The United States Army was still segregated in April, 1945. Blacks fought in separate companies commanded by separate officers. As the war neared an end, allied troops pushed east to Berlin and south toward Austria. General Dwight D. Eisenhower wanted to wrap up the war by June.

Paul Parks, a 20-year old sergeant from the poor, black part of Indianapolis was settling down for the night on the outskirts of Munich when he received word that the next morning he and his troops would be the advance soldiers into a camp called Dachau. Parks assumed “Dachau” was a German army camp. He wondered why his unit was to be first in. They were support soldiers, in charge of building bridges and defusing mines, not combat troops.

Parks had known a handful of Jews before going overseas. There was Gabe Segal, who owned the grocery store in his neighborhood, who had taken him aside once to explain the Star of David and the Hanukah menorah. There were the Jews who lived with him in college, at International House at Purdue University, because Purdue restricted the number of Jews who could live on campus. There was the Jewish soldier at basic training who had given Parks a copy of William Shirer’s Berlin Diary, with its vivid description of German anti-Semitism. But nothing prepared Parks for what he would see the next day.

On April 29, 1945, Parks’ platoon moved into Dachau. As they entered, Jews began drifting out of the barracks, looking almost like ghosts, so emaciated were they. They ran up and began to hug the black GIs. The blacks were stunned by what they saw. The ovens were still warm. Some soldiers became sick. Others were afraid to embrace the Jews for fear they might break.

The reason blacks were sent into this part of Dachau first became clear. Within hours, the American high command would ship in medicine and food to the concentration camp survivors. But the first priority was to clear away the dead bodies the Germans had left behind. Parks’ black platoon, at the bottom of the army hierarchy, was the army burial squad.

As Parks directed the bulldozers into action, he began thinking about stories his mother had told him about growing up in the south, about some things he himself had seen during basic training there. In the middle of Dachau, Parks stood and thought to himself that this was like lynching.

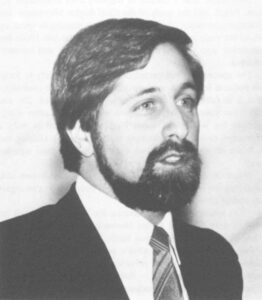

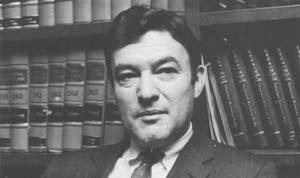

One day in 1961, Thurgood Marshall called 37-year-old Jack Greenberg into his office and told him he would be succeeding Marshall as head of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. Marshall had led the fund for almost 25 years, and to some of its greatest triumphs, including victory in the Brown vs. Topeka Board of Education case that paved the way for desegregation of public schools. President Kennedy was appointing Marshall to the Second Circuit of the U.S. Court of Appeals. In 1967, Marshall would ascend to the Supreme Court. Greenberg had been with the Legal Defense Fund for twelve years. He had worked on part of the Brown case and had traveled around the south on civil rights cases during all that time, turning down offers to go into private practice in New York in order to stay with what he considered the best job in constitutional law in the county.

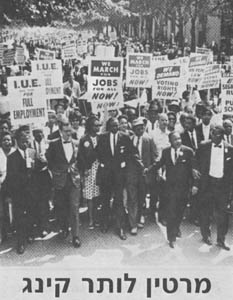

But the appointment of Greenberg, a white, Jewish lawyer, to head the nation’s premier black civil rights law organization, was sure to raise eyebrows. There were other black candidates for the job who could match Greenberg’s legal credentials. The symbolism also seemed askew. In the wake of sit-ins at lunch counters, “freedom rides” to desegregate bus waiting rooms, the ringing oratory of Martin Luther King Jr., shouldn’t blacks be leading the legal fight for black equality?

In many ways, Greenberg’s appointment as head of the Legal Defense Fund was an appropriate symbol. By the early 1960s, a defacto alliance had grown up between blacks and Jews. Today that alliance has flown bitterly apart. From Jesse Jackson’s “Hymietown” remarks to Louis Farrakhan’s denunciation of Judaism as a “dirty religion” and the prominence of many Jews in criticizing affirmative action, it is difficult to see what can bring blacks and Jews back together.

It wasn’t always that way. Throughout the 1950s, officials of local NAACP branches and Jewish groups like the American Jewish Committee and local Jewish Community Relations Councils had worked together in cities across the country to challenge discrimination and draft fair housing laws. Jewish contributions had for years been the major source of funds for the country’s two largest black groups, the NAACP and the National Urban League (indeed, two Jewish brothers, the Spingarns, were two of the most influential founders and shapers of the NAACP). Between one third and one half of whites participating in the ‘freedom rides’ and, later, the massive voting registration drive among blacks in Mississippi in 1964 were Jews. When police dug up the bodies of three civil rights workers killed by the Ku Klux Klan in Mississippi in the summer of 1964-James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner–one, Chaney, was a black civil rights worker from the south while Schwerner and Goodman were Jews from the north. Marshall was appointing Greenberg because he was a fine lawyer and a fine administrator. But the move confirmed for many Jews what they felt intuitively: a burgeoning, seemingly unbreakable, coalition between blacks and Jews.

