For years after she was raped, Laurie Williams (not her real name) had occasional nightmares that took her back to that night in August 1994 when a man broke into her apartment and threatened to kill her unless he got what he demanded.

If she fell asleep with the bedroom door closed, she woke in a panic wondering if someone was on the other side. If the door were open, she’d lie awake feeling too unprotected.

A friendly and outgoing woman of 24 when she was raped, Williams withdrew into a shell. All she did was work at her job as a credit union loan officer and go to school. She was afraid to go out at night. If she saw men who were average height and stocky, like her attacker, she’d come unhinged.

“I would have to leave and go home,” she said. “I couldn’t handle it at all.”

Over and over, she’d replay the attack in her head, imagining ways “I emerged victorious — not him.”

Though she never gave up hope her attacker would be caught, each year that the anniversary of her rape approached, she’d fall apart again. If a sexual assault made the news, she’d call the detective who worked her case to ask if the attacker had anything in common with the stranger who assaulted her and stole her peace of mind that hot summer night.

“It never leaves you,” the thin, blond-haired woman, who now teaches 4th and 5th graders at a Sacramento elementary school, said of the attack. “People talk about closure after a certain period of time but that’s not a word I ever use.”

Last August, she hit bottom. California’s six-year statute of limitations was about to run out. The “Second Story Rapist” — police believed the same man was responsible for a series of attacks over several years that involved breaking into his victims’ second-floor apartments — had never been caught.

With the statute of limitations set to expire on Aug. 24, 2000, the day was approaching when Williams’ assailant never would be punished for what he did to her.

“I started to think I would have to leave Sacramento if he was still out there,” she said in her first media interview on the subject. She asked that her real name not be used because she doesn’t want any of her young students to know what happened to her. “It was just too hard to be around knowing he hadn’t been caught.”

That’s when serendipity, persistent police work and a couple of creative and dogged prosecutors took over.

In an historic case that is likely to change the way thousands of unsolved stranger rapes are handled around the country, the turn of events also marked the end of Paul Eugene Robinson’s lucky streak.

Some background: With the statute of limitations looming, Sacramento Police Det. Peter Willover faced a decision no cop ever wants to make. Because police department evidence rooms routinely toss material that’s no longer viable, the time was coming to destroy “Second Story Rapist” material that Willover had hoped to see used in court.

From the time of the man’s first attack, the detective with 34 years on the department, kept a case binder on his desk. He made periodic calls to Williams to let her know he’d not forgotten her. He chased new leads when they trickled in.

But the reality was grim. He called the DA’s office a few days before the statute expired and asked Anne Marie Schubert, a sex assault prosecutor who was one of the district attorney’s top DNA experts, if she had any bright ideas about salvaging the old cases police believed were all tied to the same predator.

There was one thing, Schubert told the detective. A few days earlier, she read a wire service article in the Sacramento Bee that piqued her interest. It was about a prosecutor in Milwaukee, Norman Gahn. He had filed a so-called “John Doe” warrant against a suspect in three rapes that were set to sink into the sea of unsolved crimes with the approach of Wisconsin’s six-year statute of limitations.

Instead of naming a suspect and identifying him by distinct physical characteristics, his date of birth and other traditional methods, this unnamed Wisconsin suspect was identified by the DNA code he left behind during his three rapes.

The filing of a warrant stops the clock on statutes of limitation, but Milwaukee prosecutors wouldn’t know if their gambit was legal until someone was arrested and prosecuted. Their John Doe, or whatever his real name was, remained at large.

With nothing to lose, Schubert told Willover she wanted to try the same thing with the “Second Story Rapist.” She also would file John Doe charges on another series of unsolved rapes that were about to expire. The man who raped Williams violated and terrorized his victims, often covering their faces with a pillow so they couldn’t identify him.

Another John Doe she planned on charging raped his victims and beat them nearly to death. These were cases police and prosecutors hated to see simply fade away.

“I don’t think anyone ever thought about this until Norm Gahn heard it from someone else and decided to run with it,” Schubert said. “I read about it in the Bee and thought, why not try it here?”

