(LOS ANGELES) – “More important than even the directors and producers, the writer is crucial to the success of black television shows,” says Cleavon Little. (Mr. Little, who starred in the Broadway hit “Purlie”, was also a featured performer in the film “Blazing Saddles” as well as television sitcoms such as ABC’s “Temperatures Rising.”) “Usually when stories are bad, black stories on television, it’s because you have white writers who are attempting to write about something they haven’t experienced. Now I’m not against white writers, if a writer’s good he should work. Still, most writers usually write out of their own experience, that’s when they’re best. But not with black shows. Here you have white writers trying to imagine experiences they can’t conceivably know about… If a writer is writing out of his own experience and I, as an actor, am working with the material, I can act, move my body, get into the emotional feel of an authentic situation.

“The biggest problem I’ve had in acting is having to say things written for black characters by whites that could never have come out of that character’s experience. It can be as simple as the difference between a character saying, ‘I think that you should sit in that chair,’ and, ‘you oughta sit down.’ But it’s awful, and finally hurts the show because if the actor can’t believe it the audience certainly can’t… There is a different set of timing for how blacks should work comically, and most whites are simply unaware of it. If you look at Jewish comedy, it comes from Jewish writers and it comes from an authentic level. It’s funny because it’s consistent from the bottom up. But black comics in television are saddled with a bunch of white writers who don’t know how to write for their timing; consequently, many black sitcoms are literally without substance. The problem for television comedy about blacks is simple-white writers got to give it up!”

As an actor, Cleavon Little’s concern over the behind-the-scenes business of writing for television is perhaps rare. The problem he addresses, however, is of enormous import in analyzing the black comic image on television and, maybe, even in determining the future direction of black comedy in the mass media.

During the past three decades, as television has expanded to a point where its images reach nearly every American home, live variety shows out of the vaudeville mold have become more and more rare. Those shows were once the spawning ground for fresh show-business talent, both black and white, and their virtual disappearance has critically altered the traditional path that performers followed to learn their trade. As dancer Honi Coles remarked: “That’s the tragedy of show business today; the kids have no place to learn, expand and become involved in the whole thing.”

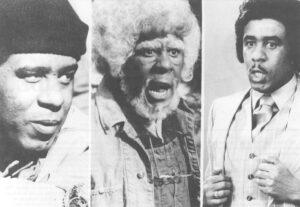

For black entertainers, particularly comedians, the consequences are particularly dire, since the live stage shows, performed before primarily black audiences, were practically the only places where blacks could try out and refine comedy routines that relied solely on the black comic tradition. Comedians from Dusty Fletcher and Pigmeat Markham to Flip Wilson and Richard Pryor initially established their comic styles working live before black audiences. Their routines and jokes, for the most part, were written and developed for and depended upon a tacit understanding of the underlying assumptions and attitudes of the largely homogeneous black audience before whom they performed.

The result was humor that was thoroughly black in conception, attitude and tone.

The emergence and domination of television as the entertainment medium has completely altered this situation.

Matt Robinson-a black writer and producer whose credits include the films “Save the Children” and “Amazing Grace” (which featured Moms Mabley, Butterfly McQueen and Stepin Fetchit), as well as television scripts for shows such as “The Waltons,” “Sanford and Son,” and “Eight Is Enough”- explains the impact of television this way:

“All comedy on television is basically Jewish comedy. It’s Jewish because Jews were dominant in the field early on; they were on the ground floor when television emerged. Therefore they used the style of the borscht belt, stand-up comics who used that rapid-fire approach- setup-setup-punch line. The style was adopted because it solved the technical problem of television’s having to get everything in quickly. Television is a fast medium, and that requires a certain kind of approach. You have to grab the audience immediately, within the first 30 seconds or so, or else they change the channel.

