(a) Helps (b) Hurts The American Farm

In the autumn of 1921, George N. Peek and Hugh S. Johnson, executives with the Moline Plow Company, Moline, Ill., proposed a plan to aid the American farmer. The early 1920s were hard times for farmers. Many had prospered in the first two decades of the century, particularly the years before and during the war. But the end of the war had brought a reduction in markets, and farm prices dropped dramatically. Farmers who had gone into dept to purchase more land when prices were high were unable, with falling prices, to make their mortgage payments. Many farmers lost their farms.

Peek-a farm machinery executive for many years, a go-getter, and, particularly in his later years, a strong isolationist-and Johnson-a classmate of Douglas MacArthur at West Point, a brigadier by the end of the war, and, later in the 1930s, administrator of the National Recovery Administration-said that the farmer had one major enemy: surplus.

Despite tariffs, Peek and Johnson said, surpluses forced American farm prices down. Yet, manufactured goods that farmers had to purchase sold at higher protected prices. Peek and Johnson proposed that surpluses be purchased by the government and eliminated from the domestic market. Enough farm products would be sold domestically to supply consumer demands at a “fair exchange value,” the level of prices that had existed in the ten years before the war, 1906 to 1915, a period known fondly, even then, as a golden age of agriculture. The fair exchange value would be established by law and protected by a fluctuating tariff. The government purchased surpluses, meantime, would be sold by the government on the world market; any losses would be paid by an equalization tax on all farmers, spreading the losses to everyone.

To popularize the plan-this was a time, remember, of the growth of advertising, of sloganeering- Peek and Johnson coined the slogan, “Equality for Agriculture”, a phrase that soon became known around the country. In the coming years, this concept was shortened to a single term, one still a measure of the prices farmers receive, and one still fiercely contested: parity.

The Peek-Johnson plan, which the two pushed with their own time and money, became one of the most bitterly argued legislative proposals of this century. Adopted in what became known as the McNary-Haugen bills, named after two Western legislators, the measure was passed by Congress in 1927 and 1928 and twice vetoed by President Coolidge. Then in 1929, the Depression that had struck agriculture in 1920 struck the nation. Early in 1933, the new President, Franklin D. Roosevelt, gathered a number of farm leaders in Washington and asked them to agree on a farm plan. In May, the new farm law, the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933 was signed by the President. Its goal was parity.

Under the act, the secretary of agriculture was instructed to maintain the “purchasing power” of farmers at the level that had existed between August 1910, and July 1914, that era of good times. The act provided for market regulation through voluntary agreements between the government producers and processors, and for processor taxes to subsidize exports. The act also established acreage controls, under which, in an effort to reduce farm output and thus raise farm prices, the government would pay farmers to cut back the land they cultivated.

In January 1936, the U.S. Supreme Court declared the acreage controls and processing taxes unconstitutional. In February, Congress retaliated by passing the Soil Conservation and Domestic Allotment Act of 1936, which maintained the concept of government payments to farmers who reduced acreage. Then, Congress passed the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938, authorizing funds for a price support program and for storage of farm crops acquired by the government. This act-the first to specifically use the term parity-also contained programs for loans, marketing quotas for basic crops, and continued acreage restrictions.

This act, embodying the principles of Peek and Johnson, became the cornerstone of agricultural programs that have lasted for forty years.

United States history is, in many ways, a history of farms, farm protest, and legislation enacted in the name of the farmer. We must understand this history if we are to know how the American farm and the American farmer stand today, if we are to question farm policies and determine what the future may hold.

It is generally held in the United States that, from the founding of the nation to the closing of the frontier, the nation, in a zealous fashion, provided cheap or free farmland to its citizens. This is far from the truth. During the first decades of western settlement, from the Northeast Ordinance of 1787 to the Civil War, land laws favored profiteers and speculators and were constantly fought by reformers and agrarian leaders who struggled to reduce the size of plots made available, so speculators could not lock up large sections, and to reduce the price, so settlers could afford land.

