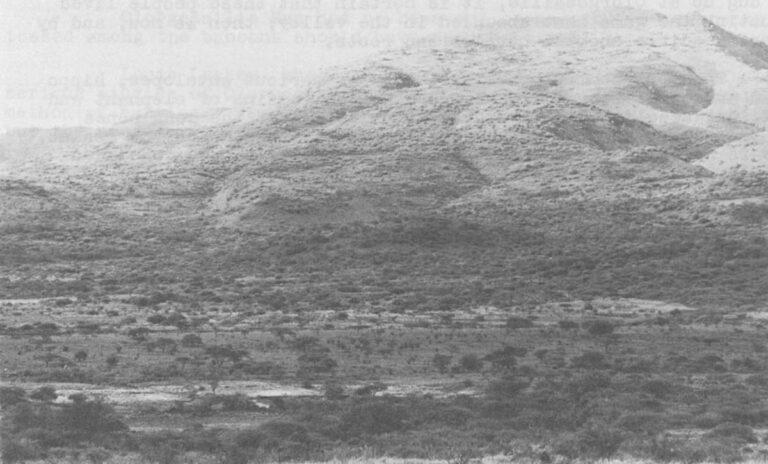

It is a wild and rugged place — hot, dry, uninhabited most of the year and then only by wandering Masai herdsmen tending their ragged cattle.

It is called Olorgesailie and it is 100 miles south of the Equator on the floor of Kenya’s Rift Valley, where the earth’s crust cracked open millions of years ago. Ever since, earthquakes have tossed the still widening and subsiding valley floor into a wrinkled and broken landscape.

Commanding the scene, five miles to the south, is Mt. Olorgesailie, a dormant volcano peaking half a mile above the valley floor. Fifteen miles to the east is the wall of the Rift Valley, a precipitous escarpment rising nearly 3,000 feet to the flat, more typical East African plains beyond.

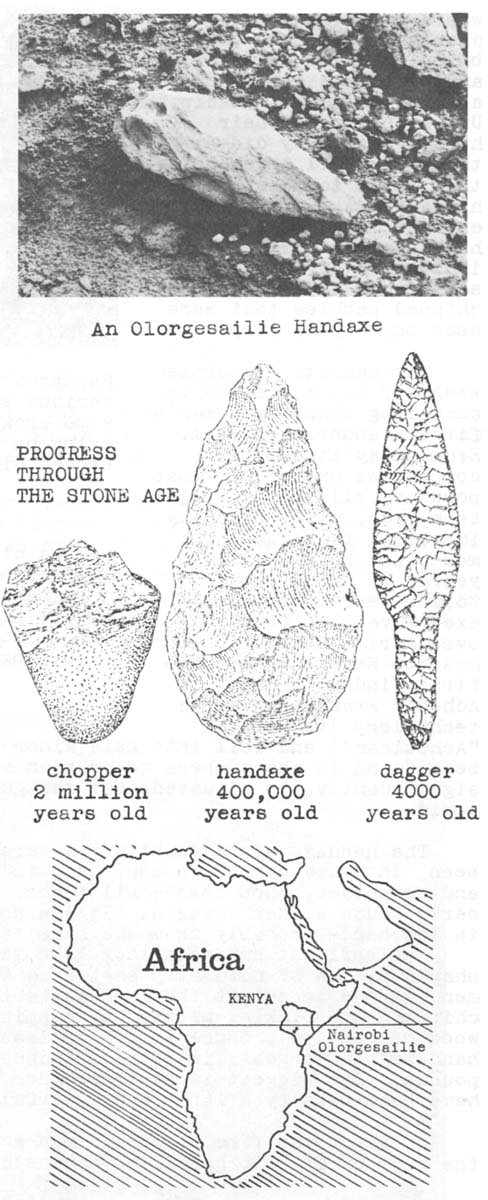

Here, along one of the gentler slopes of the valley, the infrequent rains have for decades been delicately washing away the soil to expose one of the most remarkable displays of the technology of early man to be found anywhere. Here, lying on the surface of the ground, unrecognized until the 1940s, are hundreds of stone handaxes — multi-purpose cutting and whittling tools — carefully hewn by a race of people who stood very close, in the evolutionary sequence, to the earliest members of our own species. They lived perhaps 400,000 years ago and, if a sense of esthetics is any criterion of humanness, they were among the creatures who crossed the last great bridge from brutish hominid to feeling, sensitive human being.