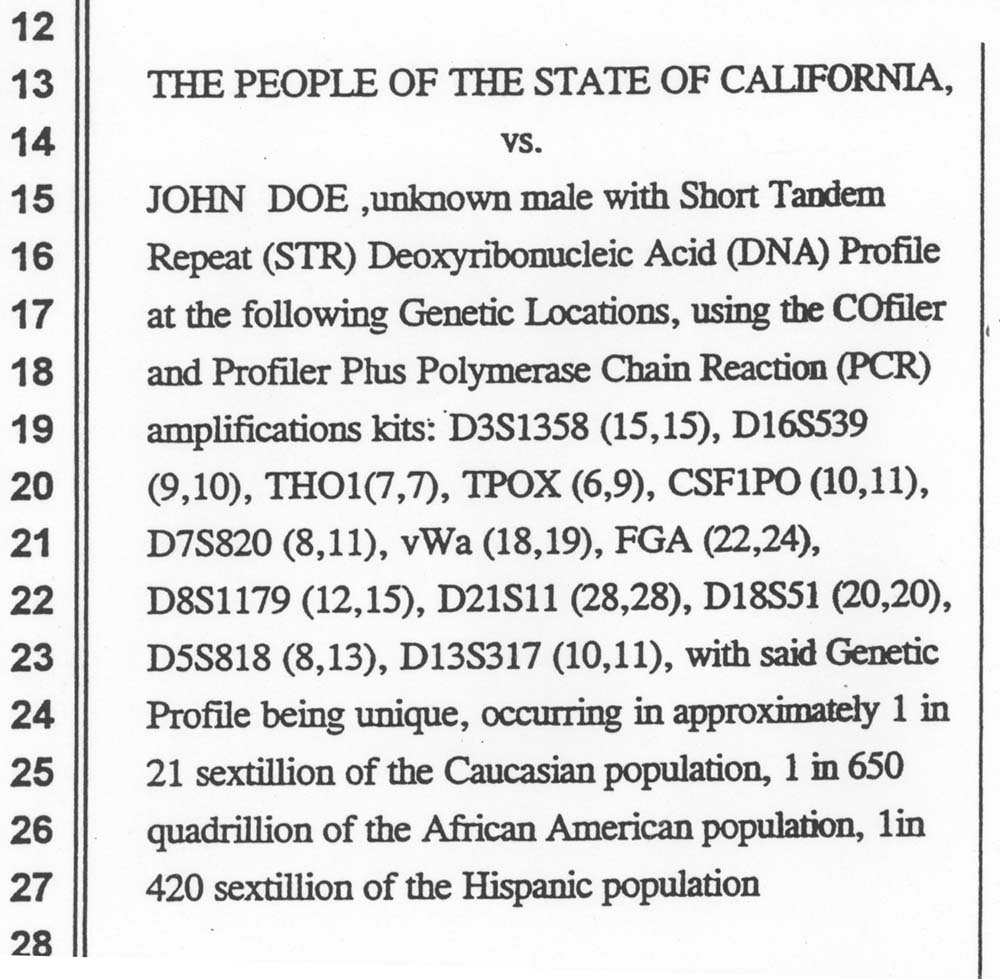

On Aug. 21, 2000 Laurie Earl, a sex assault prosecutor who now works in homicide, filed case Number 00F06871, “THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA vs. JOHN DOE.” The particulars read like something that just a few years ago would have sounded like science fiction. The charges listed the suspect as an “unknown male with Short Tandem Repeat (STR) Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) Profile at the following Genetic Locations, using the Cofiler and Profiler Plus Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) amplification kits: D3S1358 (15,15), D16S539 (9,10), THO1 (7,7), TPOX (6,9), CSF1PO (10,11), D7S820 (8,11), vWa (18,19), FGA (22,24), D8S1179 (12,15), D21S11 (28,28), D18S51 (20,20), D5S818 (8,13), D13S317 (10,11), with said Genetic Profile being unique, occurring in approximately 1 in 21 sextillion of the Caucasian population, 1 in 650 quadrillion of the African American population, 1 in 420 sextillion of the Hispanic population.”

Interesting, like the filings in Milwaukee, but meaningless unless someone was arrested.

Any cop or prosecutor will tell you, sometimes it’s better to be lucky than good. Serendipity was about to take over.

