The Christmas holidays were over and so was his last big murder trial. Veteran homicide prosecutor Mark Curry was cleaning up the clutter in his small office near the county courthouse when the phone rang. It would have been easier to let his answering machine pick up, but something told him to take the call.

“Hey Curry, remember me. This is Brian Lutz,” the caller said. It didn’t take long for Curry, a deputy district attorney in Sacramento, CA, to place the name or voice. Lutz was a thin, 20-year-old kid with ratty blond hair, a runny nose and no end of small-time problems with the law.

But Lutz had been useful in the past, providing crucial information about a 1996 murder committed by friends who trusted him to ditch the murder weapon, a 9 mm pistol. When cops found the gun in Lutz’s house and threatened to charge him with accessory to murder after the fact, he opted to testify against his friends in a case Curry prosecuted.

Now Lutz had read about a $10,000 reward offered by the family of Riley Haeling, an 18-year-old shot to death when thieves broke into a house he was spending the night at to steal what they thought would be a bounty of high-potency marijuana plants.

In early December, Curry had won a first-degree murder conviction in the heavily publicized case against David Quindt, a then-21-year-old employee of an equipment rental firm who once belonged to a suburban Sacramento gang known as The Instigators. An alleged accomplice, Anthony Salcedo, who was then 17, was to stand trial following Quindt’s conviction. In early court sessions, Curry called Salcedo a “marijuana broker.”

Police said Haeling was an innocent bystander who was staying at the house. The owners, Daniel Salmon and his wife, were at a nearby hospital at the time attending to their son, Danny Jr., a friend of Haeling’s. He’d been hit in the head with a baseball bat during a robbery at the house the afternoon before Haeling was shot five times and killed. Police said Haeling died a hero, shielding the Salmon’s daughter, 15-year-old Jennifer, when a second set of thieves burst in at 2:30 the next morning and, angry because they couldn’t find any pot, started shooting.

“I know who committed the murder,” Lutz assured Curry. “It is a different group of people than you have in custody for the crime. You have the wrong guys.”

The worst feeling a prosecutor can have is to know in his bones who committed a serious crime without being able to prove it in court. Second on the list is a phone call like this one.

Snitches, inmates — all kinds of people call a DA’s office with tips and information they want to pass on, usually in exchange for some kind of favor or break in their own case. Even though Lutz had been useful in the past, it was only because he wanted to save his own skin. Curry was skeptical, but he figured what the hell. The vast majority of these calls never pan out. He had nothing to lose from Lutz coming in to tell him what he knew.

It was now the middle of January 2000. On Feb. 4, Quindt was scheduled to be back in court for formal sentencing. First degree murder committed in the act of robbery could have brought the death penalty but the DA’s office elected to seek life without parole because Quindt had a very minor record, only a few juvenile offenses. He’d been in custody 14 months and in a matter of days he would be sentenced to one of the state’s toughest maximum security prisons, the ones where they send lifers with no hope of ever getting out.

“I knew if I went there I’d have to start killing people to stay alive,” Quindt said in a recent interview. “That’s the only way you can survive in one of those places. I was terrified.”

After talking to Lutz on the phone and checking out a few of the things he said, Curry asked that sentencing be put off a few weeks while he could assign an investigator to check his allegations more deeply. Lutz came into the office for the first time on Feb. 22, 2000, more than two months after a jury found Quindt guilty. He made it clear he was interested in the reward, but he didn’t want to share all that he knew right off. He was coy, Curry said, claiming he knew some of the names of those involved but not others. He was nervous, too. He wanted to make sure he wasn’t being taped and at one point, Curry and his investigator moved him into an empty office to reassure him they didn’t have a secret camera set up. Lutz said he’d come back with more details if Curry agreed to help him get out from under several arrest warrants from unpaid traffic tickets and to get his driver’s license reinstated.

Lutz had one more request. He wanted Curry to help him get into the sheriff’s academy. It was time to go straight, he said. He wanted to become a cop.

Curry said if Lutz’s information checked out, he’d give him $1,000 as a good-faith gesture and put in a plug for him on the full reward. He also would dismiss the warrants and tickets and get his license back. As for the sheriff’s academy, Lutz was on his own. Curry told him his past convictions of auto theft would probably get in the way.

But in a series of meetings over the next several weeks with Curry and Shawn Loehr, a district attorney homicide investigator, Lutz helped the DA put together a compelling case against a whole new set of murder defendants. With the approval of Quindt’s lawyer, Curry got sentencing postponed four more times. It had been one of the most heavily publicized cases of the year, but no one in the news media asked about the repeated delays. Curry and Loehr used the time to do some police work.

