LOS ANGELES – Fifty years ago Lincoln Theodore Monroe Andrew Perry, a.k.a. Stepin Fetchit, reigned as the first and only black movie star. He had made his motion picture debut in the silent film “In Old Kentucky” (1927) playing opposite Carolynne Snowden; it was a groundbreaking role in which for the first time in a Hollywood film “a clear love affair -a sexual relationship” was depicted between blacks (Slow Fade to Black, Thomas Cripps, Oxford Press, 1977). His real success, however, began in one of the early talkies, “Hearts in Dixie” (1929), where he introduced the dawdling, slow talking, illiterate character that had been created years ago by others on the vaudeville circuit, but would become his trademark.

According to his sister, Marie Carter, a hundred or more actors had tried out for the part. “[Step] said he just stood there looking like he didn’t know where he was or why he was there and he was scratching his head, which he had shaved clean, and just looking around like he was lost. I guess he looked so lost and everything that he got their attention.” When one of the directors called him, “he looked around the place, acting like they couldn’t have been talking to him, but knowing all the time that they were.” Finally, “he turned around all slow and wide-eyed and pointed to himself – you know how he does that – and said, ‘Is you talkin’ to me?’ And the dumber he acted the more they laughed, because nobody had ever seen anybody that dumb and ignorant.”

During the next decade, Stepin Fetchit appeared in 26 films and earned somewhere between $1 and $3-million. At the height of his career, as was the custom in Hollywood at the time, he flaunted his wealth outrageously. He is said to have had a fleet of limousines, his real pride being a pink Cadillac with his name emblazoned in neon on the side. He boasted about the retinue of 16 Chinese servants he employed and, like such black athletes as Joe Louis and Muhammad Ali, he was constantly surrounded by an entourage of hangers-on and celebrity groupies. It was a spectacle worthy of a Busby Berkeley extravaganza. And it seemed even more prodigal when one considered that Step was a black vaudeville hoofer-turned-comedian who had made his fortune portraying the lazy, no-account Negro that, in the American psyche, justified blacks’ low social status and income. Step played it to the hilt.

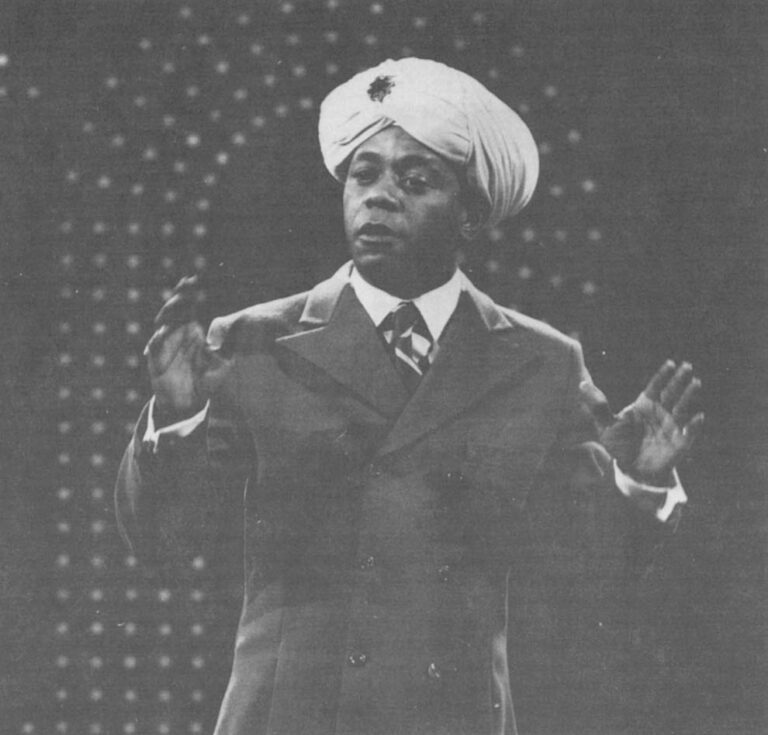

A typical bit in his stage routine went something like this: “I’m so lazy, even when I walk in my sleep I used to hitchhike. My head was so bald I used to comb it with a spoon. People say, uh, how’d you get in pictures? I say, well… when I was a kid I always wanted to be somethin’, ‘course I didn’t want to do nothin’ to be it. I used to go ’round trying to get a job doing nothin’, but everywhere I went they either wanted you to do somethin’ or else they didn’t wantta give you nothin’ for it. So I kept trying ’til I growed up, then I seen this man in California making a picture. And I say mister you want somebody to do nothin’, and they say, ‘Yeah!’ So I been busy working ever since. Yeah, and I work up to the place where the less I have to do, the mo’ I make. Tryin’ to make as much as I can, so when I get old I can rest.”

