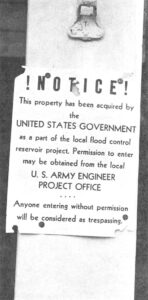

March 15, 1974

John Harlan Pickin’s great-grandfather walked from New Jersey to Ohio when farming country was still new. Caprice being the true nature of human delivery, John Pickin grows older in New Jersey now, and the distance is ever more awesome. He will never return to New Burlington, Ohio, because it is a dying village. Yet New Burlington, condemned in death to even more obscurity than it bore in life, remains the home of John Pickin in that particular way places of the mind and heart transcend all geography.

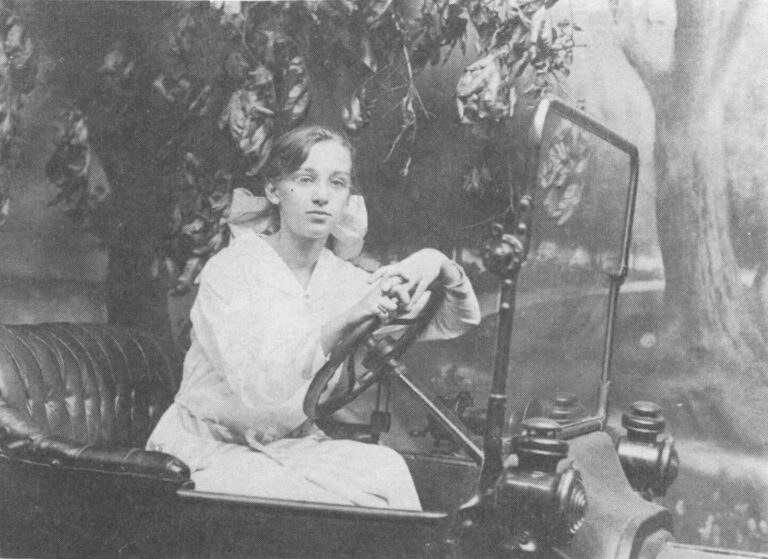

photographs: Sarah Haydock (standing), James Haydock’s granddaughter, fishes in Anderson’s Fork: “Grandfather Haydock always said he was partly born and raised in New Jersey. He told us things today and we laughed tomorrow.” oval photograph is of Sarah’s aunt, Ruth Morgan: “She and my grandmother sat in the window and argued about who passed by on the pavement. It was their form of conversation.” above, Sarah’s niece, Eleanor. “My father,” said Eleanor, “told us that anyone who brought disgrace to the Haydock name would be sent to a convent. I didn’t know what a convent might be but I was properly frightened.” at right, the Haydock family, including Alpheus Harlan with his small son, William. “He looked dignified,” said John Pickin of his grandfather. “He felt dignified. Whether he had the dignity of economics was quite another matter.”

When James Haydock reached New Burlington, he became a tanner, working for hours in chicken manure and human urine up to his elbows. In his century, the great-grandson looked upon the vast stain in the earth where the tannery had been and imagined himself a pioneer. He grew older. Years later, miles away, he found himself subtly but unmistakeably bound to a dying place, to the archaic institution of itself. This is John Pickin’s story:

The First Village Generation:

James Haydock was a bound boy and ran away. He walked to Kentucky and up the Bullskin Trace to New Burlington. He walked past buffalo wallows at the end of Cornstalk Road. His first wife was Catharine Howe from Brimstone Hollow. Proud of her first son, she rode horseback to show the baby to her parents, caught pneumonia and died. The baby that survived was “Uncle John” to my mother. I remember him as an old man with a white beard. The last time I saw him must have been about 1922. He gave me a little cane. Uncle John did not know that Elizabeth, James’ second wife, was not his real mother until he was a big boy and it was a shock. He did not like to be reminded of it. My Aunt Maude remembered him as an old man weeping over his real mother who would forever be only a young girl.

Great-grandfather Haydock’s ambition was to live into the twentieth century, but he missed it two months. For some time he had been in declining health, and occasional drifts of mind. Within a few days of his death, he climbed a tree in his nightshirt. He was 92.

