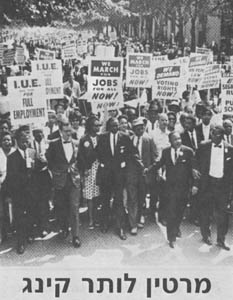

CHICAGO–it was wretchedly hot that July Sunday in 1966. The temperature soared to 98 degrees. More than a half million people jammed the beaches. But along State Street and the Outer Drive, Roz and Bernie Ebstein marched slowly towards Soldier’s Field, carrying a banner from the American Jewish Congress, demonstrating with Martin Luther King, Jr.

Civil Rights leaders had dubbed the day “Freedom Sunday” in anticipation of a giant march and rally to protest housing and employment discrimination in Chicago. The brutal heat combined with a cooling ardor towards the Civil Rights Movement kept the turnout far below expectations–30,000 people, less than one-third of the 100,000 King and his organizers had hoped for.

The Ebsteins had come to the rally from their small wood and brick duplex house in Marionette Manor, in Chicago’s Far South Side, a white, middle class neighborhood about 40 percent Catholic, 40 percent Jewish, and 20 percent Protestant that had seen its first black family move in the previous year. The Ebsteins were determined their neighborhood was going to be a model for integration. They had watched with distaste as an all-white neighborhood bordering theirs–Trumbull Park–and even Mayor Richard Daley’s own neighborhood of Bridgeport had greeted the attempt of blacks to move in with stonings, threats and firebombings. Marionette Manor would be different. Roz and Bernie Ebstein were marching that day to put their idealism into practice. They were going to make civil rights work for themselves and their children. Before the march began, Bernie had sat in a room across from King. Twenty years later he would talk about that moment, joking that it was the closest he had ever gotten to a great man, but also proud that he had had the chance to sit so close to Martin Luther King.

Twenty years later, Bernie and Roz Ebstein would be living in an all-white suburb, 40 miles and a world away from Marionette Manor. Their old neighborhood would be a black neighborhood, the synagogue where they worshipped shut down and turned into a public school, the Jewish Community Center that Roz’s brother helped run closed up and moved further north, to the more affluent Hyde Park area near the University of Chicago. These days, as they recollected in a series of interviews recently, the Ebsteins’ free time is increasingly dominated by Jewish concerns, as co-music directors of their suburban synagogue. Roz still commutes to the South Side where she teaches early childhood education at a predominantly black community college. On her trip from her home to her work she sometimes reflects that she lives her life today in two different worlds, a black world at work and a Jewish world at home-in contrast to the King rally 20 years ago when she locked hands with protesters and sang “We Shall Overcome” with its chorus promising “black and white together.”

Speak to leaders and politicians about the dilemma of Black-Jewish relations–which nearly ruptured the Democratic party during the 1984 campaign and is a continuing source of tension in American liberal circles-and they are likely to discuss issues like affirmative action and American policy towards Israel. But for many blacks and Jews, the seeds of tension, like the seeds of cooperation, were sown in personal encounters. For blacks, these often took place in jobs where they worked with or for Jews, in stores in ghettos, in schools and colleges and universities. For many Jews, the most vivid form of contact with blacks has taken place in neighborhoods that were once largely Jewish and changed during the 1950s and 1960s to become largely black: Roxbury and Mattapan in Boston, Brownsville in Brooklyn, the South Shore and the Far South Side in Chicago.

In some cases, Jews responded to the change in what they considered to be “their” neighborhood with anger; in other cases with quiet bitterness; in cases like the Ebsteins with hope and optimism that slowly turned into frustration and puzzlement. Liberal Jewish activists like the Ebsteins, who seemed so numerous in the 1960s, are fewer and further between these days. So are liberal activists of all religions and all colors. Why? Beyond the politically charged and attention-getting issues of affirmative action and support for Israel, the rise of Reagan-style conservatism and disillusionment with old-style liberalism, some of the reasons lie in the streets between the neat wood and brick houses of neighborhoods like Marionette Manor.