Because no bones of Olorgesailie Man have yet been found, he cannot be judged by the prominence of his brow ridges or the thickness of his skull. All we have to go on is his craftsmanship — the unmistakable fact, virtually ignored by anthropologists, that some of the handaxes he fashioned are shaped more regularly and symmetrically — more beautifully — than would have been necessary to produce an efficient and practical tool.

Most of the handaxes to be seen at Olorgesailie — where much of the material unearthed by archeologists has been allowed to remain as found — are irregular and lopsided, but clearly would be effective as cutters and choppers or even stabbers and slicers. A few, however, are more artfully sculptured. Care has been taken to flake away bits of stone so that edges are straight or gracefully curved. The proportions are quite pleasing, even to an eye schooled in Brancusi or Calder.

So, nearly half a million years ago, there was a people beginning to display what could only be called a sense of art and, it seems reasonable, a pride of craftsmanship. Until they made their handaxes as they did — that is, until a few of them chose to make their handaxes as they did — earlier men and pre-men had shown no more indication of an esthetic sense than to make crudely chipped pebbles that were used to chop up prey.

The handaxe, a pointed wedge of stone chipped to an oblong shape, was man’s first standardized tool. Even today it can be counted as one of his most popular, billions having been made, with gradually improving technique, for more than half a million years, up until about 75,000 years ago. Handaxes have been found all over Africa, throughout most of Europe (where the first finds, in Saint Acheul, France, gave the technology its name, “Acheulean”) and well into Asia Minor and India. But nowhere have they been found in the numbers to be seen at Olorgesailie, which, perhaps significantly, is situated near the geographic center of the Acheulean world.

The handaxe was undoubtedly a versatile tool. It can, and has been, in tests by modern men, used to cut up an animal carcass, dress and cut hides, chop down small trees, whittle poles and spears and carve crude wooden vessels. It was not hafted to a handle but held in the hand — probably from the side, to use as a knife.

The earliest handaxes look like little more than fortuitously shaped pieces of naturally shattered stone. Gradually, however, early men learned to select the more suitable minerals and to control the chipping and flaking process by rapping the stone with a cylinder of wood or bone to produce a more or less consistent shape. The average handaxe at Olorgesailie is nine inches long and weighs three and a half pounds. The biggest is a six pounder that is 13 inches long and must have been used by a large and powerful man.

At about the time primitive men were camping in small bands around the foot of Mt. Olorgesailie, the esthetic dimension of creativity appeared — probably not at Olorgesailie itself but at some other place like it and at a similar stage of evolution. Man sought for the first time to transform an abstract ideal into the concrete, at least in a material that would survive until today. The material world was made not only more useful and comfortable but more beautiful.

Most anthropologists consider that art did not truly come into being until the time of cave paintings some 370,000 years after Olorgesailie. Yet, it should be clear from the ancient handaxes that the artistic impulse that would create those magnificent and artistically mature paintings in European eaves was already beginning to glimmer among man’s beetle-browed and nearly chinless African ancestors.

Back then Olorgesailie was a different world. Although the volcanoes, then still active, rumbled and smoked, it was mostly peaceful by the shores of a wide lake that has long since dried up. Judging by fossil pollens found at the site, the lake was surrounded by swampy areas that receded into low scrub and trees along tributary streams . Away from the lake the valley was, as East Africa generally is today, open savannah, grassland with patches of low bush and lacy trees.

There were antelopes not greatly different from those of today, and warthogs, zebras and hippos. There were proto-giraffes with flat, moose-style horns. Giant wild pigs, as big as a modern hippo, rooted among the trees. Troops of giant baboons the size of bears dominated the few rocky high spots. Lions, sabre-toothed tigers and an ancestral elephant with downward curving tusks also lived around the lake.

