(WASHINGTON, D.C.) — Leavings. Fifteen years ago this summer, on a July afternoon, I shook hands with some people I knew well, helped heave a trunk into the back of a station wagon, rode twenty-five miles to a Central of Georgia railway depot, bought a ticket, and went home to Illinois. I was no longer Brother Garret, M.S.Ss.T., student for the missionary priesthood. I was Paul Hendrickson again. I had on that day an $80 starchy black mohair suit, a white shirt, black tie, black shoes, white cotton socks, and a burr haircut. I weighed maybe 135 pounds: most of that was Adam’s apple. As the train pulled off I waved to Father Damian, who had brought me in and now stood on the platform making comic faces. I wish he’d quit, I remember thinking. On the ride home I tried picking up a girl. She thought I was an undertaker.

For all I knew then, my leaving was an isolated act, in tune with really nothing but its own going. I know differently now. If getting in, in the ‘50s, was a complicated collage of personal and cultural forces, getting out, in the ‘60s, was doubly so. The act — ritual, really — of leaving has been playing out in seminaries since Catholic seminaries formally began, 400 years ago. But in the ‘60s, especially the latter half, leaving seemed to take on added mystery, implication. Thousands of men, both seminarians and priests, began leaving — sometimes their rectory or seminary, sometimes their church. Even now the exact number is vague. For a time the boat simply seemed to have overturned, as it was overturning in much of society. It would be well into the next decade and beyond before things appeared to right themselves, though on new terms. The kind of terms that can now, in 1980, allow an influential priest-sociologist named Andrew Greeley to write blithely in his syndicated newspaper column: “The typical American Catholic is reasonably devout but does not accept the Church’s sexual teachings any more.” And for another priest, this one named Connolly, writing in the letters section of Commonweal magazine earlier this year, to say: “…Almost twelve vears ago I became a priest. These have been gestalt years … It has been a winter priesthood — not many happy times — but times filled with life and meaning. It has been a priesthood closed-in, near the hearth….”

In 1967, 40,000 men studied for the priesthood in America; two years ago there were less than 14,000. And yet, in some ways, America seems spiritually hungry. Consider the adulation paid to the pope’s visit a year ago: More than media rage must explain that phenomenon. Minor seminaries are practically an extinct species in this country today, an exotic brontosaur. Two months ago the Capuchin fathers closed 103-year-old St. Fidelis Seminary north of Pittsburgh, victim of dwindling enrollment and rising cost. In 1978 less than 30 seminarians were enrolled in St. Fidelis. In 1976 U.S. News & World Report featured that seminary in an unprophetic article called “Comeback for Seminaries in the U.S.” St. Fidelis, it said, was one seminary that “changes with the times.” The seminarians from St. Fidelis will transfer to a diocesan seminary in Cleveland: Regroup and bunker.

Of course some survive: St. Charles Seminary, in Overbrook, Pennsylvania, stands today in marbled admiration of itself, still readying young men for the archdiocese of Philadelphia. Once St. Charles was claimed to have the longest main corridor of any building in America. It is quite a corridor, polished and draped with heavy oils of bishops and former rectors. The seminary dates from a period when American prelates were putting up churches and schools as if Catholicism were a monopoly board. Edifice complex.

My own seminary closed in 1973. It later became a mental health facility and then a job corps center. I was long gone by then, married, filing for divorce, killing off everything around me that hinted of church and religion. In time I would come back to both my church and religion.

My leaving came at almost exact midpoint of a decade. John Kennedy had been shot, though his brother hadn’t. There had been fire in the Gulf of Tonkin, though not yet on the moon. Watts was a place I had barely heard of. What I had heard of in July 1965 was something called Vatican II. That was the worldwide ecumenical council convened four years earlier by Pope John XXIII. That summer the council was beginning its final session in Rome. When I left the council it had just begun to slap at the seminary walls. Before the council Catholicism was pretty much a sealed capsule. Salvation by rote, detractors have called it. Afterward all bets were off. Almost nothing went unquestioned anymore, not doctrine, not liturgy, not seminaries. In a sense, especially a liberal sense, the council was a revolution scorned: It did not update the church so much as disarray it. At least for a time.

