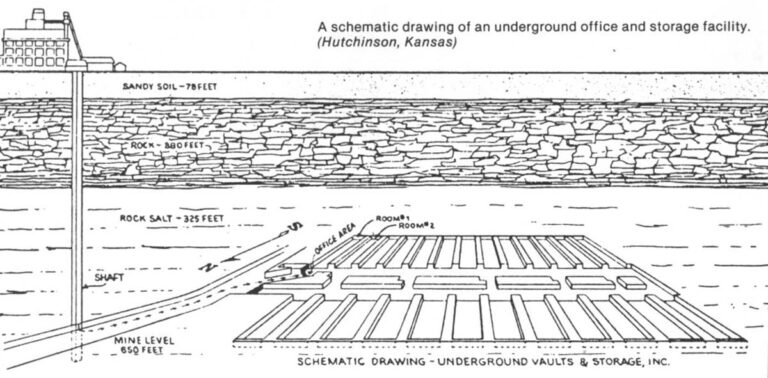

HUTCHINSON, Kan.–Six hundred and fifty feet beneath the Kansas prairie, in a mined-out section of a working salt mine, a man in a gray plaid suit sits at a telex machine typing out and receiving messages. This is only a test-the man comes to the salt mine two times a year for a communications drill. But if a nuclear attack had been launched against the United States, the messages he is sending and receiving would be devoted to re-establishing the services of the Federal Reserve Bank in the devastated country.

“A nuclear attack would be awful,” says John Nolan, the emergency preparedness coordinator for the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, who is running the test in the salt mine. “But there will be survivors. We know that.”

And the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, along with the rest of the Federal Reserve System, has made preparations to provide financial services for those survivors.

“The mechanisms are set up to process checks and provide currency,” said Marvin Mothersead, vice president of the bank in Kansas City. “The basic functions to keep society moving are provided for.”

Whether it makes any sense to plan for processing checks after a nuclear war is a matter of some debate. “The social fabric upon which human existence depends would be irreparably damaged [by a nuclear war],” asserted the International Physicans for the Prevention of Nuclear War, a multinational group of medical researchers, after its first congress in Virginia early this year.

On the other side of the argument, a consultant’s report prepared in 1979 for the Federal Emergency Management Agency asserted, “Years of research have failed to reveal any single factor that would preclude recovery from nuclear attack,” and federal civil defense planners have for years urged financial institutions and other corporations to make plans for nuclear war survival and recovery.

“Emergency preparedness is directed not only toward physical survival but also toward preservation of the basic values of the Nation,” says the National Plan for Emergency Preparedness, which was issued in 1964 and is now being revised. “Consequently every effort should be made to … continue a basically free economy and private operation of industry, subject to governmental regulation only to the extent necessary to the public interest.”

A series of federal directives dating back to the 1950s spell out the responsibilities of banks after a nuclear attack. Many of those directives are contained in a red loose-leaf binder marked “Emergency Operating Letters and Bulletins” that the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City has sent to every commercial bank in its district. One bulletin instructs banks to continue selling U.S. Savings Bonds “in a time of national emergency as every source of funds available will be required to finance the Federal Government.” Banks are also advised that, if they need cash “during the immediate postattack period,” they should raise funds by borrowing against government securities they hold rather than trying to sell the securities in an “unfavorable market.”

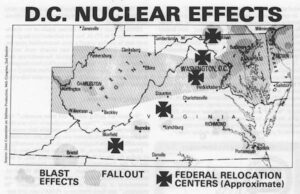

The red binder includes lists of banks in the Kansas City federal reserve district that will distribute currency and serve as check agents “in the event that the regular Federal Reserve banking facilities are rendered inoperable by enemy attack. ” To make that circumstance less likely, however, the bank has designated its branches at Oklahoma City, Omaha and Denver to take over (in that order) if the Kansas City head office is destroyed. In the Kansas City building itself, huge basement vaults have been earmarked to serve as fallout shelters, and supplies of dehydrated food, water, medicines, cots and gas masks have been laid in. Finally, there is the fallback office 650 feet beneath Kansas.

Subterranean Warehouse

The underground office is a room about 20 feet wide and 60 feet long with two walls of plasterboard, one wall of cinder blocks and one wall of whitewashed salt. It is leased from Underground Vaults and Storage, a vast subterranean warehouse operating within the mine of the Carey Salt Company in Hutchinson, Kansas.

