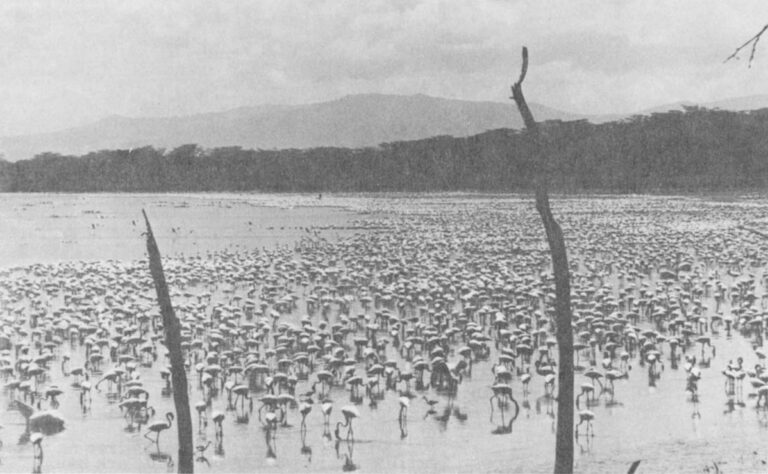

From the road that runs over nearby hills one can look out over Kenya’s Lake Nakuru and see a ribbon of pink fringing virtually the entire shoreline. The “pink” is all you can see from that distance of the hundreds of thousands — sometimes over a million — flamingoes that live in this remarkable lake habitat.

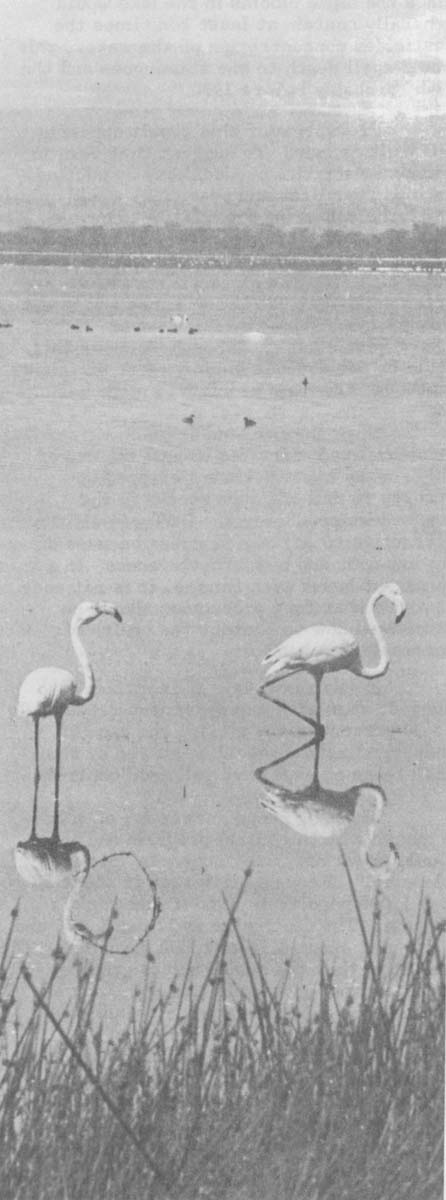

One can walk for miles along the shore, assailed by the constant gabble of thousands of closely herding flamingoes always within earshot. All day long they stilt through the shallows, swishing their beaks back and forth under the water to filter out the algae that is their chief food.

Living in and around the same lake are tens of thousands of white pelicans, thousands of cormorants, herons and storks and varying numbers of some 400 other species of birds.

Roger Tory Peterson, the ornithologist, once called Lake Nakuru, “the world’s most fabulous bird spectacle.”

Not one mile from the northern shore, however, is the town of Nakuru whose 50,000 inhabitants pour some 1.1 million gallons of partially treated sewage into the shallow, 18-square-mile lake every day. Between the town and the lake is a vast city dump where everything from junked automobiles to garbage rots, slowly feeding a modern array of synthetic chemicals into the soil where rainwater flushes it into the lake. To the east, south and west of the lake is agricultural land where DDT, dieldrin and a host of other pesticides are widely used. These too find their way into the lake and, according to scientists, may soon reach levels that could wipe out much of the bird life.

At the current rates of input, the concentration of pesticides in the lake is likely to increase tenfold in 15 years. The Environmental Pollution Research Unit of the Kenya National Parks estimates, however, that before then the fish and flamingoes would be dead. Already a few pelicans are dying from what is believed to be the combined effects of several toxic chemicals each of which exists in sub-lethal levels.

This Western-style environmental threat is not unique in Kenya. Despite Africa’s “underdeveloped” economic situation, parts of the continent are now plagued by many of the same environmental ills once associated only with the highly industrialized countries.

An oil refinery spews tons of sulfur dioxide into Mombasa’s air and oil spills from tankers in the harbor threaten coral reefs along the Indian Ocean coast. Crude oil imports increased tenfold in a recent six-year period producing an equivalent increase in air pollution. Automobiles and smoke belching busses choke Nairobi’s streets. Detergent foam froths up on and sewage smells emanate from several of Kenya’s rivers. Many of the small streams (the country has no large rivers) carry the raw wastes of scattered slaughterhouses, tanneries, paper mills, coffee plants, and sugar factories. Pesticides, including some long-lived ones banned in the U.S. and fertilizers, which can be toxic, are being sprayed over more and more farmland in a desperate attempt to boost food productivity to meet one of the world’s fastest population explosions. Kenyan officials estimate that some 95 million pounds of fertilizer and nearly five million pounds of pesticides are used in the country each year.