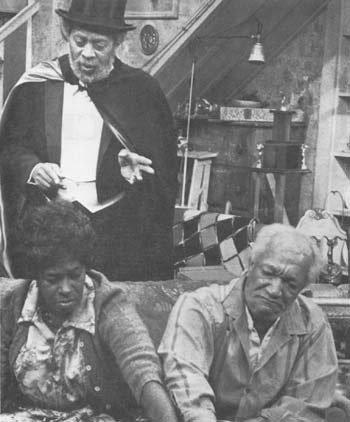

“What we might call black humor on television is now very similar to Jewish humor. Television reaches a mass audience, which of course includes blacks, and they are as vulnerable to mass media techniques as anyone else. To a certain extent blacks have come to expect the same approach. In a show like ‘Sanford and Son,’ for instance, the tone of the humor was black, the nature of the material was black oriented, but the structure followed the same formula as any other television show. It’s based on the unlikely proposition, as we all know, that there is always someone standing around with witty, flippant responses to anything that’s said. And that’s not a black development…

“I think black humor stopped being a dominant force with the advent of television. Black humor, to me, is that stage show type humor that flowed from specific character types and situations that were familiar to other blacks-almost exclusively so. It wasn’t dependent on rapid-fire joke telling. Pigmeat Markham, for instance, did that bit that dealt with a woman who comes into the courtroom and accuses a man of ‘messin’ with her digits.’ Now it was never explained what digits were, but the moment she mentioned it Pigmeat became outraged and yelled, ‘He was! ‘ The audience went crazy. Not because it was funny in the setup- setup- punch line manner, but because of Pigmeat’s attitude. I mean, nobody even knew what digits were, that could’ve meant anything: money, the numbers or policy game; it even had sexual overtones. Still, it was hilarious. That kind of comedy, what I call black humor, is not used on television.”

Many white television writers agree with Matt Robinson’s appraisal of black humor on TV having a distinctively Jewish cast. According to Adrian Spies, a freelance writer who usually writes drama: “Black television is largely in the hands of Jews, well-intentioned Jews, mind you. But we know that self-hatred is endemic to minorities, and I think some of what we’re seeing is a kind of second-generation self-hatred; empathized self-hatred.” And some, like Dick Baer, who has written scripts for black sitcoms such a “What’s Happening” and who now writes for “Archie Bunker’s Place,” are even more damning in their appraisal of the situation. “Comedy dealing with racial matters,” he says, “has to do with what people expect blacks to do. To a certain extent, it’s what blacks expect blacks to do. But since whites are in the majority they make the decisions about how blacks are going to figure into the entertainment industry… They are working both sides of the streets. They are selling non-servile blacks to placate the black audience and, at the same time, showing stupid or amoral blacks or unrealistic blacks to satisfy the white audience’s assumptions about blacks.”

Nearly everyone I’ve talked to agrees that black television sitcoms and even black variety specials where comedy is featured are at best diluted or “whitewashed” examples of authentic black humor. When the remedy that Cleavon Little has suggested-more black writers-is brought up, however, there is strident disagreement. The majority of black writers feel that they are being discriminated against; members of the Writers’ Guild have formed the Black Writers’ Committee to address that problem. Most white producers and writers seem to feel that there are simply few good black comedy writers.

Thom Mount, a Universal Pictures executive who has produced Richard Pryor films such as “Which Way Is Up?” for example, states flatly that “most of the black writers aren’t very good.” And Dick Baer, while admitting that the television image of blacks is often distorted and that there are few “good black shows that have ever been on television,” still feels that “knowledge of black dialect is not sufficient to pretend you’re an expert on black scripts. Black comedy writers who don’t write good jokes-when they’re working on shows as editors- shift the language, they claim, into the way blacks talk, as if it gives them a special edge. But not everyone talks that way. I find it annoying and not important to comedy.”