Now 78 years old, Stepin Fetchit resides at The Motion Picture Country House and Hospital north of Malibu in California. Most of his fortune was dissipated on his lavish life style and, in 1944, $3-million in debt and nearly penniless, he declared bankruptcy. In 1976 he survived a stroke, but it paralyzed the right side of his body and left him with aphasia. (Some of his friends and family contend that stroke occurred while he was reading one of the typically vitriolic magazine articles that began appearing in early 1960’s and which characterized him as the primary culprit in fostering the negative image of the lazy, shiftless black. At one point, Stepin Fetchit filed a suit against CBS because of an “Of Black America” episode hosted by Bill Cosby in which he was called, “The white man’s Negro, the traditional lazy, stupid, craps-shooting, chicken-stealing idiot.” He lost the suit.) Although he moves with obvious pain now and his speech is severely impaired, there is a glint in his eyes that belies the image of the doltish character he established on the screen and stage. As he struggles to articulate some point about his career and the recent revival of both literary and motion picture interest in his life story, one can only wonder and speculate about most of the thoughts that are trapped in this still proud performer’s mind.

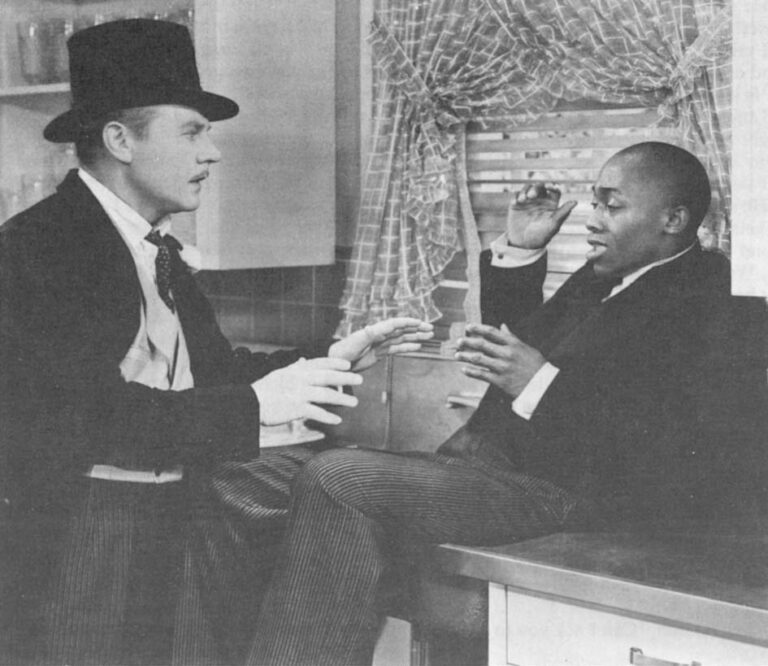

Miles south, in the fashionable Malibu area of the Pacific Coast Highway, a comedian of more recent vintage is also plotting his future – but the vistas are far wider and brighter. Still, there are some similarities and coincidental parallelisms between the lives and careers of these two comics. Like Lincoln Perry, Clerow Wilson spent much of his childhood in foster homes and boarding schools. Both are extremely religious: as Mr. Perry sits in his small hospital room methodically fingering his rosary beads, Mr. Wilson sits in his spacious study, a gold cross dangling from his neck and a large gold ring fashioned to spell the word GOD on his finger, and considers the merits of a script for a TV special on the trial of God. And like Mr. Perry, Mr. Wilson is one of the handful of contemporary comedians (Redd Foxx and Slappy White are among the others) who cut their comic teeth performing before primarily black audiences. For Mr. Perry it was on the vaudeville circuit as one of “The Two Dancin’ Fools from Dixie”; for Mr. Wilson it was the so-called “chitlin’ circuit,” small night clubs and honky tonks, and the Apollo Theatre. Then, too, Mr. Perry and Mr. Wilson worked together at one time. In the early 1970’s they made a pilot for a TV show in which Mr. Perry was to play Mr. Wilson’s father. It was never aired, however, because, as Mr. Perry says, “the producers decided I was ‘the epitome of the black man who sold out his people.”‘ The networks were wary of having Stepin Fetchit appear in a series with their bright new comic find – Flip Wilson.