On the Village:

New Burlington was like a medieval society. You were so close. Thrust together. Everybody watched everybody. How could you possibly get out of line? One of the villagers saw a couple of little girls wading in Anderson’s Fork. Two inches of water. ‘I saw their ankles!’ they said. ‘Indecent!’ But such a life causes certain tolerances. If you know all, you forgive all. You met these people every day, face to face. I suppose there was a great deal of hypocrisy. It did not occur to me. The people helped each other. When a neighbor died, his survivors were deluged with cakes. Cakes fairly descended upon them. I still identify with that village. I belong there. My roots are there. From the age of two on, I heard nothing but: this is where we came to, came from. We are of this place. We know every inch of it. I have felt this in England, where my father was from. I was there after World War II, when soldiers were not well regarded. I asked for a place to sleep in a little village called Neots, 17 miles from Cambridge. It was the place of my father’s’ancestry. There had been a John Pickin in every generation for six generations. The innkeeper had no room. ‘Anybody know Pickin?’ I asked in the bar. An old man of 80 said, ‘I once knew a John Pickin…’ Then I was placed in their middle. Harlan, Haydock, you were part of the community. You were the community. It is beyond rationalization.

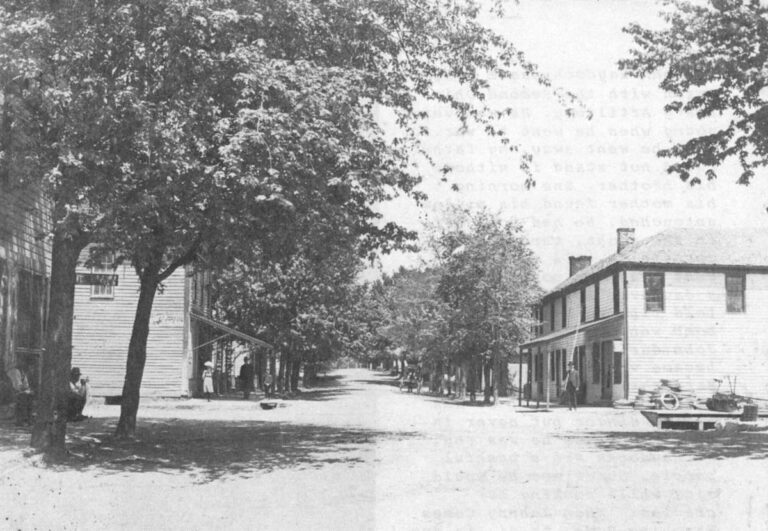

The village cross streets, looking north (above) and south.

On Isolation:

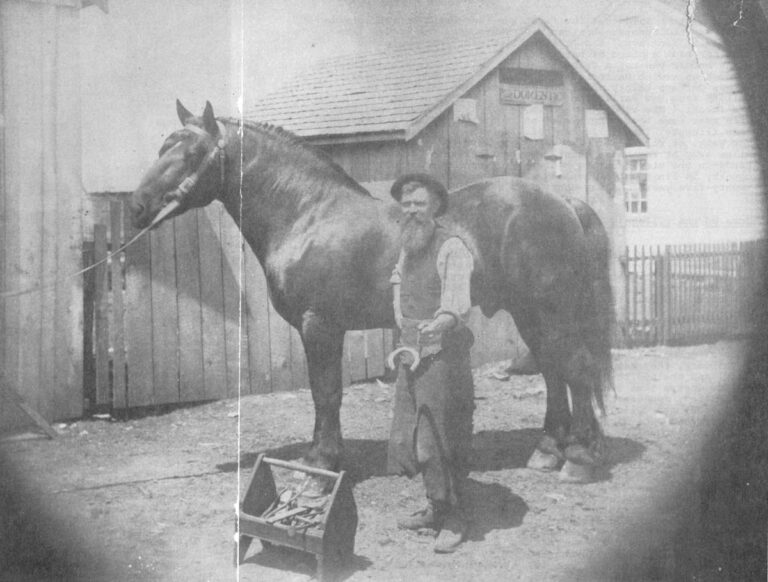

John Haydock was a blacksmith with the Second Ohio Heavy Artillery. He was very young when he went to war. When he went away, my father could not stand it without his brother. One morning his mother found his pillow untouched. He had gone off in the night, through the cornfields. All the boys went away. My poppa wasn’t a day over 15. All the boys told fibs to get there. A bomb went off near Uncle John during the war and he became very deaf. Aunt Margaret found it easier to write notes to him. He was a fine singer but never in public because he was shy. We Haydocks are a bashful people. Sometimes he would sing while rocking our cradles. ‘When Johnny Comes Marching Home, ta di, ta dum.’ I can see him now, shoeing horses. It required a particular way. A light shoe on a driving horse. A heavy shoe on a plough horse. We behaved ourselves nicely and stood out of the way.

