Johannesburg, South Africa

In 1952 Helen Suzman seemed a poor bet to become South Africa’s most vilified and yet most internationally admired politician. She was young and pretty, rich and social, and the golf-playing wife of a Johannesburg doctor.

She ran for Parliament mostly because her husband thought it was a good idea, she did not expect to win, and — if the low keyed tone of her first campaign literature was any clue – perhaps she didn’t even care.

She did win, however, and she has won ever since. Today Mrs. Suzman is the only national office-holder unalterably opposed to her country’s notorious “apartheid” form of government. Outnumbered in Parliament by 165 to 1, she is the lone but eloquent advocate of civil rights and equal opportunity for blacks — and a more unpopular cause in South Africa is difficult to imagine.

“She has now got the name for being the official mouthpiece of permissiveness and all subversive activities in South Africa,” an enraged cabinet minister once fumed after Mrs. Suzman had questioned him pointedly about the indignities that South African law inflicts upon blacks.

Parliamentary rules forced the cabinet official to withdraw the remark, which he did, but he tried again with, “…the mouthpiece of everything evil, of everything un-South African, and of all people who want to subvert authority and decency….”

He was ordered to withdraw that remark, also, whereupon he sputtered to a stop and lapsed into angry silence.

In addition to name-calling in Parliament (usually something along the line of “tool of Communist agitators”), Mrs. Suzman also has to contend with abusive phone calls, heckling and hate mail.

She is not particularly bothered by it, she said in a recent interview at her home in the plush Johannesburg suburb of Hyde Park.

“I am provocative, and I admit this. It isn’t as if I’m only on the receiving end, a poor, frail little creature. I can be thoroughly nasty when I get going, and I don’t pull my punches.”

Nevertheless, the hostility aroused by Mrs. Suzman’s “integrationist” views does concern her supporters.

“I worry about her,” a male friend confided, “I worry about letter-bombs. I said, ‘Helen, have you thought about letter-bombs?’ And she said, ‘Of course I have, I’m no fool.’ And I said, ‘Well, what are you going to do about it?’ And she said, ‘Nothing.’”

The friend, a director of First National City Bank’s Johannesburg operation, concluded sadly, “She’s all alone up there, you know. Doesn’t even have anyone to go to lunch with.”

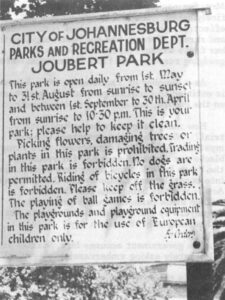

Few politicians in South Africa, it seems, care to socialize with someone who:

Dismisses as ludicrous the government’s plan to herd millions of black Africans into scattered “homelands” destined to become independent black islands within a white South Africa;

Demands repeal of the Terrorism Act and several other laws that permit arrest without charge, imprisonment without trial, and indefinite solitary confinement;

Proposes that the country’s windfall from the rising price of gold be used to improve health care, housing, transportation and education for blacks;

Urges higher wages and collective bargaining rights for black workers, along with an end to the “job reservation” system that legally prohibits even qualified blacks from working at “white” jobs, and

Believes that citizens’ morals can withstand the films (“Mash”, “Midnight Cowboy”), publications (“Playboy” and, inexplicably, the University of Natal’s student engineering journal) and advertisements (on packages of pantyhose) that have been banned by “old Mother Grundies” on the censorship board.

The “radical” views that 56-year-old Mrs. Suzman espouses with precision, scholarship and a crisp British accent, frequently annoy her colleagues in Parliament. But what really angers them is the fact that she has focused worldwide attention on South Africa.

Mrs. Suzman has , by invitation, conferred with heads of state in Europe, visited leaders of independent black nations in Africa, and addressed Congressmen in the U.S.

Most recently, Oxford University honored her as the South African politician “best known and most respected” overseas. A French magazine once ranked her (along with Golda Meir, Indira Gandhi and Shirley Chisolm) as one of 50 “most important women in the world today”, and a British publication called her “one of a handful of women who have made their names in international politics since World War II”. Countless other tributes, sometimes effusive to the point of embarrassment (“…lone flickering flame of liberty amidst the darkness that envelopes South Africa….”), have been widely quoted in the African and European press.

Most recently, Oxford University honored her as the South African politician “best known and most respected” overseas. A French magazine once ranked her (along with Golda Meir, Indira Gandhi and Shirley Chisolm) as one of 50 “most important women in the world today”, and a British publication called her “one of a handful of women who have made their names in international politics since World War II”. Countless other tributes, sometimes effusive to the point of embarrassment (“…lone flickering flame of liberty amidst the darkness that envelopes South Africa….”), have been widely quoted in the African and European press.

Still, the plain fact is that Helen Suzman’s 21-year battle against apartheid has been a failure.

If anything, the grip of apartheid has tightened in recent years and, to the distress of white liberals, new laws curbing freedoms of speech and assembly have made it increasingly difficult to mount any kind of opposition.

