Seven thirty a.m. the sale barn. New Liberty, Iowa. A cold, rainy spring morning. The farmers in their blue and gray and white striped denim pants and jackets, their red, green and yellow billed caps, men of all sizes and appearances stand talking of how late plowing is this spring and of late spring plowing in seasons past. George, the spring of sixty-four was cold, too, darn it, the fellow says. We had to light hay fires, four nights in a row, May 20 to May 23, and you’d have to go some to find colder, wetter spring than that.

The bidding begins at 9:30 a.m. Today, Tuesday, is the day the sale barn sells cattle ready for slaughter, fat cattle, as they are known, and group by group the huge, snorting cattle, manure stuck to their legs, are driven into the sale pen. George Bruhn, a farmer from Durant, ten miles to the southwest, buys nothing this day. He might have bid, taken some cattle and fed them some more, even though they are marketable now. Once, some time before, he had bought steers for feed, spending two or three thousand dollars, raising a finger, a hand, in a gesture that was so quick it could not be discerned except by someone with knowledge of the arcane folkways of cattle buying. But today prices are too high, more than 60 cents a hundred weight for the 1000-pound animals.

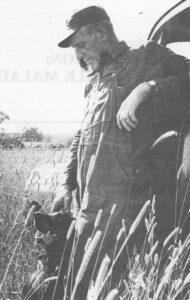

Mr. Bruhn, 62, is what may be a rarity in America, a good, happy man. He and his wife, Alice 63, have worked hard all their lives. They own 160 acres of eastern Iowa farmland, so rich that, although it has been farmed more than a hundred years, the black topsoil is still more than a foot thick. The farm is what would be regarded by many as the typical American farm. This spring Mr. Bruhn planted 80 acres of corn, 35 acres of oats and 35 of hayland. There are two fine, old barns, one with a splendid pulley system, an intricate contrivance of blocks and tackles and thick brown rope for hauling up bales of hay and straw. The farm has some 300 Lacombe hogs and 150 Angus steers. Mr. Bruhn raises the hogs himself and purchases the steers, most of them having been born in Western states like Kansas, Wyoming or Nebraska, and fattens them for market at the Joliet, Illinois, stockyard, one hundred-fifty miles to the east. There is a black and white dog, Duke, of no pedigree, the devil to rabbits and skunks, and a half dozen cats, including one, a large, black fellow, that spends his days in the hay barn and, it is suspected, his nights roaming where his fancy takes him. Although it is a cat that wandered in, no formal member of the Bruhn family, Mr. Bruhn puts cat food out for him in an old can under the cattle feeder.

Mr. Bruhn, 62, is what may be a rarity in America, a good, happy man. He and his wife, Alice 63, have worked hard all their lives. They own 160 acres of eastern Iowa farmland, so rich that, although it has been farmed more than a hundred years, the black topsoil is still more than a foot thick. The farm is what would be regarded by many as the typical American farm. This spring Mr. Bruhn planted 80 acres of corn, 35 acres of oats and 35 of hayland. There are two fine, old barns, one with a splendid pulley system, an intricate contrivance of blocks and tackles and thick brown rope for hauling up bales of hay and straw. The farm has some 300 Lacombe hogs and 150 Angus steers. Mr. Bruhn raises the hogs himself and purchases the steers, most of them having been born in Western states like Kansas, Wyoming or Nebraska, and fattens them for market at the Joliet, Illinois, stockyard, one hundred-fifty miles to the east. There is a black and white dog, Duke, of no pedigree, the devil to rabbits and skunks, and a half dozen cats, including one, a large, black fellow, that spends his days in the hay barn and, it is suspected, his nights roaming where his fancy takes him. Although it is a cat that wandered in, no formal member of the Bruhn family, Mr. Bruhn puts cat food out for him in an old can under the cattle feeder.

The Bruhns make a nice living, although there were times, not that long ago, when life was difficult, when they were getting started and building the farm. His wife was once a hired girl and, she, like her husband, recalls the awful times of the Depression, when there was almost no money; she talks of hard work she has done, not with braggadocio, but in a matter-of-fact manner saying that was how it was.

The children, a boy and a girl, are grown and gone, off to the city, and what will happen to the house, the buildings, the land, is not clear. What is now the kitchen of the farmhouse was, in the 1800s, when the farm was established, essentially the entire house. The house has been expanded over the years, and the Bruhns have made many improvements, a summer porch, a bathroom, cupboards, a washer and dryer. Once, when the kitchen was remodeled, the workmen tore out a wall and found it was filled with corncobs; the pioneers had used them as insulation. And among the corn cobs the workmen found a hand-carved last for a child’s shoe.

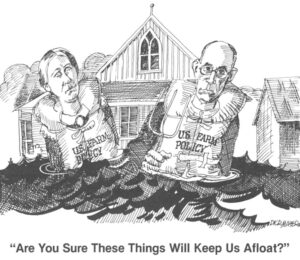

Today American agriculture is beset by two forces. First, the city is dominating the country. Cities are consuming vast amounts of prime farmlands, the flurry of excitement over land use controls of the 1970s to the contrary. Corporations seek out rural areas for new offices and plants, and build, not in the old downtowns of small cities, but on farmlands on the outskirts. Sub-dividers choose the best farmlands, flat and rich, for their houses, for this is easier to build on than hills or woodlots.

