(WASHINGTON, D.C.) — They are older, bulkier now, though much else about them seems remarkably the same. We are what we were, but not quite. Sometimes it almost seems like a dream. There were maybe 120 of us spread over four years of high school and two years of college. We came from Catholic grammar schools in places like Bayonne and Dubuque. We were altar boys, daily communicants. We belonged to the only “the” Church, as Lenny Bruce once said. We wanted, all of us, to be priests. Some of us made it.

He has seen men wrap other men’s testicles in live phone wire, then sit back with a smoke and a Victoria Falls beer waiting for a call to come in. “It’s more effective if you make the guy sit in a tray of water,” he says. A jolt like that won’t kill you, just snap your head around like it’s on a pivot. After that the prisoner usually talked. He wouldn’t participate in such interrogations, he says. He had other ways, psychological means of getting information. An airy smile I remember from someplace deep inside me scissors sideways on his mouth. Once this smile and its owner ragged me after I muffed a pop fly in an intramural softball game. In his fingers is an unlit cigarette. He is sitting on the edge of the sofa, his pale blue eyes inert, placid. He holds the cigarette like a tiny baton, then tamps it smoothly against his thumbnail. “Course, there have been times when I thought a VC was lying to me I haven’t been too nice.”

On the other side of the sliding glass, in fierce Arizona light, his three-year-old daughter, Justina, plays on her new swing set from K-Mart. She is just up from a nap. Her peals bounce against the glass, harmless mortars. “Hiya, Piggypoo,” her father says, mugging.

Apocalypse then, paradox now. His name is Richard Ohrt and once we were both in a Catholic seminary. Even back then, over two decades ago, as we went to chapel eight times on a normal day, as we walked silently in lines to the refectory, fretting about homework and our vocation — whether we really had one, and what would happen if we lost it — there seemed something two-tracked about him, more than there does about most of our lives. Not that I could articulate this. I was a wretched freshman, all squeak and bone, from a town in Illinois no one had ever heard of. Dick Ohrt was in his second year of college, five years senior. He wore a cassock and lived in a room on the other side of chapel. I wore high-water pants and slept in a dorm with 80 other boys, in metal bunks with bad springs. If I wanted a shower, I went to the end of the building and stood in a cement-block room with nozzles coming out of the wall.

He had status, I had zits: Our lives passed at an opposite angle. He was going on to the novitiate and to the major seminary to read Kant and the Summa Theologica. I was trying to get down Latin declensions and figure out the odd, dirgeful joys of Gregorian chant. Fate put me on his waiter crew, his softball team. If you hurt too much, if you could show him a need, he’d pick you up, stroke you. That was the other part of him: He had a soft spot for underdogs, the downbeaten, even if he were the beater. He was like a prism flashing contradiction, as we all are, only his flashes seemed luminous. At least to me.

His nickname and ancestry were the same: Prussian. (Some called him Lugerhead and lived to tell.) Though he secretly loved the name, reveled in it, gloated that God or fate or just blind stupid luck had turned him out Germanic “while the rest of you slobs mucked along as best you could,” you didn’t dare call him that to his face. Not if you were younger. He’d cut your fingers off at the knuckle, or make you think he would.

After 1959 I never saw him again. But I didn’t forget him. Years later I could picture that popped-up chest, that patented torpedo drive down enemy throats on the basketball court. He played guard and had a way of tucking his legs up under him, like a contortionist. You’d see a blond blur and black tennis shoes. Once, in a game against Open Door Community Center, the drive backfired and he ended up on the floor with part of his front teeth sitting beside him. The next time we played that team, he went in feet first on the little guy who had tripped him. He came up grinning. “I got that sucker,” the grin said. “You get in the way, you chew rubber,” is the way he explained it to me the next week on waiter duty.

“Yes, I’d say he was religious,” says a classmate of Ohrt’s I recently called up. The classmate is an FBI agent in Atlanta now. “In the sense that whatever you do, you have to do it to perfection. If it was time to meditate, nobody could meditate like Dick.” We meditated every day at 6 a.m. in chapel. If you fell asleep in that half hour, a prefect would come up behind to poke you. This was usually good for a gig. Three gigs and you spent Saturday with a swingblade in a field below the gym we called the swamp. My sophomore year I practically lived at the swamp. I never saw Ohrt down there.

He is seated in his living room in Tucson. Art pieces he and his wife have picked up from Greece, Spain, other places in their military travels festoon the room. He is forty, about to turn forty-one. The body is lean, trim, muscular, the face the same blond wedge of smoothness. His hair is longer, combed flat to the top of his ears. When I knew him it stuck up like a brush. The day before he had come down the walk at my motel, in shades, back of his hand up to rap at the door. I knew him instantly. Two weeks earlier, on the phone, when I asked if I could come out, he said: “Have at it.”

