It is 5:30 in the morning and, looking east, I can see the darkness lifting over the distant rim of the wide Ngorongoro Crater. The hyenas have stopped whooping in the gorge — Olduvai Gorge — that falls away at my feet. The wind whistles through thorn bushes along my edge of this great ravine.

It is cool and strangely quiet. The starry sky will soon be ablaze with equatorial heat. But, in this fragile dawn between primeval night and reassuring day, the bones that lie buried here seem to stir.

Was it like this a million years ago — or two million — when those little ragged bands of almost-men roamed this place? Were they up and about before dawn, bustling even now under that distant tree, preparing to go out and dig roots before it gets too hot or readying to kill a gazelle? Or did they, knowing this place better, stay safely inside their rude huts of thorn branches until the heat and light drove away the predators?

The sun is higher now and light slants into the chasm, throwing the cut-away layers of geology into sharp shadowed relief. The prehistoric spirits return to their stony graves. I am standing just above Bed IV, on deposits laid down between a third and a half a million years ago. Farther down are Beds III, Il and I, the lowest stratum lying on a layer of black lava 300 feet below me that cooled nearly two million years ago.

Olduvai Gorge is probably the most famous place in the world to have yielded the remains of early man. And Louis and Mary Leakey, the husband-wife team which began excavating fossils in the gorge in 1931, are undoubtedly the best known hominid paleontologists. Louis Leakey died last year but his widow continues the search, steadily turning up more and more clues about how man evolved.

Although often described as a kind of Grand Canyon, Olduvai Gorge is really no where as spectacular. It is some 25 miles long but only 350 feet at its deepest. Dozens of tourists, shuttling between Ngorongoro Crater and the Serengeti, visit the gorge daily, driving easily into it and along the bottom in their Volkswagen Microbuses. There is an excellent little museum at the gorge and several of the sites of important discoveries are marked with plaques.

Now a dry and inhospitable place, the Olduvai area once had a lake at least 12 miles in diameter fed by streams from nearby mountains. Early hominids apparently preferred to live along the streams and the lakeshore for it is near the now dry and buried beaches and stream channels that the most productive fossil sties have been found. Over hundreds of thousands of years the lake grew and shrank, intermittently burying dry land in aquatic sediments that preserved bones.

Over the last 14 years the Leakeys have uncovered a remarkable variety of objects preserved from those distant times. There have been not only the bones of hominids and the stone tools they made but actual living floors strewn with the refuse of family groups. In one place they found what can only be fossilized hominid dung, containing a number of crushed tiny bones of lizards and other small creatures that must have been eaten whole. They found a circle of stones that is believed to have been the foundation of a hut. It is the earliest known man-made structure. And, in just the last year or so, they have uncovered a land surface more than 700,000 years old with a number of scooped out pits connected by narrow channels. It was clearly made by early men but its use remains a total mystery.

Diagrams and sketches are from Volume 3 of the Olduvai Gorge series, by M. D. Leakey, published by the Cambridge University Press.

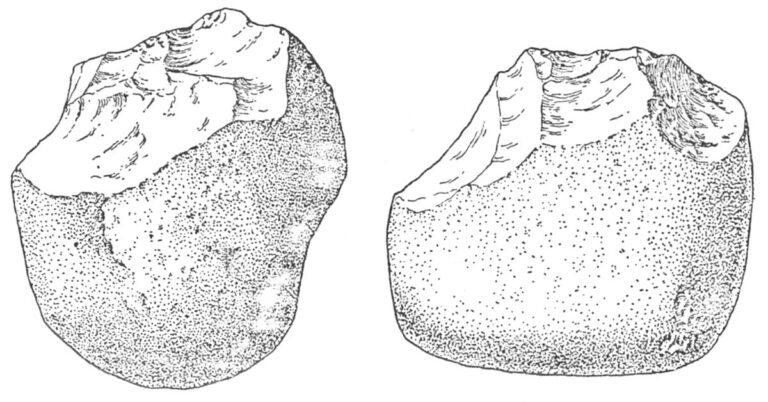

Two “choppers” found in the oldest layers of Olduvai Gorge. They were made from chunks of lava worn smooth by rolling along an ancient river bottom. These tools, among the most primitive made by early man, are shown at almost full size.

One of the most remarkable clues to the life style of early man at Olduvai is a circle of stones that Mary Leakey considers to be the remains of a hut of branches anchored at the base by the stones. It is about 14 feet in diameter and, at about 1.8 million years, is the oldest known man-made structure. No others like it are known. This is a plan of the excavation that also revealed a living floor with stone tools and bones of animals killed for food.