Along with this, a city style is altering life in rural areas. A national culture has emerged, and rural culture cannot resist it. Many farmers no longer have vegetable gardens. The high school in Durant, Iowa, two miles from Mr. Bruhn’s farm, no longer teaches agriculture. Wooden barns are a thing of the past, to be preserved in coffee table books; today’s barns have pole frames and metal sides and roofs — they are metal sheds. Regional cooking is practically nonexistent. Oshkosh B’gosh blue shirts now come in 50 per cent polyester. The expressway system, truck transportation, television, package foods, chain stores — all undermine rural culture, and rural culture collapses, as assuredly as if it were some strong redoubt, and sappers had tunneled under it, set charges and blown it up.

Second, American agriculture is being industrialized. Only 4 per cent of American farms are described as corporate farms, leaving 96 per cent as family farms. Yet this 4 per cent accounts for a substantially greater share of American farmland. And the corporate farms bring an industrial style-bigness, constant expansion, big, new equipment — that is transforming agriculture as it has transformed many areas of American life. It is a style not merely being forced upon farmers. Many farmers and farm area people, the real estate men, the bankers, the men, who sell seed, the farm implement salesmen, the fertilizer men, are eagerly seeking it out and embracing it.

Today 7.8 million Americans are classified as members of farm families, 3.6 per cent of the nation’s population. In 1977 alone, 450,000 Americans left farming, continuing a trend that has existed for years. At the same time, the size of American farms is increasing, in large part to take advantage of new, big machinery. For 1978, the average sized farm in the United States, reports Wallace’s Farmer, the famed Iowa farm magazine, stands at about 400 acres, an increase of about 50 acres from the mid 1960’s, almost twice the size of farms in 1950.

Most of these large farmers would say that they need to expand to keep up with today’s farm economy. But many studies, including a number done over the years by the Department of Agriculture show that a family-sized farm — that is, a rather modest farm of, say, 160 to 240 acres, operated by a family — is the most efficient farm, producing the lowest-priced food for consumers.

In 1947, a researcher, Walter Goldschmidt, studied two farm communities in the Central Valley of California. One, Dinuba, was largely a community of small farmers; the other, Arvin, was an area of large farms. He found that the community of family farms possessed more retail stores, more parks, more community organizations and was, in short, a better place to live. In 1967, a U.S.D.A. economist, J. Patrick Madden, reviewing nearly 140 studies of farm efficiency, found one-and two-person mechanized farms to be the most efficient. This was true for dairy farms, fruit farms, crop-livestock farms in Iowa, vegetable farms in California’s Imperial Valley. Mr. Madden concluded, “All the economies of size could be achieved by modern and fully mechanized one-man or two-man farms.”

Farm income, says Secretary of Agriculture Robert Bergland, will hit $25 billion during the current fiscal year, a 22.5 per cent increase from $20.4 billion of the previous fiscal year, and the third highest farm income year in history. In recent months, Bergland says, prices received by farmers have increased dramatically — 30 per cent for wheat, 40 per cent for corn, 30 per cent for soybeans, 40 per cent for cattle.

How is the American farmer doing? Is he getting a fair share of the price that the American consumer pays for food? Is the American consumer paying a reasonable price for food? How good is the food that the American farmer produces and the shopper purchases and consumes?

The American farm and food industries are intensely complex. And, despite the importance that food plays in the American life and the American economy, a surprising lack of information is available.

However: many American farmers are making surprisingly good profits. Many are in trouble, but, in a number of cases, they brought on trouble — and thus helped increase the cost of food — by their own actions in purchasing more land and machinery. And the American consumer, while they grouse about rising food costs, still somehow have enough money, and are careless enough, that they are not only poor consumers, buying more costly foods, but spend an amazing one third of their food money on meals away from home.

Farmers face constantly rising costs, so much that, according to Carol Tucker Foreman, assistant agriculture secretary, it takes an estimated $500,000 to purchase a farm and begin food production. Each year, farmers must make major outlays for seed, fertilizer, pesticides, machinery, livestock. The profit margins on these capital costs can be surprisingly low.

Yet, many of the problems of farmers — in the last year it is the wheat growers of the Great Plains who have suffered the major financial problems — are of the farmers’ making.

The Richard Nixon administration was extremely good for many American farmers. The years of 1973 and 1974 saw the extensive sales of grain to Russia as well as high prices for wheat, soybeans and corn. It may be that farmers take good times badly. Many, apparently believing the good times would not end, spent record amounts on land and machinery. The sales of International Harvester and John Deere jumped by billions of dollars between 1972 and 1974.

The bidding for land drove up its price. In some cases, fine Midwest farmlands, like those in Iowa, rose several hundred of dollars an acre. Prices of more than $3,000 an acre have been reported, although land advertisements in recent Des Moines Register editions do not reflect prices that high.