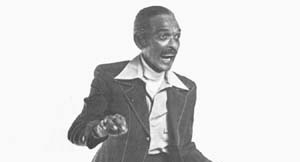

It has been five years since Flip Wilson appeared regularly on television and nearly 11 years since he worked the night club circuit. During that time he may have gained a little weight. There is a slight bulge at the midriff and perhaps a few more wrinkles accent his faintly cherubic face. But the diverting twinkle in his eyes and that beguiling combination of innocence and mischievousness still light his smile. He is ready, he says, to return to work. Future projects include a new TV show and a series of engagements in Las Vegas.

“Look,” he says, “I’m an eighth-grade dropout, and I haven’t worked for years. I made a plan when I started the show in 1969 about how long it would take me to get the security I needed for the rest of my life. When I got that I decided it was time for me to spend some time with my children. Some people said I was crazy, but I didn’t care. I knew what I went through as a child, so I spent five years with my kids. It didn’t take anything away from my popularity; I haven’t lost a thing. More important, I got to really know my kids – they’re my best friends. You know, if I hadn’t taken that time, people might have been saying, ‘Hey! He’s great.’ But they’d be saying, ‘He ain’t shit.’ Now, I got the whole cookie, and it’s time to get back to work. I’m ready.”

Flip Wilson’s stature as a comedian and entertainer are no longer in question. But being among the few entertainers who have successfully moved from the black theatrical circuit to stardom on a national level, I ask him about the change in the composition of his audience. Did it affect the style or content of his humor?

“I would say that I had to work at a higher energy level when I was doing that, working before all-black audiences. You had to, you know, because in a little club or a theater like the Apollo where people come in at the end of the week with about $20 left, they wantta have a good time. You got to work at a higher level to get their attention, and then hold it. You gotta keep the tempo up. It takes a certain talent, and you gotta work hard at it. Blacks want more effervescence – you gotta really be in it when you perform. It’s easier before white audiences because you can use more finesse and subtlety, you know. It’s not more fun, but it’s easier. I discovered that I didn’t have to drain myself as much. I could get the humor across with just inflection, the voice thing, not the entire body energy. I also knew many of the slang of hip expressions that I used in black clubs couldn’t be used because the audience wouldn’t know what I was doing. It didn’t have to be too different, because expressions get around; but you had to make sure the audience understood.

“Still, I’ve always said funny is not a color. Funny is, that’s all. Being black is only good from the time you get from the curtains to the microphone… I’m funny. I always wanted to be funny. But I’m not a black comedian. At the time, bcing black gave me a hook; it caught people’s attention because of the situation, you know, the civil-rights movement. And, because I’m black and culture is what I knew best. I expressed that.

“Wait! Let me tell you something. A friend once told me, a white guy, a businessman, and this is when I was struggling, you know – he said, ‘Look, I think you’ve got a lot to express. But you’re inhibiting yourself…. well, because you’re a “n…..”.’ He said, ‘Now that’s a word I don’t use, but I want you to understand. I think black people are too self-conscious about having been slaves. All nationalities have been slaves, and nobody has come back faster than you people… I’m amazed at black people, yet they spend all that time feeling sorry for themselves. The point is, it’s over. It’s over!’ He said, ‘Damn what anybody thinks of you. Say what you have to say and help open up somebody else’s eyes.’