Although it is not the richest source of hominid bones, the wealth of other objects found make Olduvai the world’s most informative early man site. It was only after 18 years of digging in obscurity, however, that the Leakeys’ first break came.

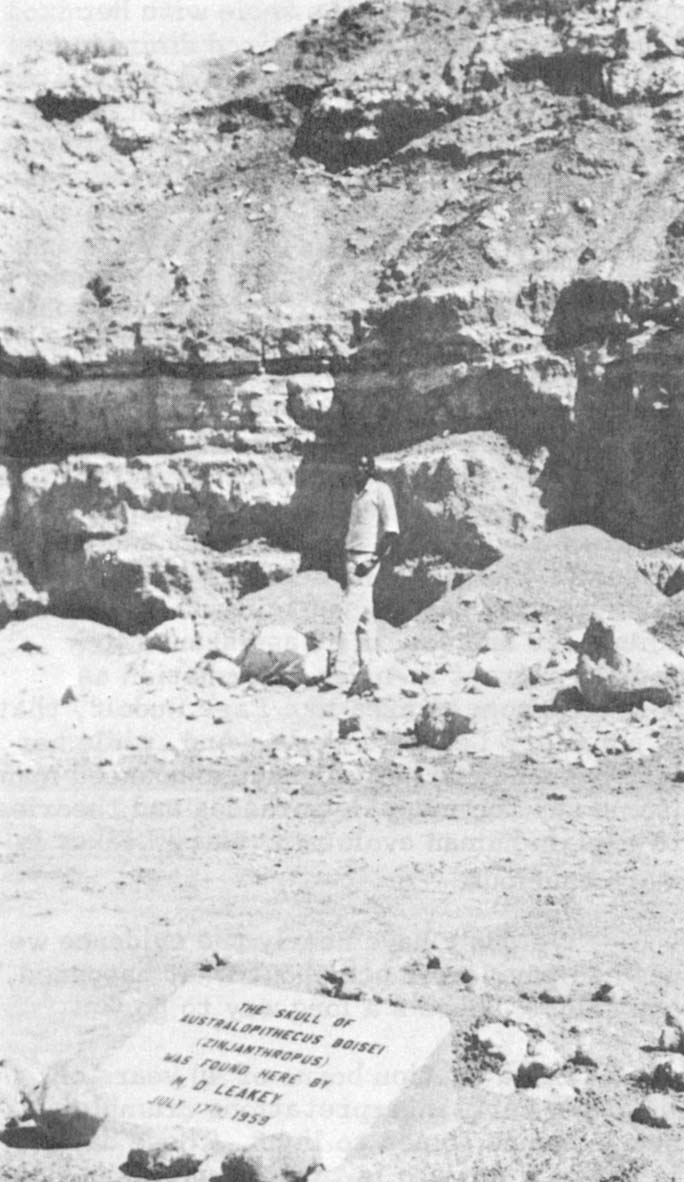

In 1959 they astounded the scientific world with the announcement that a kind of ape-man whose skull they had found was making stone tools 1.75 million years ago. Geologists had earlier estimated the age of the tools at half that but there could be no doubting the earlier date for it was based on a newly developed method that reliably measures how long certain chemical reactions have been progressing in a rock since it was formed. The skull and the stone tools found in the same layer were the first pre-Homo hominid remains to be dated from anywhere. The South African Australopithecines had been known for 25 years but they remain, even now, unreliably dated. Because the skull was markedly more massive than the South African ape-men, the Leakeys gave the creature a new name: Zinjanthropus (Zinj being an old Arab word for East Africa). Later study has led to the opinion that Zinjanthropus should be considered simply a big-boned or more robust species of Australopithecus. The old name has been dropped except as a sentimental reference to that first Olduvai skull.

Until 1959 this was a hill, sloping from the top of the picture down to the marker at the bottom. Poking through the hillside was the skull of an ape-man the Leakeys first called Zinjanthropus. To learn who he was, the hill was dug away to find hundreds of bones and stone tools. This discovery began the modern era of careful scientific study of man’s evolution.

“I regard the discovery of Zinj,” the American anthropologist Clark Howell once remarked, “as the event that opened the present modern era of the truly scientific study of the evolution of man.”