“Our emergency operating center used to be in Topeka,” John Nolan said over a lunch of heated TV dinners in the UVS employee dining room. “But in 1961 the government ran a test exercise, and the results showed Topeka being hit pretty hard by the Russians. We went to the Department of Defense for targeting information and decided Hutchinson was not a high-risk area.

The bank’s quarters in UVS are equipped with 14 steel desks, an assortment of antiquated typewriters and handoperated calculating machines, a ham radio and the telex machine that Nolan used to contact the relocation centers of the other 11 federal reserve regions, most of which are also underground. As he typed on it, a Muzak version of “Moon River” was piped in by a speaker in the ceiling.

Adjoining the office is a vault filled with microfiche copies of bank records, a fresh batch of which is sent down every day. “We used to send a team down here during the tests to reconstruct the records to see if it could be done, ” Nolan said. “We stopped doing it because of budget cutbacks, but it always worked.”

Elsewhere in the mine, the bank has stockpiled enough food and other supplies to provide for 400 bank employees and family members for two weeks. The bank employees have been selected and represent every bank department. (One secretary was taken off the list by Nolan because she admitted to being claustrophobic.) They are supposed to rush to Hutchinson, which is 225 miles from Kansas City, upon receiving early warning of a nuclear crisis from the federal government.

What if there’s not time for everybody to make it?

“There’s a junior college here,” Nolan said. “In a war situation, we could acquire people and equipment from it.”

And what if there’s not time for anybody to make it?

“We’ll just go down to the basement of the Kansas City building. But the records will be safe here anyway.”

As a quasi-governmental agency, the Federal Reserve Bank is held to strict standards of nuclear war preparedness, but the government encourages private businesses as well to make emergency plans. “Every industrial facility should be prepared to cope with the hazards and disasters of today’s complex world,” advises the federal civil defense agency’s Disaster Planning Guide for Business and Industry. It notes that “storms, fires, explosions, sabotage, civil disturbances, and possible nuclear attack all pose continuing threats,” and it advises corporations to protect vital records, write out emergency management succession lists, establish alternate headquarters and make other disaster preparations.

Two decades ago, at the height of the Cold War and civil defense consciousness, such advice was widely followed. Employees of Shell Oil in the Houston area were issued yellow wallet cards listing the phone numbers of emergency reporting centers “established as a means for you to contact the Company in case of a nuclear attack…” (Space was left on the back of the card for the employee’s blood type.)

In the same era, Standard Oil of New Jersey set up an emergency headquarters in a former rest home in Westchester County 30 miles from Manhattan. According to an admiring account in the December 1958 issue of Fortune, the beds in the 50 bedrooms were kept made up at all times, and provisions included a hospital room and a locker full of Scotch.

Since then, interest in civil defense has waned among some corporations. “I had one of those cards,” recalls Don Baron of Shell’s office of corporate records management. “I had it till it wore out, I suppose.” In 1975, Baron presided over the closing down of a three-level emergency company headquarters inside Iron Mountain in upstate New York that included bedrooms, a dining room and, according to one company publication, a “home-like” kitchen. “Our basic philosophy changed in the late 1960s,” Baron said. “We don’t feel it’s practical to protect against something that can’t be protected against.” Shell does, however, maintain a vital records storage facility in Louisiana. “Records that will maintain the integrity of the company will be safeguarded in an area outside the holocaust,” Baron said. “And the records can be reconstructed if someone survives.”

Standard Oil of New Jersey, now known as Exxon, still takes steps to improve the chance that someone will survive, and that that someone will be an officer of Exxon. “The Westchester site no longer exists,” an Exxon spokeswoman said, “but Exxon does have contingency plans that would relocate key executives at various locations some distance from New York City. I was not told where they are. The security department is very cautious about this.”

Exxon’s corporate bylaws take pains to insure that any executives who do survive a nuclear attack will be legally qualified to conduct business. Section 4 of Article 11, which “shall be operative during any emergency in the conduct of the business of the corporation resulting from an attack on the United States or any nuclear or atomic disaster or from imminent threat of such an attack or disaster,” authorizes the board of directors to relocate company headquarters, to operate with a reduced quorum, and to make up that quorum if necessary with designated stand-ins “who are known to be alive and available to act.”