“Right then, I realized something. So I said, ‘Yeah!’ That’s when I realized how interesting being black is. I said to myself, ‘Okay.’ They waitin’ to see a “n…..” who is ashamed or shy. No way! “N…..”s is fun. “N…..”s is good! We came back and said, ‘Hey, I ain’t mad. Screw it!’ I decided to enjoy myself – be myself. What I try to express is real. It’s what I know. I’m not tricking anybody. White people, people of many nationalities, have helped me all along. But from blacks, people I grew up with and people in the audience when I was starting out, I got that feeling. It’s like those little girls that sit right in front of the stage, and when they see something they really like – just for a minute – they let themselves go. They say, ‘Whooee!’ And for a second they’re free. I tried to get that in the character of Geraldine. They couldn’t give me nothing material, you know, but they gave me the inspiration. My humor reflects all of that. I could not be a part of, express anything that did not speak the truth of my own experience. I was telling an American story. It’s real and I think people understand that.

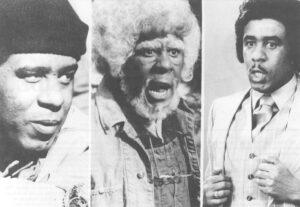

“And my show, with the characters I created, I was showing different faces of blacks. They expressed my values. I’ve never belonged to any group or organization, because I didn’t want anything watered down or taken away. I tried to bring out the real warmth of black people as I saw it… Reverend Leroy expressed my spiritual values. I had Geraldine to relate to the single girls. I had Freddie Johnson, the playboy, to relate to the single guys. And there were other characters. All of them came out of my own experiences.

“Geraldine, for instance, was created because many times when I was working the black clubs guys would come over and say, ‘Hey. Can you get me a girl?’ Guys were always hitting on the girls, and they didn’t even know who they were. I took offense, you know. I realized black guys wouldn’t just go into any club and hit on any chick, when he didn’t know who she was with. And they wouldn’t go into a white club and say to someone, ‘Can you get me a girl?’ I wanted Geraldine to show pride in herself, and dedication to her man. You know, she’d say, ‘Watch out! You can look if you want to, but don’t touch nothin’, sucker!’ I made her flashy, and she was not that refined. But she was strong, and her love for Killer was honest. Even with all the tension that existed at the time, I felt that, with people laughing at Geraldine and Reverend Leroy, the next day, when they went to work or to school they could open up a little – maybe understand black people more. That’s why I feel all the characters that I did were important. Whites didn’t know those types. For many of them it was the first time they had a black in their homes. They’d watch, and they’d laugh; maybe understand our humanity. I felt that the show helped.”

“What about the responsibility that goes with that kind of influence?” I ask.

“Okay, let me tell you a story,” he says. “Once, while the show was still on, I was sitting at the airport, waiting for a young lady to come in. I was sitting there in the Rolls, and I’m watching this young black guy standing there looking at the car. The glass was tinted, so he couldn’t see who I was. So he walks up to the car and taps on the window. I roll the window down, and he says, ‘Flip Wilson. You’re Flip Wilson!’

“I said, ‘Yeah! How you doing?’

“He says, ‘What’ya doin’ at the airport?’

“I said, ‘I’m just waiting on a lady friend of mine to come in.’

“’Is it a white girl?’ he asked.

“I said, ‘No.’

“He said, ‘Ahhh, come on. I bet you waitin’ on a white girl.’

“I said, ‘No, I’m not.’

“He said, ‘Yes you are. Any time a black star gets as big as you, they don’t mess around with our women any more.’ He said, ‘You know what, I’m goin’ stand right here and wait ’til she comes out. ‘Cause I know you waitin’ on a white girl.’

“So I said, ‘Okay.’

“He just stood there, beside the car; he didn’t say another word. I rolled the window up, and stayed there ’til the chick came out. She was a black woman. Then, when she got in the car, he tapped on the glass again. I rolled the window down, and he said, ‘You were tellin’ the truth weren’t you? You were tellin’ the truth.’ Then he said, ‘Can I meet your lady?’ So I introduced him, and he said, ‘How you doin’? Are you Geraldine?’

“She said, ‘No.’

“Then he said, ‘Can I ask you to do me a favor?’

“I said, ‘Yeah.’

“So he said, ‘You know, white people really love you. You know how much they love you?’