Nineteen sixty-six was a pivotal year for the Civil Rights Movement. Following his march from Selma to Montgomery in 1965 that led to passage of the Voting Rights Act outlawing poll taxes and literacy tests in the South, King decided to shift his attention to the North, to crack the de facto segregation and discrimination rife in northern cities. A tough challenge under the best of circumstances, bringing the Civil Rights Movement north was made even tougher by a growing white backlash against black demands and a shrinking base of white support. Nevertheless, King persevered and in January, 1966 moved into a slum apartment on Chicago’s black West Side to symbolize his concern for the poor.

By the time King held his Freedom Sunday march in Chicago in the summer of 1966, riots had ripped apart the Watts ghetto in Los Angeles in 1965 and had flared in New York in 1964. In the weeks after the King march, they would break out in Chicago’s West Side too, despite strong efforts by King to stop them.

Like many whites, Jews were shocked and unnerved by the violence–especially since much of the looting was directed against Jewish-owned stores in the ghettos and was often accompanied by references to “Jew landlords” and “Jew merchants.” In a march in Mississippi in June of 1966, Stokely Carmichael, the newly elected leader of SNCC (the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee) issued a call for “Black Power.” Despite the efforts of King and other moderates, the slogan caught on among younger, more militant blacks. Beginning with the Montgomery bus boycott in 1956-57–indeed, reaching back to the founding of the NAACP in 1909-Jews had given a great deal of money to the Civil Rights Movement and provided many of its best white volunteers. As much as 75 percent of money funding SNCC, CORE (the Congress of Racial Equality) and other groups came from Jewish givers. Jewish lawyers made up the bulk of white lawyers, freedom riders and volunteers canvassing the South and defending black demonstrators as they fought for the right to vote and to use “white-only” restaurants and bus stations. The growing militancy among blacks, the demands for economic as well as political equality, troubled many Jews. In an article in the Jewish magazine Commentary–soon to become the cutting edge for Jewish “neo-conservatives”–the Jewish sociologist Nathan Glazer warned in 1964 that Jews were being “confronted for the first time with demands from Negro organizations that, they find, cannot serve as the basis of a common effort.” Glazer was prophetic. By 1966, many Jews were becoming disenchanted with the Civil Rights Movement and cutting back their levels of support.

But Bernie and Roz Ebstein still believed. They believed in civil rights, believed in equality and believed in integration. A lean, almost ascetic-looking man who combined a love for math with a love for classical music, Bernie had been born in Germany and was nine years old during Crystallnacht when the Nazis, in an anti-Semitic orgy, smashed the windows of Jewish-owned stores and desecrated synagogues and Jewish schools. That night, Bernie’s father just missed being taken away by the Gestapo. His family fled to America. They settled in a small town in southern Illinois where the daily teachings of the wonders of American democracy in the classroom clashed with the realities that it was dangerous for a black to be caught in town after sundown. Bernie believed in civil rights because he believed the people who said “n…..” had the words “dirty Jew” on the tips of their tongues–a belief that was confirmed one day in 1966 when Bernie joined a group of civil rights protesters for a march through the all-white, working class East Side of Chicago. Onlookers jeered and threatened the protesters. “If it hadn’t been for the police lines, we would have been assaulted,” Bernie recalls.

A Matter of Principle

Roz Ebstein is Bernie’s physical and emotional opposite. Talkative and outgoing, she moves with an energy that suggests she has activism in her genes. She had grown up on Chicago’s West Side and, when she was 11, had been taken by her mother to a demonstration protesting the treatment of Jews in Europe. By the time she was 16 she was going to protests on her own, demonstrating in front of the British embassy for the creation of the state of Israel. Years later she still treasured a picture of her taken at that demonstration and would show it proudly to her children.

The Ebsteins met as students at the University of Chicago. It was through their activities with the American Jewish Congress, which attracted politically liberal Jews and put civil rights high on its agenda, that they joined the march with King and decided to fight to keep Marionette Manor integrated. For the Ebsteins, the decision to stay in Marionette Manor while many whites around them were moving out to all-white suburbs was a matter of principle. “We decided we were going to make a stand when a lot of people were leaving,” says Roz. “You would listen to a lot of them talk about blacks and it would make you cringe.”

In the months after King’s march, the Ebsteins held meetings in their own living room and in the living rooms of friends to discuss ways to keep Marionette Manor integrated. Some all-white Chicago neighborhoods were using violence and intimidation to stop blacks from buying or renting homes on their streets. The challenge facing Marionette Manor was different: white flight. No violence marred the arrival of black families in Marionette Manor beginning in 1965. Instead, white families began to move away. In order to make integration a reality, the Ebsteins believed, the whites who still lived in Marionette Manor in 1966–making up well over half the population–had to agree to stay.

