February 28, 1973

Prologue

All history, granted a wide enough perspective, is merely irony. In the paleozoic era, New Burlington, Ohio, was very largely limestone, at the bottom of the sea. Later, it was forest: the durable oak, the sweet maple, the sassafras, hornbeam and buckeye. Still later, in the last days of New Burlington itself, when the waters of Caesar’s Creek flooded into the village’s only cross streets one final time, farmer Phil Hartman drove his powerboat across the bottomlands towing his young son on water skis. The boy slalomed over Bill Conklin’s submerged fence posts and up into New Burlington, where he landed in 90-year-old Merle McIntire’s peony bed. Three generations down, five-year-old Gregg McIntire watched both the water and the Hartmans and suggested to Grandmother Merle that she not move from New Burlington as the Army Corps of Engineers demanded, rather remain and open a bait shop on her back porch which overlooked the Caesar’s Creek bottomlands. Gregg’s mother, thinking this like him, laughed. Merle McIntire did not. Unsuccessful at willing herself to die, she soon met the corps’ deadline, and moved into a trailer park. The mollusca (whose shells provided the benevolent organic sediment basic to limestone) had given way to the McIntires, who in unyielding turn, were giving way to the return of the water. And the Hartmans, in an unwitting betrayal of their stricken village, became the first pleasure-seekers of the Caesar’s Creek Reservoir.

Genesis

The farming country of southwest Ohio is practical country, made in the image of man. Two hundred years ago, before the imposition of image, its land was more aesthetically pleasing, but that is a poet’s judgment and not a farmer’s. In the time of the great forests, the land of what was to become New Burlington, Ohio, sloped from the east a gentle mile, more from the west, and came together where two streams bent in a wishbone. In the early 1800’s, settlers deserted their thin topsoil on weak eastern hillsides and moved west to Ohio where with an imponderable labor they shoved the forest back and planted grain on its rich, newly domestic floor.

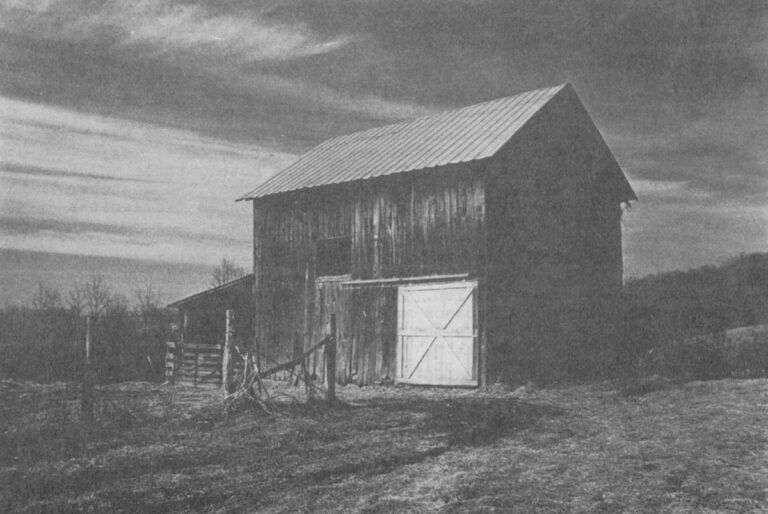

Moses McKay, following rumor, brought his 11 children from Virginia in 1818. The son named Francis drove the plough horses. The others came by flatboat, bringing cold coin to buy 1600 acres at $3 an acre. Massie Hawkins came on horseback, carrying a pear tree. And when the forests were subdued, there was still terror in the land. In the uncompromising winters, the fields bare of crops, the land spun toward the horizon and rushed on forever. The farm buildings were held to the earth with silence and darkness, fragile clusters on the end of long tethers of lane cutting across cleared ground. There were miles between them, candles and kerosene wicks making an uneasy truce with the night, pressing in from every direction.

Sarah Haydock, the cobbler’s daughter, feared the night. “On the farm, I could not see out because of the dark and every week the news saying ‘There’s robbery in the park.’ I was always so fearful. I do not know where such fright came from. It was always there. Once, a gypsy told my fortune. She took my right hand and said, ‘I see letters an inch high. They spell F-E-A-R.’ When my mother was five, about 1853, they used only candles. Grandmother Morris rode sidesaddle to John Grant’s store in New Burlington and brought home the first coal oil lamp anyone had ever seen. ‘Stand back,’ my grandmother said as she prepared to light the match. ‘I’ve seen it done, but I don’t know about it.’ My mother cried. Then the match was scratched and the lamp lit up the darkness and they were so happy.”

