Maybe a detective lied on the witness stand. Or a prosecutor played games with the evidence. A snitch could have testified falsely after getting a sweet deal on his own case.

Maybe a defense lawyer was incompetent. He even could have been napping in court, as happened in at least one infamous Texas case.

When news breaks about people convicted of crimes they didn’t commit, these are the kinds of transgressions that are usually cited.

Sometimes, though, the wrong person can be convicted of a crime for all the right reasons.

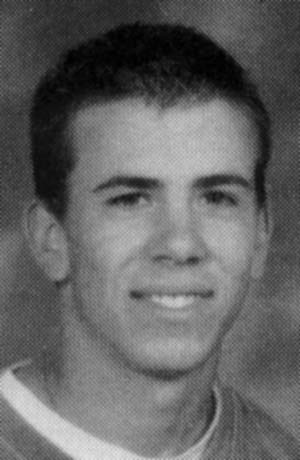

Consider 24-year-old David Jonathan Quindt, who on the afternoon of May 22, 2000 was freed from Sacramento County jail after spending 14 months behind bars for his alleged part in a marijuana home invasion robbery that left one young man dead and a 15-year-old girl critically wounded.

Quindt’s name was given to authorities in part because he traveled in some of the same circles as the real criminals. He also had behaved suspiciously right before and right after the murder. He asked a friend for two guns a few nights before the victim was killed. A few days later, he asked another friend to dump one of the weapons, a shotgun, into the Sacramento River. The other gun, a .380-caliber, the same size as one of the guns used in the crime, already had been taken from Quindt’s house by another friend.

Quindt even was positively identified by the wounded girl, who said she had no doubt it was Quindt who shot her. Before she ever laid eyes on him, her recollections to a police sketch artist resulted in a composite drawing that looked remarkably like him. Once he was targeted, he called detectives and prosecutors regularly to protest his innocence and steer them in different directions. An innocent man might be expected to behave that way but Quindt’s frenetic actions only made him look more guilty.

Anthony Salcedo was a "marijuana broker," the DA alleged in court, who set the whole robbery in motion. Charges against Salcedo were dropped when Quindt was exonerated but evidence showed he had some involvement in the first robbery.

Convicted after a month-long trial of first degree murder, he faced mandatory sentencing to one of California’s most notorious state prisons for the rest of his life, with no chance of parole The legal reckoning for his co-defendant, Anthony Salcedo, who had been facing the same charge, was put off when the judge declared a mistrial. He did so after a witness testified about Salcedo’s past alleged crimes with neither the defense nor prosecution expecting it, ruling that the testimony never should have been allowed because it was too prejudicial toward Salcedo.

A onetime gang member who readily admits his past sins but swears he could never commit murder, Quindt became so overwrought and emotional during his incarceration and trial that he tried to kill himself on several occasions.

He slammed his head into an eighth floor window at the jail. He bit through an electrical cord. He swallowed a pencil. With shackles on while hospitalized for that last act, he jumped through a plate glass window and landed on the pavement, four floors down, and was immediately apprehended. Everyone said his behavior was extremely bizarre.

All this after his girlfriend, Hannah — the mother of his first child, whose name is tattooed on Quindt’s neck — left him a few months following his arrest. He also lost his job and most of his friends. Newspaper and television accounts portrayed him as a callous killer.

“My brain was just jarred,” he said in a recent interview. “I was so stressed my gums started bleeding. Everyone thought I was a murderer. In the DA’s office, everyone was saying, ‘You did this. You did this.’ It shocked the hell out of me. No one believed what I was telling them. Finally I snapped out of it. I just started reading the bible and worked on my case. I couldn’t believe this was happening to me.”

There were plenty of good reasons Quindt became a suspect, as will become clear as his story unfolds. But his nightmare took many bizarre twists and turns that cannot be explained so easily. And although he is back to work, married and has a new baby girl, the story has yet to play out fully in Sacramento County Superior Court.

