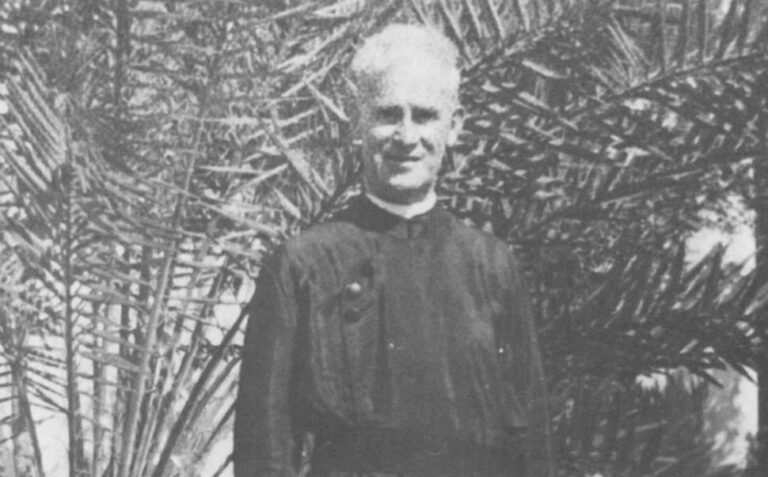

(HOLY TRINITY, AL.) — In the shank of the new century, lean Tom Benson is eagle-beaked, impetuous, sprung from Niagra University. Spectacled, he wears black fedoras. Ascetic, he has a lecher’s grin. A smooth white knob hums in his left ear: He is deaf, or nearly so. He lost his hearing at three, from diphtheria. The fever scorched the nerve. Some days his world is like a great seamless bubble. Some nights he lies in bed dreaming up at the moon. Benson knows this: He won’t go down to Wall Street. He tells a priest at Niagra he is thinking of joining an order. He doesn’t want the Jesuits or Vincentians. He wants a group just starting out, one that will seize his talents. The priest tells him of a man named Judge working down South. This Judge is gathering associates in a spot called Holy Trinity, Alabama. Letters are exchanged. A meeting takes place on one of Judge’s trips north in a Victorian sitting room in a retreat house in Stirling, New Jersey. Benson is led in. Judge is waiting. “I think he must have been studying me right off to see how much I loved God. That’s what he’d ask you: ‘How much do you love God?”’ A month later Benson leaves for Alabama. It is September 1928.

Now Father Joachim is old. His days are glides in dream time, what aboriginal tribes of Australia call the alcheringa. Within six months of the founder’s death, in 1933, Benson was at work on a lyrical book called The Judgements of Father Judge. He wants to get another one done, but it is hard to focus, time is running out. Slack and white he sits beneath a lamp in his room at Holy Trinity. After years as a missionary in Mississippi he has come back here, where he began. His skull looms in the light, gleams. It looks thin as parchment, blue as bird egg. He wears a wildly flowered shirt locked at the collar, beltless polyester pants. The pants don’t fit him any more so he has flipped them double at the waist. The effect is like a truss. A wet cough comes from deep inside. The room is a jumble of books, posters, pennants from Guyana, wadded tissues, vials, folded over issues of Saturday Review and Variety. A passport is on his desk. He is going to Germany for the passion play, he says, though something in his tone already belies it. The other day a doctor told him, “You’re not going to Puerto Rico again!” “I said, ‘Not this week, of course’.” “He … ee”, Father Joachim wheezes, trying to summon the missionary who changed his life that afternoon in New Jersey. But the voice still powers, the mind darts. This voice has a strange, charged quality. Once it crackled from pulpits and into radio microphones. Father Joachim’s veined right hand flutters for the arm of a chair. He puts a finger aside his nose and smiles — as if he is going to say abracadabra and vanish to a room where Tom Judge waits, at prayer.

Father Judge could take whatever you were talking about and transfer it back to the spiritual. That’s why I couldn’t understand him in the beginning. I wrote him a long letter asking what I could do down here as a Missionary Servant. He wrote back: “You will study the wounds of Christ. The Word made flesh.” That meant nothing to me. I had a degree. I was a college graduate. He wrote another letter and said, “The Holy Ghost is busy with you. Why not yield to His sweet impulses?”

His conversation was always in heaven. He was riding horseback in Puerto Rico. “I’m thinking of the Blessed Mother,” he said aloud. “She had these riding experiences. Over the hills of Judea.” He’d get up in the morning, first thing he’d say, “Benedicamus Domino.” We were supposed to answer, “Deo gratias.” I couldn’t understand it, getting up in the middle of the night, blessing the Lord for the privilege. He worked many nights late. I had a room down here, he had a room over there, they’re torn down now. He’d say, “Good night, brother, I’ll call you in the morning.” And he’d call me in the morning, all right. He’d get me up at four o’clock. He was charmed by those morning hours, subdued, solemn. He had this kerosene lantern and he’d carry it along the walk with him to chapel, a watchman in the night. He’d put the lamp on the choir rail. A faint glow would reach down into the pews where we sat, huddled against the cold. I considered it very mysterious. It might have been happening in the Catacombs.

He’d come home from a trip and I’d carry his bags to his room. “Peace be to this house,” he’d say. “Peace be at this house,” he’d say again, louder. Then he’d turn around. “Say something, Brother!” You see, he was so deeply spiritual he thought other people were that way, too. With him you’d say prayers when you passed a cemetery, prayers when you were getting into a car, prayers when you got out of the car, the rosary on a train, the rosary in the car. You never knew when the rosary was going to stop but you knew when it was going to start. You’d better be ready.

