(Chicago) — Every day, Monday through Friday, starting at 7:45 a.m., 12 men, older, white-shirted fellows, take their seats at gray, office-style desks in a converted, 100-year-old townhouse, five minutes from Michigan Avenue. They spend the next eight hours or so on old, black telephones, talking the number of calls is in dispute — to slaughterers, brokers, Meat wholesalers, and other people in the meat business. By about 3:30 p.m., perhaps with the assistance of their director, 70-year-old Lester I. Norton, they determine the closing, or final prices for beef, pork, lamb and for many animal products, including hides, oils, glands and blood. These prices are printed on eight and one-half by 14-inch sheets of yellow paper, formally called the Daily Market & News Service, but generally known as the Yellow Sheet. The publications are then rushed into the mails for first class and special delivery shipment around the country.

These men, about whose techniques little is known, men whose work is unscrutinized by the government, set the nation’s meat prices.

Used for the sale of an estimated 80 to 90 per cent of the meat sold in the United States, the Yellow Sheet is regarded, not particularly imaginatively, as the “bible” of the American meat industry. Farmers, commission men, slaughterhouses, meat wholesalers, supermarket chains, pet food companies, hide processors, insulin manufacturers, sporting good companies that purchase hides for National League Footballs or animal intestines for tennis racket strings — almost everyone who sells or purchases animals, meat or animal byproducts in the United States uses, or has his prices determined by Mr. Norton’s Yellow Sheet. It is one of the most important publications in the country.

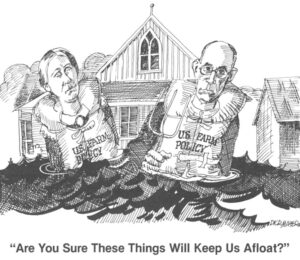

In recent months, the Yellow Sheet has become the subject of much attention in the farming and meat industries. Some 500 Middle West farmers, organized in large part by Glenn L. Freie, a farmer and cattleman, of Latimer, Iowa, have formed the Meat Price Investigators Association and, they say, spent more than $500,000 investigating beef pricing, including the techniques of the Yellow Sheet. The group has filed two law suits, now in federal court in Dallas, Texas, one against four large meat packers, another against a number of major Food Chains, the National Association of Food Chains, and the Yellow Sheet, alleging that the packers and the food chains manipulate Yellow Sheet prices to the detriment of cattle producers. The House Small Business Committee is investigating the Yellow Sheet. It has subpoenaed the reporters’ worksheets and other materials, and the committee chairman, Rep. Neal Smith, Democrat of Iowa, charges that the Yellow Sheet “fabricates a large percentage of its prices” and that the meat industry is “about as far from a free market system of transaction … as we can get.” Secretary of Agriculture Bob Bergland, announcing a Department of Agriculture investigation of meat price reporting services, including the Yellow Sheet, said, “No one really knows how the values they put on meat are arrived at This attention, particularly the tart remarks of people like Congressman Smith, vex Mr. Norton. He and his men, he says, sitting in an incredibly cluttered office, smoking one cigarette after another, arc scrupulously honest. Could the Yellow Sheet have lasted 55 years, he asks, if this were not the case? He ascribes much of the attention to high meat prices, something that for decades has brought problems to the meat industry, although he notes that last fall, when choice cattle were selling for a little more than $40 a hundred pounds, the Yellow Sheet was blamed for low cattle prices. This summer, he says, with cattle selling for $50 to $60 a hundred pounds, it is suggested that the Yellow Sheet is responsible for high meat prices. “Whenever anybody gets the least bit curious about live animal prices or meat prices,” sighs Mr. Norton, “a meat-industry Job, immediately up goes the flag and they say, ‘Let’s ask the Yellow Sheet about this and kick them around a bit.'”

Owned by the National Provisioner, Inc., which also publishes the nation’s leading meat industry magazine, The National Provisioner, the Yellow Sheet lists prices for up to 337 carcass, meat cuts and animal product items. It does not list prices paid for live animals, that is, the cattle, hogs and sheep that the nation’s farmers sell for slaughter to provide the nation’s meat. It reports only negotiated or “open-market” sales. It does not list prices of what are known as formula trades, transactions in which a purchaser — most supermarket chains buy this way — agrees to buy meat for delivery at a future date and pay the price listed on the Yellow Sheet, on the day of delivery. This is known as “buying at the sheet.” Nor, Mr. Norton says, does the Yellow Sheet report what are called distressed sales, transactions in which, say, one packinghouse must sell old meat, in danger of spoiling, without regard to prevailing prices.