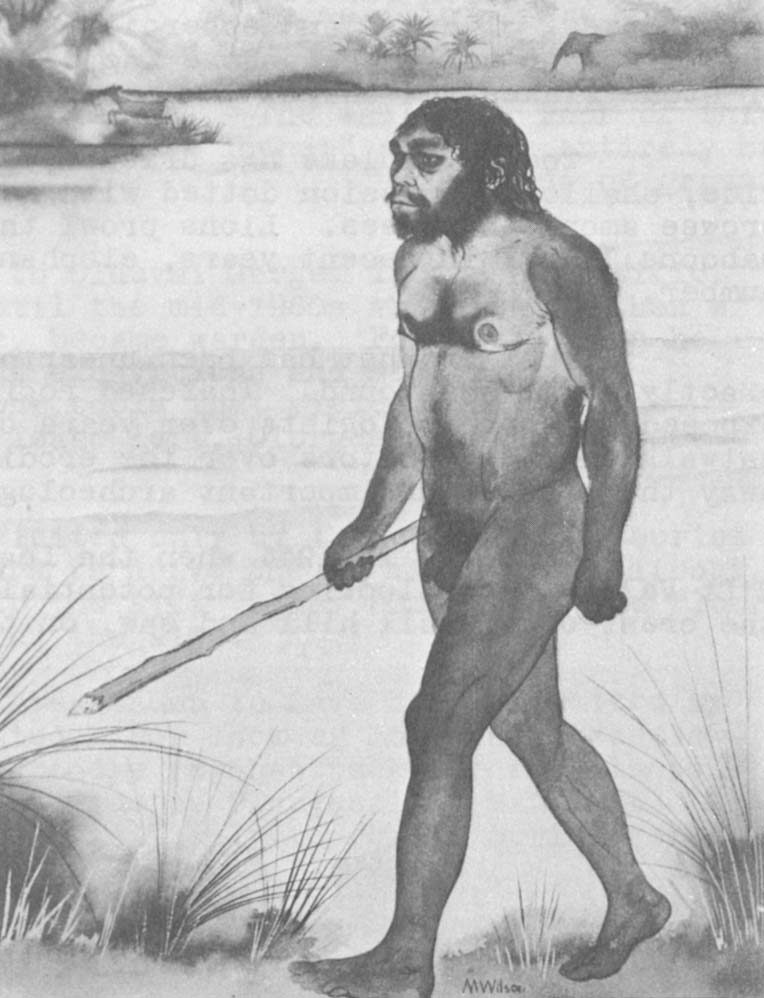

And along the sandy banks of the streams that ran into the lake there lived the makers of the handaxes, probably Homo erectus — men and women of the same genus as we, but of an earlier species with a brain only three-quarters as big.

Imagine you are on one of the foothills of Mt. Olorgesailie with a pair of binoculars. About a mile or so away from the lake, near a long row of flat-topped Acacias that line a stream, there are moving forms — naked, dark people. One, a female, is squatting, and scratching at the ground with a stick. Now and again she picks up something and pops it into her mouth. A male is walking, quite erect, heading for a low rockpile where two others sit straight-legged on the ground. With the left hand they are holding stones against their left thighs and hammering them with what appear to be sticks or bones. The ground is littered with rock chips. Back, in the shade of a large tree, three little ones play under the watchful eye of another adult, a female.

From this distance they look like ordinary people and, from the neck down — judging by the bones of Homo erectus found in other parts of the world — they are virtually indistinguishable from us.

Homo erectus as he might have looked at Olorgesailie. (Artists’ conceptions and misconceptions of the appearance of early men often vary even though all are mentally fleshing out the same bones. Compare this version of H. erectus, by a British Museum artist, with that on page two by an artist at Time-Life Books.)

Their heads, however, are rather different. With a low forehead, a heavy brow ridge shading the eyes, a flattish nose and week-chinned jaws jutting forward, they are definitely not like us.

Because the earliest known agriculture did not begin until some 10,000 years ago, and from the ancient animal bones scientists have dug up at Olorgesailie, it is certain that these people lived by hunting the game that abounded in the valley, then as now, and by gathering edible shoots, berries and roots.

