The Public Humor

Perhaps the most apt way to describe the public humor of black Americans prior to the mid-1930’s is to say that it was nearly always masked. Not only in the literal sense of grotesque, corked on blackface facades used in the minstrel shows that took the United States by storm in the early 1800’s, but also figuratively and psychologically. As an old blues tune put it:

Got one mind for white folks to see,

‘nother for what I know is me;

he don’t know, he don’t know my mind.

The humor displayed by blacks to those outside of their own ranks was of necessity oblique, sometimes double-edged, and usually at least superficially, self-deprecatory.

Slavery, of course, was the primary factor in molding these characteristics. Although bondage and oppression are hardly favorable circumstances for the development of a comic tradition, it was precisely from that situation that both the indigenous and public style of black humor arose. Its form, from the beginning, combined cultural elements common to the numerous traditional African societies from which the slaves had been taken and the new language, social institutions and behavioral patterns of ante-bellum America, to which blacks had to adjust.

Forbidden to speak in their native languages (and usually because of the diversity of their various tribal languages, unable to communicate verbally with fellow slaves anyway), slaves initially communicated with each other through physical gesture and the use of music and dance. Chanting, drumming, foot stomping, hand clapping and dancing has been an important part of the various rituals and religious ceremonies of most of the West African tribes from which the slaves had been abducted. Moreover, in those tribes, dance was a highly esteemed art, which was itself a means of communicating. (For instance, Robert Farris Thompson in “African Art in Motion” quotes an elderly member of a Cameroon Ngbe society observing a dancer as follows: “I like him because he uses the conversation with his body. Even an old man can dance conversation.”) Music and dance, then, were common points of reference, which permitted initial communication, among the disparate tribal groups enslaved in America. And soon those activities became the focus of recreation and merrymaking among the slaves.

“Childlike” Prancing

Eighteenth and nineteenth century writings from English and American sources attest to the vigor and enthusiasm of the slaves’ revelry as they danced, chanted and fiddled at various plantation gatherings. Almost immediately these functions caught the fancy of slave owners and the visitors who traveled through the South. The high-spirits, good humor and “childlike” prancing of the slaves were a source of great amusement to most whites and, as early as 1795, one traveler commented that the “blacks are the great humorists of the nation.”

The humor, of course, was not always as benevolent as it seemed. Already blacks had discovered that a happy, benign countenance was a great buffer against the brutality of slavery. The mask had appeared. Many of the strutting, prancing steps performed by slaves and greeted with such hearty laughter from whites were intended as satiric commentary on the highfalutin airs, pretensions and gullibility of their mastcr3. Dance and mu3ic for slaves were not only outlets for pent-up emotions and vehicles for communicating their feelings, hopes and frustrations, they were also a clandestine means of expressing rancor and dissatisfaction with their plight. Even so, these antics established a general pattern of acting out roles that accommodated the white view of blacks; and this pattern was to characterize much of black life and black humor for many generations.

Afro-American Patois

As blacks learned to communicate verbally in a type of Pidgin English the pattern was strengthened. Linguists have shown that many of the “aberrations” of black speech, or black English, resulted from the attempt, without tutoring, to conform African patterns of speech to American ones. Specific words such as “okay” or “dig” have African prototypes, which account for their initial use by blacks. (Okay is probably from the Wolof kay, meaning “of course,” or the Mandingo o-ke, meaning, “that being done.” Dig is also derived from the Wolof dega, meaning, “to understand.”) But, more significantly in terms of black humor, several modes of African speech were adapted and integrated into Afro-American patois. Whether accidentally or by design, a few of these African speech devices provided for the same type of furtive, masked expression of real feelings as did slave dancing. Comedian Redd Foxx expresses the fighter side of this phenomenon when he tells the story of an African learning to speak English from a white, Southern tutor: “‘Hey, boy. Bring dat dere yonder. Chunk it, “n…..”, chunk it.’ The African responds by saying: ‘Ooba gooba,’ which when translated, means: ‘Chunk that shit yo’self.'” 1

At the same time, because of their oddity and incomprehensibility for most whites, these rhetorical devices were considered amusing. They too became part of early black humor, even as they abetted the stereotype of the illiterate, fun-loving black in white America.