Lake Nakuru is nowhere near Lake Erie and Kenya’s cities are environmental paradises compared with New York or Gary. But, American style pollution is creeping up on Kenya and many other growing African countries almost faster, it seems, than the benefits of industrialization. Lake Nakuru is a prime example.

One of the world’s most beautiful natural habitats is taking the brunt of the water pollution, pesticide pollution and solid waste pollution of a town growing at an annual rate of 6.8 percent and an agricultural region that must feed the increasing millions of Kenyans who live in arid parts of the country.

Yet Lake Nakuru is also the scene for one of Kenya’s first and most ambitious environmental monitoring programs. It is an effort that could become the prototype for an ecological early warning system to be used throughout Africa.

The same natural factors that make Lake Nakuru so vulnerable to pollution are also the ones that make it such a remarkable habitat for flamingoes and other birds in the first place. Although the lake is fed by three small seasonal streams and a freshwater spring, it has no outlet. Only evaporation removes water. Thus, over the lake’s history, the dissolved minerals brought in by the rivers become increasingly concentrated because they do not evaporate. This makes Nakuru, like many Rift Valley lakes, an alkaline or soda lake. It is not so alkaline, however, that fish cannot live. One species thrives. Nothing, however, grows in the lake like a species of blue-green algae called Spirulina. Because of Nakuru’s altitude — 5,800 feet — which exposes it to intense sunlight and an abundant supply of organic matter from bird droppings, the algae grow prodigiously, doubling their numbers every few hours on sunny days.

Spirulina is the flamingo’s favorite food and Nakuru’s flarningoes sift out of the water an estimated 150 tons of it every day, returning an equivalent amount of droppings. Some 28 hippos also help enrich the lake by grazing on land during the night and returning to the lake to laze away the days.

Because the lake is very shallow — only about six feet deep at the most — and has no steep banks, it makes vast areas available for the “grazing” flamingoes. So, although there are flamingoes in most Rift Valley lakes, nowhere do they reach the concentrations to be seen at Nakuru.

Nowhere, either, do the water pollutants reach such concentrations. The levels of DDT and DDE (a toxic breakdown product) range up to 0.27 parts per million in lake algae and up to ten times that level in fish that feed upon the algae. Lake Nakuru’s pelicans have concentrations of DDT/DDE averaging 0.53 ppm. Fish eagles, cormorants, storks and flamingoes carry lesser concentrations ranging down to 0.27 ppm.

“Present levels of pollutants in the Rift Valley area,” said Paul I. M. Chabeda, head of the Environmental Pollution Research Unit, “are generally still in the sub-lethal range. However, for some wildlife of the Lake Nakuru ecosystem, the situation may well become disastrous.

“At the present rates of input the concentration of organochlorine (chlorinated hydrocarbons like DDT) pesticides in Lake Nakuru is likely to increase tenfold by 1990. Since the algae blooms in the lake would generally contain at least ten times the pesticides concentration of the water, this would spell death to the flamingoes and the fish, probably before 1990.”

Prevention of this result appears difficult at best. To suggest that Kenyan farmers sacrifice productivity by cutting back on fertilizer and pesticides would only shift the suffering from birds to people. However, much could probably be achieved by agricultural extension programs to teach more efficient use of fertilizers which are often applied at the wrong times and in the wrong ways. More crucial however, is the use of pesticides. Although some of this could be cut down by similar more efficient methods, the main problem is more basic.

When the U.S. and other industrialized countries banned the use of DDT, many manufacturers stepped up efforts to sell off huge stocks in the “underdeveloped” world. DDT was already attractive to African farmers because of its low cost and high effectiveness. In a continent beset with famine, it is not easy to argue that food production should be sacrificed now to protect the health of generations yet unborn.

In the same way, it is difficult to suggest that with unemployment rates of 20 to 30 percent in the cities, the pace of industrialization should be slowed by the insistence on expensive pollution controls.

The long range answer is, of course, a massive birth control program and the Government officially supports “family planning.” Kenya’s birthrate is about 50 per 1,000 population, one of the world’s highest. The death rate is 17 per 1,000 and falling at about 0.5 per 1,000 each year. The result is that the population is growing almost three and a half times as fast as that of the U.S. (3.3 percent annually as against 1.0 percent). Officials optimistically hope that with a massive and successful birth control program, the growth rate can be cut to only twice that of the U.S. by 2000.

“In the face of Kenya’s population growth and increasing urbanization,” Chabeda said, “it seems inevitable that man will have to coexist with some degree of pollution in the environment, by compromise.”

Few people here argue that stiff pollution controls should be imposed now. Rather they, like Chabeda, suggest a compromise that involves monitoring the pollution (the Nakuru research is the prototype) until it reaches the danger level and then doing something about it.

Idealistic Americans often say to Kenyans, “This is still a beautifull country. You should start now to protect it. You should learn from our mistakes in the United States.”

Kenyans almost invariably reply something to the effect of, “Give us your standard of living and we’ll take your pollution too.”

Received in New York on January 28, 1974

©1974 Boyce Rensberger

Boyce Rensberger is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner with support from the L.S.B. Leakey Foundation. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Rensberger, the Alicia Patterson Foundation and the L.S.B. Leakey Foundation.