The most common bones are those of various antelopes, hippo and an ancestral zebra. There are also the remains of elephant and an extinct species of wild pig. Virtually all of the long bones have been split for the marrow and the skulls bashed for the brains. There is no evidence of fire, and some authorities have concluded that Olorgesailie Man ate his food raw. One expert, however, has argued that ashes do not preserve well in this part of the world and that no judgement can be made.

On one occupation floor exposed by carefully lifting away the overlying soil, archeologists have found a large number of baboon bones, enough to indicate that a minimum of 63 adults and juveniles were butchered and eaten at this place.

Dr. Glynn L. Isaac, before joining the faculty at Berkeley, spent four years excavating and studying Olorgesailie in the 1960s. He has raised the possibility that the large number of baboon remains, correlating in age and sex distribution with living baboon troops today, may represent not the accumulation of many successful hunting trips, but the single massacre of an entire troop.

Even today, Isaac said, the Hadza people of northern Tanzania occasionally band together at night to surround a sleeping baboon troop. The Hadza then shoot a few arrows into their midst and club the frightened monkeys to death as they attempt to break out of the trap.

Olorgesailie Man had no bows and arrows, but a few rocks tossed among the baboons should have served as well.

Louis Leakey, who with his wife Mary conducted the first serious studies of Olorgesailie some 30 years ago, suggested another method of hunting. Few other authorities accept the interpretation, but the speculation is intriguing in any event.

Among the many handaxes, cleavers (chopping tools with flat rather than pointed edges), and rocky debris, Leakey also found what he considered to be clusters of three nearly spherical stones two to three inches in diameter. Cobblestones and spheroids are common at Olorgesailie and other sites of the same vintage. They are generally thought to be pounders for mashing up tough roots and seeds or bashers for opening bones and skulls. Some speculate they were even missiles for warding off wild animals. (Olorgesailie Man was prey as well as predator.)

Leakey contended the 13 groups of three stones that he found were the remains of bolases. The bolas, a weapon now used only by some South American Indians and some Eskimos, consists of three spherical stones tethered to a single knot. The bolas is swung around the head and let fly at the legs of the hunted animal, entangling them and bringing him down.

If Olorgesailie man had invented the bolas, a relatively sophisticated device, the leather pouches and thongs would have long since rotted away to leave three closely spaced spherical stones. Similar evidence for the bolas has not been found in any other prehistoric site of comparable age. Most authorities consider the spatial arrangements of the “bolas stones” coincidental or less. Picking out the spheroid trios from all the single round stones is about like finding constellations among the stars.

There is, however, an intriguing other fact. Although no modern African tribe is known to use the bolas for hunting, some groups in nearby Uganda and Tanzania have a “bolas and hoop” children’s game. The object is to bring down a rolling hoop with a bolas of three little pebbles. There is also a “spear and hoop” game that young boys play to learn an important hunting skill. Could the “bolas and hoop” game have survived from its days as a training method even after adult hunters switched to superior stone-tipped spears?

A more probable method of hunting was to drive the animals into soft ground, perhaps the marshes around Lake Olorgesailie, and to club or stone them to death as the animals wallowed hopelessly in the mud. At Olduvai Gorge, 120 miles to the south, Leakey found the intact leg bones of some animals standing vertically in the now solidified mud, suggesting that the game became stuck in the swamps and were killed and butchered down to the mudline. In Spain, Clark Howell, another Berkeley anthropologist, has found the intact right half of an elephant at a Homo erectus site. He suggests that about the only way an elephant could lose only its left half would be if the ancient hunters drove it into a bog where it was killed and fell, embedding its right side. The bones of the left side are probably to be found, disjointed and smashed open, at some nearby, still-buried feasting site.

At Olorgesailie scientists have located what appears to be a hippo butchery. Most of the bones of a single hippo were found there, left in just the state and with just enough handaxes nearby to suggest that the hunters either killed and cut up the hippo on the spot or found him there already dead.