The lives of Paul Parks-who became a civil rights worker in Boston and in the south and who worked closely with Jews–and Greenberg–who led the NAACP Legal Defense Fund successfully and aggressively for more than 20 years–symbolize the spirit of cooperation that animated blacks and Jews during the early days of the civil rights movement, from the late 1950s to the mid 1960s. Parks and Greenberg each wove together a commitment to civil rights with a pragmatism that constantly pushed the movement forward.

What was it that brought blacks and Jews to the point where they stood side-by-side in the struggle for civil rights? What were their perceptions and expectations of each other? At Civil Rights dinners during the 1960s and 1970s it became customary for blacks and Jews to talk as if they were one people. Both blacks and Jews have been oppressed. Both know the pain of injustice. Let us go forward together. But such comparisons glossed over a world of difference. Though blacks and Jews worked closely together in the civil rights movement from the 1950s to the riots of 1968, they arrived there by very different paths with very different histories.

For American Jews, the commitment to civil rights stemmed from the convergence of three strains of Jewish history: the influx of Eastern European Jews with their commitments to socialism, labor unions and communism; the rise of anti-Semitism in the United States beginning in the late 19th Century; and the Holocaust in Europe in the 1930s and 1940s. For America’s blacks, cooperation with Jews in the Civil Rights Movement was tinged from the very beginning by the ambivalent legacy of earlier encounters between the two groups, encounters that ran the gamut from enduring unfairness and cheating from Jewish-owned businesses in northern ghettos during the week to identifying with Jews and their suffering on Sundays in church.

Jack Greenberg always insisted-and he was right–that it was never pre-ordained that Jews would enlist in the Civil Rights struggles of the 1950s and 1960s or embrace the liberalism of the New Deal-Great Society Democratic party. Reading from a prayerbook, being exposed to Jewish values did not guarantee a political commitment to helping blacks or other minorities.

Unlike the Quakers, or even the blue-blood Protestant Brahmins of Boston, American Jews never had a history of becoming involved in liberal causes, even during the Civil War. Jews were abolitionists, but Jews were also slave owners. A Jewish South Carolina businessman, Abraham Seixas, advertised in 1794 the sale of Negro slaves:

| Abraham Seixas | He has for sale | All so gracious | Some Negroes, male, |

| Once again does offer | Will suit full well grooms | |

| His services pure | He has likewise | |

| For to secure | Some of their wives | |

| Money in the coffer | Can man clean dirty rooms. |

Jews who fought injustice in the United States, focused their battles on the struggle for Jewish rights. In this, they followed a pattern established by Jews in Europe. Shunted into ghettoes, pushed literally to the margins of society, Jews in Europe often survived the hostility of local residents and the Church by negotiating a modus-vivendi with political leaders–ensuring the right to be left alone, to live under restricted conditions but at least to be allowed to stay. Politically, this made Europe’s Jews deeply conservative. A rapid change in politics often imperiled their own position. Mass, uncontrolled political movements could easily turn into anti-Semitic attacks. “Any group larger than a minyan [the 10 men required for prayer],” went a Jewish saying, “looks like a pogrom,” the Russian mob attacks on Jews that took place in the late 19th century.

(A religious factor also played a role in the development of Jewish liberalism and support of Civil Rights. In 1884, the rabbis of the Reform Movement announced their eight-point charter, part of which was a statement on social justice. It declared “we deem it our duty to participate in the great task of modern times, to solve on the basis of justice and righteousness the problems presented by the contrasts and evils of the present organization of society.” This was a break from other Jewish groups and placed the issue of social justice at the forefront of Jewish religious teaching for the next century. In the 1880s, the “evils” of society centered around the power of Big Business and the plight of immigrants, by the 1950s and 1960s, the central problem of society had become the race problem).

The Eastern European Jews who emigrated to America after 1880, unlike the German Jews before them who were relatively well-off, were overwhelmingly poor and working class. They duplicated to a dizzying degree the left-wing groups, bunds, socialist leagues and communist cells they had belonged to in Poland and Russia. By the start of the 20th century in Boston, for example, there was a Jewish-dominated Socialist Labor party, a Jewish Worker’s Educational Club, a socialist Bund that promoted Yiddish but opposed Zionism, a “Territorialist” group that backed Zionism but not a Jewish homeland in Palestine, and a Labor Zionist group that backed a Jewish homeland in Palestine but insisted it be socialist.