Spring, too, dispelled the terror. Spring returned the land to its rightful owners. Spring chased down winter when, as Sarah Haydock recalls, “men sat in their kitchens with their greatcoats on.” Crops exploded in the fields in the spring, and new corn began to color the vast empty spaces. When cobbler Thomas Haydock found barn carpenter William Wood looking from the rear window of his shoe shop, suspended deep in some private reverie, he watched him for a time.

Photos by Barry Dillon

“You’ve traveled, sir,” he said finally. “And where does the best land in the country lie?”

“Anderson’s Fork bottoms, sir,” answered William Wood, not turning from his view across the bottomlands. “Anderson’s Fork bottoms…”

Community leavened the flatland silences. A village grew in the wishbone of the streams. In the 1880’s, wounds of war healed, the village dead tucked with ceremony into the high and waiting ground to the east, New Burlington, Ohio, was: one sawmill, two churches, one school, one hotel, three groceries, one wagon shop, two dry goods stores, two doctors, one carpenter, one cobbler, one undertaker, three blacksmiths and one chicken thief. Population: four hundred.

The bell on top of the hotel was good bell metal (not cast iron), the water from the village pump was cold and sweet, the bottomlands rich. The maple gave sugar water in the fading winter, the black walnut and hard wood transferred man’s subtle kinship with the woodlands into the beams of his home. Good wood, good faith. The continuum of all things was not yet broken. The hand still controlled the plow stock, the ax and the awl. There was still symmetry in the land, even if by the grace of that declining ratio of what remained untouched to what did not.

Shortly after the beginning of the new century, Sarah Haydock the cobbler’s daughter, married Edwin Shidaker, a farmer of Swiss-German descent, and became Sarah Shidaker, farm wife. Farming, she found, was more than a work, it was how a person lived. It rode you through the days on the spur of its demands: you shared its heat and cold and in its good years, its crops. You were always tenant in a changing house, and if there was disaster in such permutations of the season, then there was also an elemental connection with the origins of all living things. The symmetry remained.

“There are just three things in life,” asserted Sarah Shidaker, “animal, vegetable and mineral. They are all found in the country. Few of them are found under a city’s concrete. They say a tree grows in Brooklyn, you know. ‘A’ means one. One tree. How I loved the farm! We planted corn after the grubworms hatched out and flew away. Then we knew it was warm enough. We planted clover seed under the dark of the moon in March when the ground was honeycombed with ice. Sow oats in the mud, it is said, and wheat in the dust and plant beans when the moon is so-and-so or they’ll be all vine and no beans. Well, there were desperate heartaches, too, with the hail riddling the crops, and the wind, and the corn suffering for the rain. How we prayed for rain, only to turn around and pray for it to stop when we were in the mud. Man proposes, you know. God disposes. The eye of The Master fattens the cattle. Once we lived that way. We were in no big hurry, then things got too fast because we began riding fast, and in every direction. ‘Sarah,’ my aunt said, ‘don’t ever get in an automobile.’ I said, ‘Why, I wouldn’t think of it.’ I was never in an automobile with a young chap in my life but later I attempted to drive but never learned it properly. I was too fearful. But no farmer wants to go back to a team to turn his furrows, and a housewife would rather have a Mixmaster than a crock and a spoon. But there was something warm there that I do not have today. We’re living on the earth, but in a different way and now everything is taken care of but death. We know how to avoid birth, but we still die. All things end, somehow or another. Turn backward, O time in your flight and I’d live you differently! There are some things I’d omit and others I’d have just a little more of. Now I am old, and on stairsteps. I show my 90 years of life. Sometimes I don’t wave at my nearest and dearest for watching my step, which shows me the poverty of my feet. I am the last leaf on the tree, and I believe I am outliving everyone else. I am alone in a strange world now. So many people work strange ways and there are no more Sundays and no more nights and I wonder: where will my grandchildren have their potato patches…?”