Paul Eugene Robinson, a 31-year-old ex-con, was arrested in November 1998 for violating his parole. Court records show he was free after serving part of a 64-month sentence for a string of burglaries when sheriff’s deputies say they caught him prowling and loitering around private property. Authorities now believe he was looking for his next victim, but at the time they couldn’t link him to any of the unsolved sexual assaults.

A month after his arrest, Robinson pleaded no contest to the prowling and loitering charges. He sat in the county jail awaiting return to state prison for violating his parole.

Because jailers checking his criminal history believed he had been convicted of one of the crimes listed in the state’s “DNA and Forensic Identification Data Base and Data Bank Act of 1998,” deputies took blood and saliva samples from Robinson that were then sent to the state Department of Justice Crime Lab in Berkeley.

He did have one the qualifying convictions on his rap sheet — spousal abuse — but it was a misdemeanor and state law says it must be a felony. That was mistake number one.

Sept. 15, 2000, three weeks after the John Doe warrant was filed and Robinson’s DNA profile went out to the lab, Willover got a call from a state criminalist informing him of a “cold hit.” The DNA in Robinson’s samples taken by mistake at the jail matched DNA for Robinson that was in the state’s rapidly expanding DNA database. The warrant triggered the match.

Robinson’s DNA didn’t belong in the state database for similar reasons. State law, however, allows for such mistakes when they’re made in good faith.

An amended warrant was filed listing Robinson, who again was freed after serving time for the parole violation, by name and physical description. Willover and a team of officers went to where Robinson, a cement truck driver, was living with his wife and two young sons.

His wife told the detective Robinson was at work. Willover called him at his job and told him to return home because Willover had a warrant for his arrest on an earlier traffic violation. When Robinson failed to do so, a team of warrants deputies and Willover tracked him down and arrested him later that night at a relative’s house.

His arrest meant at least two things: Laurie Williams finally could take a deep breath and stop looking over her shoulder; and the use of old DNA and a John Doe warrant would be tested in court for the first time.

“I was so excited and nervous when the detective called me I nearly fell over,” Williams said. “I had waited so long for that news. I wasn’t sure how I would react but I knew I wanted him caught and punished.”

The Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution and California law require suspects named in arrest warrants to be identified with “reasonable particularity.” So with DNA now universally accepted as the gold standard in identification, Schubert believed she was on solid ground with that part of her case.

That sea of genetic coding and information on the charges against Robinson is as particular as it gets. No two people have the same DNA. But there was another problem that threatened to sink the whole case.

California law requires the identifying information to be on the face of the warrant. But the genetic coding is so long and its use in these cases so new, computer software used to type arrest warrants doesn’t include forms that can accommodate the information.

In Robinson’s case, the warrant identified the suspect only as John Doe, “male, black.” The genetic identifiers were nowhere on the warrant. That prompted Robinson’s attorney, Johnny L. Griffin III, a former deputy district attorney, to claim in pre-trial motions that any black male in town could be arrested based on that information.

“I could have been arrested based on that description,” Griffin argued in court in March of this year. And even if the warrant were filled out properly, Griffin said it raised a much larger legal issue that never had been tested.

“Can we allow a prosecutor’s office, the DA, an office of the government, to go around that (statute of limitations) law and circumvent it to stop the clock?”

Civil libertarians and even some staunch advocates of DNA evidence have questioned the validity of extending or abolishing statutes of limitations in rapes and other violent crimes, as California and a host of other states have done or are considering. For one thing, these advocates have warned, statutes of limitations are as old as English common law and have been used to protect defendants against witness memories gone fuzzy and imprecise with the extreme passage of time.

But as Gahn in Milwaukee pointed out, he and Schubert filed John Doe warrants only in so-called stranger rapes. There are no ambiguous date-rape or consensual sex issues in their cases.

“I believe in statutes of limitations,” Gahn said. “You don’t want to have stale charges and you want to make sure memories are fresh. But DNA is different. Every one of the cases we’ve filed is a stranger dragged off the street or raped after her house was broken into.

“And when you have semen on a vaginal swab I think someone will remember dragging someone off the street and into a garage or something and inserting his penis in her. There is nothing the least bit vague about any of this.”