Yet, although the Yellow Sheet does not report the prices paid for live animals, it indeed sets a large majority of these prices. As a farmer sits in his quiet farmhouse in, say, Iowa, Illinois or Nebraska and calls his trucker to have a load of cattle picked up, it is Mr. Norton and his reporters, in their upstairs offices amidst the people, cars and hubbub of downtown Chicago, who determine, in large part, what the farmer will receive for his investment and months of labor.

The importance of the Yellow Sheet was demonstrated one Monday a few weeks ago when Cal Clark, a cattle buyer for a major Middle West slaughtering company, Illini Beef Packers, Inc., of Joslin, Illinois, came to work at 7:30 a.m. at the Joliet, Illinois, stockyards. The day before Mr. Norton’s Yellow Sheet had listed the closing price for grade three choice beef, the kind that has great sales appeal, because of its fairly high fat content, at 87 cents a pound. So Mr. Clark was instructed by his superiors to purchase cattle at a price that would come out to no more than 90.5 cents a pound of the dressed, or carcass weight — 87 plus 3.5 cents for shipping from the packer to the meat wholesaler. At 9:10 that morning, Mr. Clark examined a group of 73 cattle raised by a northwestern Illinois farmer. He calculated that they would dress out at 63 per cent (the exact figure turned out to be 63.07 per cent). He took 63 per cent of his 90.5 cent-a-pound limit to get 57.02 cents. He subtracted .43 cents a pound to allow for the transportation costs from the stockyard to the slaughterhouse. He rounded the figure to the nearest quarter-cent, and bid 56.5 cents a pound for the live cattle.

On Wednesday, Illini Beef used the Yellow sheet again to determine the price at which it would sell the beef from the cattle that Mr. Clark had purchased. That morning Illini Beef agreed to sell a carload of beef, about 40,000 pounds, including beef from the batch that Mr. Clark had purchased, to an Eastern meat wholesaler, Richard H. Lubben & Sons of Englewood, New Jersey. The Yellow Sheet price for grade three choice beef carcasses weighing 700 to 800 pounds was again 87 cents a pound. This, plus 3.5 cents for transportation, was what Mr. Lubben paid.

When Mr. Lubben sold a carcass from Mr. Clark’s purchase, he used the Yellow Sheet price he had paid, plus his costs and profit, to set the selling price. The carcass went to a small butcher shop, B & M Market in Park Ridge in northern New Jersey, for 98 cents a pound. And when a young woman, Susan Mandell, of Montvale, New Jersey bought two pounds of ground chuck from the steer at $1.99 a pound, her price, too, was in large part determined by Mr. Norton’s Yellow Sheet, of which she had never heard.

The Yellow Sheet and The National Provisioner Magazine have for decades been important parts of the meat industry.

During the last part of the 19th century and the early part of the 20th century, the American meat industry, its power concentrated in the hands of a few packers like Swift and Armour, often worked together, many times forming pools, to set prices. Then the industry came under a series of attacks. It was investigated by the government during the great era of trust busting. An “embalmed beef” scandal broke out after the Spanish-American War; Theodore Roosevelt testified that he would rather have eaten his old hat than the beef procured by the government. In 1906, the muckraker, Upton Sinclair, published his famous novel, The Jungle, an indictment of sanitary conditions in packing houses and of working and living conditions faced by packing house workers. In 1918 the government reported that the major meat packers, Swift, Armour, Cudahy, Wilson and Morris, had engaged in a conspiracy to monopolize the industry and fix prices. And in 1921, the Packers and Stockyards Act prohibited packers from exchanging information about the price, volume or grade of livestock.

The National Provisioner, which had been founded in Chicago, in 1891, was dismayed to see the meat executives cowering before people like the socialist Sinclair and the blustering Roosevelt. The magazine’s urging led to formation in 1906 of the American Meat Packers Association, now the American Meat Institute, the meat industry’s major trade and lobby group. But the meat packers still felt their industry was in a state of confusion. Without knowing what competitors were paying, the industry executives said, how could you know what to pay yourself? The frustrated packers asked the National Provisioner Company to start reporting meat prices. The first Yellow Sheet was published in October 1923. Since then, says the proud Mr. Norton, who has been with the Yellow Sheet throughout its publication, it has never missed an issue.

It is this long-time closeness to the meat packers, plus the reporting methods, that bring criticism of Mr. Norton and his Yellow Sheet.

