harvest according to a set schedule or go with a “site specific” rate.

If the latter plan is chosen, a team of experts walk the land. This team, consisting of the timber company’s agents, tribal representatives and officials from the state, “devises a prescription to provide environmental protection as well as maximize the timber harvest,” said Wasserman. It doesn’t mean less logging; it doesn’t mean more logging; it means better logging, he said.

The proposal has been accepted by the Forest Practices Board and praised by experts. But the battle hasn’t been won.

A minimum of $6 million will be needed by state agencies and tribes to implement the plan. In a state strapped for money, financing the agreement may be the toughest hurdle of all.

Logging has often been singled out as the destroyer of salmon habitat but experts stress that environmental damage due to urban development is harder to control. “The tribes have always said they’d rather have a timber company for a neighbor than a condo or a developer,” said Williams, noting that ownership by timber companies keeps huge tracts of land out of development.

WDF habitat specialist Steve Keller agrees. “If given a choice, we’d rather have forestry than a shopping center,” he said. While logging disturbs an area once every eighty years, “Development is every day, all day, forever.”

Snohomish County, 15 miles north of Seattle, will experience a population growth of 47 percent in the next 13 years, according to a recent report. “These people are gonna come. You can’t put a fence up,” said Tom Murdoch, a water resource coordinator with the public works department. “We’ve got to ensure a manner of sound growth.”

A survey of 5,000 acres in Snohomish county showed a loss of 10 to 15 acres of wetlands a month primarily due to development of residential and commercial areas. Wetlands act as reservoirs and trap winter rains. Over the course of the dry summer months, the water is released steadily into the streams.

The loss of wetlands is already causing problems in the county. Because there are fewer “reservoirs,” rainwater runs off the land at higher rates. Rivers can’t handle the increased load. Flood levels reached once every hundred years are now reached every five years.

People with homes in these flood plains are understandably angry about water damage and erosion. Often they appeal to the Corps of Engineers to curtail a river’s flow by building dikes or strengthening the bank by “riprapping.” These “solutions” are no solutions at all but only transfer the problem to someone else’s backyard. Channelization of the river wreaks havoc on salmon habitat as the flows increase, flushing the fertilized eggs from the gravel.

As more rural land is developed problems with sewage and urban pollution will undoubtedly increase.

A National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) report examining two sets of sea-bound juvenile chinook salmon indicates the fish are not, as previously thought, immune to ingestion of toxic pollutants in the rivers. The preliminary study found the PCB liver concentration, bile metabolites and aromatic hydrocarbons of stomach contents to be three times, 20 times and 600 times higher respectively in Seattle’s Duwamish River hatchery fish than hatchery fish from the unpolluted Nisqually River. While no one claims that the results are conclusive, key questions, such as how the elevated chemical content affects the salmon, will be left unanswered until the research team finds adequate funding.

The destruction of salmon’s habitat has not and will probably never end, but even the most cynical observers are finding reason to be optimistic. The successful negotiation of the U.S.-Canada Pacific Salmon Treaty and the Timber, Fish and Wildlife proposal proved that many diverse peoples with different priorities can work together. “If you get the right people in a room, the right mediator and the right information,” said Williams, “you get a win-win situation.”

But this is just the beginning. Observers caution that long-term plans concerning logging, farming and development will have to be formulated for each watershed. This land use planning will involve governmental restrictions on what can be done on private property. Not everyone will agree with those regulations.

A task force charged with improving Puget Sound’s water quality recently proposed fencing farm streams to keep livestock out of the water and away from streamside vegetation.

Before one public meeting in Bellingham, the task force members were met by farmers carrying buckets of tar and feathers. The message from this and subsequent meetings was clear. Those people whose cooperation was imperative for the success of the plan did not want the regulation passed. The proposal was shelved for the time being and an intense public education program was begun.

“Few people maliciously destroy a stream. A lot of them do it through ignorance,” said Tom Murdoch, founder of the “Adopt-a Stream” Foundation. Begun in Snohomish County in 1981, it is recognized as one of the most successful salmon education and habitat rehabilitation groups in the world. Currently 19 community groups and 23 schools have built fishways, cleared debris, fenced streams and incubated salmon with grants from the Foundation.

Murdoch believes public involvement is necessary, especially for school children. “If we can get every school (in the state) involved, we will, in the not too distant future, have an informed electorate that will be able to make better land use decisions,” he said.

When this informed electorate become voters, Murdoch and Williams hope the lessons learned in the last few years will be remembered. That the resources are finite and that there is no longer forty untouched acres just over the horizon.

“We need to look at this earth as something more than some place to pave or some place to build,” said Williams. “Genesis 1:28 says that man should ‘have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air and over every living thing that moves upon the earth.’ “

“Dominion means management,” he adds. “It’s ensuring there will be an earth here when we’re finished.”

©1987 Natalie Fobes

Natalie Fobes, photographer on leave from the Seattle Times, is chronicling the Pacific Salmon and their struggle to survive.