In the late ‘30’s, electricity came to the village. A traveling man came to do the work, and boarded on a nearby farm and milked a cow to pay his keep. When the village had been wired — at least those homes which sought such an inconceivable entry into the first vigorous stirrings of a modern alchemy – curious neighbors gathered outside a lower Burlington home and watched a porch light switched on, and saw the darkness shaken as if it had been something fine and fragile and could now, by the simple twist of a crude switch, be broken and crumbled to a quiet dust. Darkness could be reckoned with. The sinister corners of long winter nights were rounded. Sarah Shidaker felt inexplicably joyous. If new light dispelled old mystery, then she preferred it.

No one denied the severity of change, but only the village eccentric — who refused electricity and, some years later, the carpeting of his wooden floors — cried out incoherent sentences about poison in the walls. At the wishbone of the streams, the blacksmith stood in front of his shop and remembered stories of the old ones who had feared the iron plow would poison the soil for crops, and that the change from wooden peg to iron nail would damage the building. But madness is often metaphor. Could it be that the severity of change was genetic? Would Sarah’s grandchildren suffer from an unknown chemistry? But these were faint whisperings. Progress was in the air. The common elements were about to be converted to the gold of a thousand imaginings, and instinct had an easy price.

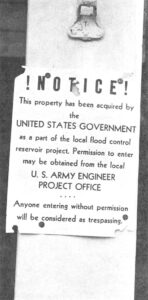

It was in the ‘30’s, too, that the Army Corps of Engineers first came to New Burlington. The intrusion was complete, but unrecognizeable, because the great but dumb roll of the times said: there is no more fear. There is no more mystery. Provision has been made. And so the disrupting psychology was set.

A surveyor came with his tripod, set up business in a field where grain grew, looked through the eye of his equipment, and found what he saw fertile for his clever work. At a window, there appeared the face of a printer’s wife, and a hand holding back the edge of a starched curtain. “I wonder who that is?”’ she asked, turning away with suspicion. That night at dinner she mentioned the intruder. Eventually, rumors moved from house to house, and in the persistence of rumor, which remained for years at the passive level of speculation, the people forgot the initial alarm of the first woman at the curtain. She herself forgot that her fingers had strained the starched curtain in that initial moment of panic. Poachers! her brain said. But dinner was on, and cattle waited with full udders.

So the town accepted the rumor, assimilated it into itself, and lived on, vaguely worried, the demanding moment absorbed by time and duty.