Lutz said a good friend of his by the name of Kelso Vidal, who had recently moved to Santa Barbara, knew one of the men who robbed the Salmon home on the afternoon of Oct. 5, 1998. Several thieves broke down the front door in the middle of the afternoon, yelling they were police. When Danny Jr., tried to stop them, he was hit in the head with a baseball bat.

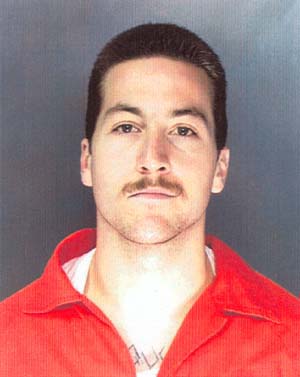

Ron Werth

Werth’s ex-wife says she knew for more than a year that Werth was involved in the crime but didn’t tell anyone because she didn’t want to destroy her brother, who she also suspected.

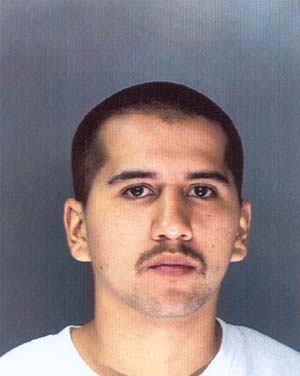

John Fjelstad

According to David Trujillo and another accomplice, Fjelstad entered the house to help steal the pot but was armed with only a flashlight.

David Trujillo

Police never heard his name during their long investigation of the home invasion and murder, but David Trujillo later confessed he was in the house and fired his gun at Riley Haeling and Jennifer Salmon.Lutz went on to say that Vidal told him he bought some of the pot taken in the attack and was told by the guy he bought it from that plenty more was at the house. Vidal figured a second robbery would be easy because the house would probably be deserted. He called his cousin, 20-year-old Ron Werth, who had spent time in the California Youth Authority for possession of illegal firearms, and, according to Curry’s informant, they made plans for a second robbery. Werth allegedly enlisted the help of two more men, David Trujillo, his brother-in-law, and John Fjelstad, a friend of Trujillo’s.

At one point in the DA’s investigation, Loehr set up a taping device on Lutz’s home phone. He was to call Vidal and see if he would repeat what he knew about the murder. The call went great, Lutz told Loehr a few days later. Vidal went into intricate detail about what happened. There was only one problem: the recording jack was accidentally pulled partway from its plug and only Lutz’s voice could be heard on the tape.

The real break in Curry’s new case came when he asked Loehr to bring in Lupe Trujillo, who is Trujillo’s sister and Werth’s wife. She initially denied knowing anything about the case, but when she was told she could be charged with accessory to murder, she hired a lawyer and consented to a second interview with Curry and Loehr.

As soon as she sat down, she began to sob uncontrollably.

“Who wants to believe this?” Lupe asked Curry, who offered not to prosecute her if she cooperated. “Who wants to live with it everyday? But I had to come forward. I can’t live with it anymore. It won’t be easy to testify and look at them, but I can’t be responsible for someone spending their life in prison because I kept my mouth shut.”

Lupe, who managed a family restaurant near the South Sacramento apartment where she lived with her five-year-old son, Reuben, told Curry and Loehr that on the morning of the murder, her husband, her brother and Fjelstadt showed up at her apartment and were clearly agitated. When she asked what was going on, Werth, her husband, barked that she should mind her own business. When she persisted, he told her to watch the news later that day and she’d know. When she saw television reports of Haeling’s death, she knew her brother and husband were responsible. Werth later told her everything. Still, she said nothing for more than a year.

Lupe withdrew from family and friends. She started drinking heavily. She gained 40 pounds. A practicing Catholic, she was beside herself with guilt. She knew it was wrong to keep quiet while an innocent man sat in jail. But if she talked, she could destroy her brother, who had a small daughter that he doted on. By this time, she and Werth were on the outs and she later said he physically and verbally abused her. She was scared what he would do to her and her little boy if he knew she snitched.

If Curry had not received his call from the informant, Lupe conceded, she might still be holding on to the truth.

“I stopped going to church. I stopped praying because I didn’t think a person like me who knew this and didn’t do anything was worth asking for anything from God.”

During the time she kept quiet, she watched all the newscasts. She saw that Quindt had a little daughter about the same age as Lupe’s son. She read that he protested his innocence, tried to escape and tried to commit suicide. Still, she said nothing until the call from the district attorney’s office.

Soon after she shared her story, Lupe found out where Haeling was buried and went to his grave.

“I bought a card and some flowers,” she said with tears streaming down her face, “and I sat there for 45 minutes and begged him to forgive me. Because I thought by me keeping this inside he wasn’t allowed to rest in peace, that his family wasn’t allowed to have peace.