These Jews formed some of the most militant labor unions in New York and elsewhere. They called for worker solidarity in picket signs printed in Yiddish and Hebrew. Their theme was brotherhood, without regard to race or religion. Jewish-dominated unions were among the first to open their ranks to black workers. They ran “workers camps” that brought black and Jewish children to the country for summer recreation. The high level of Jewish activism in socialist groups paved the way for the heavy Jewish involvement in the Communist party. The communists emphasized class struggle, and in an effort to unite the working classes proselytized heavily in Harlem. Many of the Communist organizers in Harlem were Jews, and the organizing efforts in Harlem and other black ghettoes in the 1920s and 1930s marked the first time many Jews and blacks came into direct contact.

At the same time radical and left-wing Jews were embracing the idea of union power, class struggle, and uniting with other minority groups to oppose “the bosses,” other Jews were being pushed to more liberal views by their own experiences with discrimination. Up until the 1880s, Jews had faced few barriers in the United States, though, to be sure, there were examples of discrimination. Then, in 1877, a hotel in Saratoga Springs refused to admit Joseph Seligman, a German Jewish banker. The action stirred a storm of criticism, but within a few years discrimination against Jews had become widespread, with Jews shut out of housing in “better” neighborhoods; and prevented from attending universities like Harvard, Yale and Columbia because of quotas. A revived Ku Klux Klan targeted Jews, Catholics and blacks.

Thus when Protestant “reform” groups in the 1850s crusaded for a return to strict Sunday “blue” laws, Jews opposed it. They did not argue, as they would a hundred years later, that this was an unconstitutional mixing of church and state. Rather, Jews argued that they observed their Sabbath on Saturday and therefore should be exempt. It was an argument that met with some success.

America’s Jews, like other immigrant groups, were also too busy trying to make their own way in America to worry much about others. The concern and compassion that Jews manifested–the societies that lent money, buried the indigent, taught English, helped the poor–were designed to help fellow Jews and newly-arriving Jewish immigrants. Jewish energy was focused on Jewish survival.

All this began to change as a result of three factors, three streams that converged in the late 1940s. First was the flood of Jewish immigrants from Russia and Eastern Europe between 1880 and 1920 who brought with them radical ideas about socialism, communism, and the power of labor unions. Essential to this ideology was the notion of brotherhood, of uniting together all workers regardless of their religion or the color of their skin. Second was the rise in discrimination against Jews beginning in the 1880s, reaching a peak in first thirty years of the 20th century with the lynching of a Jewish businessman, Leo Frank, and the rise of anti-Semitic organizations like Father Coughlin and the Ku Klux Klan. This made Jews identify more easily with other persecuted groups, especially blacks. Third was the virulent rise of Nazism in Germany and the horror of the Holocaust, making Jews more sensitive to cries of black injustice.

As they had in the past, Jews at first responded to these attacks by setting up organizations to defend Jewish interests. The American Jewish Committee was set up in 1906, the Anti-Defamation League in 1913, during Leo Frank’s murder trial, the American Jewish Congress in 1918.

But events soon forced Jews to realize that their appeals were falling on deaf political ears. The conservative wings of both the Democratic and Republican parties refused to renounce the violence of the Ku Klux Klan, in part because of the power and influence of southern senators. The pace of anti-Semitism increased. In the 1920s, Henry Ford’s Dearborn Independent spewed forth anti-Semitism. For the first time, Jews and Jewish groups began identifying with issues affecting other minorities, especially blacks. Jews became influential in establishing the NAACP. Louis Marshall, head of the American Jewish Committee, argued on behalf of the NAACP in the Supreme Court against restrictive housing covenants that discriminated against blacks and Jews. The Jewish Daily Forward, the Yiddish worker’s newspaper on the lower east side of New York compared race riots in St. Louis in 1917 with pogroms in Russia.

Deprived by Prejudice

“By the 1930s,” writes historian Oscar Handlin, Jews “considered themselves one of the ‘minorities,’ that is, one of several groups to some degree discriminated against. Along with the Negroes, the Catholics, and many of the foreign-born, they were deprived by prejudice of the equal opportunities of American society.” And, like those other groups, Jews by the 1930s had found a political home and a political program to overturn those injustices: Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal of the Democratic Party.