Critics say that because the Yellow Sheet does not report formula sales, only open market or negotiated sales, it uses only a small part of meat sales as the basis for industry-wide prices. Today, in contrast to the early days of the industry, it is estimated that 75 to 90 per cent of the perhaps $40 billion worth of meat sold in America annually is purchased under formula sales, leaving only 15 per cent for negotiated sales. The House committee’s chief investigator, Nick Wultich, a former FBI agent, says that during the 25 days of his investigation, the Yellow Sheet based its prices on only 3.8 per cent of the nation’s beef sales and 4.4 per cent of pork sales. For that period, Mr. Wultich says, 90 per cent of the Yellow Sheet prices reported were not supported by the reporters’ worksheets and 74.9 per cent were based on no trades. Mr. Wultich charges that the Yellow Sheet instead of “admitting that the number of negotiated trades has . . . been drastically reduced . . . has fabricated the daily sheets and attempted to show the meat trade that it’s still performing its job.”

Critics say that the Yellow Sheet is susceptible to perhaps a dozen methods of manipulation. A packer, for example, could sell a shipment of beef to another packer, a friend, at just above the current price, say 90 cents instead of 87 cents a pound. The higher figure would be reported to Mr. Norton’s reporters at the Yellow Sheet, which might then list the 90-cent price as the closing price for the day. If the first packer had a large amount of meat to sell the next day, he could then sell it at 90 cents-and turn a three-cent profit. Or a packer could split a load of meat, selling half at three cents below the current price and half of three cents above. The cost to the buyer would be the same. But the higher price could be reported to the Yellow Sheet, be used as the Yellow Sheet price for that day, and enable the packer to sell a large amount of meat to other buyers at the higher-price.

Mr. Freie, the MPIA leader, charges that the Yellow Sheet is a “tool for the packers and supermarkets.” He charges, for example, that the Yellow Sheet reports distressed sales, thus unfairly lowering the market price. Manipulation of the publication, he contends, costs American farmers billions of dollars each year. “There is no legal nor mandatory requirements to report all sales,” Mr. Freie says. “So naturally, the packers and supermarkets may report only those sales which are advantageous to them, and probably detrimental to cattlemen.”

A central question is this: How do Mr. Norton and the Yellow Sheet reporters determine “closing” prices? The livestock market is not like the financial stock market; there is no central exchange, no exact starting and stopping times. Mr. Norton and the Yellow Sheet reporters make what he describes as several hundred calls throughout the United States to determine market prices. He declines to reveal the “act number of calls his men make. But, given the number of items the Yellow Sheet lists, even under his estimate, little doubt exists that the reports are often based on a small number of sales. At the end of the trading day, the Yellow Sheet reporters determine what they believe to be the final price. Mr. Norton says “no room for opinion” exists in setting the price. But he says some late sales may be disregarded because they represent what he considers special circumstances. And when several end-of-the-day prices exist for the same item, only one can be chosen, and Mr. Norton’s reporters select it.

A number of reforms have been proposed to insure Cattlemen that meat prices are fair and to protect consumers against the increased prices that fraud can bring. Some critics want formula pricing eliminated. Mr. Freie’s MPIA has called for mandatory reporting of all sales of meat and meat products with criminal penalties for false reports. The MPIA also proposes electronic meat marketing boards that would provide what Mr. Freie calls an “anonymous offer and bid system” across the nation. Congressman Smith, in his report, which is expected in September or early October, is expected to propose reforms. And a meat pricing reform act already introduced before Congress, would establish heavy penalties for false sales reports and would require that packer-to-packer sales suspected of being a means of price manipulation, be reported separately, not with regular packer-to-supermarket sales.

But reforms generally are slow in coming and often disappointing. Farmers, Mr. Freie notes, are great optimists; they grouse when prices are low, but when prices are high, they forget bad times and seem to assume that high prices will last forever. Eighty years ago, an agriculture reformer, Mary E. Lease, said farmers should raise less corn and more hell. The truth is that farmers almost always have raised more corn than hell, and probably will continue to do so. And congressional reforms have a way of gaining headlines, but bringing little change. Mr. Wultich, the investigator, said a number of farm and meat industry people with complaints against the Yellow Sheet refuse to make their names public, believing that the Yellow Sheet hearings will come to little, and they would be left with reputations in the meat industry as turncoats. The crusty, aggressive Mr. Norton, sitting behind his desk in Chicago, wondering, fie says, what he did to deserve such enemies — unsophisticated farmer reformers, cocksure ex-FBI agents, headline- seeking congressmen — says, “We get used to criticism. It doesn’t bother us a damn bit. All that any of these things every do is to increase our circulation.”

©1978 William Serrin

William Serrin is spending his fellowship year writing about ” Farmers, Food and Farming.”