“I said, ‘I think I understand.’

“He said, ‘They believe you too. I think they’d listen to you if you told’um somethin’.’

“I said, ‘You really think so?’

“’Would you tell’um something for me?’ he asked.

“So I said, ‘What is it.'”

“He said, ‘Tell’um to do something. Anything. Just tell’um to do something about what’s happenin’ out here.’ Then, he walks away.

“I tried to do that.”

In the absence of established comedic stars like Flip Wilson and Redd Foxx, who brought their experiences from the black theatrical circuit to television, and others like Bill Cosby, who honed his talents primarily before integrated audiences, television has turned to a host of new black comedians. Among them, Robert Guillaume, formerly of “Soap” and now the star of “Benson,” is one of the most articulate and outspoken.

At his agent’s office on Sunset Boulevard, I ask him about the criticism of “Benson” as being a kind of extension of the negative, servile images of blacks established by shows such as “Beulah” or by characters such as Rochester of “The Jack Benny Show.”

“I don’t see Benson or his job as negative in any way,” he says. “It’s too easy to make that criticism. People are not known by the jobs they do, but by the way they conduct themselves. And what I’ve tried to insist upon in the Benson character is that he is in no sense chattel. He’s not tied in any way except employment to the people he works for. Even though we don’t see this other life on TV, I try to give the impression that he has a separate life. Also, the show is not straight comedy. I try to do a broad range of things with the character; in other words, I look at it as if I’m playing drama. One thing that separates Benson from Rochester or Beulah or most of the other black servant characters is that he’s capable of reacting in a serious manner. Now the others were capable of some serious emotions also. It’s just that the people who played those roles were hemmed in by the conventions of the times, by the attitudes of the people who asked them to play the roles. Apparently it was just not conceivable to them that the characters’ scope could be broadened. They were simply comic foils… What pleases me enormously about Benson is that he’s an ordinary person. He’s an ordinary black man, yet he is able to think. That’s important because the assumption of many people is that if you’re black and not some superhuman character, then, you’re dumb. And that’s not true, not of any group of people.”

As to authentic black humor on television, Mr. Guillaume says: “I don’t think there is a distinction between black and white humor in the sense of TV sitcoms. Most all of America’s humor, it seems to me is interrelated, intertwined. Especially since 25 years ago when Jewish jokes became generally public. The same thing has happened to most black humor… Now, I’d say that the thing that’s left, that may still be exclusive to black humor, is the compendium of looks, facial expressions, and silences that we developed at one time because we couldn’t say anything to anybody. If you did, you knew you might be lynched, because there was no way to fashion a statement that would conceal the anger, frustration and bitterness. We developed a whole style with the mouth and the eyebrows and even body language – that’s the source of much of our humor, I think.

“I guess that’s where much of my humor comes from. I mean, if Jessica Tate comes into the kitchen in the morning and sees me breaking eggs over a bowl, and asks me what I’m doing, I look at her with a certain expression, and I know it’ll get a laugh. See, there’s no other way to react. I can’t say, ‘Oh, well… I’m breaking eggs.’ But that particular look, that silent reaction is part of black culture. It’s so ridiculous that over the years they’ve asked so many simple – dumb questions! You get down to where all you can do is look at her and say, ‘Well, what’s it look like I’m doing?’ She says, ‘It’s eggs.’ And you say, ‘Good, then it’s eggs, sweetheart.’ But your expression, the raised eyebrows and lip sort of hanging, is saying, ‘Damn! How can you be so dumb?’

“I think that’s where much of today’s black humor comes from. It’s derived from the exasperation of having to deal with these people who don’t really realize what they’re saying. I think that’s why I initially got the role of Benson; it was the one thing I laid into the role that the others did not. I understood that we should show the cat’s disgust with people who are supposed to know so much but actually understand so little. If we saw that on his face we had to laugh. It was a reaction I had been afraid ofshowing for years. I was afraid someone would say, ‘Why you so angry and mean and nasty?” But when I did the test for ‘Soap,’ I was at a point in my life where I decided I would only do the things that were funny to me… I like to think that Benson reacts to the absurdity around him with what I call ‘mumbling on the face.’ It has a black source, I feel, but it’s become universal. Everybody understands it now…”

South of Sunset, on Melrose Avenue, is one of’ the centers for comedy in Los Angeles. It is Budd Friedman’s Improvisational Cafe. Inside, on any given evening, there are scores of comics who would give their best routines for a shot at a sitcom. Among them are several young black comedians, who, according to Improv regulars, are a cinch to make it. One of them is George Wallace.