I remember the first time we drove over to the retreat house. We called it the other side. I was driving. Often I would drive him. Sometimes I took a long time to go a short distance because I knew he was teaching me. Father Judge had this way of getting to you, tutoring you. I was very much careered by him, although I didn’t know it then. We’d just turned off the main road when he said without warning, “Out of the depths I have cried unto Thee, 0 Lord.” I glanced at him. I didn’t know whether he was sick, or what. He was staring straight ahead. I had to say something. “0 Lord, hear my voice.” “Let your ears be attentive to the voice of my supplication!” he said. I thought maybe if I drove a little faster that would take his mind off of it. I had never heard the De Profundis before. I didn’t know it was a prayer. If you and I were driving to the other side we wouldn’t suddenly start saying the De Profundis. He bewildered me. It took me a long time to figure him out. And by then he was dead.

He couldn’t drive a car. I never saw him drive a car. But he was always telling me how to drive a car. One day we were coming down from Gadsden after a funeral. The roads were a terrible dust. He said, “I command you to drive this car thirty miles an hour, not twenty-nine, not thirty-one.” We got to Phenix City. I got out. “Here, you take it,” I said. He said, “Get back in here!” He hated self-will. Once he gave me a homily on how to eat a pork chop. We were having dinner. He got up from the table and came down to my plate. “That’s not the way to cut a pork chop.” “Well, what way do you cut a pork chop?” I said. There was no special way but to him there was.

He despised selfishness, somebody ungenerous with himself. He’d step on pride every chance he got. We were constantly in conflict. Like St. Paul I saw through the glass darkly as one who did not believe. I persecuted him. He had very little pity on me. He’d cut me down to size. He’d say, “You’re Christopher Columbus, aren’t you? You think you’ve just discovered us. You think you know it all. You think we’ve got nothing better to do but listen to your fiddle-faddle.” He had the impatience of a saint. He was like a prism flashing eloquence. He felt he was meek, miserable forever making mistakes. He was always on his knees. He didn’t have degrees. He had simplicity.

He loved the farm. He loved taking a walk to the farm. He loved nature. He was a child of nature. He loved every atom and every star. We always had chickens here. They drove me crazy. He was always planning ways to make money from chickens laying eggs. He had no mercy on a white leghorn that didn’t produce dozens of eggs. Chickens also had to do the will of God, and they must be made to know it. We had a mule. That mule was the only one of us who could look him in the eye and get away with it. He had absolutely no influence on that mule. He actually pampered it. He loved sweet potatoes. He could tell you stories on sweet potatoes. He loved to eat. He loved good food.

He would take anybody down here and allow him to do what little bit he could. I wrote to him once in the North. I was in charge down here. I said, “Don’t send any more people here. We can’t take care of them, we don’t have the money to feed them.” He writes back: “Don’t forget whom He might send. Don’t forget: Whoever comes we must live up to his expectations of perfection.” He could turn the tables on you like that.

In December 1932 Judge and his struggling band are attacked on the front page of Baltimore’s archdiocesan newspaper by Archbishop Curley. The attack is over the order’s attempted sale of bonds to keep itself afloat. “We have no jurisdiction over Father Judge,” says the archbishop in an open letter, marked OFFICIAL, to the people of his diocese. “We are not questioning his sincerity. We are sure he has ‘visions’ of being able to meet his obligations. However, we do not want to see our people banking on visions.”

A copy of that paper was put in every mailbox of every religious house at Catholic University. Imagine us walking into class after that. Curley thought he was right. And that all helped eventually. But at the time it didn’t help. I was furious. I asked Father Judge what we were going to do. I wanted to sit down and write Curley and tell him to go to hell about forty times. Father said, no, we haven’t time for that. It got so bad… that was one of the reasons we had to leave Catholic University. Nobody would teach us. Nobody would take us in. Everything stopped. We had friends among the Carmelites. I went to see the superior of the Carmelite house on the feast of Saint Theresa, the Little Flower. I took him a rose. I swear to this. Stupid, I’m very stupid. But it all worked out. I know so much of this history that the others never knew that I have been accused of making it up. I kept saying, “I don’t have the brains to make up things like that.” They didn’t believe it. Now they believe it. There was too much Divine guidance in his work, there were too many people who tried to stop him. I don’t know why he came to me in a flash after he died. I think he must have had a special illumination.

Eight months before Judge’s death, Benson commits a disobedience. Actually the matter is small. But Judge is furious. “You have been disobedient”, he tells Brother Joachim over the phone. “You go home until you learn to be obedient!” Benson, his back up, goes home to Albany.

I never saw him again. Once, four guys and myself — I know who they were, they’re all dead now — drove to Providence Hospital to see him. He was dying. Somebody got the bright idea I might upset him. They all went up and I sat in the car and wept. Got very despondent but said nothing. I never saw him after March 23, 1933. Things were so upset at that time. He had no one he could trust, no one to turn to. I went to see his nurse after he died. I made her tell me everything he said in those last few hours. That’s when he whispered, “The chalices are flashing in Rome.”

©1980 Paul Hendrickson

Paul Hendrickson is studying the social and religious implications of the collapse of one U.S. Catholic seminary on his fellowship project, “Search for a Seminary: 1955-1980.”