This raises one of the least appealing interpretations of the life of early man. Though, doubtless, they sought their protein on the hoof, it is entirely reasonable that they would not turn down several hundred pounds of meat if they found it already dead. Our ancestors were probably carrion eaters, scavengers, competing with the vultures and hyenas for food.

It may have been, however, that man did not always have to compete for the same dead animals. With the invention of the handaxe, he would have been able to fill an ecological niche theretofore vacant. The hide of elephants and hippos is too tough for ordinary scavengers to break through. When the beasts die (they have few natural enemies), the worms usually take them. With his surprisingly sharp handaxe, however, Olorgesailie Man would have had no trouble hacking his way into a dead pachyderm.

Like the hunter-gatherer peoples of today, Olorgesailie Man undoubtedly ate a greater variety of foods than industrialized peoples who depend on a few domesticated species. The Rift Valley was abundant with game and, contrary to stereotype, the life of prehistoric man was probably not one of privation and hardship. Some studies of the Hadza and the Bushmen of the Kalihari, both hunting and gathering peoples, show that the adult male hunters can meet the food needs of their families in less than 20 percent of their waking hours. The bulk of the day is spent in leisure and in crafting new tools. The women, traditionally the gatherers, can find all the vegetables their families need in less than half a day.

“It is probable,” Isaac says, “that the widespread notion that early paleolithic life was filled with deprivation and the need for continuous questing after food is erroneous.”

For all the bones that have been found at Olorgesailie, none have belonged to the human beings themselves. This contrasts with the situation at many other Acheulean sites and suggests that the dead were removed, perhaps to an open field for scavengers. This is the practice with some modern African tribes, who consider it a far more civilized and natural way of dealing with the dead than preserving corpses. Almost certainly the dead at Olorgesailie were not buried, a custom that did not appear until about 40,000 or 50,000 years ago.

The lack of human remains also suggests that cannibalism was not a significant practice. Elsewhere, in human cultures dating up to modern times, the split and cooked bones of men have been clear evidence of cannibalism.

From the size of the occupation floors that have been found at Olorgesailie and from the quantities of worked stone, it is possible to deduce that bands of two different sizes lived there. The smaller was about four or five people, probably a nuclear family, while the larger comprised about 25 to 30 individuals, perhaps several families. Most of the sites appear to have been occupied for at least a few months. The people appear to have moved away from time to time, perhaps to follow migrating herds. Slight differences in stoneworking style suggest that different groups with characteristic patterns of craftsmanship used the area at one time or another.

Over tens of thousands of years, changes in climate caused Lake Olorgesailie to fluctuate, first shrinking in diameter and then expanding to flood areas that were situated a mile or more from its earlier shores. When the water was high, aquatic sediments slowly buried the flooded occupation floors, handaxes and all. Then, as the lake gradually receded over many thousands of years, new sandy beaches were created over the buried handaxes. New bands of hunters moved in and, in some cases, set up housekeeping only a foot or two above the artifacts and garbage heaps of their predecessors.

Again and again the lake expanded and contracted, creating layer upon layer of alternating beach and bottom sediment. From time to time volcanoes showered ash on the area, further burying and preserving whatever was there.

In an area little bigger than a football field, no fewer than 14 occupation floors have been found, one containing over a ton of handaxes, cleavers and spheroids. In one place there was even what might be called a handaxe factory, judging by the high proportion of stone flakes and chips, the waste of manufacturing the implements.

Today the lake has dried up completely, leaving only a wide, shallow depression dotted with Acacias and Comiphoras. Giraffes browse among the trees. Lions prowl the grassland. Leopards stalk baboons. And, in recent years, elephants have appeared in fair number.