A new set of defendants who were unknown to detectives and prosecutors until after Quindt’s conviction will face trial soon for murder in a case that the same deputy district attorney must delicately shepherd through the system. A key witness against the man now believed to be one of the shooters is that man’s sister. She eventually admitted that she was told of the murder early on by her now ex-husband, who is also one of the new defendants.

Lupe Trujillo has promised to testify against both men, after being consumed by her secret for more than a year. But homicide prosecutor Mark Curry still worries she may “go sideways” because Curry won’t grant the family’s wish to show her brother, David, who turned 20 the night of the murder, much leniency. If she does testify and her brother and ex-husband are convicted, they, too, are likely to face life in prison without parole, although Curry has said his office might be willing to offer Trujillo 40 years to life, which means he would be eligible to apply for parole after serving 34 years.

“I have nothing against the DA. He was just doing his job,” Quindt said recently, but he has hired one of the top lawyers in town to sue the county and the public defender who represented him.

Then there is the family of Riley Haeling, the 18-year-old murder victim. Judy Haeling, his mother, feels compelled to sit through another painful and heart-breaking trial.

“I have no choice,” she said after a court appearance last spring. “If they are talking about my son, I just feel that I need to be there and hear it. I do not want to go through this again. It was so gut-wrenching the first time, but I had gotten used to the idea that the people on trial were the people responsible.”

For Quindt, nicknamed Sylvester because as a kid he liked to draw pictures of the cartoon cat, his descent into criminal justice hell began the afternoon of Oct. 5, 1998 on a suburban street in Sacramento with the exotic name of Maui Way. A winding lane of towering palms and stucco ranch houses, it could stand in for any sun-swept California street. Hardworking men and women raise their families there and enjoy the fruits of their labor with backyard barbecues or outings on the occasional boat parked in the driveway.

In one such beige stucco house in the middle of the block, however, much more was going on. Daniel Salmon and his family were growing high-grade pot in a backyard the Harley Davidson enthusiast protected with a barbed-wire fence, a wooden gate lined with protruding nails, and video surveillance cameras. In one bedroom of the house that he lived in for more than 20 years, police reports say he kept a half dozen shotguns.

Salmon and his 17-year-old son, Danny Jr., said they had a doctor’s prescription to grow and smoke pot to relieve chronic pain from assorted ailments. But a number of kids at Danny’s nearby Bella Vista High School told sheriff’s detectives they also considered the house a dope haven. It was the place to go, they said, when they wanted to smoke or buy pot. They called it “chronic” or “bomb weed” for its extra high potency. Everyone in the school’s so-called dope crowd seemed to know about the house and its valuable crop.

In Sacramento’s typically cool and dry October, the 18 to 20 plants in the Salmon yard were fat and moist with buds and resin. It was the perfect time for harvest.

The Salmon family’s two kids, 15-year-old Jennifer and Danny, smoked pot frequently, according to police and court testimony. The family even traveled to Jamaica for a marijuana festival, and there had been several prior attempts to break into the house and steal some of the Salmon’s bounty. One friend became so concerned with talk at a party about robbing the place he went to Jennifer with the news and told her to beware.

Police said that at various times there was enough marijuana growing in the yard to fetch $100,000 in street sales, though the Salmons insisted they grew it solely for their personal use and never sold any of it.

On the afternoon of Oct. 5, 1998, Danny Jr., and a friend from school, Justin Taylor, were home around 2 p.m. They were sitting by the backyard pool, tending to the plants and pruning some of their leaves, when three men wearing surgical masks kicked in the front door yelling, “Police! Police!”

Danny said he waited and watched through a living room window as the men rummaged around in the house before heading to the yard. Justin, believing this was a police raid and that the pot was being grown illegally, said he hopped the fence and fled.

As one of the intruders crouched down to inspect the plants, Danny came up behind him and hit him with a metal pole used to clean the swimming pool. That’s when a man later identified by police as Joshua Kalb, then 19, who had driven the group over to the house in his purple Thunderbird, smacked Danny in the head with a baseball bat.