— Sarah Shidaker

My grandmother said that the first she remembered of the outside world was the Spanish-American War. There were new words, like ‘Manila,’ ‘Santiago,’ and ‘the Phillippines.’ Her boyfriend sent her back a piece of hardtack. My mother was a grown woman before she met a Catholic. About 1844, Great-grandfather Haydock walked to Dayton to hear Benjamin Harrison at a rally. It was perhaps thirty miles. He came back and said: ‘In walking from New Burlington to Dayton, I was never out of the forest.’ The woods crushed in on all sides. How dreary the life must have been. There were no lights. No radio. A kerosene lamp flickers. Then it is cut off. There is darkness everywhere. You walk, or ride a horse. News? There is a telegraph three miles away at Roxanna. Mother remembers her aunt waving her hands in the street saying, ‘Cleveland won the election! The country is finished!’ Cleveland was the first Democrat in twenty-five years. He was considered wicked.

More On the Village:

Everyone in the village had a descriptive name. There was ‘No’ Evans. He never agreed to anything. Pig-Eye Blair. Guinea Noggle. It showed their Anglo-Saxon origins. The Anglo-Saxons took a person’s worst feature and that became his name. They came and built their houses flush against the streets. Why, when they had the very whole of Ohio, build a house right on the road? They had it this way back in New Jersey where they came from. What you have in the home of your youth, you duplicate later. The county authorities once objected to the cup chained to the town pump. It was unsanitary, they said. So the villagers took it off the pump, and chained it to the wall of the tavern nearby. So how does a town succeed? New Burlington was Quaker, restrained, conservative. Perhaps that inhibited growth. In Dayton, the college and the sciences were associated with the Germanic part of the community. The Anglo-Saxons were anti-intellectual. They stayed out and farmed.

On War:

They brought things up in conversation as if it was momentary. But it was one hundred years ago. All history was collapsed in upon itself. Into this tiny space were all events. Outside events were of…no interest at all. The world went by. The Civil War was the prime topic of conversation. It was refought frequently in Thomas Haydock’s cobbler shop. Until well past 1900, they never talked of anything else. For over forty years. Fifty. If they had had no Civil War, they would have all died of boredom. The Harlans became privates in the war to get away from the village.

They heard about life somewhere else. They would have it. My grandfather, Alpheus Harlan, wanted to go but he was only 13. He was kicked off the train. You could talk out the news of the village in a very short time. It was old stuff quickly. But during the war, they got around. They saw things. Life was dangerous but not dull. In the old house in New Burlington was an attic room. It was dark and filled with things. There was a sword in a scabbard hanging on the wall that belonged to one who never came back. There was a string of tent pegs from some forgotten encampment. On the wall were prints of battles and bits of uniforms and a sword cane one of them had carried when he was down south after the war, during the occupation when folks weren’t friendly still, especially after dark. A beaver hat. A uniform of a type we couldn’t identify. And books. Books of it all. The Civil War had been won by the Ohio Volunteer Infantry and the Army of the West. No one had ever heard of the Army of Potomac. So I always felt close to the Civil War, having sat in a room full of it while of impressionable years.

