Thirteen years ago Robert Ardrey published his African Genesis, popularizing Raymond Dart’s old theory that man evolved from a “killer ape” whose murderous instincts remain deeply ingrained in us, despite a veneer of civility.

For many of the thousands who read the book and of the millions who heard about it, the theory remains a chilling but plausible explanation for the brutality of modern man. The theme of man’s innate depravity has been further dramatized in such works as William Golding’s Lord of the Flies. The idea even offers some escape from guilt: We are born this way and we can’t help it.

The killer ape hypothesis, however, is an idea whose time has gone. In fact, most of the leading scientists who study the evolution of man say the theory never was accepted. Despite Ardrey’s skillful use of his dramatist’s talents to tell a compelling tale, few scientists have found enough hard evidence to support the notion.

The blood drenched story that Ardrey presents as inescapable scientific truth has its roots not in evidence and not in Africa, but in Ardrey’s own emotions about Africa. Ardrey’s visit to Africa was initially to cover Kenya’s Mau Mau uprising for The Reporter Magazine. His first exposure to the fossils, upon the ambiguous features of which much of the argument rests, was mixed with hearing tales from white settlers terrified by rumors of Mau Mau murders. The black freedom fighters, it was widely held, had taken secret oaths in the dark of night and amid grisly rites of sacrifice. They had shed the European’s cloak of civilization and reverted to animals crazed by the taste of blood. It was much the same exaggerated story from which Robert Ruark spun his allegedly based-on-fact novels.

“I sampled in the terror-brightened streets of Nairobi the primal dreads of a primal continent,” Ardrey wrote in African Genesis. “I learned to fear for my life in a thousand ways, and in a thousand moments to yearn for the mortal security of civilization…. Africa scared me. If this continent had indeed been the cradle of humankind, and I had been the first man then I should have been born in fear.”

The book goes on to make the case that Homo ardreyensis could have survived only by using the deadliest weapons he could find or make to defend himself and to slay his murderous brothers lurking in the dark. The ape-men who could make the best weapons or use them most skillfully survived; those who could not perished, the direct victims of the weapons. The instinct to kill survives in its purest form, Ardrey argued, in adolescent street gangs where vibrant youth, still unfettered by the artificial restraints of culture, remains as dedicated to the switch-blade knife as its ancestors were to the bone club or the flint-edged dagger. Ardrey contended that young thugs such as those of West Side Story (“No other work of art…offers such a vivid portrayal of the natural man.”), are mentally healthier than civilized adults. This, he said, was because they lived in harmony with their animal instincts.

“Man is a predator whose natural instinct is to kill with a weapon,” Ardrey declared. On the larger scale, this instinct reveals itself in mankind’s giant organizations and machines for making war. In fact, Ardrey argued, the histories of man and lethal weapon have been so intertwined for so long that man has become utterly dependent on weapons and cannot live without them.

Most of the philosophical and sociological premises and consequences of Ardrey’s beliefs were rather ably rebuked in a little 1968 volume titled Man and Aggression, edited by Ashley Montagu. It is a collection of essays, most of which appeared earlier in general periodicals. Yet, strangely, the book has no contribution by an expert in the fossils that first sparked Ardrey’s imagination. Much of Ardrey’s case rests on the finding of some fossil skulls and jaws of Australopithecus (an ape-man long considered a human ancestor) that were broken in what appeared to have been assaults by fellow Australopithecines. Murder, in other words.

