WASHINGTON, DC–The last film millions of Americans may ever see is a 27-minute animation called “Protection in the Nuclear Age.” Produced by the Federal Civil Defense Agency, the film is available for public viewing now, but it is specifically designed to be shown on television if a nuclear attack against the United States is ever considered likely. “We live in a world of tension and conflict…” the film’s narration begins, as a picture of the earth floating peacefully in space appears on the screen. “We must therefore face the hard reality that someday a nuclear attack against the United States could occur.”

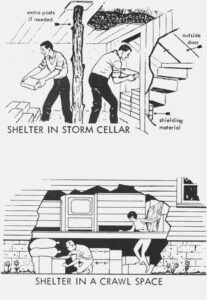

To prepare viewers for that day, the film offers a sample and a description of the siren signal (“a 3-to 5-minute wavering sound”) that means enemy missiles are on their way. The film tells people how to react (“take cover…take a battery-powered radio with you”), includes a brief tutorial on the effects of nuclear detonations, and offers instructions for the construction of improvised fallout shelters. “The greatest danger,” the narration concludes, “is hopelessness–the fear that nuclear attack would mean the end of our world–so why not just give up, lie down and die? That idea could bring senseless and useless death to many–for protection is possible.”

To prepare viewers for that day, the film offers a sample and a description of the siren signal (“a 3-to 5-minute wavering sound”) that means enemy missiles are on their way. The film tells people how to react (“take cover…take a battery-powered radio with you”), includes a brief tutorial on the effects of nuclear detonations, and offers instructions for the construction of improvised fallout shelters. “The greatest danger,” the narration concludes, “is hopelessness–the fear that nuclear attack would mean the end of our world–so why not just give up, lie down and die? That idea could bring senseless and useless death to many–for protection is possible.”

“Protection is possible.” That message seems modest enough to American civil defense planners in the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which announced in March a $4.2 billion program to plan the evacuation of more than 400 American cities in the event of imminent nuclear war. But FEMA planners are frustrated that many people are questioning the value, and values, of civil defense. “Given the bubbling opposition right now to anything dealing with nuclear war, there’s a kind of almost blind revulsion,” said James Holton, FEMA’s director of public affairs. “People who in the past would have been middle of the road or in favor of increasing defenses are now saying nuclear war is horrible and we must do everything to prevent one. Our problem is that they won’t take the next step and say, ‘But if there is one…’ A lot of people are saying we shouldn’t even think about it.”

Holton referred specifically to the massive anti-nuclear weapons demonstrations in Europe, a recent meeting of American Catholic bishops that expressed strong opposition to any use of nuclear weapons, and groups like Physicians for Social Responsibility that have publicized what they consider would be the overwhelming destructive effects of a nuclear war. “There is no effective civil defense,” one PSR publication states. “The blast, thermal and radiation effects would kill even those in shelters, and the fallout would reach those who had been evacuated.”

Civil defense planners do not argue that nuclear war would be a picnic. “Everyone agrees that a nuclear war would be an unparalleled disaster,” FEMA has stated. “But it need not be an unmitigated disaster….Civil defense preparations can make a difference of tens of millions in the numbers of people surviving even a large-scale nuclear war.”

It would probably take a nuclear war to determine for certain just how effective civil defense can be, but it is clear right now that civil defense has a public relations problem. Sober-minded critics like Physicians for Social Responsibility attack civil defense on its merits; others simply ridicule it. There is the case of the study published last fall by two government civil defense researchers who looked at the expected radiation-caused cancer rate among nuclear war survivors and concluded that the rate could be reduced by sending older people out of fallout shelters first to perform necessary tasks. Thus, they said, “the bulk of the [radiation] dose is shifted to those who have less to lose in terms of total life expectancy.” This, to the scientists, was only prudent common sense, but it inspired a satirical, nationally-syndicated column by Mary McGrory speculating about those “among our senior citizens …who would be extremely irascible about being strapped into their walkers and sent forth into the ashes with a shopping list of uncontaminated items….” Maggie Kuhn, founder of the Gray Panthers, was quoted as saying she found the study “shocking.” And the cause of civil defense was not advanced.

James Holton acknowledges that that kind of public reaction has affected FEMA’s style of operation. “Although it’s our responsibility to plan civil defense for a nuclear war,” he said, “we have to go about it in a low-key way, at least for now…But if there’s ever a ‘surge’ situation, with an international crisis galvanizing everybody into action, I don’t think we’d have much difficulty being heard.”