“Hello there! Everybody okay? Yall having a good time so far. Yeah, well I’m goin’ stop that now… ha, ha. My name is George Wallace (pause). I know that’s a surprise to some of you, and perhaps a disappointment to others. Nevertheless, that is my name – l’m not responsible. A lot of people get stuck with names they don’t want… Take Mr. Greenjeans. Can You imagine going through your entire life with people referring to you as Mr. Greenjeans. Damn! And who in their right mind would name a kid Menachem Begin… Speaking of television, you know, TV has an effect on everything we do. Even driving here tonight – see, I stopped to get some gas, and they had a self-service island, a full-service island, and even had fantasy island. That’s where you think you get gas for 30Ë a gallon… I predict that in one minute we goin’ have a blackout – I’m leaving. Before I leave though, I want to answer one question. It’s mainly for caucasians, and you all have been asking this for years. The question is, do all black people know each other? Yes! Yes we do! When you see us shaking hands and carrying on, going through our little moves and whatnot – those are signals! We getting ready to go to a place far away, far, far away. It’s a place called Planet Avenue. As soon as we get that food supplement perfected, you know, the one that taste like chicken. Don’t worry you’ll know when we gone. When you wake up one morning and there ain’t no music on the radio – that’s it… You know, I came out here to have a good time tonight. I’d rather be here than in the best hospital in town. Wouldn’t you? (“I’m not sure.”) Who said that? You did. You know, you’re the very reason we have birth control pills… Say, have you seen that commercial on TV with the fat guy, Orson Welles; sitting with a glass of wine saying, ‘I know good wine.’ Let’s face it, the stuff he’s drinking is just one step above Thunderbird. ‘I know good wine!’ Who’s he kidding; he don’t know shit! He’s too fat to get up and find some good wine. Should be sayin’, ‘Will somebody call the tow truck, please?’…You know, I been up here for 15 minutes and some of you don’t know me yet. That’s why I carry this. (Shows an American Express card.) Now, it’s not mine, but I do carry it. What you better do is check your pockets and make sure it ain’t yours, cause this is what I use to open doors…”

Later, when another comedian takes the stage, I talk with George Wallace at the bar.

“Young black comedians are not following in the footsteps of their predecessors like Flip, Redd Foxx and the older comics,” he says. “America is not accepting that kind of humor now. Comedy is more serious. What we try to do is take some of the problems of the world and look at them from a fresh or different side. It’s more observation and opinion. Right now, for instance, there are a lot of jokes about the Iranians. You look at the bad things and turn them around to see the lighter side. Black comics are doing basically the same thing, but, because we’re black, there are some added things we can do. Still, we don’t tell jokes like Redd Foxx or Pigmeat Markham used to do… Of course, we all have characters that we do, and that sometimes touches on more black type humor. My favorite is my little old Southern lady. It’s based on an aunt of mine.

“See, she might say something like this;

“Junior said he wit Natalie Cole. Honey don’t believe that. Junior ain’t wit no Natalie Cole. Me and my sister drove a hundred miles, down there to San Diego to the jazz cool festival – we ain’t seen no parts of Junior. We seen everyone of them boys come out on that stage wit Natalie, but Junior ain’t no where ’round there. Then we seen boys come out after Natalie. What that boys name, you know, the singer – Teddy Tenderass. But we ain’t seen no Junior. The boy weren’t even hitchhiking on the road. That boy lying, honey. You take Junior’s brain and put it in a bird, and that bird goin’ fly backwards.”

He laughs, then pauses. “But, you know what,” he says, “I loved those old dudes. We’re going to miss them.”

©1980 Mel Watkins

Mel Watkins’ Fellowship study is Black Humor from Stepin Fetchit to Richard Pryor.