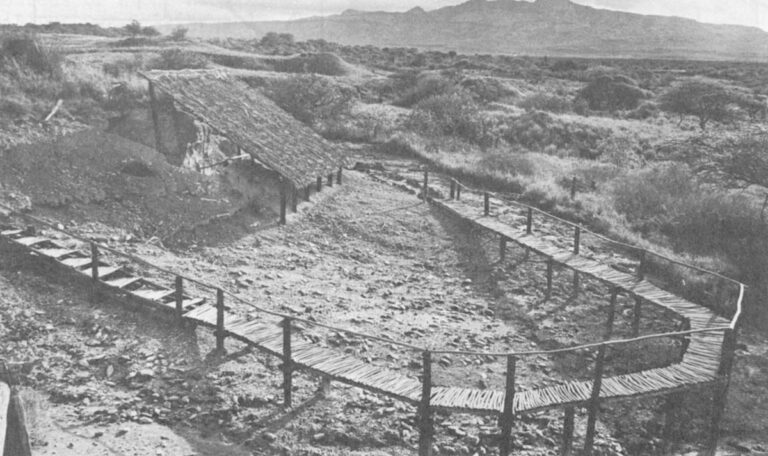

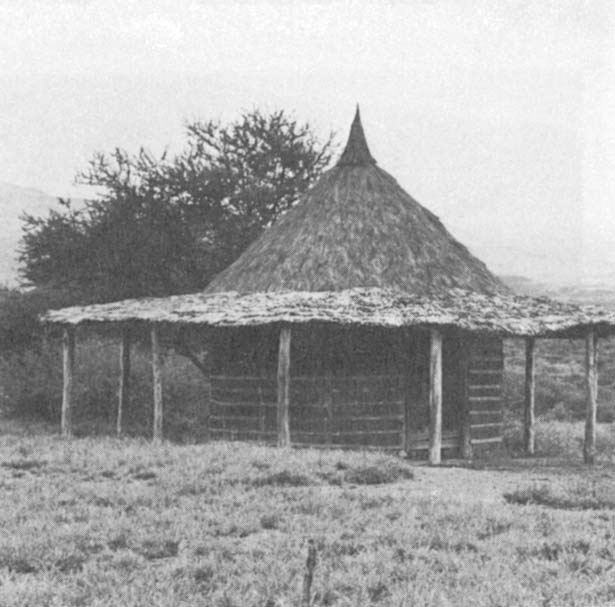

Most of what has been unearthed at Olorgesailie remains exactly as it was found. Thatched roofs protect the occupation floors exposed by anthropologists over years of excavation. A rickety catwalk carries visitors over the eroding hillside that first gave away the area as an important archeological site.

That was in 1944 when the Leakeys were tramping over the Rift Valley floor looking for potential sites. Mary Leakey reached the crest of a small hill and saw, on the eroding downside, hundreds of handaxes lying on the surface. Higher up on the slope, a few were jutting out of the bank, still partly resting on the floor where they were dropped some 400,000 years earlier. The next hard rain might wash them out.

With little money and the wartime rationing of supplies, the Leakeys could work the site only on weekends. Later they were assisted by three Italian prisoners of war being held by the British in what was then Kenya Colony.

In 1947 a council of Masai elders was persuaded to give a 52-acre area containing the sites to the government. It became the smallest and most unusual of Kenya’s national parks. The first warden was one of the Italian POWs who returned from Italy to take up his post. More recently the area’s status has been changed from National Park to National Monument.

After the Leakeys went on to Olduvai Gorge, little scientific effort was put into the site until the mid-1960s when Isaac, then a doctoral candidate at Cambridge, became warden. For four years he conducted extremely detailed new excavations and made rigorous statistical analysis of the stone tools that yielded many of the current interpretations. When Isaac left, Olorgesailie again became scientifically dormant.

And so it remains today, visited only by the occasional tourist who doesn’t mind taking two hours to drive the 40 miles from Nairobi, bumping down the rocky road into the Rift Valley and across the floor, fording seasonal streams to reach the site.

Only five percent of the area known to have been inhabited by prehistoric man has been excavated. For lack of money and because the hottest area of anthropology today reaches back for fossils ten times as old, 95 percent of the evidence Olorgesailie Man left including, perhaps, his own bones, is likely to remain buried for at least a few more years.

Received in New York on May 17, 1973

©1973 Boyce Rensberger

Boyce Rensberger, a freelance writer, is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner with support from the L.S.B. Leakey Foundation. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Rensberger, the Alicia Patterson Foundation, and the L.S.B. Leakey Foundation.