On Farming:

The Harlans had land but no one wanted to farm. Anything to be in town. No matter how small. For a hundred years there had been a revulsion against farm life. It was too hard. They were leaving in 1800. They were still leaving in 1900. Grandfather Alpheus wouldn’t plant a garden, or touch the soil. He wouldn’t even go into the backyard. He would not work with his hands. The people of the village were largely involved in getting their hands into the soil. Perhaps they disliked him for this. Farm life was hard on everyone. There were horrible stories of people going through manure spreaders, of tractors rearing up and crushing the driver, and ragged cuts that led to lockjaw. My aunt felt sorry for the women because they had no one to talk to. They spent their lives looking at the backside of a cow. She, of course, had the advantages of the village. Farming was very rough. I saw their work. It was an endless labor. ‘Well,’ one said, ‘I canned eight hundred quarts this year but it didn’t match last year!’ I remember the women as bigger. Bulkier. Svelt figures were not desired. There were no sex objects, of course. Sex did not exist. The women made cakes in milk pans. Their recipes began: take thirty eggs….

On Unrest:

You heard these things: he went to Iowa. He went to California. They told each other these things. Get away. Go some place else. In the last half of the century, the intellectual character of the villages changed. At one time, people were well-read. People congregated and held a reasonably high level of conversation. Politics. Philosophy. Religion. I saw their books. In lieu of notary fees, sometimes Grandfather Alpheus took books. The change was that people of ability moved on. First, there were only villages. Then towns grew. There was a railroad. When places grew, people of ability went there. Those who stayed had lesser ambition. Lincoln grew up near Gentryville, Ind., didn’t he? But soon he left. Part of the Harlans did go west. They got through the pass just before the Donner party made it famous. If some of the Harlans had been there, they would have been famous. You heard these things. There was a great urge to move. Someone got through the pass. The word filtered back. They wrote to each other. Boxes of letters. Trying to get the ones at home to move. Make them dissatisfied. Go west, they said. Go anywhere.

On Leaving:

What happened to those who left? Some of them married women who smoked.

On Charles Dickens:

Dickens came through here about the time Great-grandfather Haydock was walking in. He did not think much of James Haydock. He found the country rough, cut off, by no means neat. There were no hedgerows. The fields were not laid out well. Dickens’ biggest complaint was that they made him drink cold water. They gave him nothing civilized to drink. They were boorish. They spit. They were rough, he said, and I expect that was so.

On God:

There were the Quakers midtown and the Methodists uptown. The difference was trifling, of course. The Methodists sang louder. My mother was the first to play a musical instrument in the Quaker church. It was a pump organ. Before that, it had been considered wicked to have any instrument. My aunt went to church and came back saying, ‘Why does the Lord always move her? Why is she always moved?’ She wasn’t moved too often in church herself. She was moved to tell people what was wrong with them. For their own good. This made her very popular. She said, ‘Never forget the golden thread that ties everything together.’ She was very independent. ‘Consult the inner light,’ she said. To hell with the president, anybody. ‘Consult the inner light.’

The Last Village Generation:

Aunt Maude, grandfather Alpheus’ daughter, was quite content with New Burlington. She wanted to be at home. Everything held her to that assumption. She was the reason grandfather didn’t move on, go west, wherever. She would die in the village. She loved the creeks and the fields, and read David Copperfield every year. She made salt-rising bread without yeast or baking powder and mailed it to me in New Jersey. She knew the streams and the runs, little churches and abandoned school houses and forgotten burial grounds. She knew who lived where and who had lived where back and back. She was afraid of only two things, fire and floor. In 1959, the water went to the upper end of the village. It was the worst flood they ever had. Aunt Maude was seriously sick by this time, but she would neither go to a doctor nor have one in. When the water came she refused to leave her home. She was finally carried out under protest. Two days after the flood crested, I flew out and by then the water had subsided and a hard frost had crusted everything, including the coal pile. Aunt Maude had gotten back in the house, had a fire going, and could not be moved. In March, two months later, she took a turn for the worse. She was near death and an ambulance was called to take her to a hospital. She was placed on a stretcher and halfway through the door, she held her arms out straight and they couldn’t get her out short of turning the stretcher and her sideways. They brought her back in and laid her on the couch and she was content. And she died, but in her home and on her own terms.

Received in New York on March 27, 1974

©1974 John Baskin

John Baskin, on leave from the Wilmington News-Journal in Wilmington, Ohio, is an Alicia Patterson Foundation fellow, supported by a Ford Foundation grant. This article may be published with credit to John Baskin, the News-Journal, the Ford Foundation and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.