More companies may soon reverse the trend away from civil defense, partly in response to reports in recent years that the Soviet Union’s civil defense system is prepared to safeguard factory workers and machinery. “Soviet measures for protecting the work force, critical equipment, and supplies and for limiting damage from secondary effects [of nuclear explosions] could contribute to maintaining and restoring production after an attack,” the Director of Central Intelligence reported in a public statement in 1978. He concluded, however, that ‘those measures … for the protection of the economy could not prevent massive damage.”

Nevertheless, a study conducted by the Boeing Corporation and published this year asserts that “industrial protection of U.S. industry is technically feasible and could be implemented at a reasonable cost.” The Boeing researchers arrived at that conclusion after such experiments as building two mock factories at a Defense Nuclear Agency test site. The factories were stocked with used drill presses and other industrial equipment. In one of the buildings, the equipment was packed in protective material and then buried in dirt. The building was partially buried too. Then a non-nuclear explosion equivalent to 100 tons of TNT was ignited. The equipment in the unprotected factory was blown to bits, but the buried equipment was repaired after four days’ work.

The study concluded that a significant percentage of American industrial capacity could be protected from nuclear destruction if factories would take the time now for some advance planning, training, and stockpiling of protective materials to be hurriedly wheeled out in an extreme international crisis. Boeing itself, however, according to a company spokeswoman, has not taken those precautions.

One company that has long taken seriously the idea of “hardening” its facilities against nuclear attack is AT&T. “In the mid-1960s” said Art Ammon, network operations manager of AT&T’s Long Lines department, “we were installing a lot of interstate cable facilities, and we constructed a number of underground buildings. We were consciously trying to build plant [facilities] that would survive.”

In addition to underground operating and relocation centers, AT&T buried much of its long distance cable four feet deep. Key transcontinental cables were routed around major cities that would be prime Soviet targets, and selected microwave towers were specially strengthened.

“In recent years,” Ammon said, “as has been the case everywhere, we have relaxed to a certain extent. Now the whole issue is being reexamined. We have gone out and surveyed every one of our relocation centers, and we’re working on a set of recommendations for all the Bell companies. The system is not in disarray; we’re talking about some fine-tuning. We may even be making some improvements in Netcong.”

Netcong, New Jersey, is the site of AT&T’s National Emergency Control Center. Located 15 miles north of the Long Lines operations center in Bedminster and 40 miles from corporate headquarters in New York City, Netcong is marked on the surface only by a modest yellow brick building the size of a large garage. Visitors are buzzed in through two doors, walk down four flights and then pass through two heavy vault doors that open automatically one at a time (and could leave an unwelcome visitor stranded in the dead space between them).

Shock Mounting

Netcong works every day as a switching and control center for long distance calls, which pass rapidly and silently through banks of 11-foot-tall multiplex switching units. The units are hung from the ceiling by heavy steel springs and tethered to the floor with thick rubber bands. If the building were struck by a massive blast wave, the rubber bands would snap and the switching equipment would swing, cushioned by the springs, from the ceiling.

All of the equipment at Netcong is shock-mounted, including the toilets, and the building is stocked with enough food, fuel and other supplies to run for a month cut off from the outside world.

Before being cut off, however, plans are for it to be staffed by personnel from the Bedminster operations center down the road and by top corporate executives. The Bedminster staff would take over a large and now unpopulated room that is equipped with desks, phones, computer terminals and everything else needed to monitor and route calls through the nation’s long distance telephone network, or what is left of it. An adjoining large open office lined with plain steel desks is reserved for corporate executives. “It’s rather spartan,” admits Netcong Operations Manager Gene Koppenhaver, “but hopefully we’ll never have to use it.”

But there are some minor perquisites of rank even at Netcong. A small office next to the emergency control center contains two desks only. One bears a nameplate reading, “Chairman of the Board-Mr. Brown.” The second-and slightly smaller -desk’s nameplate reads, “President AT&T-Mr. Ellinghaus.”

The nameplates are kept up to date.

©1981 Ed Zuckerman

Ed Zuckerman is investigating the plans and planning for nuclear war.