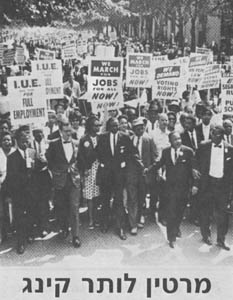

Just a few months out of college, Donna Brazile had one of the best jobs in America. She would be coordinating the 20th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington–the march that had ended with Martin Luther King’s ringing “I Have a Dream Speech” and marked another step in the road leading to passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Like many of the seminal events of the Civil Rights Movement, the March had been a triumph of coalitions. It included Jews, union members, clergy, thousands of liberal whites.

Brazile had been three years old when the first march took place and had always regretted missing out on the excitement of the 1960s–the excitement her parents and grandmother in Louisiana often talked about, of freedom rides and sit-ins. For someone thirsty for history, organizing the 20th anniversary march was a chance to work with some of the most famous names of the past two decades: Bayard Rustin, Andrew Young, Jesse Jackson, Coretta Scott King.

But it soon became apparent that a great deal had changed in 20 years. Brazile found herself enmeshed not in the nostalgia of 1963 but in the politics and disputes of the 1980s. Some blacks wanted representatives from Arab-American groups to appear on the speaker’s platform. Jewish groups vehemently objected. Other blacks felt the “call” or declaration accompanying the March should discuss the Middle East; Jews objected and threatened to withdraw if the declaration criticized Israel. As she desperately set up conference calls from a tiny office in Washington in an effort to patch things together, Brazile found blacks angry at Jews, Jews angry at blacks. In a meeting in Atlanta, Brazile listened as Coretta Scott King, widow of the civil rights leader, talked about the need to reassemble the old coalition that had supported the Civil Rights Movement.

The 23-year-old Brazile turned to her: “Whatever coalition you thought you had doesn’t exist anymore,” she said. “We have to build new coalitions.”

After more than a decade of disputes over affirmative action, Israel, and the goals of the Civil Rights Movement, the younger generation of blacks and Jews is starting to speak up about the once powerful alliance that since the late 1960s has crumbled into disarray, amidst bitter charges and counter-charges.

The upcoming 1988 presidential election is likely to focus on political leaders to see how well they can forge coalitions. But it is failing to these blacks and Jews in their 20s and 30s-too young to have marched with Martin Luther King, people for whom the Civil Rights Movement is only a memory-to determine whether the black-Jewish alliance has a future or whether it is time each group goes their separate way.

Much of what younger blacks and Jews say throws cold water on the notion that black-Jewish cooperation can regain its earlier fervor anytime soon.

“I’m totally bored with hearing the history of Jewish involvement in the Civil Rights Movement,” says Melanie Lomax, 35, a politically-active black lawyer in Los Angeles. “I’m only interested in what’s possible now. The Jewish community’s support of reverse discrimination has undermined affirmative action…Jews see blacks as an underclass. There is a patronizing, condescending attitude.”

Across the country in New York, Marc Stern, 36, a lawyer for the American Jewish Committee, speaking as an individual, echoes the belief that nostalgia over the old Civil Rights coalition holds little sway over blacks and Jews under 40.

“There is sort of a romantic Camelot attitude towards that Civil Rights era that has a lot of emotional power for the older generation of Jews,” says Stern, who was a teenager at the height of the Civil Rights protests in the early to mid 1960s. “It doesn’t have that power for a lot of younger people. The terms of the relationship will have to be renegotiated.”

There are many in both communities who feel that the black-Jewish alliance is simply over. Bitterness over past disagreements and rapidly diverging interests have set blacks and Jews on separate–sometimes colliding–courses, they say.

“My parents have had this group of liberal Jewish friends for as long as I can remember–people they fought with to integrate theaters, restaurants, etc.,” says Lomax. Many younger blacks, she says, “don’t respect my parents’ generation that was so much in the pocket of the Jewish community…Younger blacks are intent on breaking that stranglehold.”

On the campus of UCLA, Rabbi Chaim Seidlerfeller, head of the campus University Hillel, its largest Jewish student group, says Jewish students take a dogmatic line on issues that concern them most, like Israel.

‘There is no willingness among a large number of Jewish students here to hear criticism of Israel on apartheid,” Seidlerfeller says, referring to Israel’s trade with South Africa that has come under sharp attack by blacks. “Their attitude is Israel is right no matter what…They don’t want to hear criticism on apartheid. They’re fed up with the continuous barrage of condemnation” that Israel has undergone in recent years.

Nevertheless, some younger blacks and Jews believe cooperation is possible if the two groups come to the table as equals. Lomax’s unhappiness with black-Jewish cooperation during the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s is widely shared among many blacks and even among some Jews. Younger blacks and Jews say they are uncomfortable with Jews working with blacks as part of, in Stern’s words “the white man’s burden, some kind of noblesse oblige.” Far better, they say, for blacks and Jews to come work together out of common self-interest.

Even in the 1960s, argues Leonard Zakim, executive director of the New England Anti-Defamation League, a Jewish organization, the alliance between blacks and Jews was based on mutual self-interest. The anti-discrimination laws that benefited blacks opened as many, if not more, doors for Jews, he says.

The need for both groups to feel they are getting something out of a coalition is even more important today, Zakim says.

“The only way an alliance is going to evolve is if the representatives of the community act in the self-interest of the community,” says Zakim. “You can’t get people to support a candidate because it’s the right thing to do or because it’s nice.”

Donna Brazile agrees. “My main concern is to do things that help black people,” says Brazile. “Anything that does that I will agree to.”

While the black-Jewish coalition no longer has the power to mass 250,000 people for a march on Washington or send thousands of white students South to help blacks register to vote, it remains a force to be reckoned with, especially in politics. This past November, longtime Civil Rights activist John Lewis defeated another activist, Julian Bond for a Congressional seat in Atlanta, largely on the strength of Jewish swing votes in his district. In Chicago and Philadelphia, Jews provided the victory margins for black mayors in their last elections and played a key role in Chicago Mayor Harold Washington’s successful effort to get reelected this year. On the national level, Jews remain some of the most influential voices in the Democratic party and are many of its biggest fund raisers. The rise of black voting participation is focusing increasing attention on black voting strength in the South and in big cities.

Blacks and Jews are also both tied to the nation’s cities and share a common concern with urban problems such as seemingly intractable ghetto poverty and the need for increased social services. Both groups remain the country’s staunchest domestic liberals. In a 1984 Harris poll, Jews favored the Equal Rights Amendment, a nuclear freeze, increased spending for the environment, and the right to choose an abortion by 70% to 20%. Blacks backed the same issues by 73% to 29%.

In Boston, Zakim and a younger generation of black lawyers and ministers have worked together effectively on issues of common concern such as combating racial attacks against blacks, Jews and Asians, pushing for tough enforcement of anti-discrimination laws, and pressing corporations to hire and promote minority workers. While this may not be as dramatic as marching together on the road from Selma to Montgomery, younger blacks and Jews still interested in cooperating argue it is the best they can hope for. There is room, the optimists say, for compromise on issues that benefit both sides.

“Very few married couples I know go through their lives as starry-eyed as they did in their courtship,” says Stern. “It’s the same way with blacks and Jews. It has to move from a romantic era to a more stable relationship. There will be fights and disagreements. But it will be healthier.”

©1987 Jonathan Kaufman

Jonathan Kaufman a reporter on leave from the Boston Globe, concludes his investigation of’ the broken alliance between Blacks and Jews in America.