Credit was no problem, for land or machinery. Years ago, the agricultural historian, Paul Wallace Gates of Cornell University, wrote in his history of early American farming, The Farmer’s Age: 1815 to 1865, that problems for farmers arose not always because of a lack of credit, but “sometimes (because) credit came too easily.” He added, “It was when farmers borrowed for speculation that they took serious risks.” The same held true in the early 1970s. The primary rural credit institutions, local banks, the Production Credit Associations, the Federal Land Bank, happily advanced funds, assuming, probably correctly, they would have no trouble collecting on their loans.

Finally, tax laws encouraged land and machinery purchases, for interest and business expenses are deductible. “A lot of them invested in land as an alternative to paying taxes,” says Ken Robinson, a Cornell agricultural economist. “They made big money and brought tractors and equipment…Farmers would rather put their money in land than in the bank — or pay it to Uncle Sam.”

Then farm prices dropped. And many farmers, with extensive debts, faced financial troubles.

At the beginning of 1978, farm debt stood at about $120 million, up 100 per cent since the early part of the decade. The interest on this debt, Forbes magazine reports, consumes perhaps 50 per cent of farm income.

It was the financial difficulties that some farmers, particularly wheat farmers, faced, that led to the formation of the American Agriculture Movement — supported only faintly by established organizations, like the National Grange, the American Farm Bureau, the National Farmers Union, the National Farmers Organization — that demonstrated in many places across the United States, including the steps of the Capitol, in support of their demands for 100 per cent of parity, a demand that few economists take seriously.

Mr. Robinson calls the recent farm legislation, which raised the target price for wheat to $3.40 from $3.00, a “wheat grower’s relief act.” He says, “They went out and bought expensive tractors and equipment, and now they want the government to publicly ratify those decisions by maintaining the incomes that were necessary to pay for the high-priced land and equipment.” He declares, “In the past, we thought of price supports as setting a floor under variable costs, preventing a disaster. We never thought about price supports as guaranteeing a profit.” He says, “A lot of farmers are just not that bad off.”

An especially knowledgeable rural banker, Oliver A. Hansen, president of the Durant, Iowa, Liberty Trust and Savings Bank agrees. “These fellows who have got their farms paid for, or a fellow who’s got his farm practically paid for, is going to be all right,” he said. “The guy who went out and bought some high-priced land and made some heavy capital investments, like harvesters, and silos, and feeding setups, and confinement units, and so on . . . those are the ones who are going to have problems.” He adds, “There is a vast amount of wealth out there, so that even if things got a little tough, there would be problems, yes, but they wouldn’t be general problems. They would be individualized, isolated problems. And some of the rest would have to change their standard of living.”

The Bruhn family has farmed in Iowa for more than half a century. It is, in its way, a part of Middle West — of American — history. Mr. Bruhn’s father, Adolph, came to this country from Germany in 1900. He was 14, and he traveled alone, except for two young friends, whom he never saw again after his boat landed in New York. He was sent on a train across the country to Iowa, where a sizeable German population had settled, and Adolph Bruhn made a life on the farmlands of the Middle West. Just a few years ago, when he was in his eighties, he and his son, on Sunday afternoons, would sit in the living room of the Bruhn’s place and, while the women did the dishes in the kitchen, talk in German. Adolph Bruhn is dead, and there is no one for George Bruhn to talk to in German now.

When George Bruhn was a young man, starting in farming, he plowed one day the last stretch of Iowa prairie that people knew of in that part of the state. Once the Iowa prairie, like that throughout the Middle West, stretched to the horizon. In 1835, a government explorer, Stephen Kearney, led a troop of soldiers through this part of the state; the grasses were so high that the horsemen could braid them across the horses’ backs. The track was red with wild strawberries, and the soldiers, who drove cows with them, had fresh strawberries and cream to the headwaters of the Des Moines River. When Mr. Bruhn plowed that prairie, the sod, thick with grasses, laid over like a long, black ribbon. He plowed with horses then, and when he planted corn, he planted the corn as deep as the holes made by the horses’ hooves.

Now, there are tractors and combines and corn pickers, but he and his wife still work hard, planting oats and corn and feeding his hogs and cattle. He is, in many ways, typical of hundreds of thousands of other American farmers. Yet, too, he is untypical, for he does not seek, nor is he impressed by, the new ways, the massive machines, the continued expansion of farms, the city ways. This is not to say he is a man who lives in the past, that he is opposed to better ways. Yet, his life is marked by proportion, balance. He is a man without greed.

When he and his wife leave farming, what will happen to this farm? And what will happen to the farms of thousands of other farmers like him, farmers in every part of the country? And of the hundreds of thousands of farmers who do not farm like him, the men who seek the new machinery, the new chemicals, who engross other lands to expand their own; and of so many of the rest of the people in this country, people who believe in, people who prosper by, the way we live; who of them will care? That is it: who will care?

©1978 William Serrin

William Serrin is spending his fellowship year writing about ” Farmers, Food and Farming.”