In “Talkin and Testifyin,” Geneva Smitherman enumerates some of the more prominent of these devices. Among them are “call and response…signification” (also called “ranking,” “sounding” or “the dozens”) and “tonal semantics.” Call and response is the most familiar of these, and is simply the extemporaneous interaction between speaker and listener or audience. For American blacks as for their African ancestors, the device allowed subtle communication between two parties in which listeners express approval or disapproval or, often, their awareness of the contradictory meaning of an assertion or statement.

Signifying

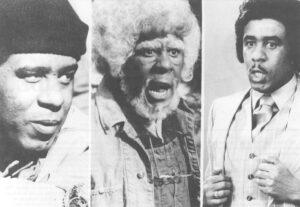

Signification or “signifying” refers to the art of verbally and humorously insulting a listener. Although it has antecedents in several cultures, it was promoted to the stature of ritual in many West African tribes, and is still a revered street game among Afro-Americans. (Its impact on comedy can be seen from minstrelsy to contemporary comedians such as Don Rickles and Richard Pryor and in such show business ceremonies as celebrity roasts.) Tonal semantics is the practice of using voice inflection and altered rhythm of speech to convey meaning in discourse. With its use practically any word can assume totally contradictory meanings (For instance, the adverb “yeah” can express anything from enthusiastic approval to sardonic incredulity.)

These linguistic devices, like much slave music and dancing, served two purposes. In the presence of their masters they could present the docile, grinning and submissive image required, and, at the same time ‘ convey to their fellows some of the unacceptable feelings of disrespect and hostility that they felt.

In the privacy of the slave quarters much of the pretense was dropped. Slave narratives and black folklore collections relate numerous instances of blacks shedding the “dumb coon” posture, which amused whites had come to accept and expect, and adopting a sharper edged humor. The following version of the story of Pompey and his master is a fine example:

“Pompey, how do I look?”

“O, massa, mighty. You looks mighty.”

“What do you mean ‘mighty,'” Pompey?”

“Why, massa, you looks noble.”

“What do you mean by ‘noble’?”

“Why, suh, you looks just like a lion.”

“Why, Pompey, where have you ever seen a lion?”

“I saw one down in yonder field the other day, massa.”

“Pompey, you foolish fellow, that was a jackass.”

“Was it, massa? Well, suh, you looks just like him.”

Uncle Remus

Other notable examples are the stories collected from blacks by Joel Chandler Harris (1848-1908) and told through the fictional character, Uncle Remus. Although not published until 1880, these folk fables were typical of the tales blacks related among themselves during slavery. In them, Brer Rabbit (“the weakest and most harmless of all animals”) consistently outwits the fox, bear and wolf. Like the Aesop fables, which were brought to Greece by black slaves, these tales had their origin in Africa’s complex pantheon of animal deities. The tales collected by Harris had been altered to fit the circumstances and environment of Southern America, but they maintained the theme of the underdog outsmarting his more powerful foes. Even though the Remus stories were extremely popular at the turn of the century, initially few whites recognized the significance of their satire. Even Harris seemed to be unaware that they were veiled protests against slavery.

What white America had become aware of during slavery was the comforting and amusing presence of the obedient, happy-go-lucky black to which they were most often exposed. They saw only the quaint mask that blacks had adopted in order to survive their bondage. And it was this image of blacks that white America chose to imitate on the stage.

Burnt Cork

Using burnt cork to blacken their faces, white performers began touring the country in the early 1800’s billing themselves as “Ethiopian Delineators. ” From the offset, they claimed that their portrayal of blacks were authentic representations, just as traveling showmen had insisted that early portrayals of the New England Yankee type and the backwoods or frontier Davy Crockett type were realistic representations. As a young nation, still embarrassed by its lack of cultural tradition and sophistication when compared to the longstanding cultural heritage of its English parent nation, in its comedy America had elevated the qualities of rural wit and pioneer inventiveness as a foil against snide British critics. (America’s greatest 19th century wit, Mark Twain, would emerge from this comic tradition later in the century.) The broad farcical humor that white observers saw in blacks fit perfectly into this tradition. And there was an added advantage: with blacks as the butt of the jokes, the humor allowed whites to laugh at a type to whom they themselves felt superior. Blackface humor needed only the proper catalyst to become America’s primary entertainment attraction.