The Ebsteins were in the Civil Rights Movement because they were Jewish. Their commitment stemmed from Bernie’s experiences in Germany and from what they called the “prophetic tradition” of Judaism which taught them to fight against injustice. And so Bernie, who was vice president of his temple, had a large document prepared that declared “We the undersigned are prepared to stay.” He went from door to door to get members of his congregation to sign it. He spoke to Rabbis and members of other Jewish temples in the area, trying to convince them to stay as well. Unlike many of their friends, the Ebsteins decided to keep their two sons in the public schools, believing that the only way to keep good schools was through parent involvement.

And yet, despite the meetings, despite the petitions, the whites of Marionette Manor-Jews, Catholics, Protestants kept moving out. Real estate agents kept pestering the Ebsteins to sell, intimating that housing prices would fall as more blacks moved in. “You’d get a phone call from a real estate company or someone knocking on the door saying I just sold a house, I’d like to sell yours,” says Roz. “That would happen a lot.” It was a pattern repeated in cities across the country: Realtors stampeding whites into selling their homes, banks “redlining” entire neighborhoods making mortgages harder and harder to get, insurance companies raising premiums. In 1969, three years after the King March, Roz came home from a vacation and found that eight of her white neighbors on her street had sold their homes while she was away.

Still. the Ebsteins were determined to stay. This was their home, the temple where they were determined to make their stand. The National Conference of Christians and Jews even brought school children in from the suburbs on “field trips” to visit local synagogues to hear members talk about what it was like to live in an integrated city neighborhood.

A Different Experience

The Ebsteins’ children, however, were undergoing a different experience. The slogan “black and white together” wasn’t working out as smoothly in practice as it had seemed on the protest marches. All three children had black friends, but Steven, their youngest son who was in grammar school at the time, didn’t see the great alliance that had brought his parents to marches and civil rights demonstrations. “I felt from the first time that blacks moved into my old neighborhood that there were big differences,” between the black and Jewish students, says Steven. “They didn’t have the same values. We weren’t natural allies.” As so often happened in neighborhoods changing rapidly from white to black, the schools in Marionette Manor deteriorated, a result of inattentiveness from city officials, new problems brought in by the new, often poorer, black residents and the presence of some bad kids.

By 1970, so many Jews had left Marionette Manor that the Ebsteins’ temple closed down. Soon the Jewish Community Center moved. The Ebsteins took Steven out of public school and put him in a private Jewish day school. Their other son remained in public school, however, and one day a black student pulled a knife on him in the hallway.

That was the breaking point. It had become too much for the Ebsteins. They decided to sell their house and move. Many of their friends who had left wondered why they had waited so long. Others, who stayed, believed they had left too quickly.

It would be too easy-and wrong-to see the Ebsteins’ experience as a variant of that old 1960s joke: a conservative is a liberal who is mugged–or, in this case, whose children are mugged. Unlike many of their friends who left Chicago’s South Shore and Far South Side, the Ebsteins did not become bitter. Bernie believes that keeping whites in Marionette Manor for the five years they did was a victory; many neighborhoods in Chicago turned from all white to all black in just two years. On issues like affirmative action the Ebsteins still find themselves more liberal than some of their Jewish friends. Roz remains deeply committed to her teaching at the largely black community college. And yet, the Ebsteins acknowledge that they are not nearly as interested in social issues and local affairs as they once were. They don’t get involved at all in activities in their suburban town of Highland Park.

The experience of the Ebsteins offers a painful paradox to liberals. The Ebsteins fought the good fight, yet they still had to leave their neighborhood. Like many liberals, they are frustrated and somewhat puzzled by the way the dreams of 1966–of equality, integration, a harmonious and just society–failed to come to pass. “We felt our way through the whole period as Jews, as committed Jews…as strong political liberals in this country,” says Roz.

Somehow, that wasn’t enough.

©1987 Jonathan Kaufman

Jonathan Kaufman, a reporter on leave from the Boston Globe, is investigating the broken alliance between Blacks and Jews in America.