“As soon as I saw him go over to the plants, I knew I had to do something,” Danny later told Sheriff’s Detective Dave Wright. “I couldn’t just let it happen. I should have just let him take the plants and say to him, ‘Is this all you want?’ But I didn’t. Instead, I hit him with the pole. That’s when I got hit.”

After the men left, Danny, who went into a coma and suffered serious head injuries, staggered to the street. Justin spotted Danny sitting with his head in his hands and bleeding from his right ear. He couldn’t talk and drifted in and out of consciousness. Danny was able to ask Justin to call Danny’s mother, who is a nurse.

While getting Danny to a nearby hospital, Justin also used his cell phone to call Riley Haeling, his best friend. Riley was a sweet-faced 18-year-old kid who overcame dyslexia to graduate a year earlier from Bella Vista. He was working with younger disabled kids at a special school and had plans to attend college so he could one day open a similar haven for disabled children and run it himself.

A few hours after the first robbery, with Danny’s sister, Jennifer, now home and Riley and Justin back from the hospital, the three dug up the remaining pot plants. At Jennifer’s father’s request, according to sheriff’s investigative reports, they drove them to a friend’s house. When sheriff’s deputies showed up, Jennifer and Danny’s friends told them that they had found a dazed and badly beaten Danny sitting in the street, a few blocks from his house. That’s where the attack occurred, they said. Jennifer explained later that she figured police wouldn’t be in a position to question the family about the pot if they thought the crime occurred elsewhere.

This turned out to be deadly deception because police did not tape off the house as a crime scene. The family was free to return as soon as it wanted.

Later, under a cloudless night sky and a full moon, after checking on Danny at the hospital, Daniel Sr., Riley, Jennifer, Justin and another friend went back to the Salmons’ house to eat dinner and watch television. Danny’s mother stayed at his bedside.

Daniel Sr., got a call to return to the hospital almost as soon as he made it in the door. Jennifer said she was too worn out to go. So Daniel Sr., asked Riley, Justin and another friend, Shawn Pollard, if they would stick around and keep an eye on Jennifer until they returned. Sure, they said, they’d spend the night. Don’t worry about a thing.

“He called and said Danny got beat up and he was going to spend the night,” Riley’s mother said of the last conversation she had with her son. “I said to him, ‘Isn’t that dangerous?’ and he said to me, ‘Mom, would I stay if it was dangerous?’ I didn’t like the idea but he was not a foolhardy kid.”

A few other people were at the house, but they left after watching Monday Night Football. At 2:30 the following morning, with Jennifer and Riley having fallen asleep on a living room couch while watching movies on HBO, the rich crop of pot attracted another set of thieves. The door was easier to open this time because it was busted from the first robbery.

This time, though, the three men who burst into the house — it would be months before anyone learned the connection between the two separate sets of robbers–had guns. They pointed them at Riley and Jennifer as they were awakened by the noise.

“Where’s it at? Where’s the dope?” they demanded. One of the men went to see if anyone was in a back bedroom. Shawn had gone to sleep there and tried to reach for one of the Salmons’ shotguns but the gunman immediately opened fire.

Shawn told detectives he fell to the floor, pretending to be hit. That’s when everything went nuts.

One of the other intruders had been pointing his gun at Riley and Jennifer, demanding to know where the dope was. When he heard shots from the bedroom, he fired six times. The gunman in the back came out firing, too.

“Did ya get ‘em dog? Did ya get ‘em,” Jennifer heard them say. She had been hit once in the leg and once near her navel.

Riley, who Jennifer said jumped on top of her to shield her as soon as the men started firing, was hit five times. All of the bullets recovered from his body were .380-caliber. One round hit Riley in the right side of his chest and burrowed through his diaphragm, heart and lungs. That was the one that killed him. A 9mm bullet was recovered from the couch and 9mm shell casings were found on the floor.