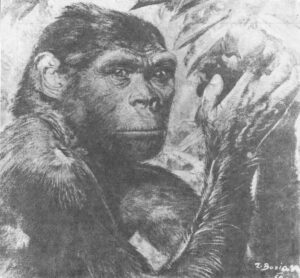

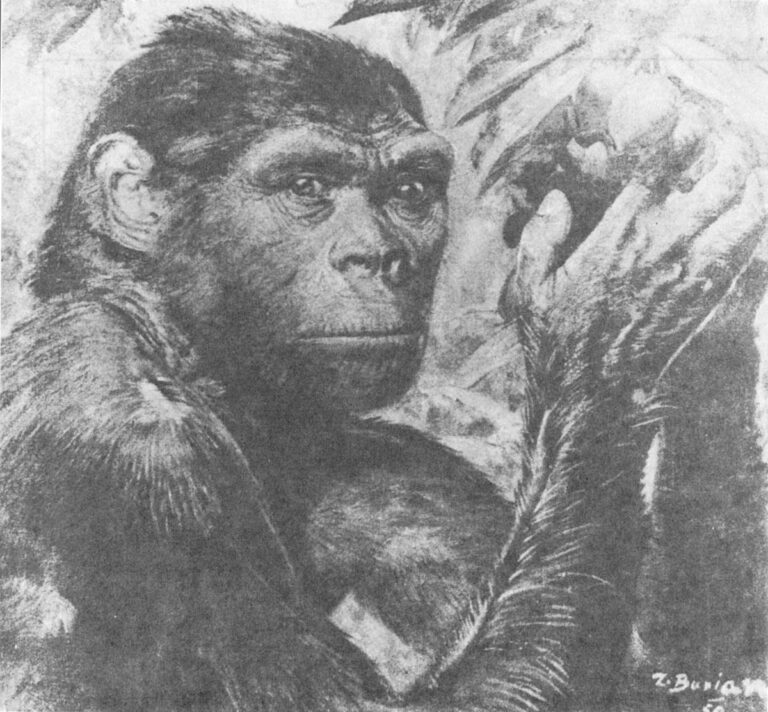

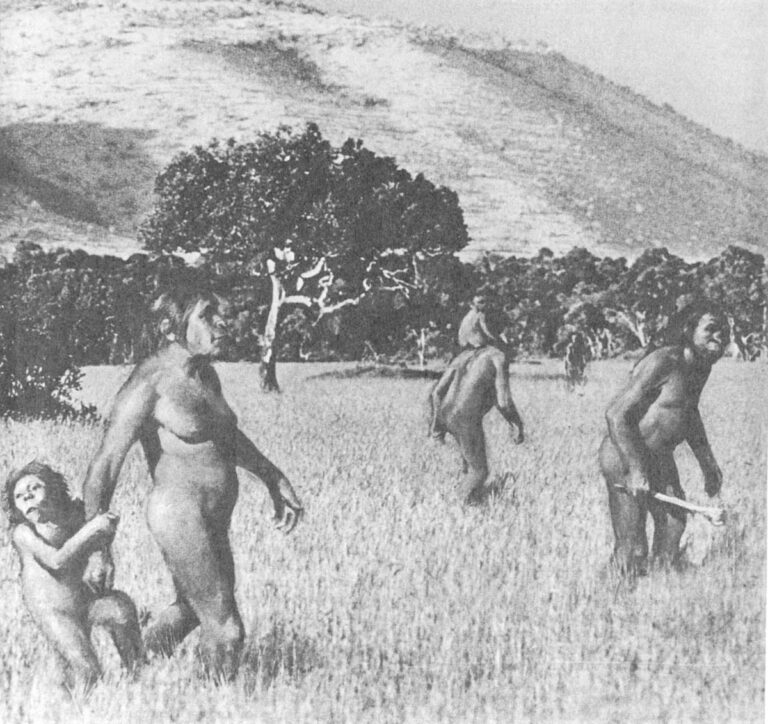

In 1953, two years before Ardrey began his study in the subject, Raymond Dart wrote a paper entitled “The Predatory Transition from Ape to Man.” Dart argued that a certain evolving line of apes diverged from the typically herbivorous habits of its predecessors, and acquired a taste for meat which it hunted as a predator. As Dart saw it, the apes evolved the upright posture, which made possible the dextrous hand, which made possible the fashioning and use of weapons, which made possible the more efficient killing of prey. Man emerged from apedom because he was a hunter, Dart said. The demands of hunting made opportunities for increasingly intelligent creatures to prosper, becoming still better hunters.

That much accords reasonably well with today’s views but Dart went further. He argued that it was but a short step from killing animals for food to murdering one’s own kind. As the near-men came to rely more and more on their improving weapons, Dart seemed to imply, they evolved to become more behaviorally at home with them and came rather to like the killing business. The ones who had the best weapons (sharpest minds) and the strongest stomachs prospered and had no qualms about murdering their less violent brothers who, of course, were holding back progress.

In his paper Dart wrote, rather verbosely, “The blood-bespattered, slaughter-gutted archives of human history from the earliest Egyptian and Sumerian records to the most recent atrocities of the Second World War accord with early universal cannibalism, with animal and human sacrificial practices or their substitutes in formalized religions and with world-wide scalping, head-hunting, body-mutilating and necrophiliac practices of mankind in proclaiming this common bloodlust differentiator — this predacious habit, this mark of Cain 1 that separates man dietetically from his anthropoidal relatives and allies him rather with the deadliest of Carnivora.”

That paper could hardly have had greater impact than to have been read or pondered in the heart of “primal” Africa during the time of Mau Mau — in the very place, if not the time, where man was born.

