As readers of Robert Ardrey’ s African Genesis may recall, the first solid suggestion that man originated in Africa came in the 1920s when Raymond Dart painstakingly chiseled the fossilized skull of a pre-human child from a block of South African limestone.

Dart, then a young professor of anatomy at a Johannesburg medical school, spent four years scratching away the stone that enveloped the skull. He revealed, for the first time anywhere, a creature that looked like a possible ancestor to the human species, a link between hominids — the family of man — and pongids — the family of apes.

Today in South Africa Dart’s successors are still chipping away more rock to expose more pre-human fossils and they are studying the South African sites in new ways that are leading to some startling findings.

In eastern Africa — at Olduvai Gorge, East Rudolf and the Omo — fossils are found lying clean on the ground or, at worst, buried under a few feet of easily dug sediments. To get the South African fossils, you have to dynamite solid rock, shattering it into thousands of football-sized chunks that are broken into even smaller pieces in a hydraulic press. You find a fossil only if the rock happens to break through it so that it can be seen. Freeing the bones then requires hours of patient work with a hammer and chisel until all the encasing rock is removed.

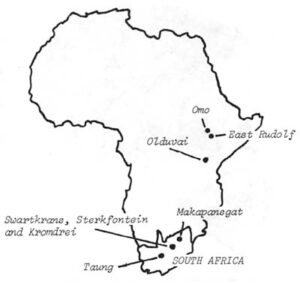

Still, the five South African sites have yielded almost three-quarters of all the hominid fossils found in Africa. About 90 percent of the South African fossils come from three relatively tiny but incredibly rich sites within a mile of each other in the farmland just an hour’s drive west of Johannesburg.

While the East African fossil hunters must hike for hours in the hot sun, ranging in a season over areas of dozens to hundreds of square miles, their South African colleagues may toil the entire year in a single pit or small cave.

The world’s richest source of fossil ape-men is an unimposing hillside called Swartkrans. Since the first hominid bones were discovered there in 1948, Swartkrans has yielded over one-third of all the hominid fossils found anywhere in Africa. Yet it is only a small pit into the hillside that takes less than a minute to climb down into as far as you can go.

A mile away, across the valley, is Sterkfontein, the world’s second most productive mine of early man fossils. Its excavations and cave mouths are protected by a chain-link fence enclosing an area no larger than 40 yards by 100 yards.

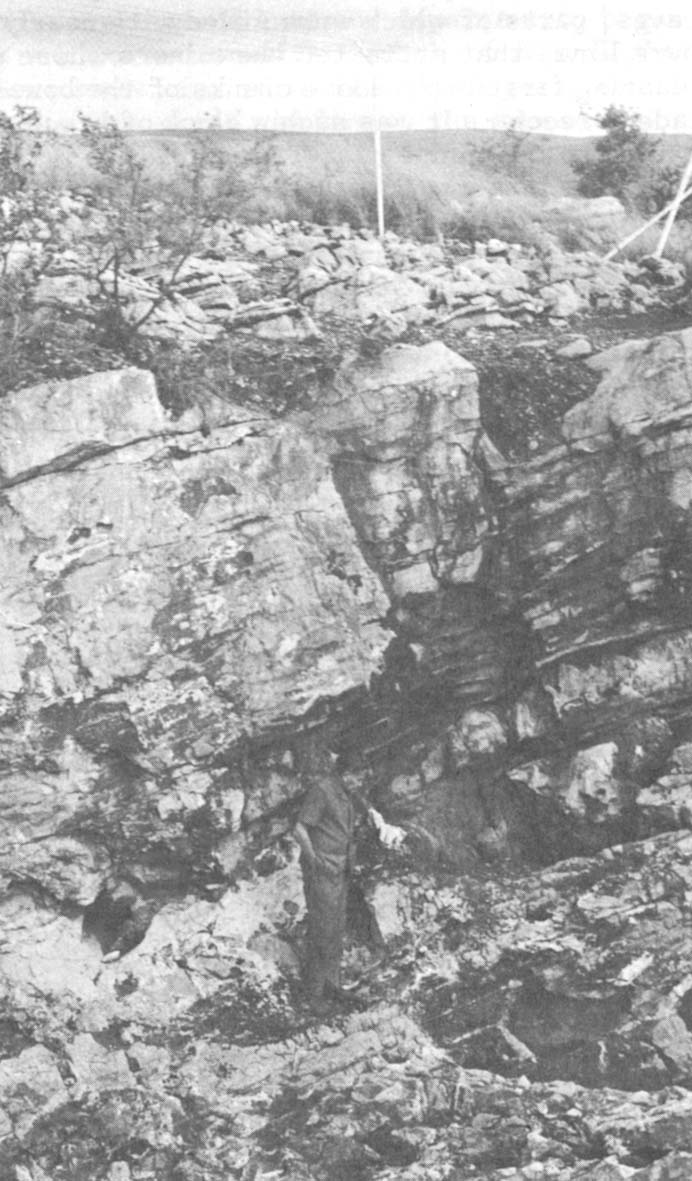

Less than a mile from Swartkrans is Sterkfontein, the second richest fossil-man site. Alun Hughes stands in one part of the excavation, his feet on solid rock in which thousands more bones are embedded.