In about 1828 Thomas “Daddy” Rice, a traveling entertainer provided the needed stimulant. After observing a crippled black stable hand dancing and singing a jingle (“And every time I turn about, I jump Jim Crow”), Rice began imitating the dance and song. It is said that he even bought the youth’s ragged clothes to add authenticity to his imitation. When he added the dance to his stage act, he became an instant hit. “Jim Crow” shows began to spread across the country as numerous imitators copied Rice’s act. In the 1840’s, after Daniel Emmett embellished the “Jim Crow” theme and billed his act as the Virginia Minstrels, blackface shows became America’s most popular entertainment. Minstrelsy was born, and the public image of black humor established. That image would persist with only slight alteration for nearly a century.

Mr. Bones

Minstrel shows quickly evolved into a stylized, three-act format. Comedy was the essential ingredient, although song and dance were included. Performers appeared on stage in a semi-circle facing the audience with a combination M.C./straight man, called the interlocutor, seated in the center. Characters called Mr. Bones and Mr. Tambo were seated at each end. The repartee, among these three characters provided most of the humor, although the end men were the most important performers. Their antics, dances and sharp wit established basic prototypes that became standards for American humor.

Much of the material for these shows, particularly the dances, was taken directly from Southern plantations. The juba (a rhythmical hand-slapping routine now often called the hambone) and stick dance were of African ancestry. The jig was an African variation of European folk dance, and the cakewalk was a dance used by slaves in satirical imitation of their masters.

The jokes themselves were a curious mixture of black dialect and some word games borrowed from slaves combined with the humor already established in the Yankee Doodle and backwoods comic tradition. The songs were imitation (or often direct borrowings) of black field songs and spirituals; well-known composers such as Stephen Foster contributed much of the music.

The success of these shows notwithstanding, they were anything but the “authentic” representations of blacks that they were advertised to be. The blackface performers grossly exaggerated every action that transpired on stage. Minstrel arts, then, were initially performances featuring whites parodying the amusing antics of black slaves. It was a curious phenomenon, since the behavior being satirized was itself a parody of white behavior. It became even more convoluted when black performers, wearing blackface, formed their own minstrel shows.

Although black performers did add some authenticity to minstrel acts, generally they were forced to adhere to the same wildly exaggerated representations of blacks that had been previously established. The public and the producers of the shows demanded it. There were exceptions such as William Henry Lane, who was one of the few blacks in minstrelsy prior to the Civil War. Lane added a new dimension to his act by combining elements of the Juba dance with the Irish jig; he is considered the creator of tap dancing by most historians. Generally, however, after the first all-black minstrel show was formed, public humor was firmly locked into the derogatory stereotypes established by Thomas Rice and Daniel Emmett in the early 19th century. The vision of blacks projected by minstrelsy-a travesty in which whites parodied blacks satirizing whites-became the nation’s “real” image of blacks. It remained so for some time.

Interest in minstrel shows began to fade near the turn of the century, as vaudeville shows became more popular. But, despite the gradual decline of the minstrel format, the black comedic image was not altered. Blackface and the familiar “shuffling coon” continued as the core of black stage presence. This new era, however, produced the first black comic genius.

Bandana Land

Bert Williams and George Walker began performing in variety shows on the West Coast and Midwest in the late 1890’s. They billed themselves as “The Two Real Coons” to distinguish themselves from the still numerous white acts working in blackface throughout the country. Success did not come immediately to the team. But, in 1899, after several years on the vaudeville circuit they created their own show (called “A Lucky Coon”) and began a tour of the country. Their popularity increased rapidly. By 1902, their fourth show (“In Dahomey”) had reached Broadway, and the critics gave it a rave reception. After a long run in New York, the show moved to London where it received similar acclaim. Their biggest hit, “Bandana Land,” opened in New York in 1907, and confirmed the team’s reputation as legitimate stars of the stage. But tragedy struck shortly afterwards when George Walker suffered a stroke in 1909. After his death, two years later, Bert Williams became a single act.

Williams continued to work until his death in 1922 and, during that time, established himself as a comic talent without peer. A Theatre Magazine critic called him “a vastly funnier man than any white comedian now on the stage,” and Eddie Cantor, who worked in an act with him occasionally, remarked that “whatever sense of timing I have, I learned from him.” The comments are extraordinary considering that black performers were generally ignored by trade papers and established white actors. In 1910 Williams signed to star in the “Ziegfield Follies,” and much of his later career was spent in those annual spectaculars. He died a heavy drinker who could never reconcile his stage acclaim and plaudits with the contemptuous treatment he received off the stage as a black man.