Mrs. Suzman readily admits that she has not accomplished very much. Asked to say exactly what, she once told the Rand Daily Mail, “It was probably my incessant nagging that resulted in policemen having to wear identity numbers.” As she explained, “It is useful to know who is hitting you on the head with a rubber truncheon.”

Beyond that, Mrs. Suzman concedes, she can do little more than get an occasional passport returned, or a banning order lifted, or the conditions of a political prisoner ameliorated.

But if Mrs. Suzman’s scorecard is depressingly lopsided, that fact does not seem to diminish her supporters’ ardor:

“Listen, she’s our champion,” a Johannesburg geologist said reverently, “If it weren’t for her, the rest of the world would think everything was just fine in South Africa.”

What keeps her going, through defeat after predictable defeat, is something that mystifies admirers and detractors alike.

Once, after Mrs. Suzman had delivered a particularly nettling speech in Parliament, Prime Minister John Vorster exploded, “Where are you heading? What are you and your Communist friends trying to do with South Africa?” To which Mrs. Suzman replied coolly, “We are trying to stop you.”

It is a quixotic goal, for both Mr. Vorster’s Nationalist Party, in power since 1948, and the United Party, the official opposition, share virtually identical views on race.

A Johannesburg political columnist pointed out that Mrs. Suzman, the only Progressive Party representative in Parliament, year after year must take on single-handedly both a “tough and ruthless” government and a “bitter and resentful” opposition party.

“That would be unpleasant enough for anyone,” he wrote, “But it must be doubly so for a woman, in an overwhelming male bastion of the kind which believes deep down that femininity belongs in the kitchen.”

To Mrs. Suzman, such considerations are beside the point.

“I represent all the enlightened people in this country,” she said firmly, “and that’s a fine thing to be able to do. It infuriates my opponents when I say this, but it is true.”

After more than two decades, Mrs. Suzman’s parliamentary skills are finely honed. She is a knowledgeable and effective speaker, a meticulous researcher and rarely, if ever, has she been caught with her facts wrong — a record that has won grudging respect even from bitter opponents.

After more than two decades, Mrs. Suzman’s parliamentary skills are finely honed. She is a knowledgeable and effective speaker, a meticulous researcher and rarely, if ever, has she been caught with her facts wrong — a record that has won grudging respect even from bitter opponents.

As a Member of Parliament, Mrs. Suzman is entitled to question government ministers on the record, and she does so incessantly:

How many people are being held without trial? What about the seventeen who died mysteriously while in detention? How many blacks are arrested each day for violating the “pass laws”? How many have been forced into resettlement camps by the Group Areas Act? What is being done for the three million black farm laborers bound to their employers by the Masters and Servants Act and earning only 28 cents a day?

The government accuses Mrs. Suzman of deliberately asking embarrassing questions.

“It is the answers, not the questions, that are embarrassing,” she retorts.

When what she considers outrageous legislation comes before Parliament, Mrs. Suzman becomes even more aggressive. A recent example was her vigorous opposition to the Gatherings and Demonstrations Act, which restricts and in some cases prohibits the right of peaceful assembly.

Mrs. Suzman attacked the bill at every reading. Then she opposed it, clause by clause, through the committee stage. Her amendments were rejected, and the bill passed overwhelmingly. She immediately called for its repeal.

Mrs. Suzman and her Progressive Party are, despite the “leftist” labels, quite moderate in their political philosophy.

Economically the “Progs”, as they are called, are unabashed capitalists who favor free enterprise, foreign investment in South Africa and rapid exploitation of the country’s vast mineral wealth. They oppose the boycotts and economic sanctions promoted by anti-apartheid groups in the U.S. and Britain, and even argue against the embargo on the sale of arms to South Africa.

“I can well understand Americans feeling strongly about anything that appears to bolster up an obnoxious system,” she said, “but I can say unequivocally that the boycott does not work. It’s never complete enough to have impact unless it’s backed by force, and I don’t think anybody in America seriously proposes that.”

Mrs. Suzman, a former lecturer in econontic history at the University of the Witwatersrand, believes that internal economic pressures are the only effective weapons against apartheid. She notes that as a result of recent strikes, wages of black miners are inching upwards and the government is being forced to modify its rigid labor policies.

“I have always held that the more rapid the economic development of this country, the more apartheid will come apart at the seams,” she said.

The “Progs” reject violence and guerrilla-style activity and are disturbed by talk in independent black Africa about armed intervention.

“This country is armed to the teeth, and none of these African states could begin to attack South Africa,” Mrs. Suzman said, “But of course all these stories are grist to the mill of the government because they build up a very useful war psychosis.”

Mrs. Suzman paused. “Tool of Communist agitators…,” her voice trailed off. “I mean, it’s really a joke, isn’t it? Because, quite clearly, we are a party of real moderates. It just shows how little they understand.”

Received in New York on January 24, 1974

©1974 Judy Rensberger

Judy Rensberger is married to Boyce Rensberger, an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner. This article may be published with credit to Mrs. Rensberger and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.