FEMA’s planning for that eventuality includes both a number of civil defense programs and the means to tell people about them. (“In civil defense,” Holton said, “nothing is more important than public information.”) Here, in rough chronological order, are some of the things that are supposed to happen in a civil defense emergency and how, at each step of the way, the public is to be told what to do:

Crisis

Most civil defense scenarios begin with a period of international tension, such as that which would accompany a confrontation in Europe or an oil-producing region between American and Russian armies. In such a period, it is expected that public interest in, and respect for, civil defense would sharply increase. FEMA’s “Guide for Increasing Local Government Civil Defense Readiness During Periods of International Crisis” advises local civil defense officials to meet with managers of their local news media, make speakers available to civic groups, increase the distribution of civil defense literature, and perhaps put out a press release (a sample is provided) saying that “Mayor____of____announced today that some routine steps are being taken to increase the civil defense readiness of the city.…”

Copies of “Protection in the Nuclear Age” have already been distributed to local civil defense officials, and they could decide, if the crisis deepened, to have the film broadcast on local television stations. This is considered preferable to having the film broadcast nationally at the request of the federal government, as such a request could be seen as evidence that the United States was getting ready for nuclear war, a perception that would surely escalate the crisis that had provoked interest in the film in the first place.

Local civil defense officials have also already been provided with a set of 15 camera-ready newspaper articles designed to be printed in a crisis. The articles contain information on warning procedures, radiation and fallout, shelter construction and first aid. Detailed plans for improvised fallout protection are included and, like the film, the articles conclude with a pep talk. The fifteenth article is headlined, “Would Survivors of Nuclear Attack Envy the Dead?…Experts say ‘No’.” It states, “A close look at the facts shows with fair certainty that with reasonable protective measures, the United States could survive nuclear attack and go on to recovery within a relatively few years.”

The articles were distributed in 1981 to more than 5,000 civil defense offices in 50 states. “We estimate,” FEMA has said, “that the emergency information newspaper articles and television films could add survivors amounting to perhaps eight to twelve percent of the U.S. population.”