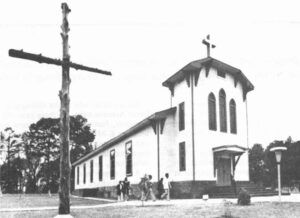

Norman Mailer has written of JFK’s presidency compared to Eisenhower’s as a triumph of the city over the small town. Well, in a way, Vatican II was a move in the church from rural to urban. And it was in that precise time period — after the council had been summoned in 1959, but before it began in 1962 — that my own seminary, a small, obscure place serving a small, obscure American congregation, made a fateful move from the deep rural South of Alabama to the genteel mid-South of Virginia — from firetrap wood to million-dollar brick and steel. I now believe something vital was lost in transition. We couldn’t see it then.

I have since heard a story about one of our seminary teachers, a priest we held in deep awe named Vincent Fitzpatrick, a craggy-faced professor of Latin and Greek. He went one day to the new seminary chapel, stood there alone in amber filtered light beneath the gold dome and the specially commissioned stained glass windows, and said, “Oh, Lord, why are you rejecting our prayers of stone?” But of course even if we had stayed in the deep South — in Mailer’s small town — change and the world would have caught up with us, inevitably. It was only that our move to urbanity made the waiting chaos more glaring, swamping.

In the summer of 1965 I was aware of almost none of these present or future hummings. I knew only that I was going. In bed that morning, waiting for the bell, lulled by muffled snoring up and down the hallway, I tried picturing what the coming days and weeks might be like. The window was open and cool five o’clock light draped itself across my sheets and over to the habit and cincture hanging from a nail on the back of my door. My habit needed rehemming badly, and in several places the heavy black fabric had gone thin and shiny, like an old man’s shin. I hoped I’d always know what it felt like, sliding into the habit, fastening the three buttons at the shoulder as I walked down the hall, holding the belt in my teeth till in one swirl and without losing step I’d gather it around me, hook it at my hip, and whisper my yoke is sweet, 0 Lord, my burden light. I’ve forgotten the rest of the prayer now, though not the feeling.

I had two priorities: I wanted to get enrolled in a school somewhere, finish my degree, and I wanted to kiss a woman passionately on the mouth. I also wanted my gut to stop hurting. A non-decision had yanked up and down inside me for nearly a year, and now I was putting it to rest, or trying to. Three weeks earlier, my stomach rolling, they had sent me in town again to see a specialist in internal medicine. He took x-rays. He tamped, his head clicked sideways. He gave me a jar of chalky green liquid that dried instantly, like miracle paint, on my lips and tongue. “You take all you have to have of this, Brother Garrett,” he said, “but it won’t do a damn bit of good till you make up your mind whether you want to be in that seminary out yonder.” Not long after, I was sent to a mission in Mississippi for a rest. It was there I made up my mind to go. Getting away popped something, released it.

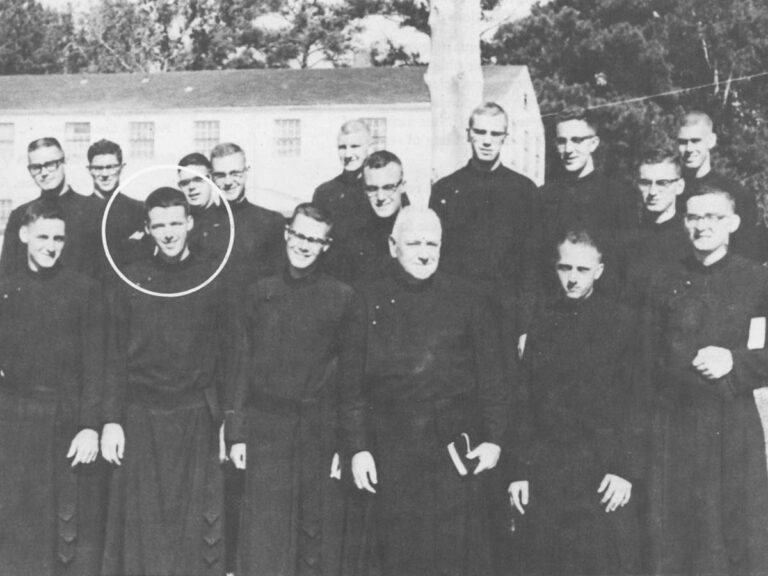

The bell rang — a hammer hitting steel. In seven years I had never gotten used to it. Bodies stirred. Beds creaked. I got up, dressed, went down to the jake to wash and shave, came back, made my bed, put on the habit, went to chapel for morning prayers, a half hour of meditation, mass. Nothing felt very different. I hung my weight between my elbows and knees. You could kneel for hours that way. At the consecration I bowed my head and prayed for worthiness. I was twenty-one years old, a virgin, scared stiff. I had never met a Jew, I had never dated. In six weeks my classmates would be in vows. Where would I be? I went to breakfast and sat in my old seat across from Bertin Glennon. We passed each other food while another novice read aloud from Lives of the Saints. Then I went to my room and began packing.