The third factor that set the stage for the sympathy of many Jews for the Civil Rights movement was the Holocaust. The systematic destruction of Europe’s Jews showed the consequences of unchecked prejudice and hatred. When the American Jewish Congress and American Jewish Committee launched studies in the 1940s of the dangers of prejudice in America, both drew heavily on the work of German-Jewish refugee scholars and psychiatrists. The Holocaust reshaped the American Jewish view of the world. What had happened in Germany, some feared, could happen here. As the 20th century’s ultimate victim, Jews would more easily identify with other victims of oppression and injustice. The memories they carried with them after World War II made them more sensitive to cries of injustice from blacks and other minorities–for once persecution started, many Jews remained convinced that it would end up directed at them.

When Paul Parks stumbled into Dachau in 1945, he knew something about Jews from his talks as a child with Gabe Segal and his reading of Berlin Diary. In this, Parks differed from many blacks his age. In the South, most blacks did not know Jews at all. There were too few of them, and they were concentrated in the cities. Even in the North, where blacks and Jews had rubbed shoulders in the communist party, in the NAACP, in grocery stores and pawn shops, they really didn’t know each other very well. Black attitudes towards Jews also reflected black attitudes towards, and expectations of, whites–attitudes shaped by the history of blacks in this country.

The black fascination with Jews had its roots in the Christianity, a Christianity which, ironically, had been forced upon many slaves by their slaveowners but grew to be one of the most important forces in the black community.

“The Jewish boys in high school were troubling because I could find no point of connection between them and the Jewish pawnbrokers and landlords and grocery store owners in Harlem,” James Baldwin wrote in 1962. “I knew that these people were Jews–God knows I was told it often enough–but I thought of them only as white. Jews, as such, until I got to high school, were all incarcerated in the Bible, and their names were Abraham, Moses, Daniel, Ezekiel, and Job, and Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego. It was bewildering to find them so many miles and centuries out of Egypt.…”

The teachings of Christianity left an ambivalent legacy. On the one hand, the Jews, as the people who had killed Christ, were beyond salvation. They were doomed to be the perpetual outsider. Wrote Richard Wright in Blackboy, his autobiographical tale of growing up in the South:

“All of us black people who lived in the neighborhood hated Jews, not because they exploited us, but because we had been taught at home and in Sunday school that Jews were Christ-killers.”

Jew, Jew, Jew What do you chew?“Or we would form a long line and weave back and forth in front of the door, singing:

Jew, Jew Two for five That’s what keeps Jew alive“Or we would chant:

Bloody Christ killers Never trust a Jew Bloody Christ killers What won’t a Jew do?”

At the same time, another message came through the Bible about the Jews. Like blacks, Jews had once been captives in a strange land, awaiting someone to lead them to freedom. Negro Spirituals sang “Let My People Go” and of crossing the River Jordan to lead them into the Promised Land. “The Negro identifies himself almost wholly with the Jews (considering) that he is a Jew, in bondage to a hard taskmaster and waiting for a Moses to lead him out of Egypt,” wrote Baldwin.

Layered on top of this religious exposure to Jews were economic encounters, especially in northern cities. Parks’ family never had a bad word to say about Gabe Segal. But many other blacks did become angry at store owners who charged them too much, landlords and rental agents who demanded too much for a tiny, filthy apartment.

“When we were growing up in Harlem our demoralizing series of landlords were Jewish and we hated them,”’ wrote Baldwin. “We hated them because they were terrible landlords and did not take care of the building. A coat of paint, a broken window, a stopped sink, a sagging floor, a broken ceiling, a dangerous stairwell, the question of heat and cold, of roaches and rats–all questions of life and death for the poor, and especially for those with children–we had to cope with all of these as best we could. Our parents were lashed down to future-less jobs, in order to pay the outrageous rent. We knew that the land lord treated us this way only because we were colored, and he knew that we could not move out. The grocer was a Jew and being in debt to him was very much like being in debt to the company store. The butcher was a Jew and, yes, we certainly paid more for bad cuts of meat than other New York citizens, and we very often carried insults home, along with the meat. We bought our clothes from a Jew and, sometimes, our second-hand shoes, and the pawnbroker was a Jew–perhaps we hated him most of all.”

And yet (the contradictions existed side-by-side, especially in the North), Jews were also often the only people who would hire blacks, or extend them credit. Jews worked to desegregate all-white suburbs. Many of the Jews whom blacks came into contact with–Jews as communist party organizers, as backers of the NAACP, as labor union officials–were kind, compassionate and backed black causes. What image of the Jew to choose? Killer of Christ or oppressed slave? Exploitive store owner or socialist organizer? White enemy or white friend?

The histories of blacks and Jews had brought them side-by-side as the Civil Rights struggle began in the 1950s. But those histories contained the seeds of problems that would develop later.

©1986 Jonathan Kaufman

Jonathan Kaufman, a reporter on leave from the Boston Globe, is investigating the broken alliance between Blacks and Jews in America.