Evacuation

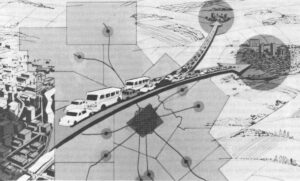

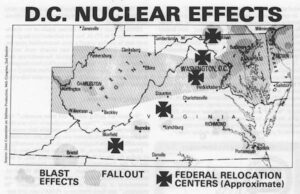

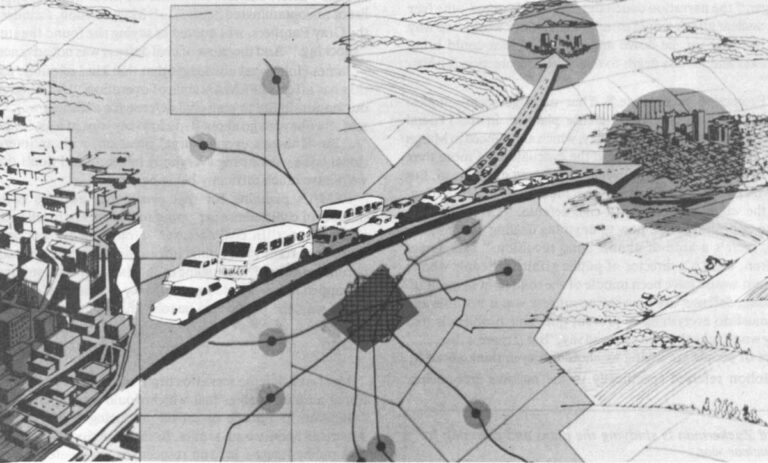

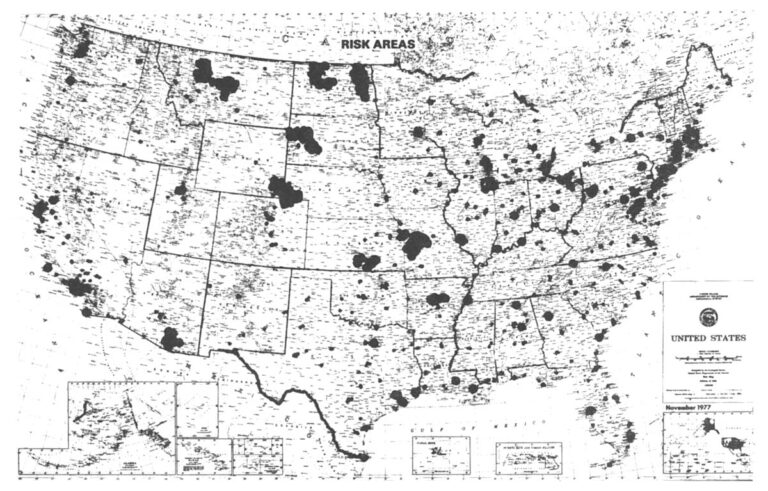

America’s major civil defense program is a slowly-developing plan to evacuate the residents of some 400 “high-risk” areas–major cities and the areas around key military and economic installations–to nearby small towns in an extreme international crisis. If, for example, the American and Russian troops whose face-off led to the stepped-up distribution of civil defense information proceeded to lob tactical nuclear weapons at each other, and American reconnaissance revealed that the Soviet Union had begun to evacuate its cities, then the American President would have the option of ordering a counter-evacuation. If a major nuclear attack on the United States then followed, FEMA asserts, 80 percent of the American population would survive, as opposed to the 40 percent that would survive, according to FEMA, if there were no evacuation.

As of 1981, actual evacuation plans had been drawn up for about 100, mostly smaller, high-risk areas, and those plans included ways of providing evacuation instructions to area residents. Most of the instructions are intended to be distributed during an escalating crisis, but in four risk areas near Air Force bases–Plattsburgh, New York; Limestone, Maine; Austin, Texas; and Marquette, Michigan–FEMA has recently taken out multi-page ads in the phone books. Browsers through the Plattsburgh telephone directory, for example, can now learn that if they live in Plattsburgh south of the Saranac River they are to proceed via Highways 22, 1-87 and, 374 to the town of Dannemora during a crisis evacuation. There they are to report to St. Joseph’s Grade School, where they will be assigned to accommodations in a school, church, or other public building. They will not be allowed to take their pets, the ad in the phone book says, but they are encouraged to bring work clothes, soap, matches, food, tools, toilet paper, credit cards, and their wills.

FEMA recognizes that evacuating cities larger than Plattsburgh (pop. 21,074) will create major logistical problems, and it is thinking about ways to organize such evacuations so that everyone doesn’t simply end up in a hopeless traffic jam waiting for the bombs to drop. A prototype plan for evacuating New York City proposes dividing the population into manageable small groups on the basis of ZIP codes, license plate numbers, and birth dates. Thus, people living in ZIP code 10024 driving cars with license plates beginning AZ or, if car-less, born on the fifteenth day of the month, might be instructed in a radio broadcast to head immediately for the George Washington Bridge, while people in the same ZIP code with licenses beginning AB or born on the twentieth could be instructed to wait twelve hours and then head for the Lincoln Tunnel.

Skeptics have asserted that no major city evacuation is likely to be so orderly, but FEMA is more optimistic. “While no one can guarantee perfect behavior in such an unprecedented situation as crisis relocation, the judgment of those who have studied peacetime and wartime evacuations is that constructive and law-abiding behavior would be predominantly, indeed overwhelmingly, the case,” one FEMA bulletin states.

FEMA has recognized, however, that residents of “host areas” may be somewhat nervous to find themselves suddenly outnumbered by evacuees from a strange city and will need to be kept informed. Sample news releases have been prepared that, among other things, explain crisis relocation and ask host area residents to volunteer to share their homes with evacuees: “The extra bed or even the warmth and comfort of a private home will be deeply appreciated by a family who otherwise will be sleeping in a bedroll on the floor of some public building.”

A pair of final releases has been prepared for the two possible outcomes of the crisis that led to the evacuation:

“The Governor has announced that improvements in diplomatic negotiations has (sic) greatly reduced the possibility of an attack on the United States and that it should be safe for the relocated residents of County to return to their homes….”

“A state of war now exists between the United States and______. Nuclear detonations have been reported in______states and we can expect attacks in our area at any time ….”

Warning

Elaborate plans exist, of course, to inform Americans of an incoming nuclear attack more rapidly than via an after-the-fact press release. The hollowed-out mountain in Colorado where the North American Air Defense Command maintains a constant watch for enemy missiles is also the site of FEMA’s National Warning Center. If an incoming attack is ever detected, an Attack Warning Officer will pick up a party line telephone connected to FEMA offices, 400 other federal agencies and military installations, and more than 1,650 state, city and county warning points (generally located in police and fire headquarters) and announce, “Attention all stations. This is the National Warning Center. Emergency. This is an attack warning. Repeat. This is an attack warning….”

The Attack Warning Officer will then activate another party line linking the Warning Center with national news organizations. At the same time, the President, if he is not too busy racing for the airplane that is supposed to fly him to safety, may activate the Emergency Broadcast System, which enables him to communicate to the nation over radio and television networks.