In 1862, the years of agrarian demands led to passage of the Homestead Act, which promised 160 acres of free land to a farmer who worked a claim for five years. But that act, although it is still regarded by many as the embodiment of democratic legislation made comparatively little land available to settlers. Preemption laws still in force and future acts, like the Desert Land Act and the Timber and Stone Act were used by speculators and timber and mining interests to thwart the goals of the Homestead Act. Many areas of the West, past the 100th meridian, could not without irrigation support 160-acre farms. The railroads were given gigantic areas of lands, perhaps 180 million acres in all, which were thus withheld from free settlement. In his valuable work, Virgin Land: The American West as Symbol and Myth, Henry Nash Smith says that between 1862 and 1890, only 372,659 entries were perfected under the Homestead Act, and that, at most, two million settlers could have benefited from the law, during a time that the population of the Western states increased by ten million in the first two decades of the 20th Century, a slackening in the growth of cultivated lands and continued population growth raised the fortunes of many farms, although not, by any means, all of them, despite the description of the time as a golden age. Even during this time, mortgage indebtedness rose among farmers and farm tenancy was high, this in the nation that according to myth gave millions of acres of land to its citizens.

Then came the agricultural depression of the 1920s, and the Great Depression of the 1930s, and the farmer assistance programs pioneered by Peek and Johnson. As early as 1935, President Franklin Roosevelt remarked in Nebraska that “cooperative efforts in which the farmers themselves, the Congress, and my administration have engaged have borne good fruit.” That year, farmers received $573 million in federal farm payments; gross farm income rose to $9.6 billion, up from $6.4 billion in 1932; net farm income increased to $4.5 billion, up from $1.9 billion in 1932. The parity index advanced from 58 to 88 percent of parity.

But it was World War Il and what the war brought for farmers- increased markets, higher prices, expanded mechanization, increased use of fertilizers, insecticides, fungicides-that changed American agriculture. “Food will win the war and write the peace,” a slogan went. The amount of food produced was enormous, and prices were good. Between 1941 and 1952, farm prices were between 100 and 115 percent of parity every year except 1949 when they stood at 99 percent of parity.

During the Eisenhower administration, Secretary of Agriculture Ezra Taft Benson, an ardent opponent of high price supports and direct government payments to farmers, won Congressional approval for lower price supports and reduced acreage controls. Poor Benson. Government farm costs and surpluses rose sharply, and farm income fell, Benson was stridently attacked by many farmers and farm groups.

During the President Kennedy-Johnson years, domestic and foreign food distribution programs were increased, not, essentially, to help the world’s poor, but to reduce American surpluses. American exports increased markedly, and farm income showed some improvement. Government storage during the 1950s and 1960s cost the government-the taxpayer-billions of dollars.

Major changes for farmers came during the Nixon administration. Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz was determined to raise farm income. As part of that strategy, perhaps $300 million worth of American wheat, 400 million bushels, a third of the crop, was sold to Russia in 1972. In 1973, a new farm law, the Agricultural and Consumer Protection Act, introduced the concept of target price subsidies. Deficiency payments were established for farmers when crop prices fell below the target price. Farmers also could receive crop loans at levels below market prices. To receive the aid, farmers had to agree to acreage allotments. Prices fell in 1976 and 1977, however, and many farmers, particularly those who had purchased lands at high prices, faced dramatic problems. A number, banded together under the American Agricultural Movement, demonstrated around the country in 1977 and 1978, and are expected back this year as soon as their crops are in. One of their demands is that old goal, equality for agriculture- parity.