“It may not look very big,” remarked Alun R. Hughes who supervises the field operations for Dr. Phillip Tobias of the University of the Witwatersrand, “but there’s decades worth of work here.”

Five decades have already gone into study of the South African fossils and yet, they remain something of an enigma. The very conditions that helped concentrate such a large number of bones into a few places and that then preserved them so completely in solid rock also have made it almost impossible to determine how old they are. The rock chemistry and physics on which dates are determined elsewhere does not seem to exist in the South African sites.

Lacking a date by which to plug them into the timetable worked out in East Africa and Asia, many experts in the field have tended to disregard the fossils for the moment — except to recall that South Africa provided the first specimens of the pivotal ape-man species Australopithecus ever to be found.

For its ultimate impact on the study of man’s evolution, probably no fossil rates higher than that first little child’s skull that Dart discovered in 1924. Prior to then the scientific world had little more to work with than Darwin’s opinion that man and ape evolved from a common ancestor and a few fossils that proved there once were men of a more primitive sort than we.

Skulls of Neanderthal Man were found as early as 1848 and 1856. In the 1890s Eugene Dubois found some bones in Java that appeared to belong to a still more primitive hominid. Yet, all the bones were clearly manlike. Still missing was the creature that linked man with the apes.

That was what Dart believed he had found. The Taung baby, as he nicknamed it for the site of its discovery, (actually it was about five years old), looked too ape-like to be human but too man-like to be an ape. Dart recognized this extraordinary combination of features and published his interpretations but few of his colleagues accepted the Taung baby as a possible human ancestor. If Dart’s report evoked any comment, it was astonishment that an ape would have ventured so far out of the forests of central Africa to inhabit the dry, open grasslands that South Africa has long been. And, anyway, most people had forgotten Darwin’s second suggestion: that man evolved in Africa. Asia or the Middle East were the accepted human homelands.

In the next two decades, however, further finds of similar creatures gradually won over the leaders of anthropology. Recently, however, new evidence has led some authorities to suggest that, after all, Australopithecus may not have been ancestral to man. The South African ape-man and the dozens like him found in East Africa may have been only cousins to Homo, both having descended from a common ancestor. However the new doubts are resolved, Dart’s find retains its historical importance for it inaugurated the search for fossil man in Africa. By the 1940s and 1950s Africa was coming to be regarded as the birthplace of man. Yet, in the popular press, little attention went to Africa. Between the two World Wars Peking Man generated the headlines and school children continued to be told that man began in Asia.

In 1959 the discovery by Mary and Louis Leakey of what they called Zinjanthropas (now considered a form of Australopithecus), finally turned public attention to Africa but 1800 miles north of where the first crucial fossil was found. And, although East Africa has been the scene of the most publicized finds to date, the small but productive South African sites have continued to yield a seemingly endless flow of hominid fossils.

The extraordinary richness of the sites is a consequence of the way they were formed. Unlike the East African situation where bones were buried where they lay under sediments of lakes or rivers, South Africa preserved its hominid bones because they somehow accumulated in caves.

At various times in the past weakly acidic underground water dissolved away volumes of dolomite rock, honeycombing the subterranean world with caves that had no opening to the surface. One by one, as the overlying soil in hilly areas eroded away, the caverns were opened and most anything on the ground above could fall, walk or be dragged into the cave. For perhaps hundreds of thousands of years pieces of the outside world accumulated in the caves, slowly filling them. Water, dissolved minerals and various geologic processes gradually solidified the heaps of bone and rubble into conglomerate rock, or breccia.

It is this breccia through which workers must blast and crush their way to recover the ancient bones. It is also these same caves, parts of which were filled with nearly pure lime, that attracted the miners whose blasting first broke loose chunks of the bone-laden breccia. It was such a block of breccia from the lime mine near Taung in which Dart found his historic fossil. Today the Taung site is gone, totally mined away. Of the remaining four South African sites, only three are actively studied today: Sterkfontein and Swartkrans, near each other, and Makapansgat, some 200 miles north of Johannesburg. The fourth, Kromdrei, near Sterkfontein and Swartkrans, is scientifically dormant.

One of the most puzzling of the questions surrounding the South African sites is the mystery of how the bones got into the caves in the first place. Some say the apemen lived and died in the caves and that the animal bones found there are the remains of their food. Others say that hyenas dragged the bones into the caves, feasting on hominids as readily as any other beast.