A Black Chaplin

For all his success, Williams never significantly altered the “coon” image that continued to stultify public black humor. He still worked in the minstrel mold: blackface, funny dances such as the cakewalk, and a sad Tom-like posture. But he did add an element of sensitivity, even dignity, to that portrayal; his depictions of downtrodden, pathetic characters were comic classics. The possibilities for this type of bumbling, sad-sack comedic character, without the restrictions of race, were realized in Hollywood in the person of Charlie Chaplin.

The careers of Williams and Walker reflect the general atmosphere in which black stage performers worked during the early 20th century. It was a time of subtle alteration of the minstrel image; although the “coon” caricature remained, it was being expanded enough so that some trace of humanity was included. Other teams such as Flourney Miller and Aubrey Lyles attained stardom and, eventually, worked with Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle in “Shuffle Along” (1921)-a groundbreaking musical that moved black humor from the rural setting established in minstrelsy to the urban background of the city and the glossy style of the Jazz Age. And writers Bob Cole and Will Cook created several musical shows in which the rhythm of ragtime replaced the hoedowns, fiddles and banjos of minstrelsy.

The TOBA Circuit

Also, in the early 1920’s, a new circuit opened for black performers. Called TOBA, it was put together by the Theatre Owners’ Booking Association, and gave comedians the opportunity to play black theatres in major cities throughout the South and Midwest. Performers such as Pigmeat Markham, Spo-De-O-Dee, Moms Mabley, Ethel Waters, Buck and Bubbles, Mantan Moreland, Tim Moore (later Kingfish on the “Amos and Andy Show”) and Sammy Davis, Jr. (who at age four, in blackface, played a 40-year-old midget in his uncle’s act) emerged from the TOBA circuit.

It appeared that a substantial change in black humor was imminent. On Broadway, while the blackface caricature remained, the switch from rural to urban settings allowed blacks a flexibility of subtle interpretation, nuance, that had never existed in minstrelsy with its plantation backdrop. And on the TOBA circuit and in small clubs and honky tonks, performing before black audiences, comedians were developing a freer style of comedy in which segregation jokes and a more assertive, dignified approach to humor was apparent.

Hollywood

In Hollywood, however, a far more influential medium than the stage had developed.

Motion pictures were maturing as an art form, moving out of the nickelodeons and into large, plush theatres whose audiences were all white. From their inception, films had mirrored the derogatory caricatures of minstrelsy. The Southern literary tradition with its notion of “Southern virtue and black fealty to it” had also been accepted wholeheartedly by the coterie of moguls who controlled the industry; thus the screen had added its own stereotype-the loyal servant. D.W. Griffith’s “Birth of a Nation” (1913), even as it advanced the technological and aesthetic growth of motion pictures, had severely damaged the already hobbled black image.

The Hollywood image of blacks was confirmed by the mid-1920’s. So, even while events in the urban areas of the country, which the TOBA circuit reached, and on Broadway began to reshape the deprecatory image that had molded public black humor, Hollywood remained disinterested. The vigorous upheaval of style (both on and off stage) in the cities of the Northeast had barely touched the lives of filmmakers living in the expansive, rolling hills of southern California. They sought an image compatible with their own perception of black life, one which would be readily acceptable to the middleclass white audience they hoped to attract. And even as the first “talkies” were being filmed, black roles were restricted to the standard servants and shuffling darky types.

Consequently, the first black star to emerge from motion pictures was Lincoln Perry, who became an instant success with his role in “Hearts of Dixie” (1929). Prior to this role Perry had worked the TOBA circuit with another black comedian, Ed Lee. They had called their act “Step and Fetch It.” Perry adopted the name, and between 1929 and 1935 made 26 films. Despite the ferment and expansion of black comedic roles on the stage, the “coon” character portrayed by Stepin Fetchit and less luminous performers in films would dominate public black humor and the American view of blacks for years.

Endnotes

1) From “The Redd Foxx Encyclopedia of Black Humor,” by Redd Foxx and Norma Miller, Ward Titchie Press, 1977.

©1979 Mel Watkins

MEL WATKINS’ Fellowship study is Black Humor from Stepin Fetchit to Richard Pryor.