In December, in fact, Gahn, the original pioneer of the John Doe DNA rape warrants, got his own cold hit on one of his cases. Bobby Richard Dabney Jr., who has been in prison on a variety of robbery and other charges, was charged with five counts of first degree sexual assault for crimes committed against one victim on Dec. 7, 1994.

“In a rape case, if you have good, reliable evidence, there is no reason for these cases to ever go away,” Gahn said.

In defending her case, Schubert argued that the computer version of her John Doe warrant directed any law enforcement officer reading it to an additional set of “remarks” that did include Robinson’s full genetic coding and the admonition to contact Det. Willover.

“I don’t lose sleep over cases but I lost a lot of sleep on this case,” Schubert said. “To do something that was such a great thing and then lose it because of a potential mistake we made — I was really sweating it out.”

According to Superior Court Judge Tani G. Cantil-Sakauye, who denied Griffin’s motion to dismiss the charges because the warrant was invalid, the attack on the validity of the warrant was “hypertechnical.”

In explaining her ruling, Cantil-Sakauye said she first considered the case “straightforward and really simplistic in nature, and that is, the arrest warrant on its face lacked particularity in describing the subject John Doe.”

According to the judge, that made the warrant invalid, which meant the statute of limitations would have passed and Robinson could not be prosecuted.

But upon further reflection and study of case law, the judge said she concluded something altogether different.

“The spirit of the Fourth Amendment and the particularity requirement is met in this particular case given the information readily available,” she said in ruling from the bench after an all-day hearing on Feb. 23.

Arrest warrants are specific to protect against the wrong person being arrested, she said. Police would be directed to Robinson’s genetic coding in the “remarks” section of the paperwork and computer forms accompanying the warrant, so, she said, no one could be arrested based on the coding alone.

“There would be less of an abuse of the process of arrest in this case because no reasonable officer would arrest any male black who refused to give him his name, then call him John Doe and bring him in,” the judge said in a courtroom that included the suspect, the victim and her friends and family, as well as other lawyers wanting to witness the hearing.

As for the larger question, Cantil-Sakauye took pains to explain how legal issues raised by the defense are part of a moving and evolving target.

“Reasonable particularity means a different thing in this day and age than it did even as late as 1967,” she said.

One hundred years ago, all authorities had to identify someone was a name. Even fingerprints, she said, are not always conclusive proof of a crime, and people can alter their physical appearance with cosmetic surgery.

“But in my opinion, it certainly appears that, as of today, DNA is unalterable in the year 2001, and it appears to be the best identifier of a person that we have.

“Based on what I heard about the input of that information fields and computer systems, I don’t think we’ve caught up with that concept yet. But I would submit that is the most accurate description we have to date,” she said.

Schubert called it the most important case of her and Earl’s legal career and the two prosecutors each joked they’d be busted back down to misdemeanor duty if they failed.

Like the John Doe cases in Milwaukee, the Sacramento case drew national attention and even Gahn called the first affirmation of John Doe DNA rape cases a landmark.

“A lot of states are moving back or abolishing their statutes of limitations and that’s good,” Gahn said. “There should be no statute of limitations on rape cases with DNA evidence. And with the court in Sacramento now saying they’re valid, it will make it much easier for states to take action. It’s less of a jump for them.”

Defense attorney Griffin, meanwhile, said he would appeal the ruling all the way to the U.S. Supreme court. A California appellate court and the California Supreme court have already refused to hear his appeal. “My client maintains he is totally innocent but we have not yet even addressed the substance of the charges,” said Griffin. “There are a host of issues we can raise but right now we are simply maintaining that the warrant was invalid and I genuinely believe we will prevail on appeal.”

Lest anyone forget, however, why landmark legal rulings have the impact they do, Laurie Williams was thrilled with Judge Cantil-Sakauye’s decision and looks forward to facing Robinson again in court. She will testify against him and she hopes he is put away for the rest of his life.

“I really dreaded seeing him in court,” she said after the February hearing. “I didn’t know how I would react. My biggest fear was that he would go free. Now that I’m over that hurdle, I am fully prepared to testify against him. He broke into my apartment when I was sleeping and raped me. I don’t think they can say anything to discredit me.”

©2001 Gary Delsohn

Gary Delsohn, a reporter at the Sacramento Bee, is spending a year examining the District Attorney’s office in Sacramento.