After lunch I said goodbye to my classmates. They were in colloquy, having their thirty minutes of talk before going back to work and silence. It was the moment I dreaded. I had participated in this ritual dozens of times over the years, but from the other side. Somebody else was always going; I was staying. Not this time. No matter who you were or what face you put on, leaving was funereal and awkward and somehow a little shameful. Nobody quite knew what to say. A trunk on the step was the equivalent of a hearse. Some people managed to light out early, while the rest of us were in chapel or doing morning chores. The priests preferred it that way, I believe. Better on morale. Let’s not start a run on the bank. At noon, in the refectory, there’d be an empty place. “Where’s Wilson?” somebody would say. “He left,” somebody else would say. Nobody ever said for where; just “he left.” They still say it that way. He left.

I shook hands, going around the room, making talk, shrugging. Somebody gave me a two-handed shake. I made a last visit to chapel. A soft September night eleven months earlier my family had watched my investiture in that chapel. Afterward, me wearing my new habit and name, my little brother Mark jumped into my arms. “Garret the carrot,” he said. We had a custom, a rule almost: Anytime you went off the property, or came back, first thing you did was make a visit to chapel. I went in, genuflected. This old wooden building with its yellow windows and smooth dark pews framed our lives. Nothing since has seemed as holy. I slid into the front seat of the car. Father Damian got in, started the engine. Funny, he and I had never really gotten along when he was my novice master. But now I felt an odd affection passing between us. When we turned off the front drive onto the highway, I didn’t look back.

I am trying to do that now. Moving around the country these past few months, talking to men I once studied with, men who are accountants, psychologists, school teachers, rug merchants. I am a little startled at how vividly each of us seems to remember his own moment of departure. It is simply there, like an engraving. In some cases, it amounts almost to epiphany. So in Jackson, Mississippi, Will Booth, FBI agent, sits on the top floor of a pearl-gray federal office building, and says: “I remember it as crystal-clear as if it were this afternoon. It was the first time — well, the only time — I knew in my own mind the Lord was talking to me. I don’t think I made the decision. I was walking on that road in front of the seminary in Winchester. It was evening. I was nervous. I was looking back at the building and thinking about my friends, about what I’d invested so far with my life. And all of a sudden I got as calm … as I’ve ever been. Just something came in my mind and said, “Will, you’re going to leave the seminary and don’t worry, everything’s going to be okay.’ And I remember at that point I began to shake.”

Will Booth was five years ahead of me, in the same class as Richard Ohrt, whom I wrote about last time in this magazine. Ohrt left in June of 1963. Booth, a six-foot-four, syrup-voiced genuinely gentle soul from Vicksburg, Mississippi, left in September, the night before he was to take final vows. He had gone into the eight-day black retreat preceding vows feeling it could go either way — stay or leave. The doubts had grown in him over the previous year. He came in from his walk that night, told his supervisors, packed. The next day, Will Booth was gone. He was twenty-four.

Booth went to Washington, D.C. He went to the executive offices of the Washington Redskins and asked for a tryout. He had been a standout athlete, a natural, and figured, why not. The man was kindly to him, didn’t laugh, sent him over to the University of Maryland. Then he went to Catholic University and talked to a coach about basketball. “Go down there and get some shoes and a jock,” the coach told him, then stood around watching this innocent, earnest young man stuff a ball through a hoop. He got a four-year scholarship. Like that.

Will Booth, married now (to a devout woman raised Presbyterian), with two children, a man who has chased Mafia families in New York and motorcycle gangs in Mississippi, pauses, sucks in a breath, wags his head. “If that’s how you feel when the Lord talks to you. I think, after the fact, that nobody in his right mind, knowing recruiting, would ever think he could walk in someplace and get a college basketball scholarship. But you see, He did it for me.”

In coming months I hope to understand how He helped get us in.

©1980 Paul Hendrickson

Paul Hendrickson is studying the social and religious implications of the collapse of one U.S. Catholic seminary on his fellowship project, “Search for a Seminary: 1955-1980. “