Building on Dart’s views, Ardrey contended that near-man’s weapons (necessary in the absence of sharp teeth or claws) became the all-consuming focus of his existence. In Ardrey’s view, the weapon became and yet remains man’s “most significant cultural endowment.” In part this was based on Ardrey’s view that most of the cultural artifacts found with the remains of early men were not merely tools, as most archeologists call them, but weapons. Ardrey considered “tools” a euphemism. Statistically, the contention never held up. The choppers, scrapers, burins, awls, hammerstones, handaxes and flakes of various sorts would have made poor weapons with which to kill anything. Most authorities believe they served a variety of household utility functions. Of course, no one doubts that an early hominid could have taken a chopper, originally fashioned for another purpose, and bashed his brother on the head. It could have been as dangerous as a baseball bat or a tire iron.

Undoubtedly, early man had weapons with which to kill his prey. He probably used wooden clubs (which do not fossilize well) or threw rocks (which keep but look like any other rock). One probable method of killing, deduced from the circumstances in which butchered and fossilized animals have been found, was to drive the prey into muddy ground which would hold the animal almost immobile until it could be clubbed or stoned to death. Such a killing method relied more on cunning and planning than on the invention of a superior material weapon. Long before the first evidence of spears or arrows, man was undoubtedly an accomplished hunter. He relied not on fancy weapons, but on his brain, to make snares, or drive animals over cliffs or into pits or to surprise them while they slept. It also seems likely that early man would have tried to steal the prey of lions, hyenas and other predators. Various animal predators steal the kills of one another quite often and, no doubt, our ancestors saw how easy it was. Modern people on foot can easily scare lions off kills with a few shouts and waves of the arms.

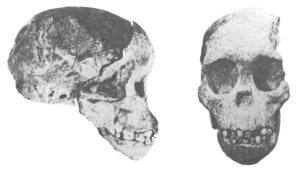

The fossil evidence that Dart offered and which Ardrey felt so compelling included a number of baboon skulls found with the bones of Australopithecus and bearing the damage of a blunt instrument. The clear suggestion was that the ape-men bashed the skulls with a weapon and ate the creatures. Ardrey’s book ominously declared, “The use of weapons had preceded man.”

Still, hunting is not murder. The fossil clincher for Ardrey was the jawbone of a 12-year-old Australopithecus. The jaw had been broken before its owner died. A dent on the chin had knocked out some front teeth and the bone was broken on either side. Ardrey said that because the break had not knitted, the blow on the chin was fatal. Although the creature probably died shortly before or after the blow on the chin, Ardrey does not discuss the possibility — even the probability — that death came from damage to some more vital organ than the chin. There is no evidence of how that damage might have been inflicted.

“What if a weapon had done this deed?” Ardrey wrote breathlessly. “What if I held in my hands the evidence of antique murder committed with a deadly weapon a quarter of a million years before the time of man?”

Ardrey also cited seven other ape-man skulls that had been fractured but even he cautioned, “Not all the specimens demonstrate conclusively death by purposeful violence.” He singles out only three of the seven — one that had been bashed in a way resembling the damaged baboon skulls; one in which a two-inch rock had been rammed through the skull, coming to rest in the brain case; and one which bore two small punctures that could have been inflicted by assault with a sharp stick. Ardrey does not suggest the nature of the weapon and discounts the possibility that the holes are tooth marks from a predator.

One did not need more evidence or more expertise to determine what had happened, Ardrey said. Of the broken jaw, he insisted, “One needed nothing but the lay common sense of a juryman to return a verdict that at some terrible moment in most ancient times, murder had been done.”

That is the sum total of the direct evidence for murder and an affinity for lethal weapons being an instinctive, species-wide trait among man’s ancestors. That some of the skull fractures might have resulted from falls or other accidents (ceilings sometimes collapsed in the South African caves in which the fossils were found) was not considered a likely possibility. The balance of Ardrey’s 357-page book is taken up with indirect suggestive evidence and descriptions of territorial and aggressive behavior among animals far removed from man’s line of evolution. Curiously, Ardrey discounts behavioral studies of man’s two closest living relatives, the gorilla and the chimpanzee both of which are remarkably amicable and non-combative animals.

African Genesis was published just as the wealth of discoveries at Olduvai Gorge began to come in and long before anthropologists began their searches in the Omo and in the fabulously rich East Rudolf area. It is quite fair to say that the vast bulk of today’s knowledge about man’s evolution was discovered and studied since Ardrey’s book came out. In fact African Genesis stimulated much of the financial support that made possible the later work. How has the killer ape theory held up? Very simply, it has not. The additional fossil evidence that might have been expected has not been among the hundreds of additional hominid fossils that have come forth.