Perhaps the theory that has the most intriguing evidence to support it is that leopards were responsible. This is the view of C. K. Brain, a scientist from the Transvaal Museum in Pretoria who has been in charge of the Swartkrans dig for many years. His theory applies only to Swartkrans.

Brain noticed that of the large number of hominids and baboons represented in the fossils, an unexpectedly large proportion were of very young or very old individuals — fitting the typical age distribution of animals killed by many predators. There were comparatively few creatures who died in their prime. Brain also found a number of skulls bearing two small puncture wounds with no signs of healing, suggesting that they were inflicted at the time of death. He compared the distance between the two wounds with the gap between the long canine teeth of various carnivores and found the closest match with those of the leopard. In fact, in many cases the wounds were just where they would be expected if a leopard had clamped down on the victim’s head and dragged the corpse between its legs.

Leopards do not commonly take their kills into caves. More typically they drag them up into trees and wedge them in a fork to protect them from scavengers. In the dry Transvaal the biggest trees grow in crevices such as those at the mouths of caves, where water accumulates.

What may have happened, Brain speculates, is that leopards preyed on early man, catching mostly the weak ones — the very young and the very old — and dragged them into trees such as those at the mouths of caves. As the hapless hominid was eaten or perhaps left to rot, its disjointed bones dropped into the cave below.

A similar age distribution of prey animals has not been found at the other sites, nor have skulls with tooth marks. In some of the others, however, stone and bone tools have been found suggesting that the hominids may have inhabited the caves. Some authorities doubt this, noting that some of the hominid bones were found in layers reaching almost to the cave’s ceiling and frequently deeper into the dark cavern than a creature with no control of fire would seem likely to have ventured.

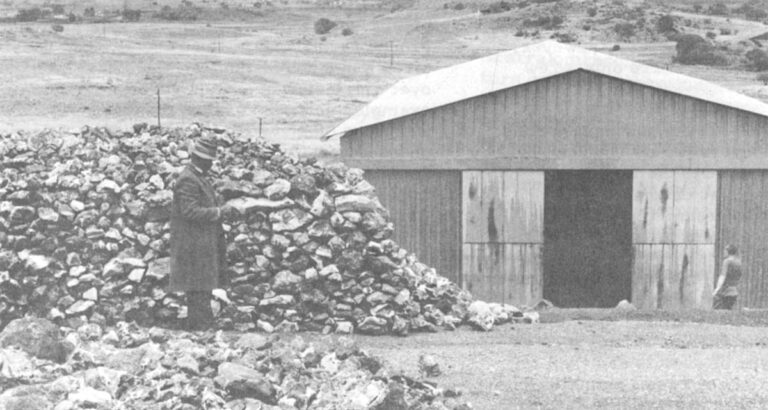

From the base of the trees that, even now, grow near the mouth of the Swartkrans cave, one can see the big metal shed that houses the tools, fossils and breccia-breaking presses of the dig at Sterkfontein, the scientific continuation of a commercial effort that began nearly 70 years ago.

In the 1900s, lime miners at Sterkfontein began blasting out chunks of the filled-in cave. Frequently they knocked loose chunks of breccia containing fossils. On Sundays, when visitors came, the miners sold fossils. In the 1930s they also sold a guidebook that, recalling Dart’s find, invited: “Come to Sterkfontein and find the missing link.”

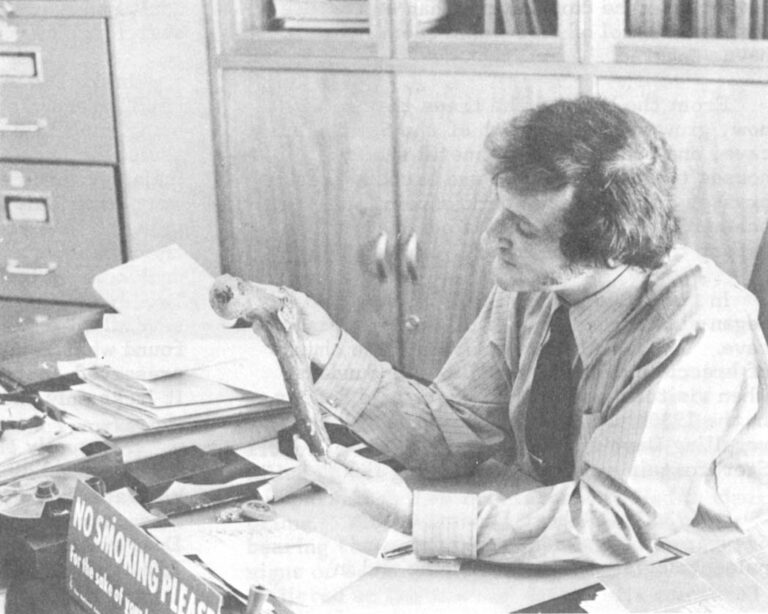

In 1936 Dr. Robert Broom, then a 69-year-old physician, zoologist, and paleontologist, visited the mine and in barely a week found pieces of an Australopithecus skull. Twelve years after Dart’s scoffed-at Taung baby, there was confirmation. Broom’s skull was that of an adult and it prompted a more intensive search for more hominid remains.