In the Sacramento Bee the next morning, Riley was hailed as a hero for protecting Jennifer from some of the shots that were fired.

His mother, meanwhile, in what only could be described as tragic irony, found under her front door mat, two Jimmy Buffet tickets that a friend of Riley’s had dropped off for him so he could go to the performance of his favorite pop artist at Shoreline Amphitheater in the Bay Area. She found them that morning after a police chaplain woke her in the middle of the night to say that her son had been killed.

It was a high profile murder with reams of press and television coverage — more than 300 people attended Riley’s funeral — and detectives made the case a priority. But after several months chasing down one bad lead after another emanating from the shadowy drug world that is part of most urban high schools, no arrests were made.

Then David Quindt’s name surfaced. Quindt, a punk who helped start a local gang that called itself the Instigators and was known for beating on outsiders who acted tough in their suburban Sacramento neighborhood, had asked a friend on the night before Haeling was murdered to get him some guns. He eventually told detectives he wanted them for protection because one of his gang buddies had been shot a few days earlier.

The friend, John Anderson, said he gave Quindt and a friend of Quindt’s, Anthony “T.J.” Salcedo, a shotgun and a .380-caliber handgun. And as it turned out, the day after the killing, when it was the lead story on all the television newscasts, Quindt asked another friend to dispose of the guns and not breathe a word about it to anyone. Anderson also told detectives he bought some “wet weed” from Salcedo — pot that had been picked but not yet dried — right after news of the killing broke. Detectives immediately tied the men to the crimes.

About the same time detectives were finding all this out, Jennifer Salmon was giving a sheriff’s sketch artist details of the man who shot her. But her recollection may have been influenced by Anderson having told her while she was recuperating in the hospital that the shooter she described to him sounded a lot like this guy he knew from around town, a guy by the name of David Quindt.

He was tall and skinny with a dark complexion and scraggly hair on a long, thin face, the friend told her. The sketch was circulated and Quindt was questioned a number of times. He acted suspiciously by calling detectives repeatedly to protest his innocence and to grill them on what they knew or to suggest new leads for them to check out.

In mid-February of 1999 — more than four months after Haeling was killed — detectives arrested Quindt, who worked at an equipment and tool rental firm, and Salcedo, still a student at Bella Vista. They presented their evidence to the district attorney’s office and each man was charged with first degree murder.

“He shot because he was angry,” Curry told a jury when his case against Quindt came to trial the following November. Angry because he couldn’t find the marijuana someone connected with the first set of thieves told him would be there for the taking.

“Therein lies the motive for both of these crimes,” Curry told the jury. “It is over money.”

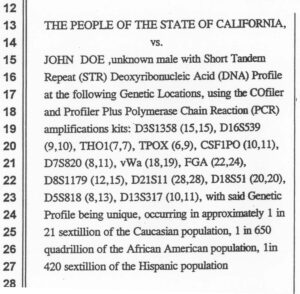

Curry, one of the most respected prosecutors in the district attorney’s office, was so confident Quindt was his man that he posted the composite drawing next to the jury during his closing argument. On Dec. 2, 1999, the jury came back after deliberating for three days and gave Curry what he wanted: a guilty verdict against Quindt.

Quindt cried out, “Oh, God.” He dropped his head into his hands.

Dozens of friends and family members of Riley Haeling cried, too, saying nothing would bring Riley back but that justice had been served. Curry walked out of the courtroom with a big black satchel of papers and files. A press release was prepared. The DA had won another one.

It was a few weeks before Christmas. Curry was exhausted from another tough trial and was looking forward to a quiet holiday with his wife and two small kids. Feeling good about the case, he would get a call in a few days that would turn his world — and the world of more than a dozen other people — upside down.

©2002Gary Delsohn

Gary Delsohn, a reporter with the Sacramento Bee, is examining the workings of an urban District Attorney’s office.