The unusually well preserved skull (broken to bits but skillfully pieced together again) with an absolute date based on solid geochemistry forced everyone in the anthropological community and a fair number outside to stare long and hard into the face of Zinjanthropus. Long before man had developed his big brain, an incredible 1.75 million years ago, he was already selecting suitable raw materials and fashioning them into stone tools — sharp-edged choppers that could cut down a tree or butcher an antelope. Human culture began almost before man did. The possible implications were staggering: man did not produce culture; culture produced man. (This crucial idea will be developed in a later newsletter).

Not long after Zinj, however, the Leakeys discovered another kind of hominid in the same level. He was a somewhat bigger brained form with anatomic features more like our own. Surely, they concluded, the tools must have been made by the more advanced hominid. Louis Leakey said he had erred in attributing the tools to Zinj and that he now felt they were part of the culture of the bigger brained but smaller, more delicately boned creature that must have been Zinj’s contemporary. Although most authorities at first disagreed with the opinion of Louis Leakey and South Africa’s Phillip Tobias that this smaller creature should be considered Homo, many have now accepted the idea that he was indeed true man, Homo. He is now generally called Homo habilis, habilis meaning handy or able.

His tools are today known as part of the Oldowan culture, named for the gorge although they have since been found in other parts of Africa. The basic Oldowan tool is called a chopper or pebble tool. It is crude enough that with a little practice almost any modern man can make one for himself. All you need is a smooth, round, fist-sized, stone — a cobblestone of the kind found in river beds. Whack it against another rock until a chunk splits off. Then whack the other side until another chunk breaks off so that the two broken faces intersect, forming a jagged edge. You have just made an Oldowan chopper in more or less the same way your ancestors did nearly two million years ago.

Oldowan Man also made a few other kinds of tools. His tool kit (a serious term used by archeologists) included stones flaked in different ways to make what have been categorized as five different kinds of choppers; scrapers that can be classed as light duty, heavy duty, side scrapers and hollow scrapers; spheroids; discoids (shaped like an overfat hamburger patty); irregularly shaped polyhedrons; burins; light duty flakes; anvils; and hammerstones. Although the precise use of the tools can only be guessed at, it seems evident that when we had a brain less than half a big as we have today, we were already well on the road to a complex life style dependent on the skilled use of a variety of manufactured tools.

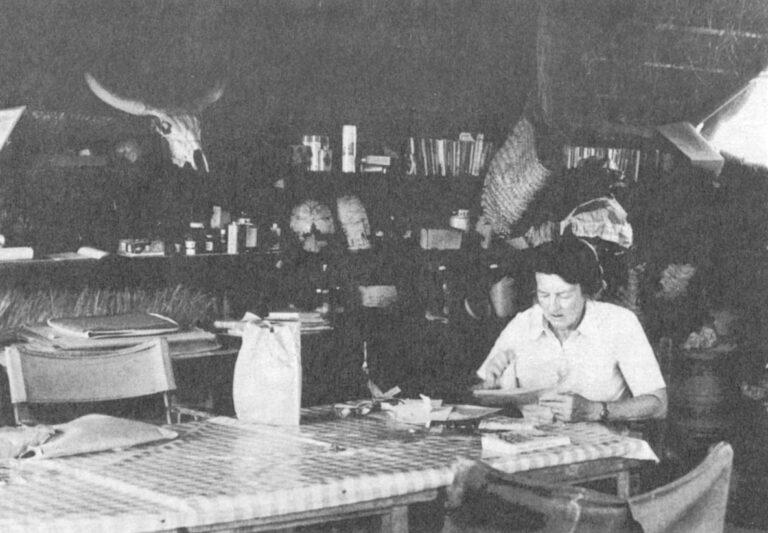

That, for Dr. Mary Leakey, is a more sensible way of defining man than the contour of the jaw or the shape of the teeth. “I think that if you find stone tools consistently associated with a hominid, then he’s a man. Culture is what really sets us apart,” she said one evening after dinner at the Olduvai camp.

It was dark and in the hissing glare of a gas lantern Mary Leakey was relaxing with her coffee at the end of a long but relatively quiet day at Olduvai. At table with her in the grass-roofed, dirt-floored dining hut were only a volunteer worker and one visitor. Two days earlier a French expert on fossil pollen who works with the Omo scientific team had left after collecting samples for evidence of ancient vegetation.

“I don’t like to have too many people around, ” the world authority on stone tools said. “Things get out of hand. I’d rather do it right. There’s no big hurry. “

Indeed, Olduvai has already held its secrets for a million years or so and there is no special urgency, she feels, to find all the answers now. While the curiosity and drive of some, like her son Richard Leakey, lead to organizing vast expeditions of 25 or more scientists and dozens of assistants to rapidly extract as much information as possible from an area like East Rudolf, that is not Mary Leakey’s style. And, while her late husband and her son have announced many (some say too many) hypotheses and theories to explain human evolution, Mary Leakey is more cautious.