Unlike Dart who rarely went into the field, preferring instead to have others bring him their finds, Broom and a young assistant, John Robinson, carried out a major program of excavations. Visitors were invariably amused at Broom’s attire. In even the hottest weather, he worked amid the rocks and rubble in a carefully tailored dark suit with vest and high starched collar. Broom and Robinson’s years of work yielded several dozen new specimens. In 1947 they found what remains one of the most perfectly preserved Australopithecus skulls ever found. It lacks only the lower jaw and teeth.

Eventually the work ceased until 1966 when Tobias, head of the University of the Witwatersrand’s anatomy department, began a new excavation with the help of Alun Hughes. Ever since, for 48 to 50 weeks a year, ten African workers who live on the site with their families, have been patiently smashing and sifting their way through the blocks of discard rubble for overlooked fossils and going into the caverns with miners’ lamps to blast out more breccia.

At Makapansgat, another limestone cave, excavations that were discontinued in 1961 after 14 years, were resumed earlier this year. Because of its remoteness, however, it is practical to excavate there only a few months each year.

A major aspect of all the new excavations has been to try to find minerals that can be dated by one of the various methods now available. Despite great efforts and the assistance of experts around the world, no datable minerals have been found.

Until just this year, the only method that could even suggest dates was one called faunal correlation. Very simply what one does is to look at the various animal species found in a given layer of fossils and then try to find a similar array of fossil animals from deposits elsewhere that are reliably dated.

As man was evolving in Africa, so were many of the other mammals he lived with. A million years ago the antelopes, elephants, zebras and wild pigs of today were in a more primitive form. Some of today’s species had not yet evolved. Some of the species alive then are extinct today. Two million years ago many forms were still more primitive. Experts on the various mammal groups have found in the East African fossil sites a number of clear evolutionary changes over the last few million years. If, for example, scientists know that there are warthogs of a certain type in a given layer of undated fossils, then it is likely that those fossils were deposited at about the same time as were similar fossils in a dated East A frican site.

frican site.

Because of possibly large ecological differences between the two regions that could produce contemporary but different sets of animals, the method is not very accurate in this case. Nonetheless, using the “calibrated pigs” of the Omo, Dr. Basil Cooke of Dalhousie University in Halifax, has estimated that, for example, Sterkfontein and Makapansgat date from about 2.5 to 3.0 million years ago. Princeton’s Dr. Vincent Maglio has studied the Makapansgat elephants and come up with the same dates by comparing them with extinct elephants found in the Omo and elsewhere.

Now, however, Tim Partridge, a consulting geologist in Johannesburg, has devised a new method of dating the South African sites by calculating when the land over the closed caverns eroded away to open the caves to the surface. Partridge’s method capitalizes on the fact that the caves are situated in ancient river valleys and were opened when a fast-erosion phenomenon called the nick point had receded up the river to reach the caves — somewhat in the way any waterfalls slowly etches its way upstream — to wash away the cave’ s roof.

Partridge’s calculations, although involving many estimates and unconfirmed techniques, come remarkably close to agreeing with the pigs and elephants. The new calculations, which will soon be published in the prestigious British journal Nature, offer the first tentative absolute dates for the South African fossils.

The report should attract much attention in the anthropological world and, if it is not seriously challenged, it could lead to new interpretations of how man evolved.

The biggest surprise is likely to be in the date for Taung, the grave of Dart’s five-year-old Australopithecus child. Once thought to be among the oldest of the Australopithecine fossils, Taung now may turn out to be the youngest. Tobias said that if the Taung cave opened when Partridge calculates it did, the little creature may have died no more than 750,000 years ago — well into the days when, elsewhere in Africa Australopithecines had long since evolved into human beings who were flourishing with Early Stone Age tools like handaxes and cleavers.

The Taung baby, Tobias said, may represent “the old ‘hairies’ surviving in a little relict population on the edge of the Kalahari” more than half a million years after they were thought to have become extinct.

Received in New York on November 2, 1973

©1973 Boyce Rensberger

Boyce Rensberger is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner with support from the L.S.B. Leakey Foundation. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Rensberger, the Alicia Patterson Foundation and the L.S.B. Leakey Foundation.