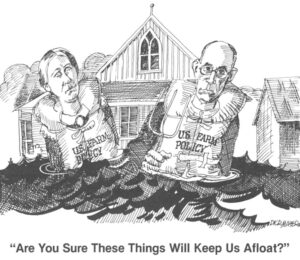

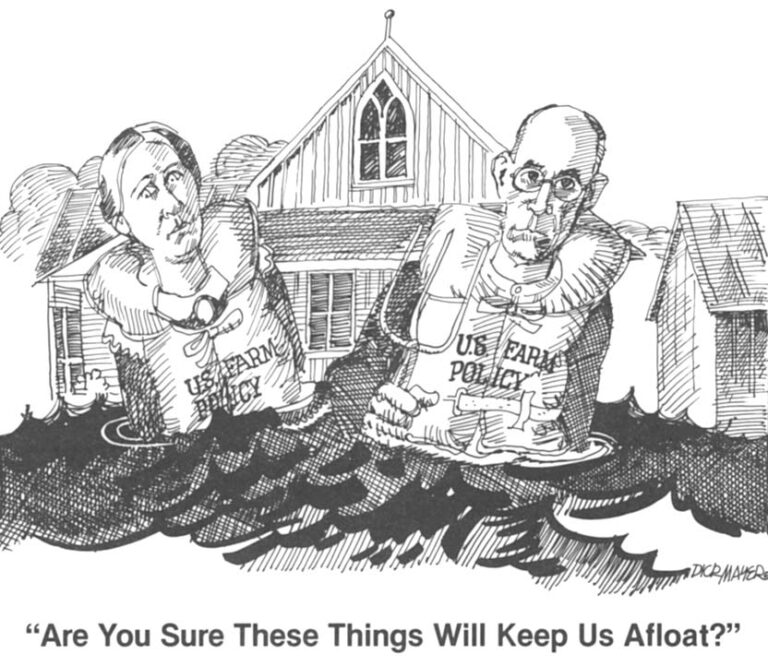

The current farm law, signed by President Carter in September 1977, is, like the 1973 law, built around target prices, crop loans and acreage restrictions. Price supports are generally higher than in the 1973 act, to combat higher farm costs. The Carter administration, proud of the act, says the act is largely responsible for increased farm income, which is expected in 1978 to exceed $25 billion. But the program is costly, and still many farmers are angry. The National Farmers Union says the parity ratio stands at 71 percent.

“Agricultural policy should be directed towards maintaining agriculture as a viable industry and not as a way of life,” a Department of Agriculture report stated a few years ago. “The number of farms or farm population size is irrelevant except as these influence performance of the agricultural industry.”

It is preposterous, to many leaders in American agriculture, to many farmers themselves, to question American agricultural policy-the policy, its friends would say, that has helped generate the stupendous amounts of food that the nation produces, the mountains of wheat and corn that, again this harvest time, fill the nation’s granaries and even in Great Plains towns, its streets. We are, many farm leaders repeatedly point out, the best fed nation in history, a nation that, despite rising food costs, spends relatively little-23 percent of private spending, by latest count-on food.

Many old farm leaders, in their graves now, would surely be amazed at the nation’s farm productivity, and at the living standard that many farmers enjoy.

But agricultural policy must be questioned. Shall farm policy goals concern themselves only, or largely, with raising farm income, as important as that is to many farmers? Shall it deal only with surpluses? With productivity? With maintaining agriculture as an industry?

Today in the United States:

-

The number of farms has declined from a high of 6.8 million in 1935 to less than 2.34 million today, according to a 1978 study by the General Accounting Office, 400,000 fewer farms than the Department of Agriculture had anticipated. The actual number of farms may be less than two million, the GAO says. By 1980, the number is expected to be under 1.5 million. Much of the decline has occurred since World War II; as late as 1950, for example, the nation has 5.5 million farms. Since 1950, the United States farms have been going out of business at the rate of 2000 per week.

-

The largest 20 percent of farms account for about 80 percent of farm sales.

-

It is likely, according to the GAO, that less than half of the nation’s farmland is owned by the operators who farm it.

