They, being commonly out of doors, heard whatever was in the wind.

– Thoreau, Walden

In the summer, the cornfields surround New Burlington with a startling density. In early August of a wet year, the stalks climb until the roads into the village disappear. Farm houses mire in a seasonal forest: green shingles, green stalks, green thoughts. In late August the silken plume on the ear darkens. The earth tilts under harvest weight. Frank Lundy’s heart leaps on green August mornings. Form and function meet in such dark bottomlands. The road that rises to the graveyard hill is east and west, but Frank Lundy’s corn rows run north and south. “You can drive by and look down the rows,” he explains. “I thought I could plow as straight a row as anybody in the country, you see. It showed well running north and south, gave a different look to the field, and made a very pretty picture. They would say at the bank: ‘I saw your cornfield….”

His neighbor to the east, Albert McKay, shares his affinity for good corn in straight rows. They are bound, of course, by the country ethics of proximity, and the weight of history on their land. Frank Lundy’s bottomlands have been in two families since the first white men came to survey it as spoils of the Revolutionary War. Indians ate corn from the early fields. Thomas Haydock hid among the rows the night he ran away to join the Union army in the 1860’s. McKay land has always been McKay land. But mostly they, as the men nearby, where the same families have farmed uninterrupted for the better part of two hundred years, are bound by their fields. If one of Frank Lundy’s neighbors chides him about painting only the two sides of his barn visible from the road, this is temporal gossip. The fortunes of the bottomlands reveal Frank Lundy’s true character. Everything is known by the fields. The men mark them with their plows; in return the fields mark the men with their more profound demands. Albert McKay began in the fields in 1907.

“My father,” he remembers, “wanted to see how stout I was. I was 10, and he left me to put out two acres of corn with a two-horse plow in an alfalfa field. The hired man showed me how. The alfalfa roots were as big as your thumb. The plow fairly vibrated. Roots snapped around me like a dry brush fire. I ran the plow under a root, finding it very hard to bear down on the handles to raise the tip because I was 10. There I was, yelling ‘Get up there! Get up there!’ in my tiny soprano voice. I had to come home for the ax and cut my way through. It was new ground, and I cut it. It wasn’t a very thick stand, but it was awful good-eared corn. I got seventy bushels to the acre.”

There were tides in the deep cornfields at the end of summer, giving the fields at times a strange surface life. Sometimes, under the moon, the leaves moved when no wind was felt. At such a time, the fragile and elementary processes accentuated by the silken, mysterious night, Albert McKay stood in his fields and felt his feet root into the dark soil. His blood hummed in the thick veins of his arms. The weariness lifted. He felt that he and his horses could go on forever.

The vitality of a good horse infused the plowman. The clean energy of a straight row put creation in the earth below. A good harvest fed the plowman’s family. The cycle was complete, disregarding, of course, what farm wife Sarah Haydock Shidaker, the cobbler’s daughter, called “the disposition of the Almighty.” No one had a clearer eye than Sarah Shidaker for the ambiguity of the seasons: “We planted corn after the grubworms hatched out and flew away. Then we knew it was warm enough. We planted clover seed under the dark of the moon in March when the ground was honeycombed with ice. Sow oats in the mud, it is said, and wheat in the dust and plant beans when the moon is so-and-so or they will be all vine and no beans. Well, there were desperate heartaches, too, with the hail riddling the crops, and the wind, and the corn suffering for the rain. How we prayed for rain, only to turn around and pray for it to stop when we were in the mud. Man proposes, you know. God disposes. The eye of The Master fattens the cattle. Once we lived that way…”

I could let my team go halfway down a 40-shock field -- a shock was 12 steps, a corn shock, and you measured that way because when you paid help you paid by the shock and sometimes if you weren’t a little careful there was more shocks than was supposed to be because some of the fellows tended to get a little short-legged late in the day. And I let my team go and I stood and talked over the fence. This country has changed right smart to say the least. I cut once 14 shocks of wheat next to the creek, helped fill two silos, and milked twice. By the time I got the second milking done, I was awful sorry I only got in twenty hours. I didn’t know what to do with the rest of the day so I just went to bed. I used to say to myself: I’ll do that at any cost. If it was something I hadn’t got done by dark, why, if I could see any at all, I just went ahead and did it. I never heard of a forty-hour week until I was old. When my uncle got old, he went to the garden with a high chair and a hoe. He sat in it, hoed around him, then moved the chair and hoed some more…

– Albert McKay

But between man, beast, and the land they both shared, there were not severe differences although these differences would come. For the moment, each bore the eccentricities of the other. The horse lived beside the plowman, both in equal proximity to the heretical seasons. The horse fastened the plowman to the floors of his fields, a link of the living to the living. The horse had human characteristics; the human could twist imperceptibly and assume the traits of his livestock. Sometimes the behavior shifted silently between man and beast until all origins were obscure. Said one farmer: “They don’t call it stubborness when a mule has got it.” One of Albert McKay’s best horses was a blind Percheron mare, who ran away with the manure spreader. The mule, Maude, brayed in the fields at noon. “All had their characters and you had to remember that. I had to know them like my boys, what they would do and what they wouldn’t. I had a black mule who didn’t like ditches. Hitch him on the ditch side and he would crowd over. I threw pebbles at old Mike, my lead horse, when he misbehaved. As he was lazy, he sometimes required a good many pebbles.