The real problem, however, may reside in the conflict between black humor and the formalized comedy approach that dominates most television writing. Bob Peete, a black writer who worked on “The Bill Cosby Show” and was story editor for “Good Times” for several years, expressed it this way: “There is a real difference between black humor and white humor. The chief distinction is that black humor is more attitudinal; it’s not what one says, but how one says it. An example is, say, if Redd Foxx is on camera and someone knocks on the door. Redd might say, ‘Come in,’ and the audience would crack up. Now ‘come in’ is obviously not a joke. The attitude he imparts to the line gets the laugh. Richard Pryor does the same thing; he doesn’t tell jokes. White humor is structured to a straight-line, punch-line format. And television has become a medium of one-liners. One of the problems for a lot of black writers-at least in the scripts I read while working with ‘Good Times’- was that they could not effectively write one-liners. They could write lines that, in their heads, they could imagine the performer delivering with a certain attitude. But on paper it doesn’t translate, especially to somebody white who is expecting the one-liners. They simply don’t see the humor. Then the white producer will say, ‘Well, this guy isn’t funny. He can’t write.’ What they’re talking about is that the black writer is not writing what they are used to reading. It’s not their conception of humor.”

As distressed as many black writers and entertainers are about the present lack of authentic black humor on television, most expressed more concern over another trend in television programming: that is, the gradual diminishing of the number of black oriented shows appearing at all. With “The Lazarus Syndrome” and “Paris” in ratings trouble and likely to be shelved, the only regularly scheduled, black oriented shows that appear likely to survive the current season are “Different Strokes,” “Benson,” and “The Jeffersons.” Many black writers and performers feel that this sparse representation of black shows clearly reflects the current disinterest in black entertainment by network executives.

The most frequent response to this type of criticism is that black shows are simply not doing well in the ratings. And considering that, as Bob Peete put it, “the industry is one percent show and ninety-nine percent business,” such an explanation seems reasonable. Many writers, black and white, however, feel that dwindling black representation on television has a more cryptic and complicated cause.

Alan Manning, a white producer-writer who began writing for television in the early fifties and worked for comedians such as Imogene Coca and Jackie Gleason, as well as producing the Norman Lear inspired “Good Times” for four years, says, “I think the black thing may have peaked on television. We may have exorcised our guilt about blacks with ‘Roots.’ I think the feeling is that there is little left to say or do about the racial thing.”

Some black writers, experiencing an employment crisis because of the lack of new black shows, feel that the cause resides with the low quality of many black shows. “The shows don’t last because they’re so poorly done,” says one writer. “There aren’t enough black writers working on them, and the white writers really don’t know enough about black life. It’s a self-fulfilling type situation-white writers produce mediocre shows about blacks and, when they fail, decide that the audience doesn’t want to see black shows. It’s dishonest and hypocritical.” With regard to comedy, Cleavon Little remarks: “How can you have black comics working with white writers who write jokes for Donny and Marie Osmond? It just doesn’t make sense and, finally, it’s bound to fail.”

Whatever the causes, it is apparent that in terms of authentic black humor, television is a virtual wasteland. The style of humor presented on black sitcoms has very little to do with the comedy traditions of black Americans. And authentic black comedians, such as Richard Pryor, who have refused to mold their humor in the television style, have proven inimicable to the home screen. The consequence is that a rich tradition of American humor is being almost totally ignored by America’s most powerful and influential medium. And the question raised is, with this neglect, what happens to black humor in the future?

Cleavon Little has a suggestion that may provide the answer. “We don’t know how black comedy might develop on television because we really haven’t explored the possibilities. I’ve been doing pilots for shows for years and they’ve failed, I think, because they’ve all had white writers, white producers and white directors. We need blacks doing those things to bring another kind of ethos, nuance, to the comedy. That hasn’t been investigated. Let us try it, control our own humor, and I’m sure you’d see a difference. I think the audience would buy it.”

©1979 Mel Watkins

MEL WATKINS is currently interviewing and. writing from Los Angeles for his APF project on Black Humor from Stepin Fetchit to Richard Pryor.