Meanwhile, the National Weather Service will be passing on the attack warning over its FM Weather Radio system, the Coast Guard will be broadcasting it to ships at sea, and the Federal Aviation Administration will be putting it out over its national teletypewriter network. City and county warning points will be turning on their sirens, if they have them.

Up to this point, FEMA is fairly confident that all will run smoothly. “The weakness in the system,” said one FEMA official, “is getting the warning to the individual.” After all, some people may not be watching television or listening to the radio. They might not live near a siren or know what its signal means. It might be 3 a.m. They might be sleeping.

Ten years ago, the government was considering a warning system that would leave nothing to chance. It was to consist of a network of low-frequency radio transmitters that could cover most of the country with a signal that could automatically turn on sirens, other alarm systems, and even home television sets that had been outfitted with an inexpensive attachment. One prototype transmitter was built in Maryland, but it has since been mothballed and plans for the system scrapped.

What happened, another FEMA official explained, was that the decision whether or not to go ahead with the system was made during the era of Watergate. “After that, there was no way we were going to tell John Q. Public that we were going to put something in his home TV that was controlled by the government.”

Even with the present flawed system, however, FEMA officials believe that word will get out, at least if an attack follows the presumed period of tension. “In an international crisis,” said Joseph Mealy, FEMA’s chief of emergency management system support, “with sabre-rattling, or ground war in Europe, or initial use of tactical nuclear weapons in Europe, the American public would not be too hard to warn. People will be listening to the radio, and, even though the warning system is not designed to wake them in the middle of the night, there’s the old neighborhood door-knocking routine.”

The Shelter Period

Following the initial crisis, the evacuation, the warning, and the attack, everybody is supposed to be in fallout shelters. The shelters will have been constructed by evacuees during the pre-attack days, or improvised hurriedly following detonation. Planners are not relying on however many personal fallout shelters may remain from the early 1960s boom in their construction; emphasis today is on expedient shelters that can be constructed by evacuees during the pre-attack days or improvised hurriedly following detonation. These may consist of nothing more elaborate than the basements of public buildings with dirt piled up against the outer walls. In any case, shelter life is likely to be crowded and uncomfortable and tense. FEMA is doing what it can to make things better.

Following the initial crisis, the evacuation, the warning, and the attack, everybody is supposed to be in fallout shelters. The shelters will have been constructed by evacuees during the pre-attack days, or improvised hurriedly following detonation. Planners are not relying on however many personal fallout shelters may remain from the early 1960s boom in their construction; emphasis today is on expedient shelters that can be constructed by evacuees during the pre-attack days or improvised hurriedly following detonation. These may consist of nothing more elaborate than the basements of public buildings with dirt piled up against the outer walls. In any case, shelter life is likely to be crowded and uncomfortable and tense. FEMA is doing what it can to make things better.

The agency has prepared and distributed a 200-page manual on the proper management of fallout shelters containing instructions on everything from arranging sleeping space (family groups should be positioned between single men and single women) to dealing with the dead (“the Sanitation team attaches some form of identification to the body and removes it to a designated place as far away as possible from the shelter living area”).

In the shelter, as in every other phase of civil defense, the importance of public information is stressed. “Your population will be understandably more anxious and fearful about what is happening to them, and what the future holds after a damaging enemy attack on our nation,” the manual points out. “They will be hungry for official, reliable information. Such information will help control the spread of rumors, reduce anxiety, and make restricted fallout shelter living more bearable.”

Shelter managers are advised to stay tuned to the Emergency Broadcast System and to keep in touch, if possible, with the local government Emergency Operating Center. Local EOC’s are charged with collecting information in their areas and passing it up to state EOC’s, which are to pass it on to regional offices of the federal government or, in some cases, other states. According to the applicable FEMA manual, the kind of message that should be passed directly from one state to another is: “Washington, this is Idaho. NUDET [nuclear detonation] sighting report. Reporting area Idaho 6 reported NUDET to West-North-West at 0400Z, possible Spokane.”

Any information that filters back down the chain, says the shelter management guide, should be passed on to shelter residents in regular morning and late afternoon or evening briefings, as “most people are used to getting the ‘news’ that way.” News summaries should include notice of shelter rules, reports on local radiation levels, and news of the evacuees’ home cities and the nation, the guide says.

As the time to leave the shelter nears, briefings should be expanded to include descriptions of national and local recovery plans. And the guide suggests that discussion groups be formed to brief residents on post-shelter “survival techniques” and to “prepare them positively for the future.”

©1982 Ed Zuckerman

Ed Zuckerman is studying the plans and planning for nuclear war.