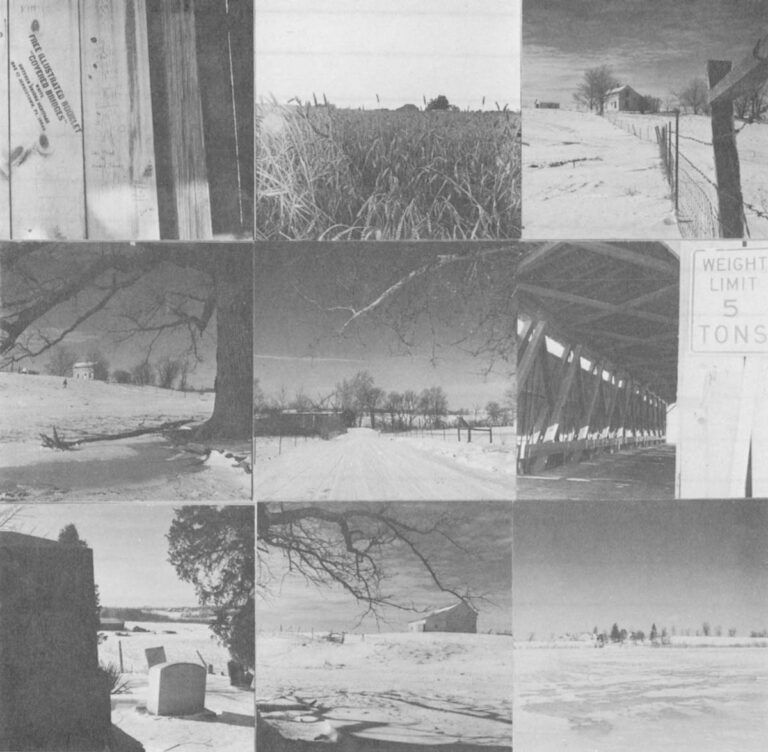

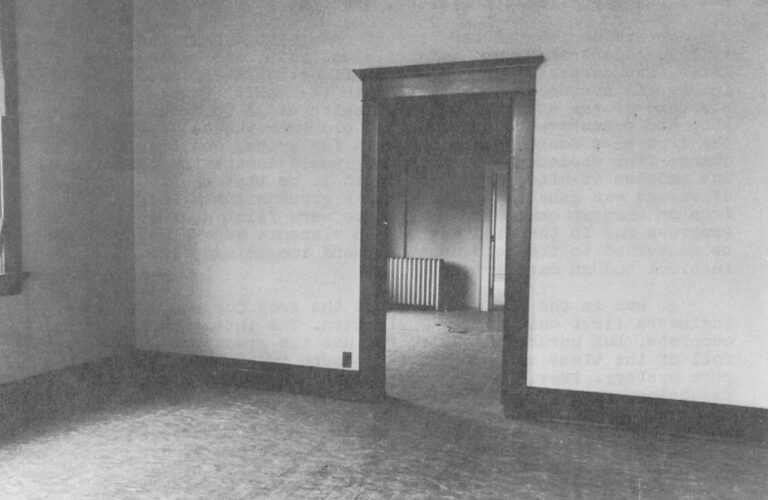

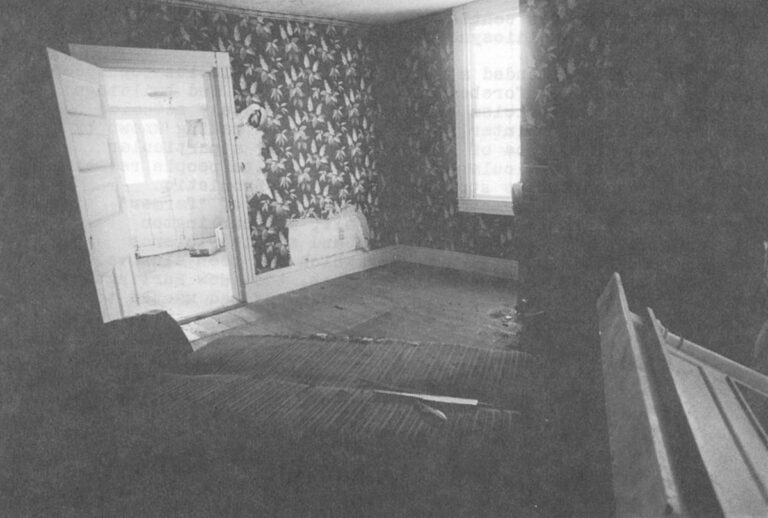

New Burlington, Ohio, is deserted now; that is to say, the people have gone. And during the harsh winter when the land turned inward upon itself, sheathing itself in ice, making its own bones go stiff, it seemed that the town and land had conspired to entomb the town’s passing in mystery. But as spring foliage wraps around the few remaining houses like bed covers, while glassless windows look as dark as the pupil of the eye, New Burlington seems still to be alive.

If its remaining life is symbolic, its last spring not rebirth but summation before death, that fact is now a challenge. Like the work of art released from the fury of the artist and declared finished, the town, its effect on its people, the method of the fatal wound, all stand released for appraisal. The process of summation is a manifestation of the tragic fact that we learn values from things lost, ourselves the wounded and the healer, caught between pain and prognosis. The town looks mean .

Ken Steinhoff

The story of New Burlington is an explanation of that meanness and the depth of the challenge it made, a stern overseer of its own last rights in a time used to the facile incantations against the polluters. The language of the ecologist did not satisfy. It was not enough to say a town and its land rich with grain and trees and wild life was being destroyed because the Army Corps of Engineers had not understood the value of land and the people who knew it.

No, that eulogy was sentimental, and did not record the complexities, the idiosyncrasies, the history of the town.

New Burlington demanded a different justice. If its townspeople appeared stoic and forebearant, if its houses and buildings contrasted that stoicism by standing shamelessly revealed in the thawing of winter, then the town was making known by the essential absence of grace its need for a particular summation: its particular history retold, its people revealed as rounded characters stripped of the anachronistic sentimentality which accompanies the labels of “farmer” and “country people.” And most of all, New Burlington demanded a naming of the contained and subtle violence which brought its death, a naming which had been elusive. Why? It demanded an accounting of that, too. New Burlington had, simply, not known enough of itself and had wanted to.

Received in New York on March 7, 1973

©1973 By John Baskin

John Baskin, on leave from the Wilmington News-Journal, Wilmington, Ohio, is an Alicia Patterson Foundation Fellow, supported by a Ford Foundation grant. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Baskin, the News-Journal, the Ford Foundation, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.