-

A majority of farmers earn more money from city jobs than from their farms. In 1977, for example, the farmers’ income from farm work totaled $20.6 billion-down from a record $29 billion in 1973-compared to non-farm income of $31.4 billion. Non-farm income has exceeded farm income every year since the mid1960s, except for 1973 and 1974, the years of the Russian grain sales and high prices.

-

Only about 9 percent of American farms receive support under government commodity programs. One percent of American farmers receive nearly 29 percent of all government agricultural program payments.

-

The nation’s gigantic increases in food production have been brought about by an increase in the use of machinery and a large reliance upon chemicals- fertilizers, pesticides, fungicides, herbicides. In 1965, for example, only two percent of the tractors sold in the United States possessed more than 100 horsepower; now, about half the tractors have that horsepower; models with horsepower of 150 to 300 are common, and tractors are available between 450 and 750 horsepower. Fertilizer use has increased more than 500 percent since World War II. Insecticides have increased 1000 percent, herbicides 2000 percent.

-

The agricultural colleges, the experiment stations, the extension services, many agricultural analysts agree, benefit larger, richer farmers and industrial farm concerns, not family farmers. Agriculture writers Masie Conrat and Richard Conrat, say, “Government research facilities have designed such equipment as: automated systems for the industrial production of poultry, beef and hogs; elaborate machinery for the extensive application of fertilizers, insecticides and herbicides; mechanical harvesters for tomatoes, peaches, nuts, citrus, grapes… Not only has this high-priced equipment completely failed to meet the needs of the majority of the nation’s farmers, in many cases the development of such technology has posed a serious threat to their survival.”

Agricultural subsidy programs, dating in large measure to the parity-based programs that evolved in the 1930s, favor increased farm size and specialization. They help push people off the land, encourage investments in new technology, and aid farmers with extensive capital and large land holdings. The GAO says of these programs, including the 1977 act:

While vaguely aimed at helping the “family farmer,” (g)government assistance programs have… benefited the largest farms… Because they are geared to production, the percentage of farmers receiving government payments rises with farm size, as does the size of the payment. Government assistance programs have also become capitalized into land values, thereby benefiting larger landholders to the greatest extent.

It must be understood, too, that direct subsidies are just a part of agricultural policy. For example, tax laws encourage corporate farming, purchase of new machinery, expansion of land, and, because of tax shelter provisions, attract investments from non-farm people and institutions. Highly subsidized water projects have supported larger, more affluent farmers; the nation’s largest farms, while representing less than 14 percent of irrigated farms, control over 41 percent of the nation’s total irrigated farmland. Farm practices alter as new machinery and techniques are made available. Farmers buy more land to make the huge new machines pay. Reliance on fertilizers and other synthetic compounds locks farmers into use of petroleum-based products and saddles them with costs that will continue to increase.

Agriculture, the beneficiary of gigantic subsidies, more than many farm sector people care to admit, is more than the planting and harvesting of crops, the raising of livestock. The Department of Agriculture may decry that as romantic. It is true. Can it be denied that the nation is better off with as many farm families as possible, with adequate incomes on the land? With the most extensive areas as possible in crops? With cities contained? Since the nation’s founding-before that-we have extolled the virtues of the farm and farmers. Much of that has been words. Dramatization. People like, say, Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson, champions of the agrarian man, were the most sophisticated, the most urbane of men, city men. Peek and Johnson, it should be recalled, wished to increase farmers’ income; they also wished to increase tractor sales. Earl Butz is pilloried as the caricature of the agriculture- professor-agribusiness executive, the farmer capitalist, for his remarks, “Adapt or die,” and “farming is the survival of the fittest.” But Butz’s thoughts are no different than those of many farmers and farm leaders. He is merely more outspoken, more cheeky. We have Americanized our farms. Our farm policies have assisted that. That is the matter.

©1978 William Serrin

WILLIAM SERRIN is spending his Fellowship year reporting on farmers, food and farming.