We are back from a hike in the desert, where he has been pointing out varieties of cactus. He was gentle in his affection for the desert, his knowledge of it. “You should see the seeds of these saguaro,” he said. “Talk about the parable of the mustard seed.” His dog Licorice a dachshund, snores in his lap. Last year, Licorice had a runny eye. Her owner nursed her back, put the salve in.

Nam:

At night they’d go out on free fires. Fireflies, they called them. They’d run them from maybe eleven o’clock till 3 a.m. The air felt soft then, clean, like early mornings in the seminary when you were sacristan and had to be the first one up to get the chapel lit, the vestments ready. He’d be in the command copter with his maps and surveillance experts and Vietnamese bodyguards. He’d have a .45 on his belt and two canteens — one of water, the other of cognac, so in case this time was the last time he could go out in a swill of glory. Up ahead would be the light ship and beside him the cobras: two-man choppers with 20mm cannons on their noses. It was beautiful, the way those snakes could roll in, blades beating air, thunking, scything at the night. There weren’t supposed to be firiendlies down there, and if there were, t.s. Bombs away, dream babies. He says this almost trancelike, his arm rising and then curving toward the coffee table and some far green icon.

Once or twice a month the chaplain would copter in to say mass. He would use Ohrt’s quarters. Ohrt would be the acolyte.

Another icon, farther back: a 3×5 black and white photograph with ragged edges, the kind you got from drugstores in the fifties. A boy is seated on the ground behind a portly friar. The boy is fair and skinny — his knees are hunched up under his chin. An old ball cap, with a long bill, is pulled low. This moment was frozen during a “sem week” the summer of Dick Ohrt’s seventh grade year, 1952. They held it at a Benedictine monastery in St. Mary’s, Missouri. The idea was to try on for a few days the life of a Catholic priest, or at least of a seminarian, see if it fit. Back then, before Vatican II, before the next decade would turn everything, including the Church, around, it was still conventional wisdom to pick a vocation ripe — before “the habits of vice take possession of the whole man.” That’s from the Council of Trent, 1563. Dick Ohrt didn’t need much picking. Seminaries were where the best and brightest Catholic grammar school boys aimed, nudged on by nuns and the parish priest and in most cases their folks. I had a sem week, too. Mine was in Technie, Illinois, at the Divine Word Fathers. Only my pictures were gone.

The life of a seminarian — its prayer, its study, its rituals, its camaraderies — mysteriously appealed. The next year Dick Ohrt went away for real to a place called Holy Trinity, Alabama. To this day he can’t exactly say what made him go into a seminary, or even what made him come out. “Grace,” he says, letting it cut both ways.

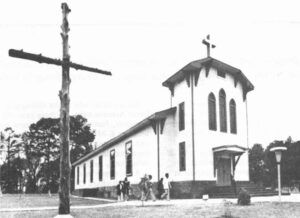

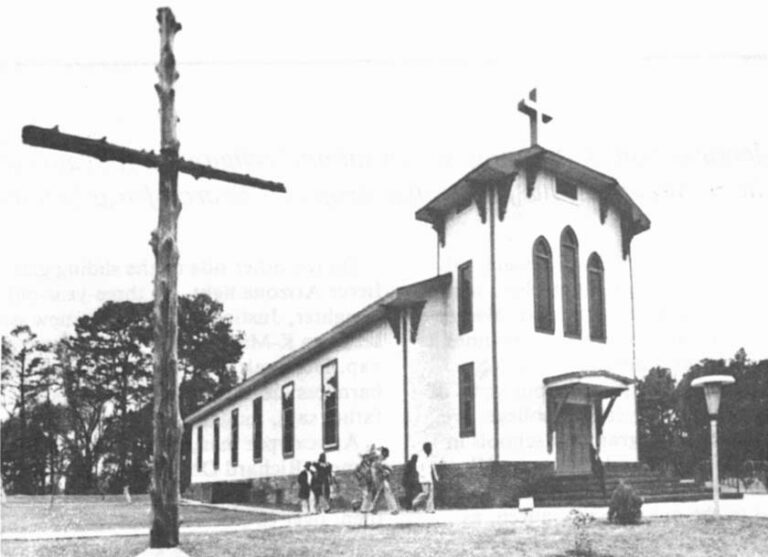

The rural deep South was an unlikely spot for a 14-year-old to take up studies for the Catholic priesthood. Holy Trinity had been an old plantation till the twenties. It stood twenty-three miles out from Phenix City, along the Chattahoochee River, past a rise in the road called Red Level. Russell County, Alabama, had red clay, sweet pine, kudzu, and Baptists. DeSoto passed through in 1540 with 12 priests and four friars; it may have been the last time Catholics were chronicled. In 1957, the year before I came, the Klu Klux Klan burned a cross on the lawn. My freshman year a reporter came out from town, looked around, and wrote: “Spread out to the horizons are lush, green patches of spring wheat and oats and fat cattle grazing and tractors plowing in the black loam, for these are men and women of the soil as well as the spirit.” Actually, the loam was pretty sandy. But you knew what he meant. Maybe 500 of us went through the place during the forties and fifties; maybe five percent are priests today.