“They had a picture of him on the stone and all I could remember was him just staring at me. And I wrote on the card: ‘To the family of Riley Haeling. I hope someday you can find it in your hearts to forgive me for what I did.’”

A few days after Lupe’s interview, Werth, who by this time was in a youth corrections facility on a gun charge, was due out on parole. Lupe told Curry she was terrified and wanted to get out of town. Curry did send her to stay with relatives for awhile in Southern California but he also told her not to worry. Instead of being released in a few days, Werth would be charged with murder and kept locked up. If Lupe testified, he might stay locked up for life.

Four new young men and their families were suddenly looking at the prospect of life sentences for a murder people in the community had long since forgotten.

Riley Haeling’s family had to come to grips with the idea that new men were the killers, not the ones they saw in court everyday for a month.

And Sacramento County District Attorney Jan Scully and her top lieutenants had to notify the press and stand before the community to admit they made one of the most serious mistakes a DA can make: they convicted a man of first degree murder who had nothing to do with the crime.

Amazingly enough, the four men Lutz gave up to Curry and Loehr were names that neither sheriff’s detectives nor district attorney investigators ever heard during months of work preparing to put Quindt and Salcedo on trial.

Everyone — cops, prosecutors, the media — had focused on the wrong people.

By the time Curry called the Sacramento sheriff’s detectives who worked the original case to ask their help tracking down the real killers, they said they were already swamped with new murders and had no time to spare. According to sheriff’s department case files, the detectives got reprimanded by their superiors for not passing on Curry’s request.

“In our 40 collective years we have both been on the department,” the detectives explained in a May 25, 2000 memo to their captain, “a situation like this has never presented itself before. This is the first time we have been ordered to explain why we did not make certain our supervisors were aware of unsubstantiated leads received by an outside agency.”

So it was Curry, Loehr and their informant who did the police work that cleared Quindt and led to the real killers being arrested and charged with murder. Two of the men have already pleaded guilty to less serious charges. One of the shooters, David Trujillo, who turned 20 the day of the killing, confessed to Curry in a tearful jailhouse interview. His mother says she’s now worried he will go to prison as a snitch and be killed.

The last defendant, Ron Werth, who was married to Trujillo’s sister, has defiantly insisted his accomplices lied when they said he was at the house the night of the crime and fired his gun. Both men are scheduled to stand trial next summer on charges of first degree murder.

“We just pushed it (the door) open and walked in,” Trujillo said after Curry read him his rights. “The girl was lying on the couch sleeping and Riley was there watching TV and we was just telling ‘em, ‘Where’s it at? Where’s it at?’ And (Riley Haeling) didn’t know nothing. He didn’t know what was going on. I could tell by the way he looked, by the way he was acting that he didn’t know what was going on.”

Trujillo said Werth went to a back bedroom to see if anyone else was home and a friend of Haeling’s grabbed one of the family’s shotguns.

“That’s when I started hearing shots,” Trujillo told Curry. “I think I just heard one. Then he (Werth) said something about the guy’s dead…He shot one or two more times and that’s when everything went crazy. I shot a couple of times. I just ran out of the house.”

Haeling was hit five times by bullets from two different guns. He quickly bled to death. Jennifer was hit in the legs and once in the belly. She made a full recovery. In dramatic court testimony that riveted the jury, she said there was no doubt in her mind that David Quindt was the man who shot her and Haeling.

“It’s an interesting story about how an innocent man, just based on this circumstantial web and his own kind of stupidity and lying can get 12 jurors, beyond a reasonable doubt, to convict him of first degree murder,” Curry said.

“You can see how if this was a death penalty case, I can see how some of the jurors would vote to put him to death.”

It’s also a classic tale about the fallibility of eyewitness accounts.

“It’s about as clear a case as you can have to show the frailty of eyewitness statements,” Curry said. “Because when you boil it all down, that’s what you had. You had this victim, meek as a mouse in court and totally believable — Jennifer Salmon — say, while she was crying and barely audible, that he was the man who shot her. ‘I’ll never forget those eyes,’ she said. You sprinkle in all of Quindt’s suspicious behavior and what choice did the jury really have?”

As for Riley Haeling’s mother, as crushed as she was over the thought of sitting through another trial, she could appreciate what Curry said was the “good news” about “the real killers” finally being found.

“He called and said he had good news and bad news for me and I said to him if it’s about this case it can only be bad,” she recalled. “He said we had the wrong guy but the good news is you now have the truth about what really happened. I’m not sure all DA’s would have done all that he did. Mark Curry has more integrity than anyone in the world, as far as I am concerned.”

©2002Gary Delsohn

Gary Delsohn, a reporter with the Sacramento Bee, is examining the workings of an urban District Attorney’s office.