But between man, beast, and the land they both shared, there were not severe differences although these differences would come. For the moment, each bore the eccentricities of the other. The horse lived beside the plowman, both in equal proximity to the heretical seasons. The horse fastened the plowman to the floors of his fields, a link of the living to the living. The horse had human characteristics; the human could twist imperceptibly and assume the traits of his livestock. Sometimes the behavior shifted silently between man and beast until all origins were obscure. Said one farmer: “They don’t call it stubborness when a mule has got it.” One of Albert McKay’s best horses was a blind Percheron mare, who ran away with the manure spreader. The mule, Maude, brayed in the fields at noon. “All had their characters and you had to remember that. I had to know them like my boys, what they would do and what they wouldn’t. I had a black mule who didn’t like ditches. Hitch him on the ditch side and he would crowd over. I threw pebbles at old Mike, my lead horse, when he misbehaved. As he was lazy, he sometimes required a good many pebbles.

“And how I liked my walking plow! Yah! Woah! Get in that furry! Gee-up! That old auger plow threw the dirt. When I got a gang plow — two plows, 14 inches, five horses — I thought I had made it. I could stay out until dark and cut five acres. I put out a hundred acres of corn and thought I had a dickens of a crop.”

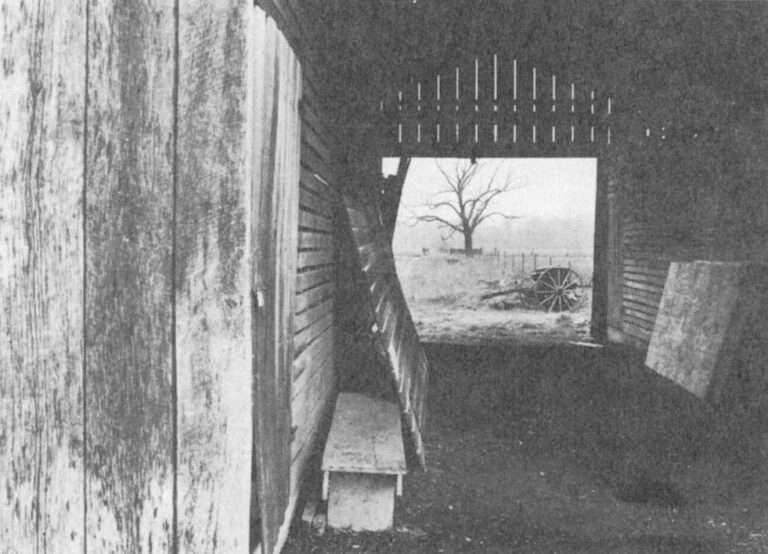

Frank Lundy’s bottomlands were nearly the same size. He kept his horses forever. He quit plowing at six o’clock and left the fields for supper. After supper, he sat on the fence and watched his livestock eat. It gave him an inexplicable satisfaction, although his wife stewed mildy in the kitchen at such misplaced devotion. It seemed at times that all the sounds flowed together into a stately music such as he had never heard before. He was surrounded by a thousand living things. The barn expanded with the heat from his horses’ bodies. The hogs crowded together while eating and in the growing dark became a single vast low beast spreading across the yards. The cicadas screamed in the grass. He sometimes thought he could hear the corn pushing its way through the earth.

There were still discreet proportions to the world. In the fields, drugged by the rising sweetness of fresh cut earth, Albert McKay could look to the ends of his land and over the curvature of the earth itself. Everything was revealed. “A day,” said Albert McKay, “was as long as the Lord made it. The Lord made the days then. Walter Lackey was running a threshing machine in the summer and the women called him to dinner before he was ready. After he ate he said, ‘The women made the forenoon but God Almighty will make the afternoon.’ And he worked until dark.”

The McKay geneology ran through the farmhouse and over the countryside, filled with the living McKays, and into the graveyard, filled with the legendary McKays. It even ran into the nearby fields where Albert’s maiden great-aunts lay buried under the corn, although the tombstones had since been removed to the graveyard on the hill above the village. The farmhouse was built in the last year of the Civil War by one grandfather, the village road out front by the other.

If the nature of all things is largely accidental, then there was a time when it was less accidental. The gravity of the earth extends outward as well as downward. It pulls all things toward it. Who, then, should feel such incalculable physics more than the plowman’s sons? There were five boys and two girls in Calvin J. Lundy’s house. When asked how many boys in that tangled crop of humanity in his yard, Calvin J. replied, “Thirty feet, six inches,” which was fine and precise since the word Lundy itself meant “size.” One son became a carpenter. Another became a teacher. One went to town, watched by Frank, uncertain in the voluminous space of radical seasons. “I didn’t like the way he had to do,” said Frank finally, and simply. But the implication had its own resonance: if all things suggest bondage, name the terms of bondage. The malfeasance of nature offers both casualty and charity. Unpredictability can be virtue; it can feel free. The narrowness of option and the gravity of the fields aided Frank Lundy’s selection. “Farming,” he said, “is all there is.” The vow of country asceticism taken, he began with three horses. In 1925 he rented some ground for wheat and kept close records. Calvin J. snorted at such manifest folly: “You’re not supposed to keep records,” he told his son. “Take what you can and forget it.” But the simple substance of Calvin Lundy’s time was becoming airy and spectral. There was complicated new government and intricate machinery about. Perhaps Calvin Lundy and Clarence McKay could go through a new time with old physics. But surely their sons could not.

(Next: The Coming of Machinery)

Received in New York on September 12, 1973

©1973 John Baskin

John Baskin, on leave from the Wilmington News-Journal in Wilmington, Ohio, is an Alicia Patterson Foundation Fellow, supported by a Ford Foundation grant. This article may be published with credit to John Baskin, the News-Journal, the Ford Foundation and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.