But Holy Trinity is a kind of Nazareth to take with us even if we don’t believe in Nazareths anymore. Holy Trinity itself doesn’t exist anymore, not as a seminary. The old wooden gym, a converted roller rink that had been brought over in 1949 from Ft. Benning, Georgia, still stands, wheezing against time. They’ve put a cry room in the chapel.

Dick Ohrt stayed in the seminary ten years. He quit three years before ordination. By then he had a religious name, Brother Meredith, and a black gown called a habit. Once you were invested in the habit (you “received” it after six years and a period called postulancy), you wore it nearly everywhere. It was both badge and wonder of convenience. We used to kid that the habit hides a multitude of sins. We weren’t just talking of wrinkled wash pants and T-shirts with yellow holes.

Then one June evening, 1963, he boarded a train, changed the next day in Chicago — where he also changed from a black mohair suit to a new sharkskin green one he found in a cheap store in the Loop — and rode home to Davenport, Iowa. He got in about 3:30. He took a cab out to 2307 College Avenue, past Sacred Heart Cathedral Parish, where he had served 5:30 a.m. mass in grade school. His dad was home from his job at John Deere across the river in Moline. His mom was setting out supper. He walked in the back screened door. “Welcome home,” they said. “Sit down, son. We’ve a place for you.” Dick Ohrt was 24. He had just been dispensed from vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. He had dropped back into the world like a new calf drops from its mother. A couple of years later, I would have my own drop. The incidentals change some, but the substance is the same.

“Where else was I going to go?” he says. “I had $200 they gave me, some of which I’d blown on the suit. I didn’t know anybody. I figured I’d better go home and get it screwed up, tightened up, bolted down. “

He did. Nine weeks later Dick Ohrt was in the army, on track again. He went away, at night, with one suitcase; it was not unlike going off to a seminary. “These people would get up at — what? — 6 o’clock in the morning? Hey, that wasn’t hard. Scrubbing down the latrines? Hell, I’d already done it.”

In his “stress” interview for military intelligence school, the officer had looked over his personal history statement. “He said, ‘Mmmm, I see you were in the seminary. What are you, some sort of fag’? I said right back, ‘Well, sir, probably not any more than some people in the army.”’ He passed. In his intelligence class at Ft. Holabird in Baltimore, 14 of the 27 were former clergy students. It was no coincidence. Former seminarians make great security clearances. They know right where you were all those years.

By 1967, Dick Ohrt was living in a tinroof hootch with screening halfway down the walls in a place called Phuoc Tuy Province, Vietnam: A different sort of mission land. He ended up doing two tours in Phuoc Tuy, the second a volunteer tour. When he came back the second time, the villagers had a plaque waiting for him. Four years had passed. His first marriage was fraying. He was in the general mess his first night when a gate guard stuck his head in, said hey, there are some Vietnames outside to see Dai’Uy Ohrt. Dai’Uy means captain. He went out. A dozen of his old operatives and informants were there. They took him to a restaurant, where the eating and toasting went on for hours. Then they gave him the plaque. It is a painting of a wild stallion. In the upper left corner are four Vietnamese characters. They mean: A Horse Returns a Second Time to its Place of Victory. The plaque is on a shelf in the Ohrt family room now. He almost pitched it, his wife says.

“I don’t know,” Dick Ohrt says carefully, evenly, trying to get this right, “maybe I was extending to those people what I had wanted to be as a Missionary Servant.”

Dick Ohrt was passed over for promotion to major last summer. He had served in army intelligence sixteen years, involved in counter-espionage, surveillance, special investigations. He spent the last couple of years in Germany, and that’s where he was in August when the letter came. He left the army February 1 of this year. So far he hasn’t found anything. A while ago a guy called up and offered him a security investigation job: $3.95 an hour, seventeen cents a mile for the use of his own car. Ohrt laughed. Then stuck the phone down. “I’ll snap back,” he promises, as we say grace.

©1980 Paul Hendrickson

Paul Hendrickson is studying the social and religious implications of the collapse of one U.S. Catholic seminary on his fellowship project, “Search for a Seminary. 1955-1980.”