“We don’t have nearly the evidence we need to say very much about what happened,” she said. “There’s a long way to go.”

It is a caution borne of 40 years of watching early interpretations crumble as new evidence comes to light. These days it is her own son who is turning up the unexpected puzzlers and turning them up almost faster than new theories can be made to account for them.

Despite the publicity attracted by Louis Leakey, who had a remarkable flair for showmanship, Olduvai in recent years has reflected the more subdued, more cautious and deliberate style of Mary Leakey. It was she who found Zinj. It was she whose analysis of the stone tools yielded today’s understanding of them. And, long before Louis died, it was already she who was really in charge at Olduvai.

Unlike some of the other Leakeys, she is not fond of publicity. Once, when she heard that a writer with an assignment from Playboy was coming to the gorge for an interview, she fled, actually driving to a nearby village for the day until she was sure the man had left. A few months later a copy of Playboy arrived at the camp sent by a friend, and the cigar-smoking, bourbon drinking lady was horrified to see that she was mentioned in the magazine after all.

“I just don’t think this is the proper place to present science,” she remarked. The article contained numerous factual errors and she said it reinforced her view, shared by many scientists, that the popular press rarely gets science right.

Although Olduvai is only a half day’s drive from her home in Nairobi, Mary Leakey spends most of her time at the gorge. She lives in a one-room cylindrical tin house, not unlike a grain bin, with a grass roof. The camp also includes two smaller houses for visiting scientists, and a lab — the most substantial building in the camp — housing trays of fossils and stone tools and work tables.

These days Mary Leakey is trying to wind down the excavations in the gorge, eventually to stop them temporarily so she can catch up on writing about the findings and so that the African workers can be put to building her a more substantial house at the camp, “one with a real floor in it.”

Once or twice a day, when an excavation is in progress, Mary Leakey hops into her white Peugeot station wagon, four dalmations hop in with her, and she drives off to check up on the dig’s progress. “Our chaps are quite experienced now and I really don’t have to spend any time supervising them,” she said, “They know what they’re looking for.”

The dogs are only the most conspicuous part of a Leakey menagerie that has, over the years, included a wide assortment of mostly African animals. A dozen mice and scores of colorful African birds visit the camp all day long to collect morsels dropped from the table and to feed on the oranges, bread crusts and water put out for them. Small genet cats come to the camp for bananas. Mary Leakey once had a baby wildebeest (Olduvai is in the area where the Serengeti wildebeest go in the wet season) that followed her around all day long. After it was fully grown, it tried to climb into the front seat of a Land-Rover to ride with her. The best pets, she says, are hyraxes, a common small African mammal that looks like a big guinea pig but whose closest living relative is the elephant.

Of all the animals at Olduvai, those that occupy most of Mary Leakey’s attention are the ones long since dead, the ones whose fossilized bones have been exhumed from the gorge. And, of these, the most puzzling animal is man. One of the mysteries posed by the hominids of Olduvai Gorge is “What happened to Homo habilis, the maker of the Oldowan tools?”

Homo habilis lived in Bed I times and into early Bed II, roughly 1.5 million years ago. “All along,” Mary Leakey said, “he gets more and more human and then he disappears. Then we get (Homo) erectus. What happened to habilis?”

Homo erectus is a much more advanced form of man. There would have had to be several intermediate evolutionary stages between H. habilis and H. erectus. At Olduvai, they aren’t there. If H. erectus evolved out of H. habilis stock, he did it elsewhere. One fascinating possibility is that erectus evolved out of habilis-like ancestors in some other place and then, like a conqueror, invaded the region around Olduvai, wiping out the remnant habilis people. That is pure conjecture of the sort Mary Leakey does not care for. Once she has written Volume IV of the monumental series of monographs on Olduvai, “I want to go back to Bed II. That’s where erectus came in. I’d like to know what really happened.”

Diagrams and sketches are from Volume 3 of the Olduvai Gorge series, by M. D. Leakey, published by the Cambridge University Press.

Received in New York on November 21, 1973

©1973 Boyce Rensberger

Boyce Rensberger is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner with support from the L.S.B. Leakey Foundation. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Rensberger, the Alicia Patterson Foundation and the L.S.B. Leakey Foundation.