Today the vast majority of experts familiar with the fossil evidence agree that while man’s ancestors appear to have been hunters, killing and consuming quantities of meat, there is no suggestion they were driven by a bloodlust any more than any other predator. There is certainly no hint that they killed each other any more than does any animal species known today. Modern studies of the behavior of wild animals has revealed that many species kill members of their own kind far more frequently than human beings murder each other. In fact, by comparison with most of the species studied, man is a much more peaceable and less aggressive creature — even when the carnage of modern wars is averaged in. The incredible development in weapons that has undeniably taken place is a comparatively recent phenomenon, occurring only in the last one-tenth of one percent of the time man has existed. The cause may reasonably be sought in the conditions of human society that obtained during this recent period of perhaps 3,000 years.

“The killer ape theory should have been abandoned by everybody long ago because there’s really no evidence any longer to substantiate the view,” said Richard Leakey whose expeditions at East Rudolf are regularly turning up spectacular new evidence of the evolution of man.

“The evidence for a predatory early hominid is perfectly valid,” Leakey said, “but a predator ape is not a killer in the sense that the ‘killer ape’ was introduced and is popularly conceived of. I think it is very likely that nobody would have heard of the killer ape concept if it hadn’t been for Robert Ardrey but in the same breath I will say it is certain that a majority of the people now interested in supporting early man research would never have heard of early man. I think Robert Ardrey has done a tremendous amount to bring in the interests of people around the world and if the price was the killer ape hypothesis then I think it’s cheap at the price.”

Mary Leakey and Clark Howell, two others eminently familiar with the latest fossil evidence, say much the same thing.

Phillip Tobias, a student of Dart and his successor as professor of anatomy at Johannesburg’s University of the Witwatersrand, said, “I don’t go along with this killer ape hypothesis myself. I don’t think there’s good evidence to regard these creatures as having been unduly murderous in instinct.”

Tobias, who is an authority on both the South African fossils and those of Olduvai Gorge, said the teeth of early men and the food remains in his camps suggest he was omnivorous, eating not only meat but fair amounts of vegetable matter as well. “There’s quite a lot of evidence,” he said, “of muddled thinking in the claims which attribute these murderous, bloodthirsty, slavering, meathungry instincts to the early hominids.”

In any event, Tobias feels it is fallacious to suppose that the behavior patterns of man today could invariably be guided by the same forces that moved Australopithecines. “I believe,” he said, “there is a certain amount of mixing or even confusing, dare I say it, of levels of organization to jump straight from Australopithecus to West Side Story.”

Tobias feels there are indications that the evolutionary steps that took place between Australopithecus and modern man included quantum jumps in mental ability that, among other things, conferred an ethical sense quite unlike anything in lower animals.

There is another line of evidence against the Dart-Ardrey contention. Even assuming that Australopithecines were as murderous as the pair said, there is growing — although not yet conclusive — evidence that Australopithecus was not an ancestor of modern man. When Ardrey wrote, virtually everyone in the field considered Dart’s Australopithecus a likely human ancestor. Since then new fossils have come to light, especially from Richard Leakey’s East Rudolf area, suggesting that man had already arrived on the scene before most of the Australopithecine individuals so far found ever lived. Some authorities now consider that the first man shared a common ancestor with Australopithecus and that Dart’s ape-man was an evolutionary dead end. Richard Leakey claims to have found a member of the genus Homo (meaning he considers it true man) who lived nearly three million years ago. The remains of the most Homo-like creatures older than that are scant — a jaw fragment here, a tooth there. They are not enough to say for sure whether they were Australopithecines or something else — and certainly not enough to say whether their lives were devoted to the perfection of lethal weapons.

For his part, Dart stands by his views. Although now 80 years old and retired from his university post, Dart remains active, dividing his time between the Institute for the Advancement of Human Potential in Philadelphia and the Bernard Price Institute for Paleontological Research in Johannesburg, Dart continues to devote much of his energy to problems of aggression and violence in man and to his not-widely-shared theory that before stone tools, early man had a culture based on tools of animal bones, teeth and horns — the very weapons with which Dart believes man’s ancestors first learned to kill. Dart said that recent psychiatric writings on aggressive impulses in modern man support the idea that they are inherited instincts. “Whether being in the 80s adds to or detracts weight from one’s opinions is not for me to judge,” Dart said, “but mine have not altered. So I am incorrigible.”

Received in New York on December 4, 1973

©1973 Boyce Rensberger

Boyce Rensberger is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner with support from the L.S.B. Leakey Foundation. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Rensberger, the Alicia Patterson Foundation and the L.S.B. Leakey Foundation.